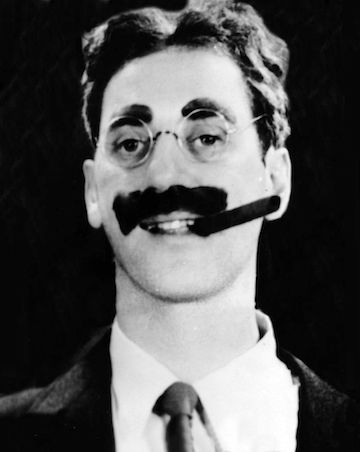

From the Upper East Side and the vaudeville stage to the shining lights of Hollywood went the Marx Brothers in 1931, starring in their first movie written especially for screen rather than adapted from one of their stage shows.

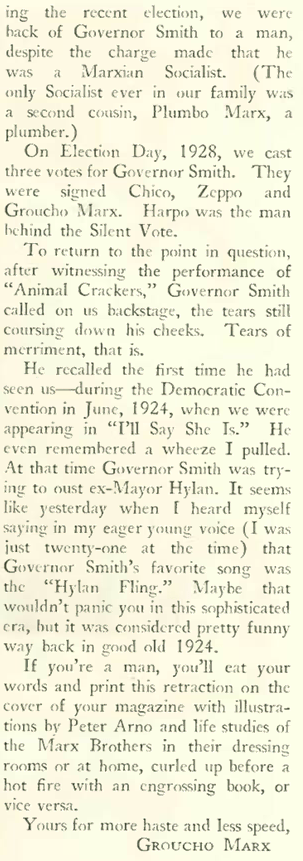

Monkey Business also their first film to be shot outside of New York. The brothers’ first two pictures—The Cocoanuts (1929) and Animal Crackers (1930)—were filmed at Paramount’s Astoria Studios in Queens. Film critic John Mosher found their latest movie to be a “particular prize” among the somewhat ordinary fare being cranked out of Hollywood. It featured the four as stowaways on an ocean liner bound for America, and that’s all you really need to know, because like most of their films it cut quickly to the chase…

Monkey Business was the first film to label the troupe the “Four Marx Brothers” (a billing that would continue through their Paramount years). A fifth brother, Gummo, left the team early and went on to launch a successful raincoat business.

* * *

Monkey’s Uncles

There was a New Yorker connection to Monkey Business — S. J. Perelman‚ a frequent contributor of humorous shorts to the magazine, was one of the screenwriters for the film. And it just so happens that one of Perelman’s shorts was in the Oct. 17 issue, and it was a doozy…

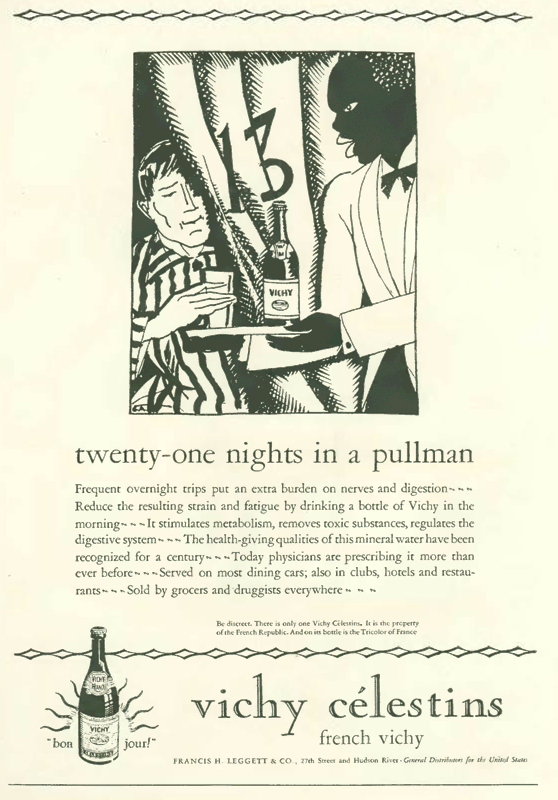

…White then moved on the subject of matrimony and advice columns, zeroing in on Dorothy Dix, the most widely read woman journalist of her time with an estimated 60 million readers turning daily to her syndicated column…

* * *

So Much for Prognosticators

The New Yorker ran an amusing two-page spread that contained the quotes of prominent writers, politicians, businessmen and economists—month by month since the October 1929 market crash—who predicted a swift end to the Depression and better times just around the corner. An except below (note the reprise of Otto Soglow’s manhole cartoon).

