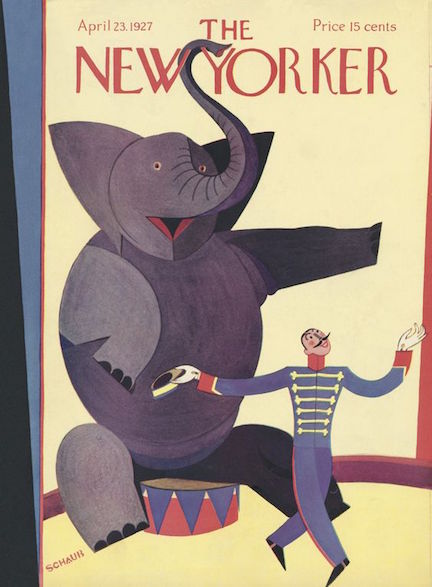

We cross the pond for the May 14, 1927 issue, for a look at all things French. As I’ve previously noted, New Yorker readers of the 1920s had a decidedly Francophile bent when it came to food, fashion and general joie de vivre.

In fact, readers were so enamored with France that the country merited its own New Yorker correspondent, Janet Flanner, who wrote under the nom de plume “Genêt.”

In the May 14 issue Flanner casually mused about the racing season at Longchamps, which attracted the likes of Anne Harriman Vanderbilt (identified here as Mrs. W. K. Vanderbilt), who was well-known in France for her philanthropic work during World War I, including her founding of an ambulance service and a hospital at Neuilly. Vanderbilt received the class of the Legion of Honor in 1919 in recognition of her war work, and in 1931 she was made an officer of the legion.

In “Talk of the Town,” the editors suggested that readers go to Madison Square Garden and check out the world’s largest canvas painting, Panthéon de la Guerre, more for the spectacle than for any artistic merit:

Panthéon de la Guerre was painted during World War I as a circular panorama—402 feet in circumference and 45 feet high—displayed in Paris in a specially built building next to the Hôtel des Invalides. It was visited by an estimated eight million people between 1918 and 1927.

The painting was acquired by American businessmen in 1927 and exported to New York, where it was displayed at Madison Square Garden. Some changes were made to the painting for the benefit of an American audience, including the addition of an African-American soldier. The work later toured the U.S.—from 1932 to 1940 it went to Washington DC, Chicago, Cleveland, and San Francisco. It was then acquired by restaurant entrepreneur William Haussner for $3,400.

In 1956 Haussner donated the work to Leroy MacMorris to be adapted for display at the Liberty Memorial in Kansas City. MacMorris drastically reduced the size of the work and modified it to emphasize America’s contribution to WWI: Only seven percent of the original work was retained, and large French sections were left out. MacMorris likened it to “whittling down a novel to Reader’s Digest condensation.” And he didn’t stop there. He also modified some figures to represent post-WWI figures such as Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman.

To reduce and reconfigure the painting, MacMorris first photographed it in detail, then cut out the figures in the photos and used them like puzzle pieces to work out his new condensed version, which was dedicated on Nov. 11, 1959.

As for the unused portions, what MacMorris did not use he threw away, sending several of the larger excised passages back to Haussner for display in his Baltimore restaurant. MacMorris also gave pieces to the art students who helped him reconfigure the painting and to a number of prominent Kansas Citians.

The National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City recently held an exhibition on the painting and its recovered fragments.

* * *

Lois Long had returned from Paris and advised readers on where to shop in the City of Light. Her fashion column, “On and Off the Avenue,” featured recommendations for many stores and bargains. It began with a brief note from “Parisite,” aka Elizabeth Hawes, who occasionally contributed to Long’s column with cables sent from Paris).

