While Manhattan is home to some of the world’s most iconic buildings, it is also known for knocking them down. Sometimes it was a matter of changing tastes, but more often than not it was the steamroller of economic progress that flattened any sentimental soul that stood in its path.

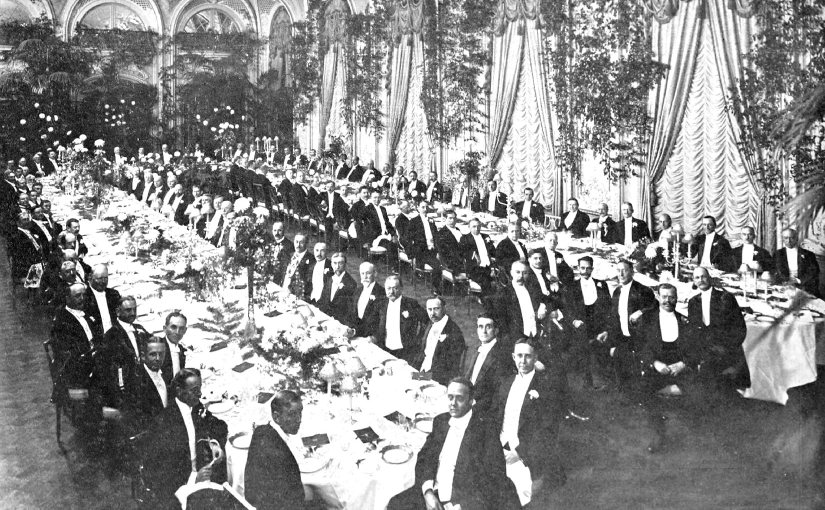

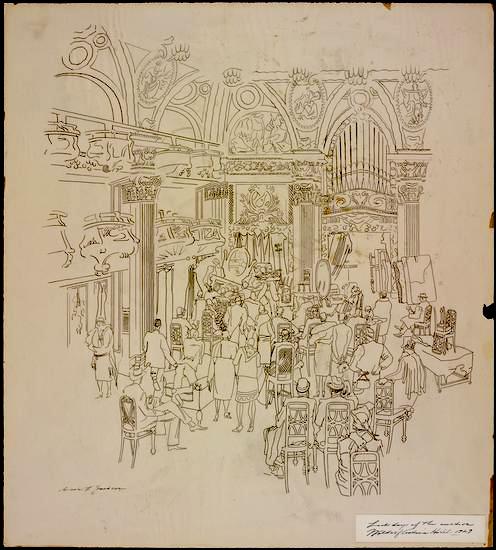

The old Waldorf-Astoria symbolized the wealth and power of the Gilded Age, but in the Roaring Twenties the storied hotel — with all its Victorian turrents, gables and other doo-dads — looked hopelessly dated despite being just a bit over 30 years old (the Waldorf opened in 1893, and the much larger Astoria rose alongside it four years later). A group of businessmen, led by former mayor Al Smith, bought the property to build the Empire State Building — an art deco edifice that would scream Jazz Age but would be completed at the start of the Great Depression. The New Yorker’s James Thurber reported on the old hotel’s last day in the May 11, 1929 “Talk of the Town”…

Thurber wrote of the hundreds of club women who mourned the loss of their familiar meeting rooms, and one elevator operator who would not be joining their chorus of sobs…

In the “Reporter at Large” column, humorist Robert Benchley supplied his own perspective on the closing of the venerable hotel, and the countless speeches that reverberated between its walls…

Benchley offered excerpts from dozens of hypothetical speeches, and then offered this final benediction to the old hotel:

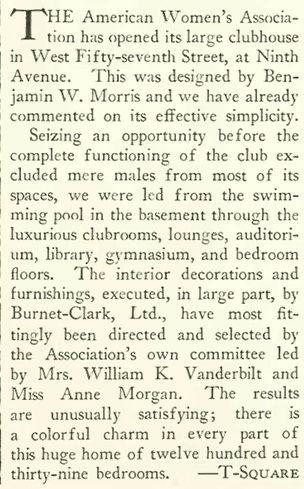

In his “The Sky Line” column, architecture critic George S. Chappell (aka T-Square) looked in on the newly completed American Woman’s Association clubhouse and residence for young women on West 58th Street. Developed by Anne Morgan, daughter of J.P. Morgan, the building contained 1,250 rooms and featured a swimming pool, restaurant, gymnasium and music rooms along with various meeting rooms.