* * *

It Pays to be Funny

Richard Lockridge (1898–1982) was a reporter for The New York Sun when he began submitting comic sketches to The New Yorker such the one excerpted below. Later sketches would include the characters Mr. and Mrs. North. In the late 1930s Lockridge would collaborate with his wife, Frances Louise Davis, on a detective novel, combining her plot with his Mr. and Mrs. North characters to launch a series of 26 novels that would be adapted for stage, film, radio and television.

* * *

Land Barge

The “Motors” column featured the latest luxury offering from Germany, the massive 12-cylinder Maybach Zeppelin, which would set you back a cool $12,800 in 1931 (roughly $200,000 in today’s currency). Named for the company’s production of Zeppelin engines in the World War I era, the car weighed 6,600 pounds (3,000 kg).

* * *

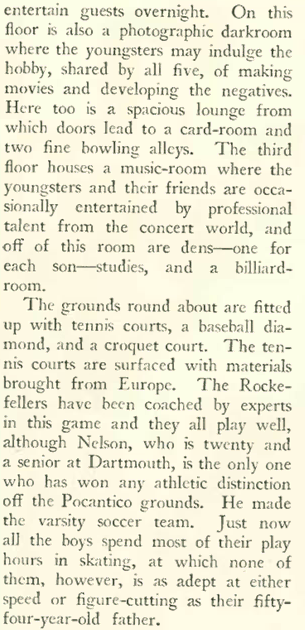

From Our Advertisers

The new Chevrolet Six was no Maybach, but the folks at GM nevertheless tried to suggest it was a car for the posh set…

…when Kleenex was first introduced to American consumers in 1924 it was marketed as a tissue for removing cold cream, and wasn’t sold as a disposable handkerchief until the 1930s…

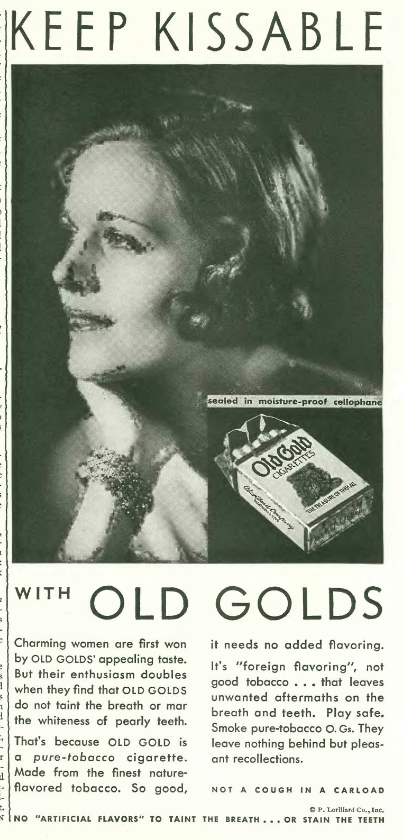

…and contrary to the wisdom of the ages, the makers of Old Gold cigarettes tried to convince us that their cigarettes would not leave smokers with bad breath or yellowed teeth…

