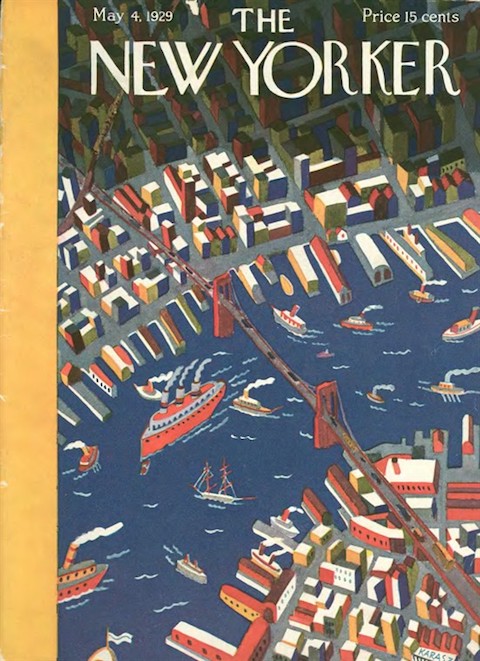

The re-opening of New York’s Central Park Casino in 1929 was in many ways the city’s last big party before the economy came crashing down, along with the exhuberance and frivolity of the Jazz Age.

The Casino itself wasn’t new–it opened in 1864 as the Ladies’ Refreshment Salon (sometimes spelled “saloon”), a two-room stone cottage designed by Calvert Vaux. As Susannah Broyles writes in her excellent blog post for the Museum of the City of New York, the Victorian cottage was a place where “unaccompanied ladies could relax during their excursions around the park and enjoy refreshments at decent prices, free of any threat to their propriety.”

Broyles writes that by the 1880s the salon had morphed into a far pricier destination, a restaurant called The Casino, open to both sexes. With the rare attraction of outdoor seating, “it was the place to see and be seen.”

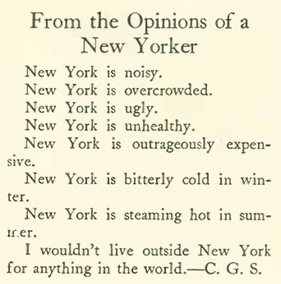

By the 1920s the restaurant had grown a bit shabby. Then along came the city’s flamboyant mayor, Jimmy Walker (1881-1946), who saw the potential of the property as a place where he could hob-nob with wealthy and fashionable New Yorkers and openly flaunt Prohibition laws. There were others, however, who found the idea of an exclusive playground for the rich in a public park distasteful. The New Yorker observed as much in the “Notes and Comment” opening of “The Talk of the Town”…

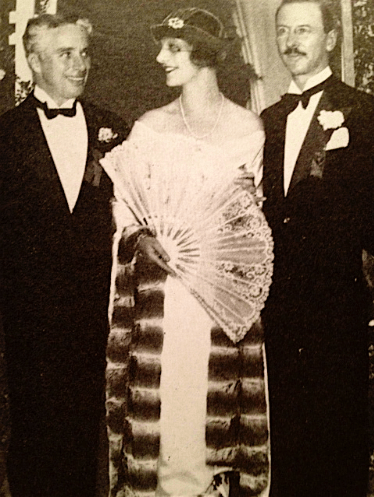

…the “Schuyler L. Parsons” referred to above was a tireless host, prominent decorator, and a society A-lister. He is pictured here (circa 1930) with two of his closest friends, actor Charlie Chaplin and the actress, singer and dancer Gertrude Lawrence…

