As a book reviewer for The New Yorker, Dorothy Parker could eviscerate any writer with the tip of her pen, and often did so.

One writer, however, who received consistent praise from Parker was Ernest Hemingway, whom she first met in 1926. In the pages of the 1920s New Yorker, Parker particularly lauded Hemingway’s short story collections, In Our Time (1925) and Men Without Women (1927), which bookended his 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises (which Parker thought OK but overly hyped). When The New Yorker profiled Hemingway in the Nov. 30, 1929 issue, it naturally turned to Parker to do the honors (although Robert Benchley, a good friend of Hemingway’s, could have offered his own take on the author) :

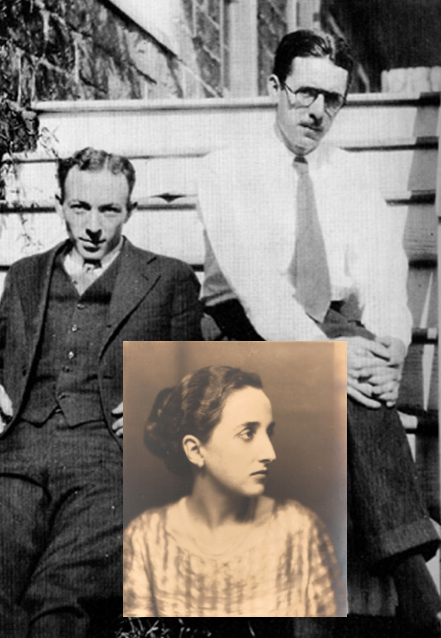

During Hemingway’s Paris years Parker actually took a boat with him to France (in 1926, along with mutual friend Robert Benchley) and so got a firsthand taste of his bohemian adventures. By the time The New Yorker profiled Hemingway, the Jazz Age was dead and Paris’s so-called “Lost Generation” was a thing of the past. Indeed, Hemingway had already been in the States for more than a year, returning in 1928 with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer.

Biographer Jeffrey Meyers notes in his book Hemingway: A Biography, that Hemingway of the early Paris years was a “tall, handsome, muscular, broad-shouldered, brown-eyed, rosy-cheeked, square-jawed, soft-voiced young man,” features that were not lost on Parker:

…more from Parker on Hemingway’s magnetic appeal…

* * *

Meet the Fokkers

In previous blogs we have established that E.B. White was an aviation enthusiast. He seems never to have missed an opportunity to catch a ride into the skies, so when pilots were conducting test flights of a prototype Fokker F-32 at New Jersey’s Teterboro field, he was there to file this brief for “The Talk of the Town”…

White’s enthusiasm for the aviation age is palpable in his description of the Fokker as it took off and climbed to a thousand feet:

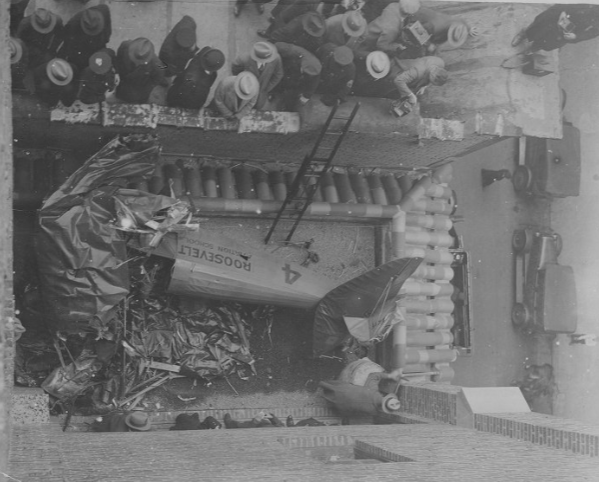

In line with The New Yorker’s stance of keeping things light, White described a scene just north of midtown, where a crowd had gathered near the site a plane crash. The pilot was killed, but a passenger managed to parachute to safety.

Speaking of crashes, the Fokker on which E.B. White was a passenger crashed a week later (Nov. 27, 1929) during a certification flight from Roosevelt Field to Teterboro Airport. No one was killed, but the aircraft was destroyed. The design itself didn’t last much longer — considered underpowered for its size, and too expensive at the dawn of the Depression, it was phased out by the end of 1930.