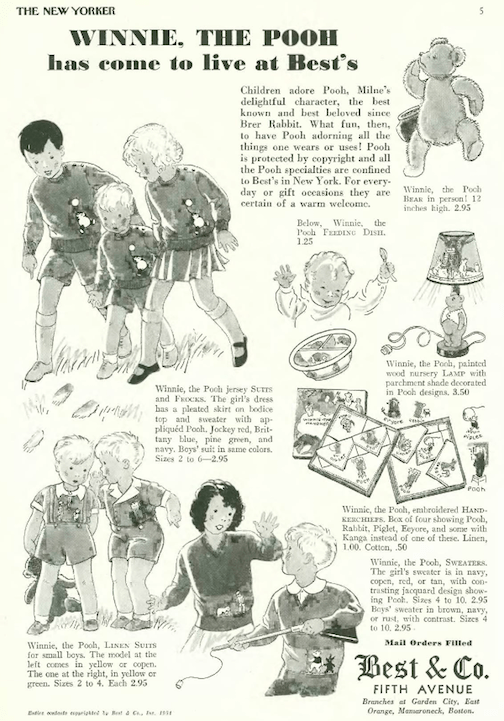

…Winnie-the-Pooh, or here referred to as “Winnie, The Pooh,” was only five years old when this ad was created for Macy’s, and even before Disney got his hands on him the bear was being turned into various consumer products including baby bowls, handkerchiefs and lamps…

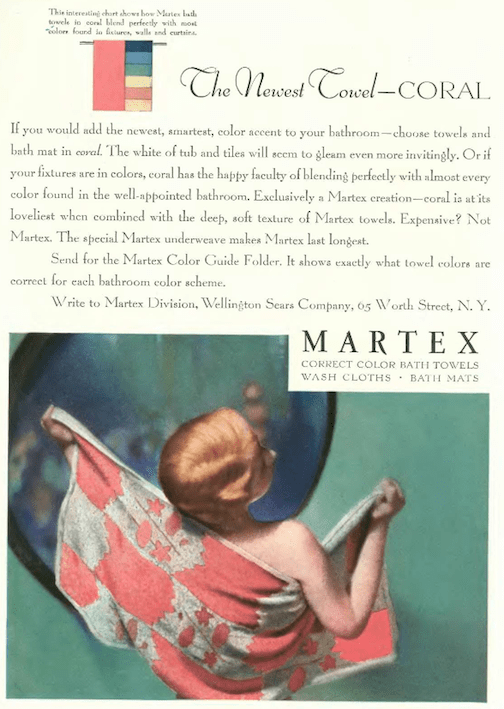

…the color ads in the early New Yorker were quite striking, such as this full-pager for Martex towels…

…or this one for Arrow shirts, featuring a determined coach making an important point to his leatherheads before the big game…

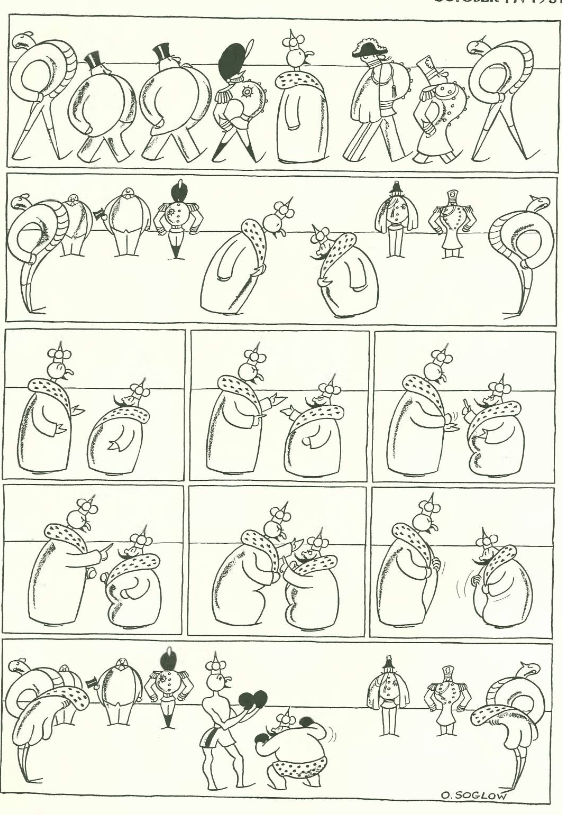

…on to our cartoons, we have Otto Soglow’s Little King engaging in some sport of his own…

…Alan Dunn showed us a meter reader who probably needed to come up for some fresh air…