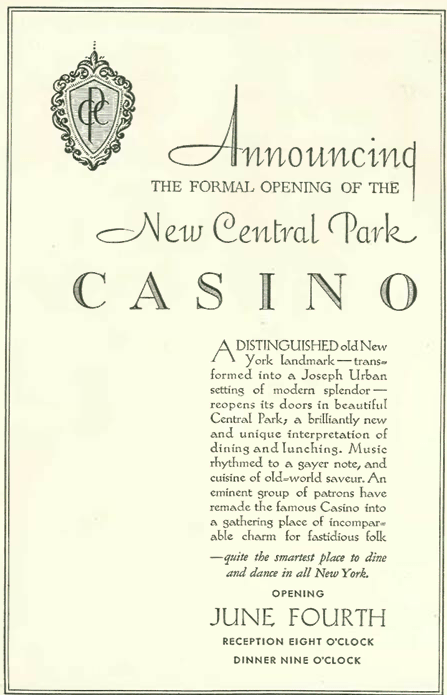

The Central Park Casino reopened its doors on June 4, 1929 at an invitation-only event. The following day it would open to the public, but as New York’s newest and most expensive restaurant it would remain closed to all but the wealthiest. As The New Yorker observed, the city was, after all, a “plutarchy,” and the populace passing by the Casino would at least be allowed “to glimpse the decadent class in the act of eating a six-dollar dinner” (nearly $90 today).

This formal announcement of the opening appeared in the May 6, 1929 issue of The New Yorker, including the time of the event—I suppose for the benefit of the 600 who actually had an invitation, or perhaps to tantalize those without such credentials…