In a 1998 New York Times “Streetscapes” feature, Christoper Gray cites a 1927 Saturday Evening Post interview with Anne Morgan, who said she believed women were at a temporary disadvantage in the business world and therefore founded the American Woman’s Association as “a training school for leadership, a mental exchange” where women “can hear what other women are doing.” After the AWA went bankrupt in 1941, the building was converted into The Henry Hudson Hotel, open to both men and women. From 1982 until 1997 the building’s second through ninth floors served as the headquarters for public television station WNET. The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour (now the PBS NewsHour) was broadcast from the building during that time.

* * *

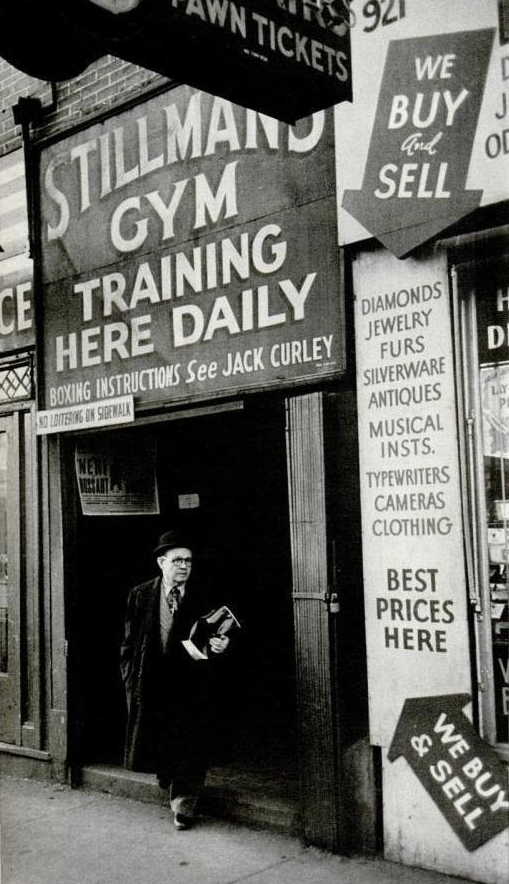

Punching for Peace

The old New Yorker was filled with personalities virtually unknown today, but who had tremendous influence in their time. Among them was Alpheus Geer (1863-1941), who founded the Marshall Stillman Movement, which promoted the sport of boxing as a way to steer young men away from a life of crime. An excerpt (with illustration by Hugo Gellert):

* * *

Before we turn to the ads, this “Out of Town” column from the back pages struck an unusual tone regarding the types of tourists planning a summer in Germany…

…and from our advertisers, this ad promoting Louis Sherry’s new “informal restaurant” at Madison and 62nd Street…

…Louis Sherry ran a famous restaurant at Fifth Avenue and 44th Street from 1898 to 1919 (like many famed restaurants, Prohibition helped put an end to it). Sherry died in 1926, so the owners of the new restaurant were merely trading on his name. In addition to a “delicacies shop” (gourmet foods were arrayed in the plate glass windows) Louis Sherry also contained a tea room, ice cream parlor and a balcony restaurant…

…like the Sherry restaurant, the new Hotel Delmonico traded on the fame of the old Delmonico’s Restaurant, which also fell victim to Prohibition by 1923. Today the hotel is best known as the place where the Beatles stayed in August 1964…

…here is another ad from Clicquot Club trying its best to sell its aged “Ginger Ale Supreme” to dry Americans. Famed avant-garde-art patron and party host Count Etienne de Beaumont (who looked like he’d had a few of something) testified how Cliquot “blends very agreeably” with the champagne most Americans cannot have…

…well, if you couldn’t have a legal drink, maybe you could entertain your friends with TICKER…”The New Wall Street Game That is Sweeping America!” My guess is this game didn’t sell so well after Black Tuesday, Oct. 29, 1929…

…those BVD’s aren’t good enough for you? Then try the “Aristocrat of fabrics” (and have a smoke while you toss the medicine ball around with the gents)…

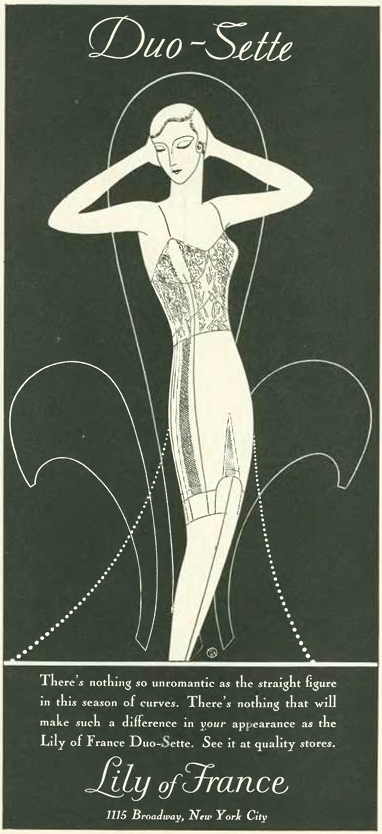

…and here is more evidence that the Roaring Twenties were losing their growl even before the big crash—the straight flapper figure was out; it was now the “season of curves”…