…William Crawford Galbraith gave us a sugar daddy without a clue…

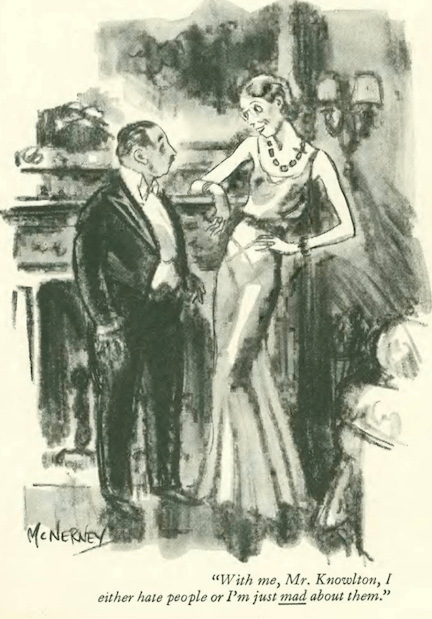

…E. McNerney showed us another pair that begged the question “what comes next?”…

…this Mary Petty cartoon recalls Carl Rose’s famous “I say its spinach” cartoon—and Mamma has every right to say “the hell with it” in this case…

…in this William Stieg entry, a father teaches his young charge the art of rubbernecking…

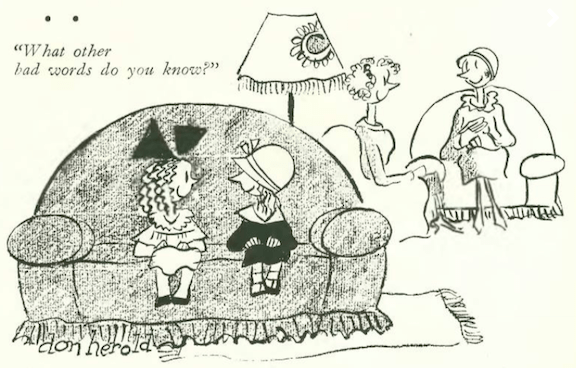

…and Don Herold gave us a peek at what the little dears really talk about while their parents exchange the latest gossip…

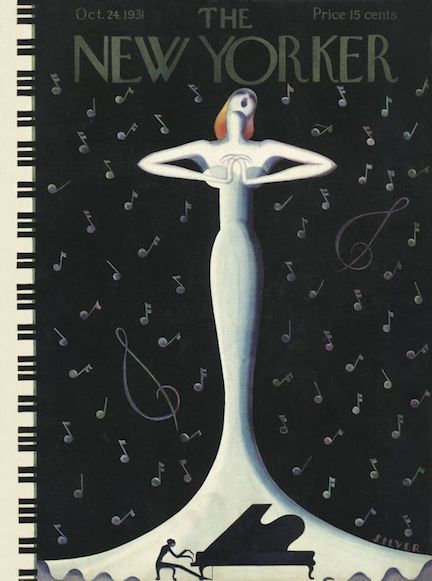

…on to the Oct. 24, 1931 issue…

…where we find the latest edition of Frank Sullivan’s satirical newspaper, The Blotz, which occupied a two-page spread (excerpt below)…