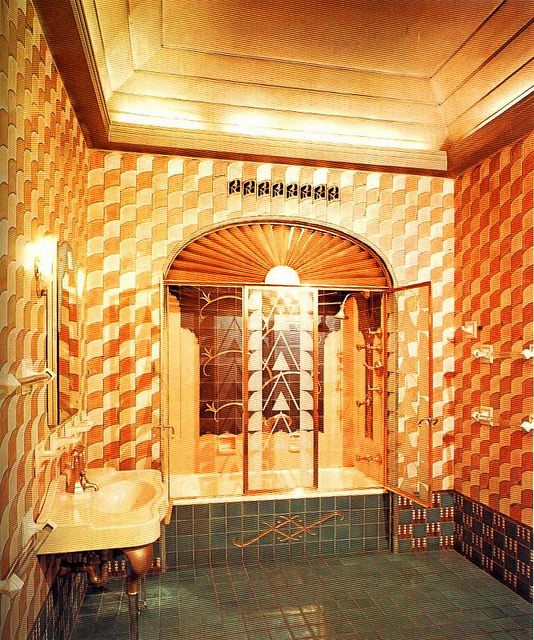

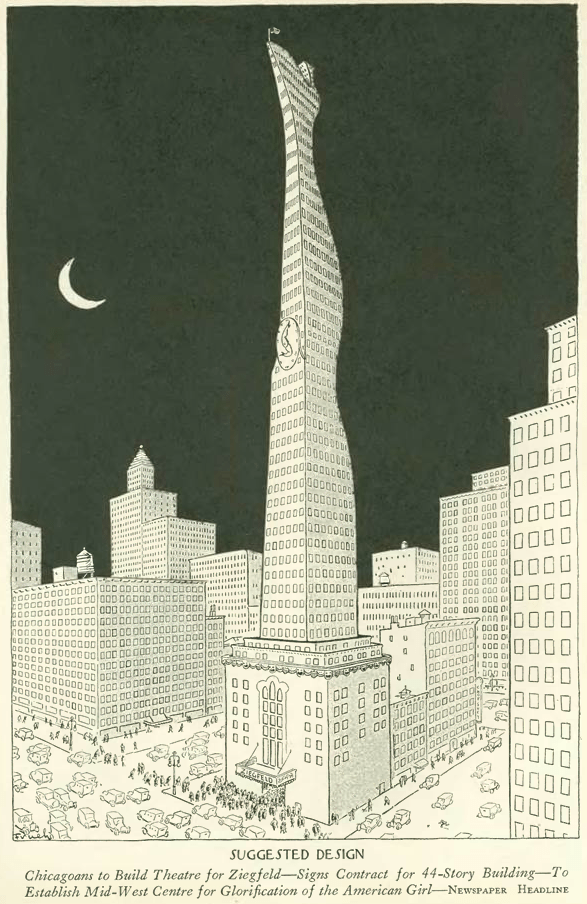

The Casino was a playground for the rich by design, conceived in the image of the flamboyant Mayor Walker—himself a product of the Tammany Hall political machine—and executed by hotelier Sidney Solomon, who obtained the building’s lease via some Tammany-style subterfuge. Solomon hired architect and theatrical set designer Joseph Urban to transform the Casino into a glittering showpiece of Jazz Age nightlife.

The New Yorker continued its observations on the Casino in another “The Talk of the Town” piece titled “Historical Note,” attributing the inspiration for the Casino not to Walker or Solomon, but to socialite Anthony Joseph Drexel Biddle Jr…

Well, as you’ve probably guessed, the party didn’t last forever. After the October 1929 stock market crash, the sight of rich folks stuffing their faces and drinking fine wines in a public park looked even more unseemly. Soon the Casino found itself in the crosshairs of Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, who detested Mayor Walker.

As for Walker himself, a growing financial scandal prompted him to resign from office on Sept. 1, 1932. He promptly fled to Europe with his mistress, Ziegfeld girl Betty Compton, and stayed overseas until the threat of criminal prosecution had passed. For Moses, it wasn’t satisfaction enough to see Walker driven from office. In 1936, despite protests from preservationists, Moses had Urban’s lovely restaurant demolished. It was replaced by a children’s playground the following year.

* * *

A Drinking Life

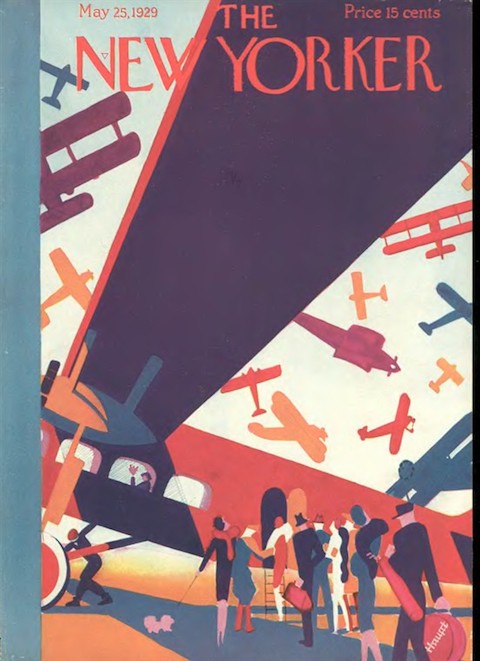

As the Jazz Age was winding down, one of its greatest chroniclers began a brief relationship with The New Yorker. In the March 12, 2017 issue of the magazine, Erin Overbey and Joshua Rothman wrote “There’s a doomed, romantic quality to the relationship between F. Scott Fitzgerald and The New Yorker; they were perfect for each other but never quite got together.” In total, Fitzgerald published just two poems and three humorous shorts for the magazine, beginning with this piece in the May 25, 1929 issue:

Fitzgerald’s last contribution to the New Yorker would appear in the Aug. 21, 1937 issue (“A Book of One’s Own”). Following the author’s death in 1940 the magazine would feature various articles on his life and work, and in 2017—77 years after Fitzgerald’s death—the New Yorker would publish a long lost short story, “The IOU.” A fitting title for an author who sadly did not get his due while he was alive.

