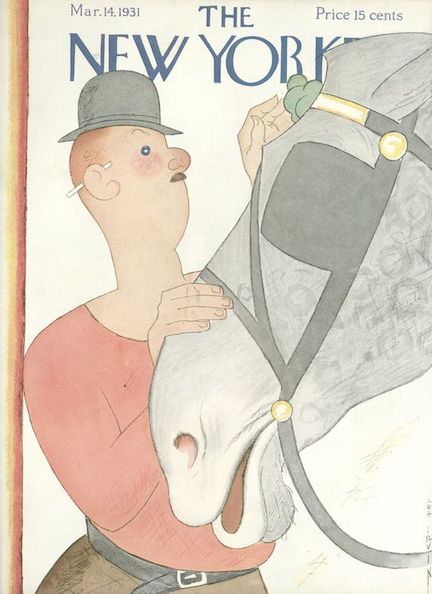

Photo above: Courtesy legendsofamerica.com

Although she served as The New Yorker’s fashion editor for decades, and even laid the groundwork for fashion criticism in general, Lois Long will always be known as one of the pivotal early writers who shaped the magazine’s voice and image.

The New Yorker’s stated mission to be both “witty and sophisticated” was fulfilled in Long’s “Tables for Two” column, in which she—perhaps more than any other writer of the Roaring Twenties—vividly captured the decadence of New York’s speakeasy nightlife. Long wrote the weekly “Tables” column from September 1925 to June 1930, when she dropped the column for a time to focus on her weekly fashion review “On and Off the Avenue” (she was also married to cartoonist Peter Arno, and they had a one-year-old daughter, Patricia, which doubtless put a cramp in her nightlife routines).

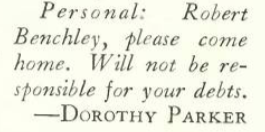

In the midst of divorcing Arno in early 1931, Long embarked on a six-part series titled “Doldrums,” lamenting the state of New York nightlife, which she found to have very little life. However, in June of that year, her divorce was almost finalized, she filed another “Tables for Two” column. Here she is, nearly a year later, with another “Tables” column, again with the familiar pen name “Lipstick,” now finding herself too old (at age 30) for the nightlife at the Pennsylvania Grill and the New Lido Club. Some excerpts:

About Buddy Rogers, Long wrote he “has a gleaming smile for the world and his-well-not-exactly wife,” a reference to famed silent film star Mary Pickford, also in the audience, and also married to actor Douglas Fairbanks (Pickford and Rogers had been carrying on a not-so-secret romance since 1927).

Long also paid a visit to the Folies Bergère, which was basically a road show produced by the famed Parisian theater of the same name. She found the performances second-rate, and didn’t quite see the appeal of the cross-dressing comedian Jean Malin, whom we’ve seen in this blog before doing his Mae West schtick.

A perusal of the 1933 Folies Bergère program suggests this was not family-friendly fare…

Long concluded her column with the familiar signature, and perhaps a sigh…

* * *

The Other Lois

We aren’t quite finished with Lois Long. I happened to notice this ad in the back pages of the issue—although the folks at Van Raalte believed fishnet stockings (first introduced in the 1920s) were all a civilized girl could desire, Long maintained a skeptical distance in her “On and Off the Avenue” fashion column:

* * *

The Brothers Mills

The “Talk of the Town” introduced readers to the Mills Brothers (Donald, Herbert, Harry and John Jr.), and if you haven’t heard of them, your parents or grandparents sure thought they were swell. Perhaps the most popular vocal group of all time, you can still hear them today, especially in old Christmas carol compilations.

* * *

Car Wars

As the Great Depression slowly crushed some of the smaller automobile manufacturers, the Big Three (Ford, GM and Chrysler) were duking it out in the advertising pages, much to the amusement of E.B. White, who filed this in his “Notes and Comment” section:

* * *

From Our Advertisers

E.B. White provides us a nice segue into our advertising section, where desperate automakers vied for the attention of cash-strapped Americans, including the makers of the luxury brand Lincoln, who hoped to convince the upper-middles that this 8-cylinder model was every bit as good as their 12-cylinder monster…

…the Lincoln Eight would still set you back a cool $2,900, roughly equivalent to a car costing $60k today…if I had a time machine I would opt for this sweet little Auburn, a bargain from a company that made some bonafide classics before the Depression plowed it under…