Perhaps after all of that flying, White needed something to calm the nerves, a subject he addressed in his “Notes and Comment” column:

* * *

The Little Gallery That Could

“Talk,” via art critic Murdock Pemberton, had more to say about the new Museum of Modern Art, that is, not taking it very seriously…

* * *

Welcome to Thurber’s World

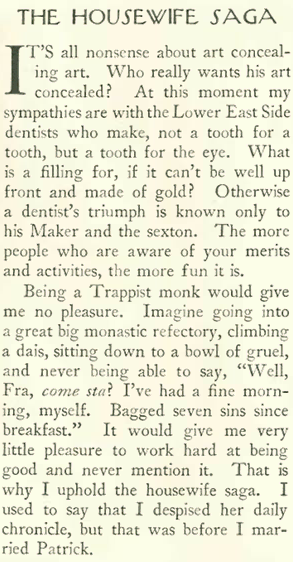

In 1931 James Thurber published his second book, The Owl in the Attic and Other Perplexities, which consisted of pieces he had done for the New Yorker, including eight stories (from Dec. 29, 1928 to Aug. 9, 1930) that featured the marital escapades of a couple in their middle thirties, the Monroes, modeled on Thurber’s real-life marriage to his wife, Althea.

The Nov. 30, 1929 issue included Thurber’s fifth installment of the Monroe saga, “Mr. Monroe Holds the Fort,” in which a fearful Mr. Monroe, left home alone (his wife was visiting her mother), imagines there are burglars in the house:

…like his famous character Walter Mitty, which Thurber would introduce in 1939, Mr. Monroe had an equally lively imagination…

The character of Mr. Monroe would see new life in the fall of 1969 when NBC debuted My World… and Welcome to It, a half-hour sitcom based on James Thurber’s stories and cartoons. The actor William Windom portrayed John Monroe, a writer and cartoonist who worked for a magazine called The Manhattanite. In the show, Monroe’s daydreams and fantasies were usually based, if sometimes loosely, on Thurber’s writings.

My World… and Welcome to It was cancelled after one season. Nevertheless, it would win two Emmys: one for Windom and another for Best Comedy Series.

* * *

Thank Heaven for Maurice

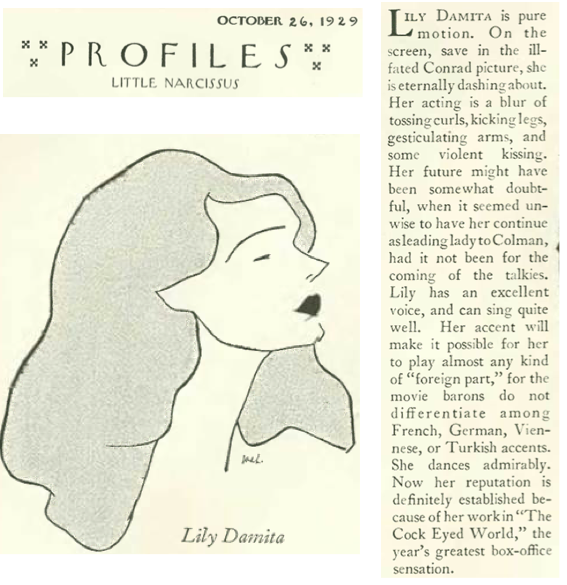

Things were looking up a bit in the talking movie department thanks to the Ernst Lubitsch-directed The Love Parade, featuring recent French import Maurice Chevalier and Jeannette MacDonald. Film critic John Mosher observed:

Mosher was much less impressed by another musical, Show of Shows, featuring an all-star cast and Technicolor that added up to little more than a “stunt”…

* * *

A Guide to Christmas Shopping, 1929

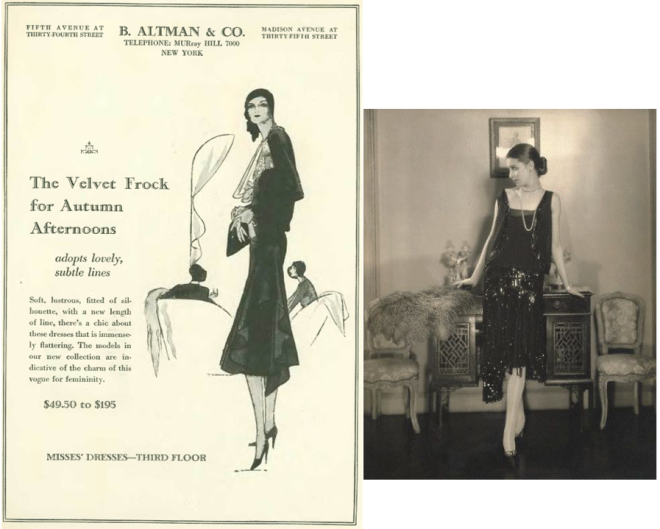

Lois Long’s fashion column, “On and Off the Avenue,” predictably grew in length as the Christmas holiday approached, and in the Nov. 30 issue she offered advice on how to go about one’s shopping duties. Some brief excerpts:

…Long’s column was peppered with holiday-themed spots, including this one by Julian DeMiskey…