* * *

One of the Gang

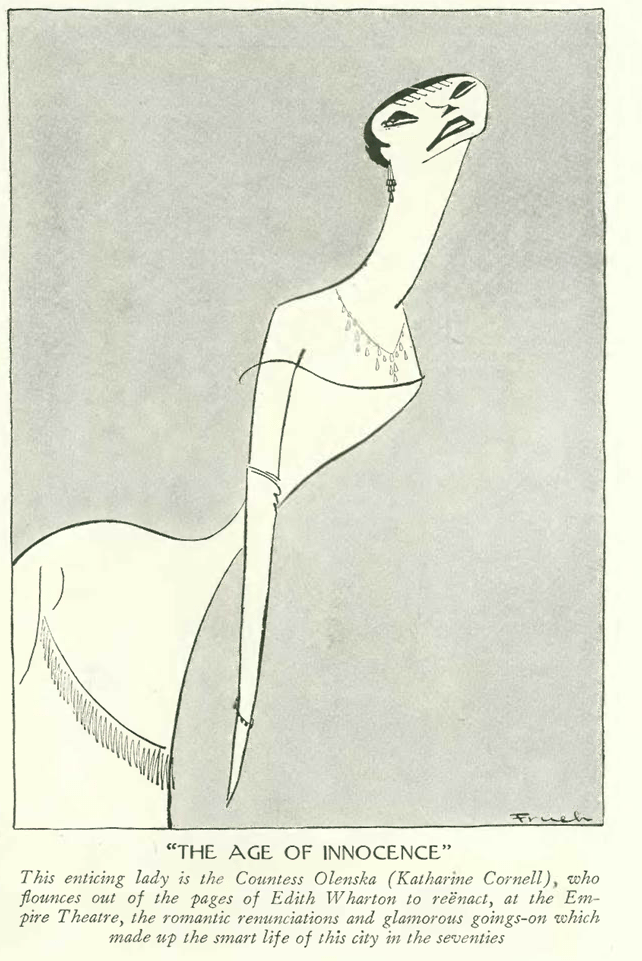

Among the Jazz Age artists and writers who orbited around the Algonquin Round Table (and the Central Park Casino) and chummed with the writers of the New Yorker was musician and composer George Gershwin (1898-1937) who was profiled in the May 25 issue by his friend and longtime New Yorker writer Samuel N. Behrman. The opening paragraph (with caricature by Al Frueh):

In the profile, Behrman observed that although Gershwin expressed a desire for privacy, he was quite capable of dashing off major works in practically any setting:

* * *

Scratching the Surface

Emily Hahn (1905-1997) was a prolific journalist and author who contributed at least 200 poems, articles and works of fiction to The New Yorker over an astonishing 68-year span—from 1928 to 1996. As the title suggests, I am merely scratching surface, and will devote a post to her in the near future. Here is her contribution to the May 25, 1929 issue:

Another frequent contributor to The New Yorker was screenwriter John Ogden Whedon (1905-1991), who offered up mostly shorts from 1928 to 1938. He is best known as a television writer for such shows as The Andy Griffith Show, The Dick Van Dyke Show and Leave It to Beaver. Whedon and his wife, Louise Carroll Angell, were parents and grandparents to a number of screenwriters, including grandson Joss Whedon, creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and writer/director of The Avengers (2012) and its sequel Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015). An excerpt of grandpa’s writing from the May 25 issue:

* * *

From Our Advertisers

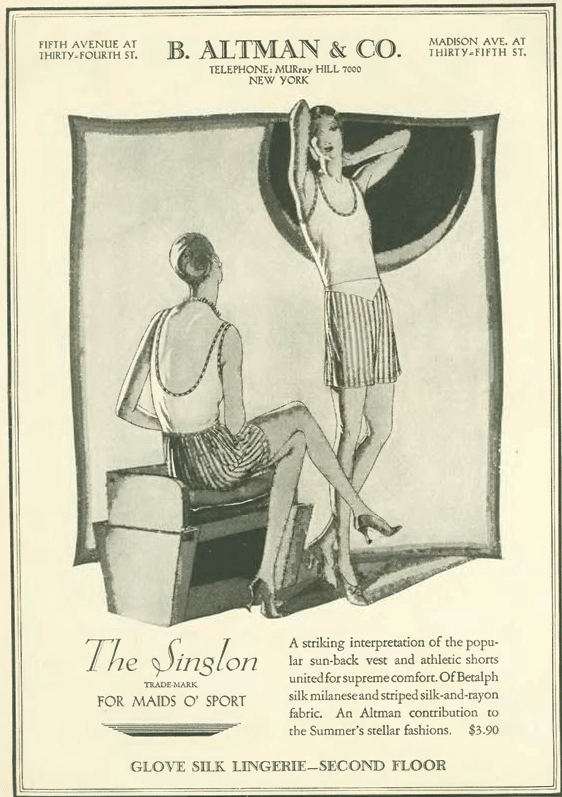

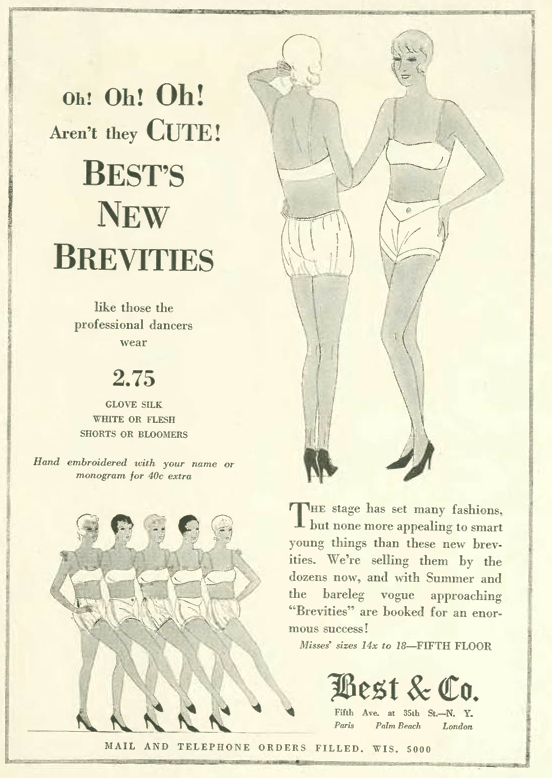

In a recent post (Waldorf’s Salad Days) I noted an ad from Lily of France that proclaimed the straight flapper figure was out, and it was now the “season of curves.” This ad from B. Altman begs to differ…

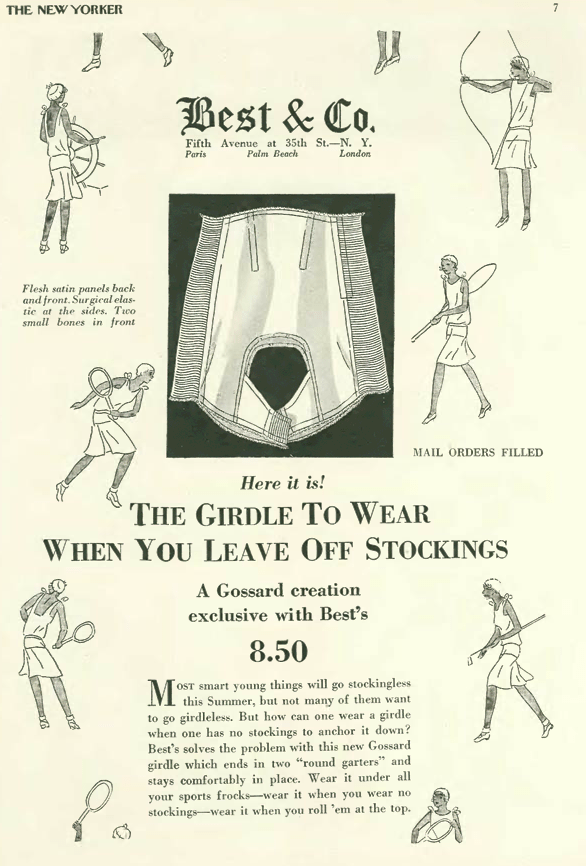

…one way to keep that straight figure was to pull on a girdle, which I’m sure felt great while one played tennis…