…and featured this masthead of sorts (with James Thurber art)…

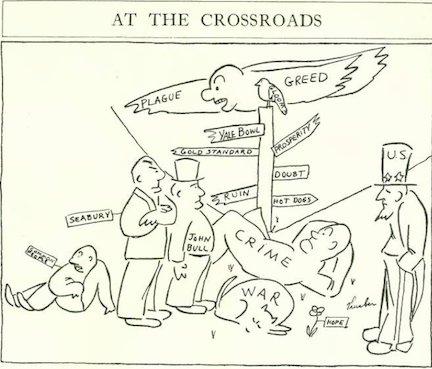

…and another Thurber contribution as The Blotz’s political cartoonist…

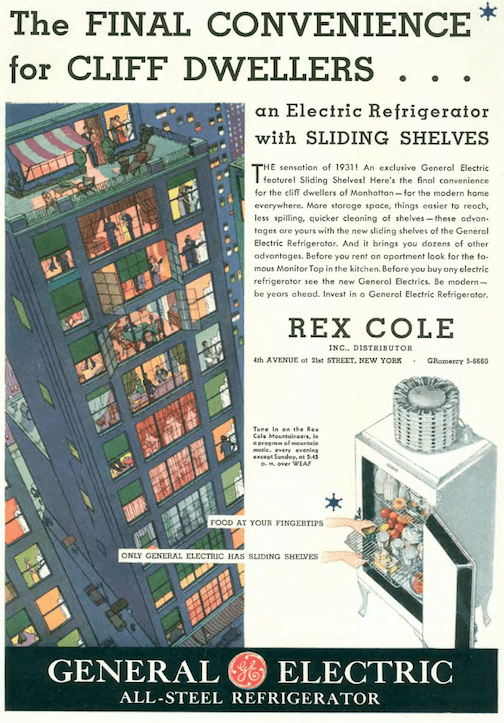

…more colorful ads to enjoy, including this nighthawk view of an apartment house…

…and this ad for Lucky Strike cigarettes, featuring 20-year-old Platinum Blonde star Jean Harlow (what is she leaning on?) who probably shouldn’t have smoked because her health was always a bit fragile—she would be dead in less than six years…

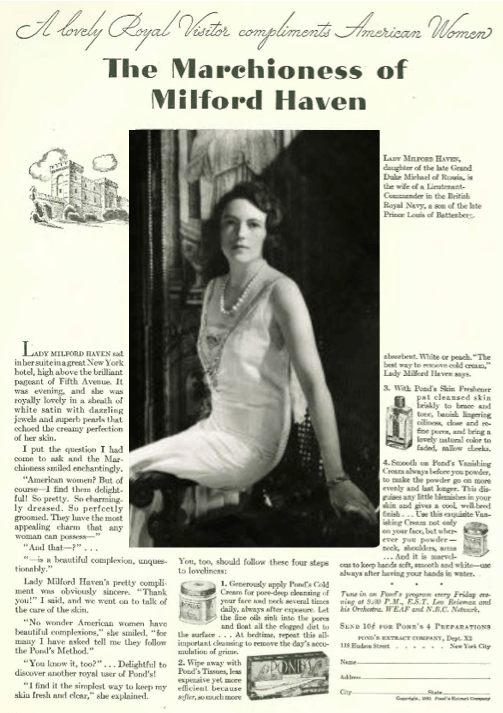

…ands then we have our latest high society shill for cold cream, Marchioness of Milford Haven, aka Nadejda Mikhailovna Mountbatten, aka Countess Nadejda de Torby, aka Princess George of Battenberg…she was probably best known for her part in the 1934 Gloria Vanderbilt custody trial, when a a former maid of Vanderbilt’s mother, Gloria Morgan, testified that the Marchioness had a lesbian relationship with Morgan…

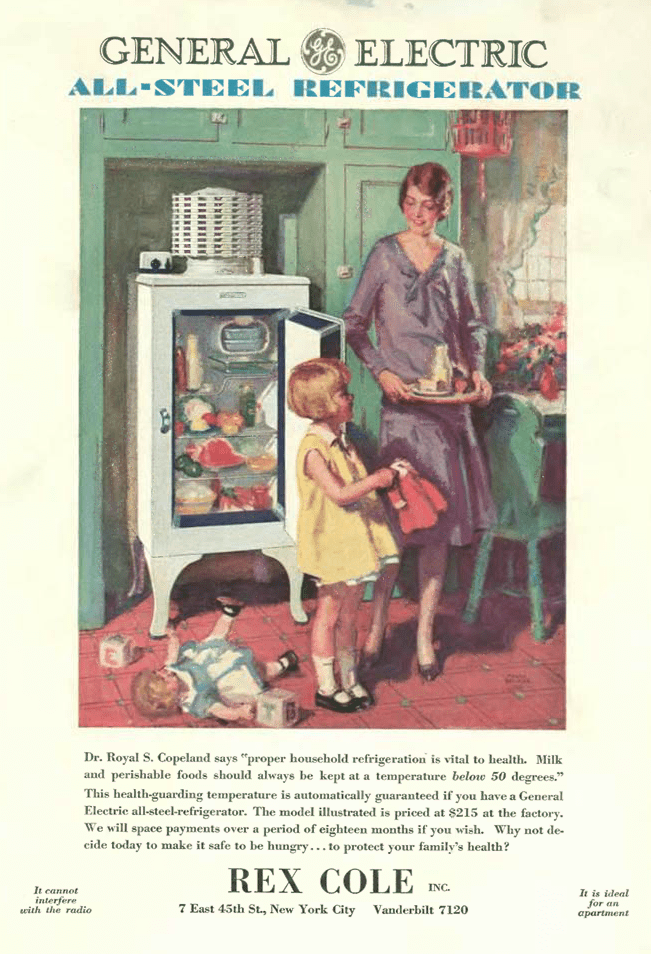

…Helen Hokinson continued loaning one of her “girls” to Frigidaire to extol the wonders of their seemingly indestructible refrigerators…