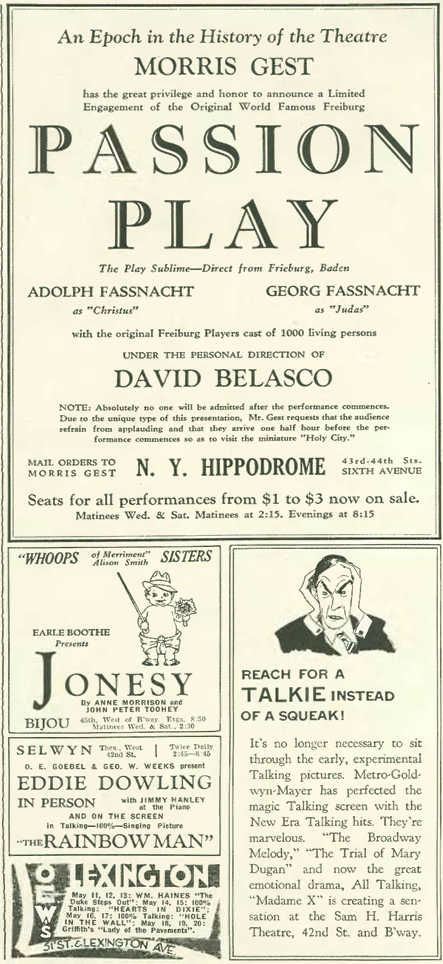

…a look at some of the cheap ads in the back of the magazine, including the one at bottom left from the Sam Harris Theater that played on the Lucky Strike cigarette slogan (“Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet!”)…

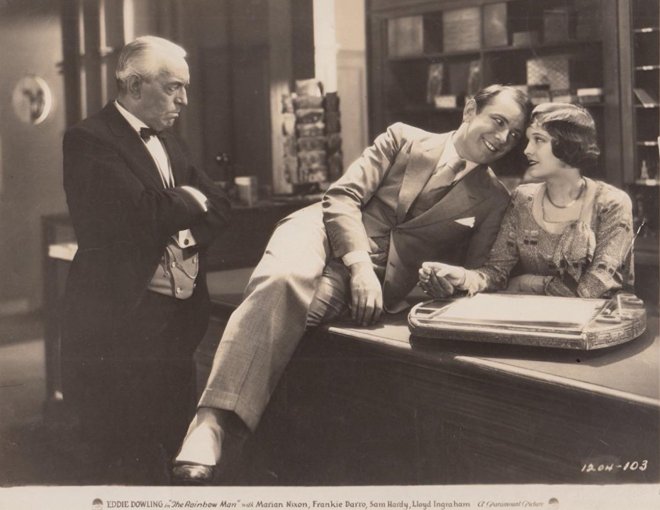

…one of the films featured at the Sam Harris Theatre was Madame X, a movie about a woman who leaves her wealthy (but cold) husband, turns to a life of crime, then tries to reclaim her son. The ad is correct in that it did create something of a sensation when it was released. It is also important to note that the film premiered at the Sam Harris for a reason: The director, Lionel Barrymore, didn’t want audiences to think his film was just another song and dance picture (like most of the first sound films) but rather a serious drama presented at a legitimate stage venue rather than a movie house…

…back to our ads, here’s a remarkably crude one from the racist misogynists who made Muriel cigars (they being Lorillard, who also manufactured Old Golds)…

…and a softer message from The Texas Company, manufacturer of Texaco “golden” motor oil…

…the artist who rendered the above couple in those golden hues was American illustrator McClelland Barclay (1891-1943). Published widely in The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Cosmopolitan, Barclay was known for war posters as well as pin-ups:

In 1940 Barclay reported for active duty in the US Navy, serving in the New York recruiting office and illustrating posters. Determined to be a front-line combat artist, he served in both the Atlantic and Pacific theatres until he was reported missing in action after his boat was torpedoed in the Solomon Islands.

* * *

Our comics are supplied by Alan Dunn, who probed the vagaries of movie magazine gossip…

…and Reginald Marsh, known for his social realistic depictions of working life in New York, including these stevedores eyeing a regatta…

…and finally, Gardner Rea looked in on a young man displaying early signs of cynicism…

Next Time…How Charles Shaw Felt About Things…