…our latest Lucky Strike endorser is…Mrs. Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte. Never heard of her? Well, “Mrs. Jerome” was actually a one Blanche Pierce (1872-1950) of Rochester, NY. Her second husband, Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte (the great-grandnephew of Emperor Napoleon) was something of a wastrel, having inherited a fortune and never worked at a job or profession. Blanche herself was known as a social climber…

…speaking of European nobility, here is another sad endorsement from a French noble touting the wonders of Clicquot Club ginger ale to Prohibition-strapped Americans…

…and then we have this weird “Annie Laurie” analogy used by Chrysler to sell its line of automobiles…

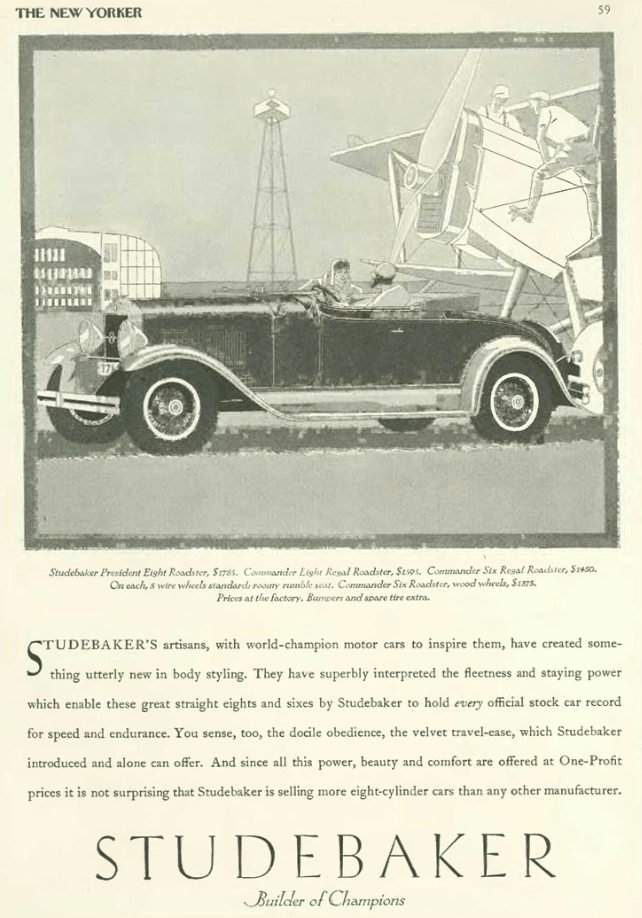

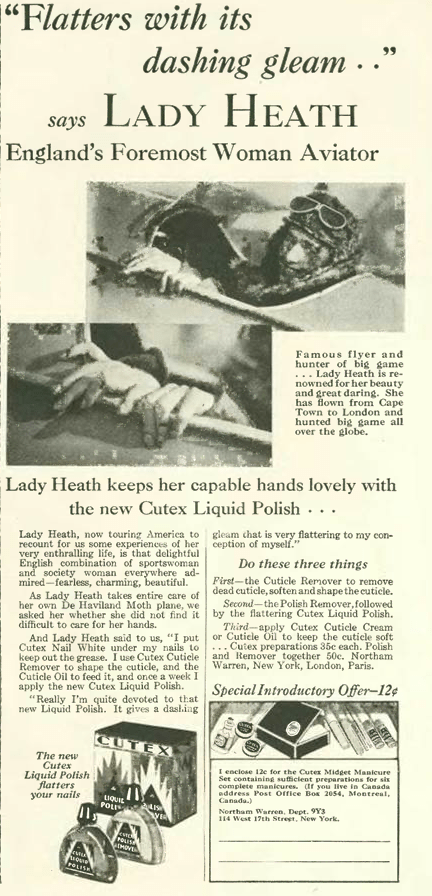

…the manufacturers of Studebaker, on the other hand, opted for a more direct approach, equating its automobiles with the speed and modernity of airplane flight…note how in both ads the cars are pictured with the windshields folded down to emphasize sleekness…