…Hudson would manage to hang around until the 1950s, when it merged with Nash to form American Motors, but I include this ad to remind readers that in 1932 many roads were like this, especially when you cruised beyond the city limits and headed upstate…

…the ads in The New Yorker are rife with social class cues, even unintended ones, like this illustration from Arrow shirts that suggested “old Cuthbert” was out of step with the more nattily dressed, when in fact old Cuthbert might have been old money and couldn’t have given a damn about his collar, let alone the opinions of the grasping new money crowd…

…this advertisement caught my eye initially because it was from the Theatre Guild, an organization not known to be flush with enough dough to spring for full-page spreads, but there’s more…

…John Hanrahan, who also served as The New Yorker’s policy council, became the publisher of The Stage magazine in 1932, so he likely got a break from The New Yorker’s advertising department, and deservedly so: it was Hanrahan who helped put the fledgling New Yorker on a firm financial footing during some of its toughest years.

According to Lucy Moore’s book, Anything Goes: A Biography of the Roaring Twenties (excerpt found on Erenow) “The New Yorker was ‘the outstanding flop of 1925.’ Advertisers failed to materialize. Circulation dipped below 3,000. In early May, (Harold) Ross, (Raoul) Fleishmann, Hawley Truax and the professional publisher John Hanrahan met at the Princeton Club and decided to cut their losses. The initial investment of $45,000 had gone and Fleishmann was owed another $65,000. It was costing between $5,000 and $8,000 a week to keep the magazine afloat. As they walked away from the meeting, Fleishmann overheard Hanrahan say, ‘I can’t blame Ross for calling it off, but it surely is like killing something that’s alive.’ Hanrahan’s words struck Fleishmann deeply, and when he saw Ross later that afternoon he told him that he was willing to try and raise outside capital to help The New Yorker survive.”

- As for The Stage magazine, it managed to survive the Depression, but ceased publication in 1939. Here is the final issue:

…on to our cartoonists, we begin with this nice spot illustration by James Thurber…

