We close out November 1927 by looking at a hugely popular comic strip—Mutt & Jeff—that made cartoonist Bud Fisher both famous and wealthy.

The editors of the Nov. 26, 1927 issue of The New Yorker thought Fisher interesting enough to feature in a lengthy “Profile,” written by Kelly Coombs. A brief excerpt:

According to John Adcock’s terrific Yesterday’s Papers blog, by 1916 Bud Fisher was the highest paid cartoonist on earth. The New Yorker suggested his annual income was $300,000 (roughly equivalent to more than $4 million today). In addition to the strips, created by Fisher and a team of ghost illustrators/writers, Mutt & Jeff were featured in vaudeville engagements, theatrical shows, animated cartoons, comic books and toys.

Fisher began his career as a sports cartoonist for the San Francisco Chronicle and started his strip about “two mismatched tinhorns” in 1907. It went into syndication the following year. Mutt and Jeff, originally titled A. Mutt, is regarded as the first American newspaper cartoon published as a strip of panels, making it the first “comic strip.”

There was obviously a time when American readers thought Mutt & Jeff hilarious, but I don’t quite get its appeal. In this strip from 1926, Jeff gets a pie in the face. The giant question mark was frequently employed by Fisher, as were the dotted eye lines and explanatory arrows like the one in the last panel. No, Jeff didn’t get his brains blown out by Mutt. It is only a pie! Hah!

Another visual cliché from comics of yore was the angry wife wielding a rolling pin. Apparently Jeff refers to Mutt’s wife as an “Old Buzzard” and assumes she is already in bed (sorry about the poor quality of the reproduction). Jeff subsequently gets whacked with the rolling pin, and Mutt takes it on the bean with a flatiron. That is quite a feat, throwing a grown man through a window while simultaneously hitting him on the head with a flatiron…

The duo were also featured in more than 300 animated “half-reelers” produced between 1913 and 1926, including Mutt and Jeff: On Strike from 1920. The short film (which can be viewed here) even includes rare footage of Bud Fisher himself, since the story–sort of a film within a film–involves the penniless Mutt and Jeff going on strike after they see a movie featuring Fisher’s lavish home.

Coombs concluded the profile with these observations concerning Fisher’s personal habits:

Fisher employed a number of assistants on the strip, including George Herriman (Krazy Kat) and a high-school boy named Maurice Sendak (Where the Wild Things Are). When Fisher appeared to lose interest in the strip in the 1930s, assistant Al Smith took over and drew the strip for nearly fifty years (but Smith didn’t sign his own name on the strip until after Fisher’s death in 1954).

In Yesterday’s Papers, Adcock notes that Fisher “was the unlikeliest person you could think of to draw Mutt and Jeff…along with most of his contemporary cartoonist-journalists pals, (he) enjoyed fights, chorus girls, gambling, and saloons. Fisher liked to shoot up hotel rooms with his pistols, one of which was a gift from Pancho Villa, indoors when he was drunk.”

Heads in the Clouds

Thanks to the race to fly across the Atlantic, toy models of Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis and other planes were in high demand for the Christmas season, according to this item in the Nov. 26, 1927, “Talk of the Town:”

* * *

At a Loss For Words

Jumping back to the Nov. 19, 1927 issue, we go from the low art of Bud Fisher to the high art of John Marin featured in “The Art Galleries” section. Art critic Murdock Pemberton wrote:

But perhaps “high art” is not an accurate description of Marin’s paintings, since Marin himself wasn’t into “highfalutin words” to describe his work…

* * *

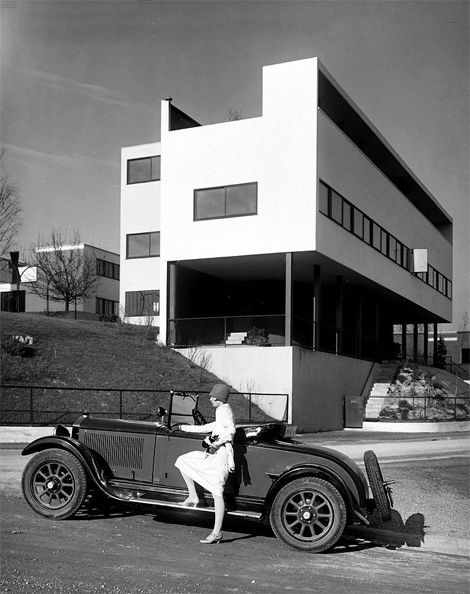

In the previous week’s issue (Nov. 12) the Marmon 8 was advertised as an ideal car for women. Not to be outdone, the folks at Buick shot back with this colorful ad in the Nov. 19 issue:

The Nov. 19 issue also featured this strange advertisement from the famed Wanamaker department store. Strange mainly because of the illustration, which features a fashionable woman departing a fanciful aircraft studded with mullioned windows(!) and a stairway that stretches to improbable depths…oh, and in case the reader might miss the snob appeal associated with French furs, the words Paris, Parisian or French are featured ten times…

And finally, the ubiquitous New Yorker cartoon featuring the humorous mismatch of rich old sugar daddy and ditzy young mistress, courtesy of Julian de Miskey…

Next Time: More Funny Business…