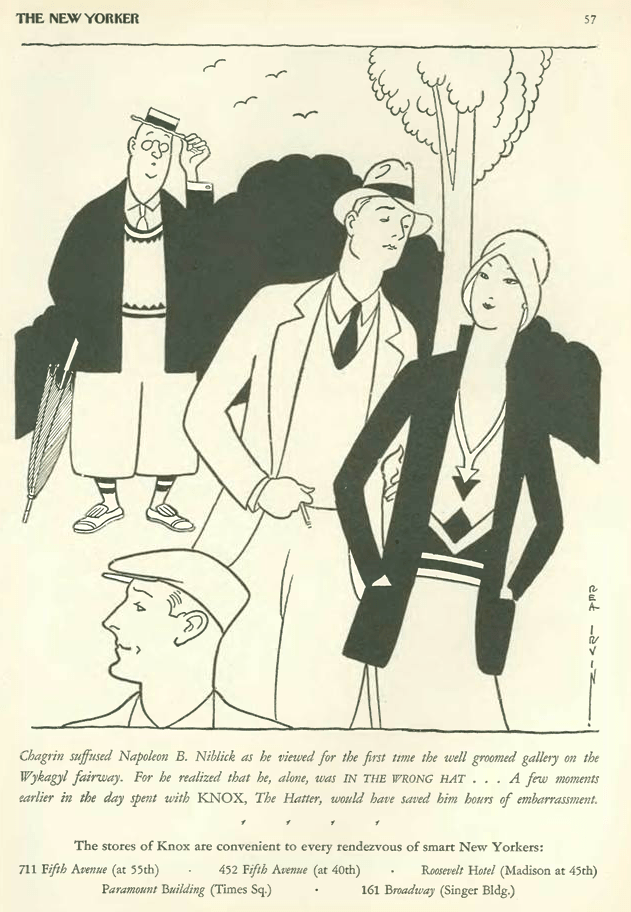

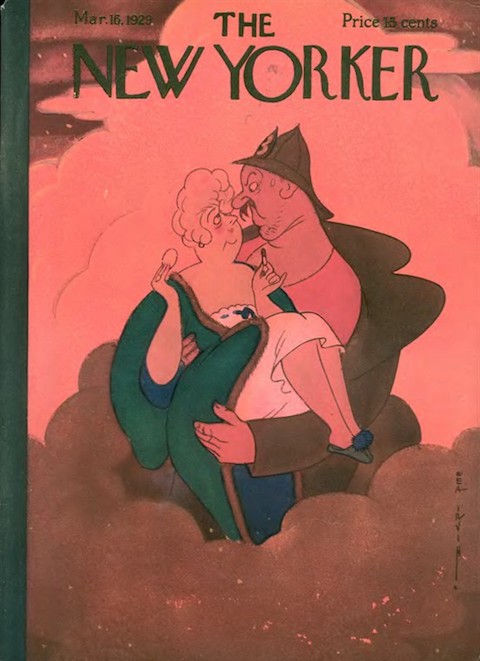

…on to the cartoons: we begin with this two-page entry by Rea Irvin, which makes very little sense…I get the part where the rich old man (stalked by his fearsome wife) finds a mistress (and a new wife) through the process of “checking his horse,” but the whole mermaid thing is lost on me…please click to enlarge—I’d love to have this one explained…