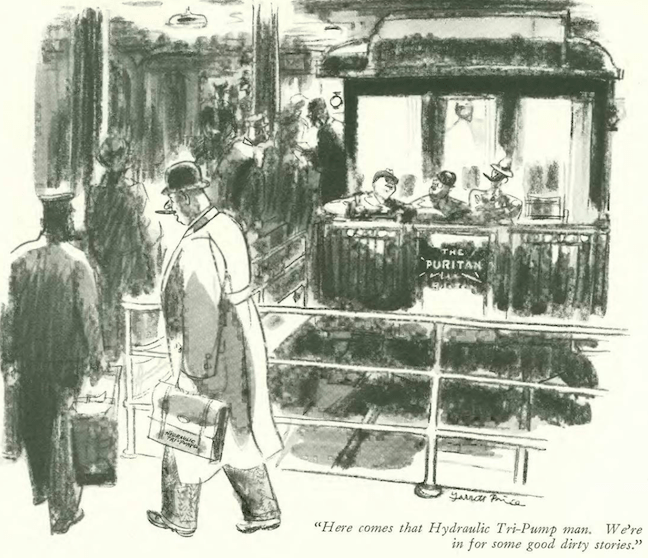

…our Oct. 24 cartoons feature Garrett Price, who brought us the exciting world of the traveling salesman…

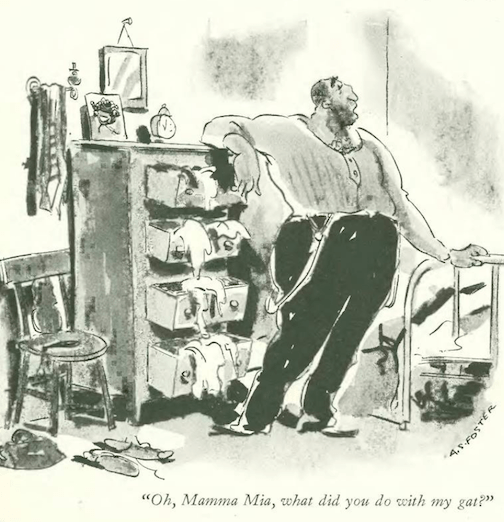

…A. S. Foster served up an Italian stereotype…

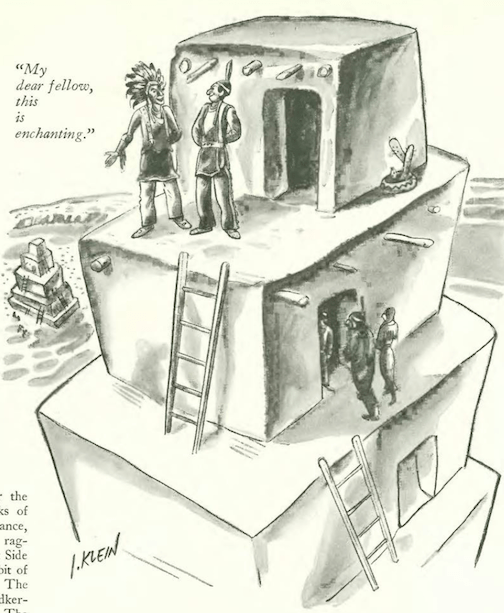

…Isadore Klein, on the other hand, turned a stereotype on its head…

…and we end with Rea Irvin, who gave us what I believe was a first in The New Yorker—a cartoon character breaking the fourth wall…

…by the way, M.F.H. stands for Master of Fox Hounds…I had to look it up.

Next Time: Through a Glass Darkly…