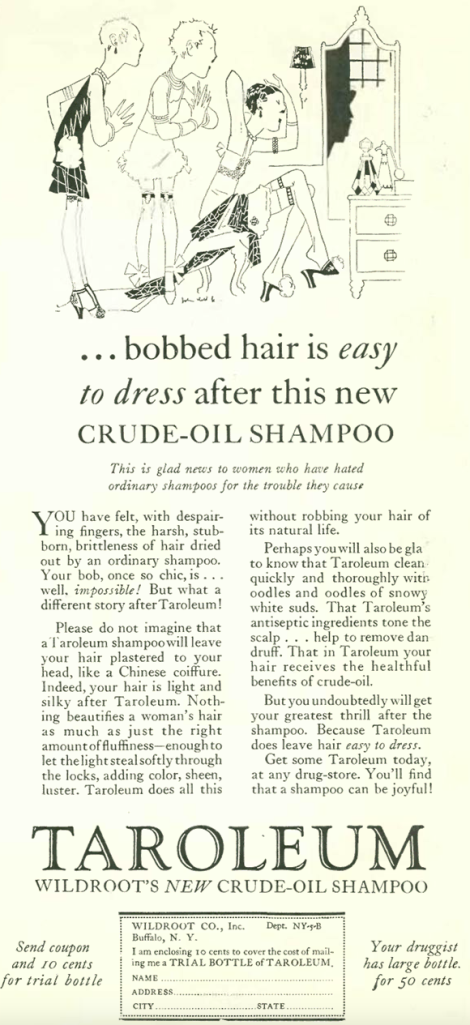

And now for the advertisements, all from the May 14 issue, featuring various French themes, such as this one for Krasny makeup that evokes the glamour of Paris and the intrigue of Russian women…

…or exotic perfumes for only the most exclusive set…

…or the chic look of Revillon Freres spring coats and wraps…

…or fake vermouth…this odd little illustration in the back pages for non-alcoholic vermouth, served by a dutiful French maid to what appears to be a giant. You have to feel sorry for the writers of such ads during Prohibition, trying so hard to make this sad libation appealing to thirsty New Yorkers…

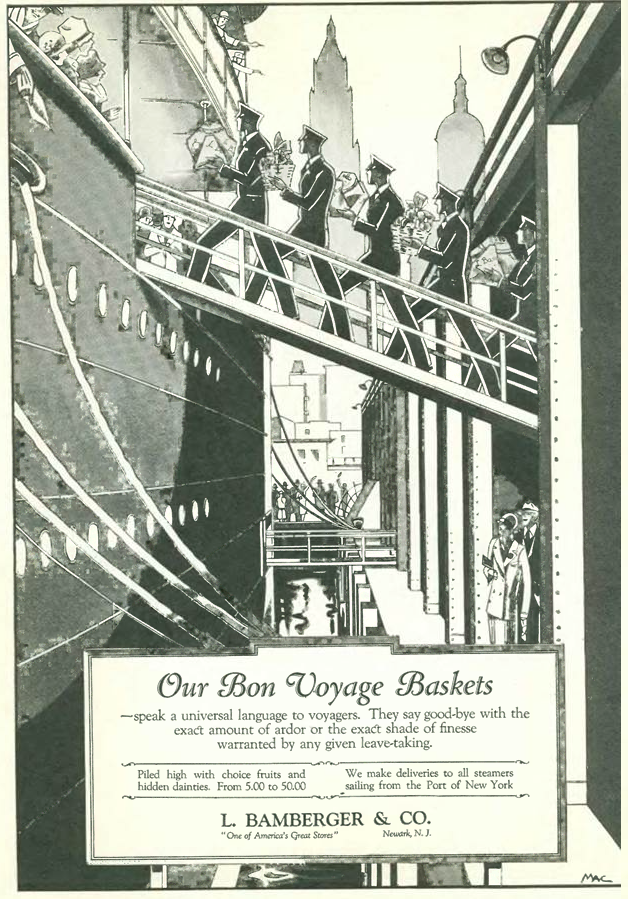

…but there were those lucky few who could actually travel to France and drink the real stuff, you could get a really swell send-off with a “Bon Voyage Basket” from L. Bamberger & Co…

…and while you were in France (at least for the men), Peter Arno could show you how to give the glad eye to the mesdemoiselles…

Next Time: Shock of the New…