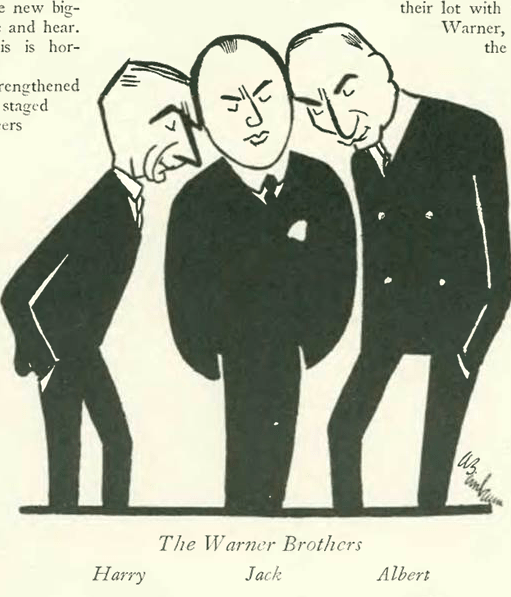

…Carl Rose had some fun with newfangled sound effects in the dawning age of the talkies…

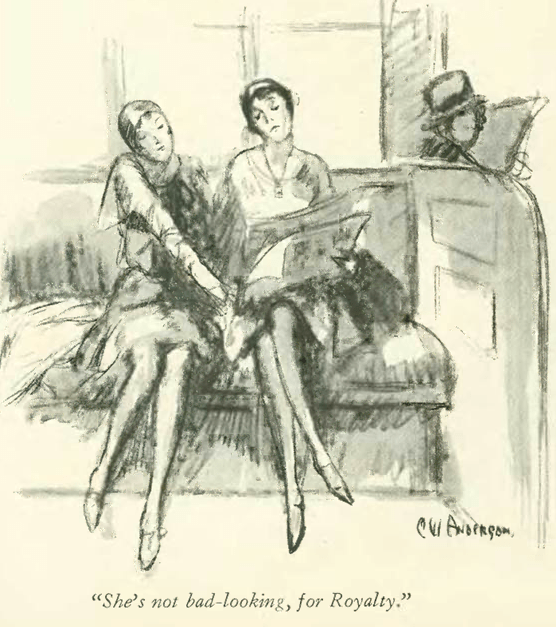

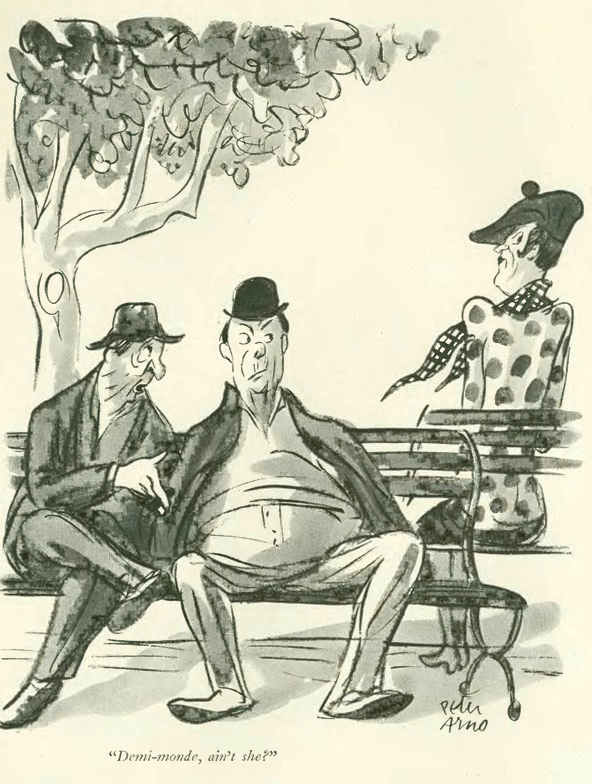

…Peter Arno sketched up the cynicism of one New York dowager…

…Perry Barlow captured two women who might have been driving home from an auction at the old Waldorf-Astoria Hotel…

…and finally, a lovely illustration by Helen Hokinson of children at play…

Next Time: The Unspeakables…