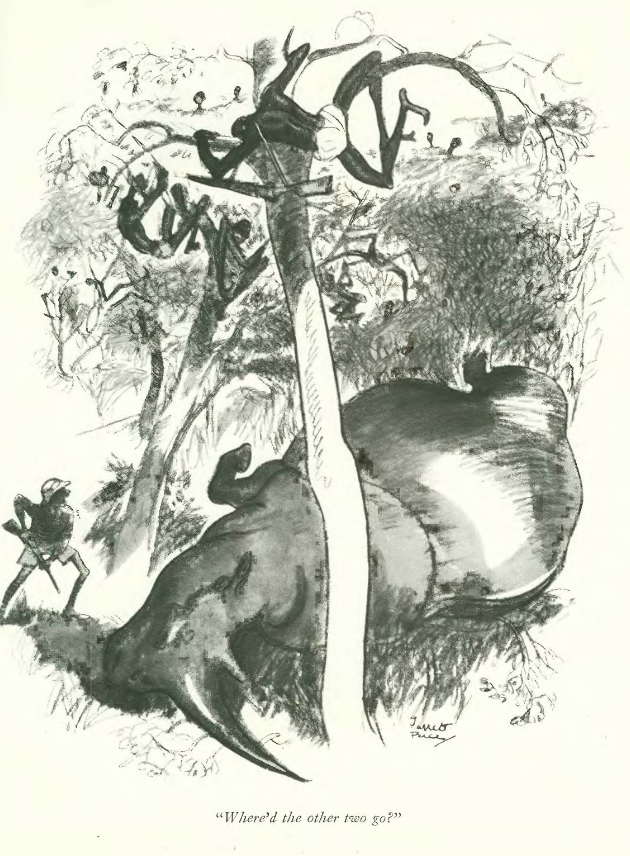

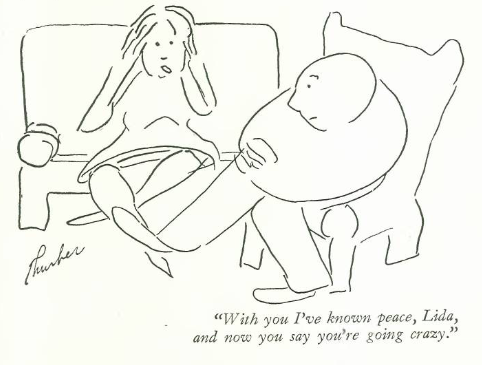

…and Thurber’s cartoon contribution to the issue…

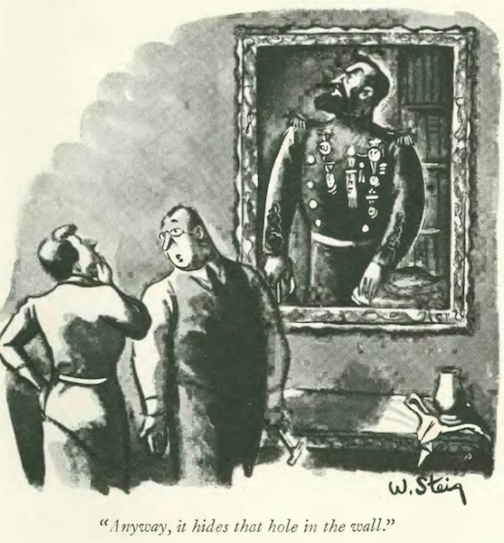

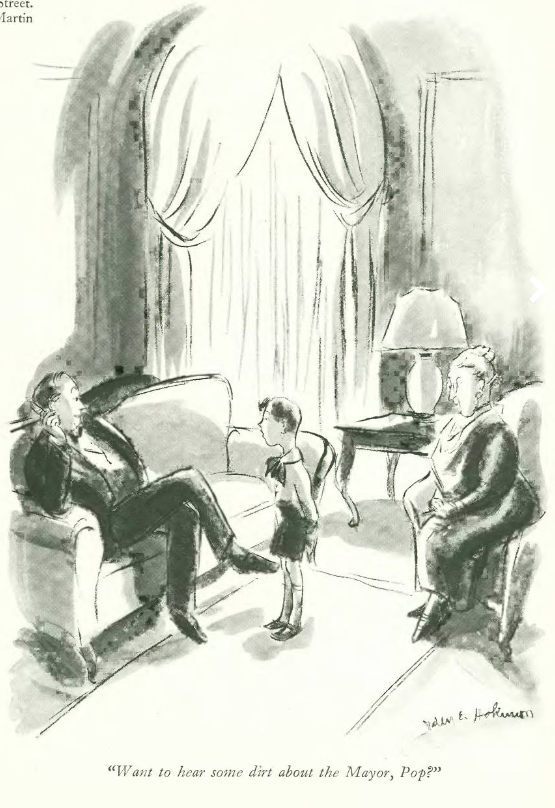

…William Steig gave us another of his “Small Fry,” coming dangerously close to being too cute for The New Yorker…

…Leonard Dove showed us some speakeasy owners appreciating an addition to the decor…

…this Otto Soglow contribution was a spot illustration, but had a lot to say about the approval ratings of President Herbert Hoover in 1932…

…those celebrated Southern manners, Mary Petty found, could be tedious in tender moments…

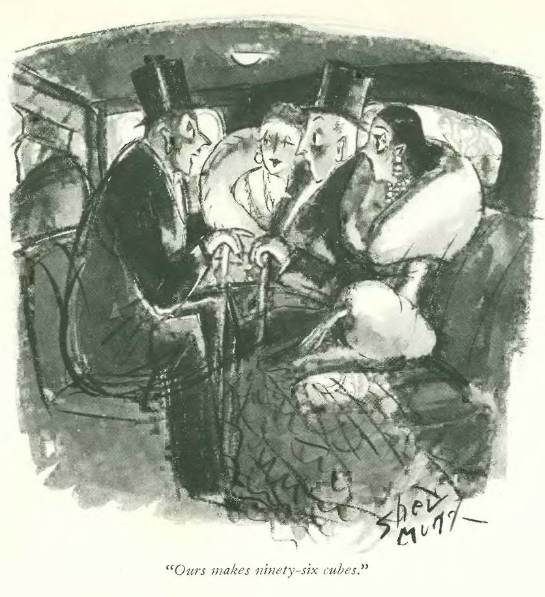

…and we close with the great Peter Arno, who gave us a peep into an awkward moment…

Next Time: The Shipping News…

dkdkd