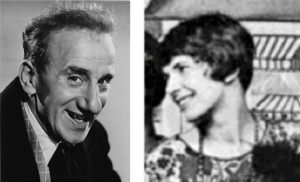

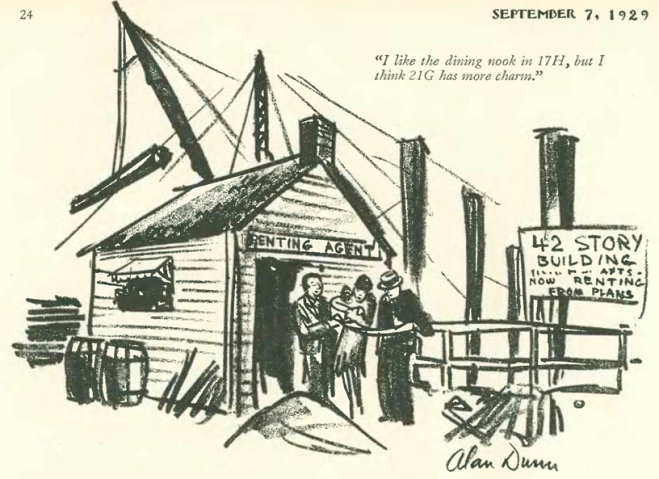

From Our Advertisers

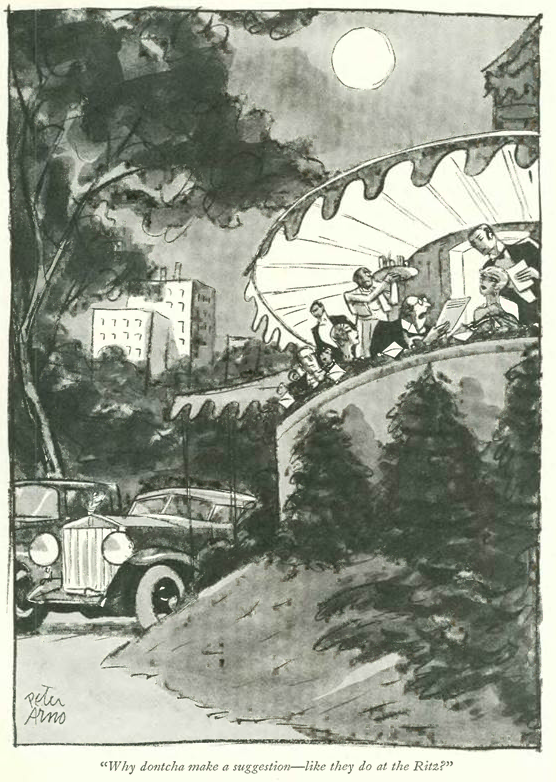

…we start with a couple of back page ads, including one from the National Winter Garden’s burlesque show and an ad announcing the imminent arrival of Peter Arno’s Parade (just $3.50, or signed by Arno himself for $25)…

…another ad hailed the arrival of The New Yorker’s second album (read more about it here at Michael Maslin’s excellent Ink Spill)…

…other ads, in full color, featured cultural appropriation by the Santa Fe railroad…

…bright silks available at the Belding Hemingway Company…

…silk stockings from Blue Moon…

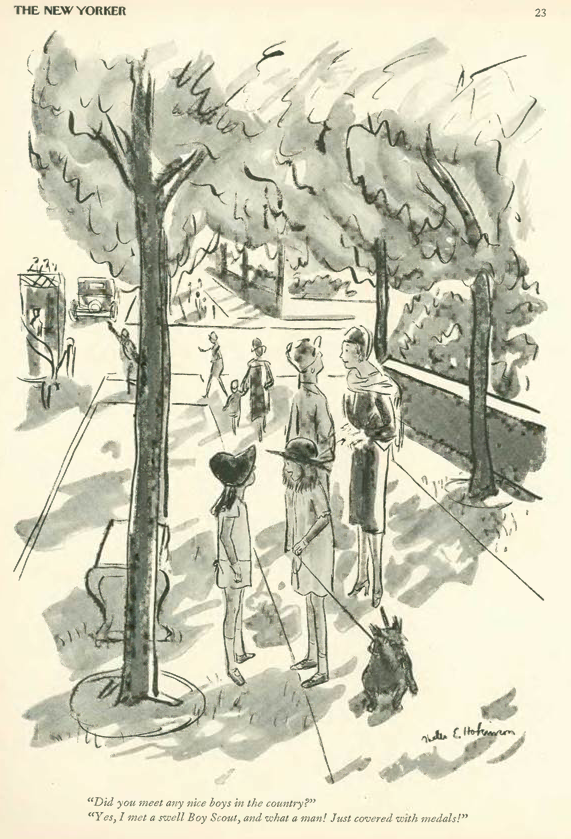

…for our cartoons, Helen Hokinson on the challenges of holiday shopping…

…Hokinson again, at tea with her ladies…

…Hokinson again, at tea with her ladies…

…Barbara Shermund, and the miracle of broadcast radio crossed with the nuances of a dinner party…

…and Shermund again, with a hapless friend of a clueless family…

Next Time: Feeling the Holiday Pinch…