Our sense of what is old and what it is new becomes skewed during periods of rapid change, and such was the case in 1920s New York when large swaths of the old city were swept away and replaced by massive towers that seemingly rose overnight. Places like the Hippodrome Theatre, a 1905 Beaux-Arts confection barely 24 years old, seemed positively ancient in those heady times.

For the most part the New Yorker was enthusiastic about the changing skyline, as its namesake was claiming the crown as America’s premier city; but occasionally a melancholy note would be struck when a familiar institution appeared in decline or fated for the wrecking ball. In the Feb. 9, 1929 “Talk of the Town,” E.B. White wistfully recalled the old days of the Hippodrome, once the largest theatre in the world and the pride of turn-of-the-century New York:

The Hippodrome held such a place in the heart of the New Yorker that the magazine offered further reminiscences in the Feb. 16 issue, this time penned by managing editor Harold Ross:

For demonstrations of diving and “mermaid spectacles,” the Hippodrome stage featured an eight-foot high steel tank in four sections, with a front of plate glass. Manned diving bells were also used to raise and lower “mermaids” during performances.

Ross wrote about the Hippodrome’s “diving girls,” who would dive into a tank of water from a height of 90 feet, sometimes at a serious cost to their health:

Australian swimmer Annette Kellerman was a big draw at the Hippodrome, and helped popularize the sport of synchronised swimming after her 1907 performance of the first water ballet in theatre’s giant plate glass tank. In that same year she shocked Bostonians by appearing on a local beach in a “daring” one‐piece bathing suit (shown above), and was arrested for indecency. This was at a time when a woman’s standard bathing apparel consisted of a blouse, skirt, stockings and swimming shoes.

Unlike some of the unfortunate Hippodrome divers who later lost their eyesight due to cranial pressure from high dives, Kellerman went on to a long and active life (she died in 1975, at age 88). Known throughout the world as Australia’s “Million Dollar Mermaid” (and portrayed by Esther Williams in a 1952 movie by the same name), Kellerman appeared in more than a dozen films between 1909 and 1924. She also launched her own line of swimwear and wrote several books on swimming, beauty and fitness.

* * *

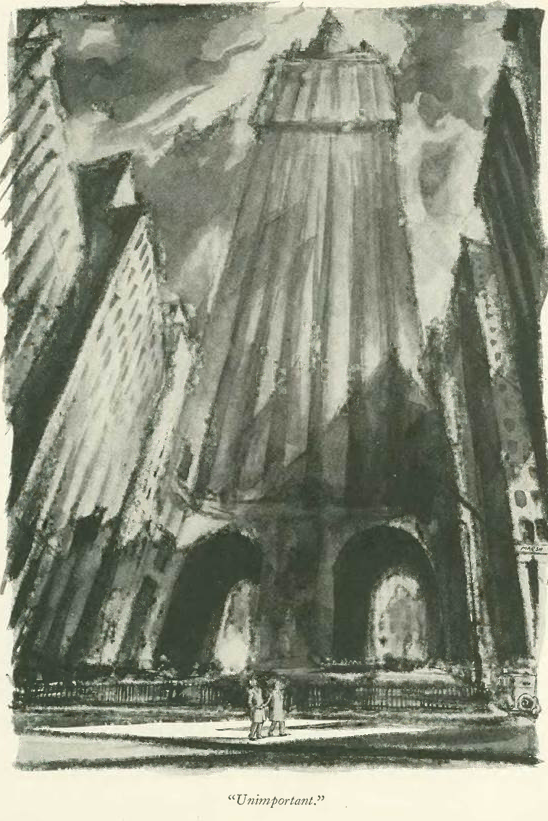

City of Lights

While E.B. White got misty-eyed about the old Hippodrome in the Feb. 9 issue, his fellow New Yorker writer and friend James Thurber was thrilling on the new skyscrapers lighting the city’s skyline:

Thurber noted that “100,000 candlepower” would light the golden crown of the New York Central Building, the tallest structure in the Grand Central complex. Over at the new Chanin Building, a whopping 25 million candle-power would be trained on its art deco crown.

Advertisers in the New Yorker reflected the mood of this new city of skyscraper canyons. From the Feb. 16 issue:

Ralph Ingersoll and Thurber also wrote in the Feb. 16 “Talk” about plans for “Rockefeller City…”

…and as we know, this was to become the famed Rockefeller Center, a complex of 19 buildings covering 22 acres between 48th and 51st streets. Led by by John D. Rockefeller Jr., the complex was conceived as an urban renewal project to revitalize Midtown (hard to imagine today). The land was originally envisioned as a site for a new Metropolitan Opera house, but when financing fell through the land’s owner, Columbia University, leased it to Rockefeller. Of the anticipated effect of the project, Ingersoll and Thurber wrote:

And for the record, the Feb. 9 issue featured another name that would shape the future of the city—J. Pierpont Morgan was the subject of a lengthy two-part profile penned by John K. Winkler.

* * *

Shouts & Murmurs

The Feb. 16 marks a significant date on the New Yorker calendar—the first appearance of Alexander Woollcott’s famed “Shouts & Murmurs” column:

Writing in the “Double Take” section in the July 18, 2012 issue of the New Yorker, Jon Michaud notes that “Shouts & Murmurs” was Woollcott’s personal column, appearing weekly in the magazine for five years. Perhaps no person other Harold Ross himself could be more associated with the earliest origins of the magazine — Woollcott was a colleague of Ross’s at Stars and Stripes during the First World War, and introduced Ross to his first wife, Jane Grant, who was also a considerable influence on the early magazine.

Michaud writes that Woollcott used the column “to opine on, lampoon, and attack the culture and society of the day. In his distinct and at times excessive style, he reviewed books, wrote spoofs, distributed gossip, and generally rankled as many people as he could.” Woollcott ended the column in December 1934, but it was revived in 1992 as a regular venue for many notable humorists, and continues to this day.

* * *

Up In Smoke

Jumping back to the Feb. 9 “Talk of the Town,” we have this complaint from the magazine regarding celebrity cigarette endorsements. Although the magazine derived a lot of revenue from cigarette ads, Harold Ross insisted on a strict separation between editorial and advertising, allowing his writers free reign to bite the hands that fed them, if they so wished:

Here’s the offending ad, which was featured in the Feb. 23 issue:

In the Feb. 9 issue, Groucho Marx couldn’t resist getting in on the endorsement action…

…nor could Ross’s old friend George Gershwin, who touted the health benefits of Lucky Strikes in the Feb. 16 issue…

In other ads from the Feb. 16 issue, we find that for all of the technological advances in the 1920s, a decent car heater still eluded automakers. Hence…

In other ads from the Feb. 16 issue, we find that for all of the technological advances in the 1920s, a decent car heater still eluded automakers. Hence…

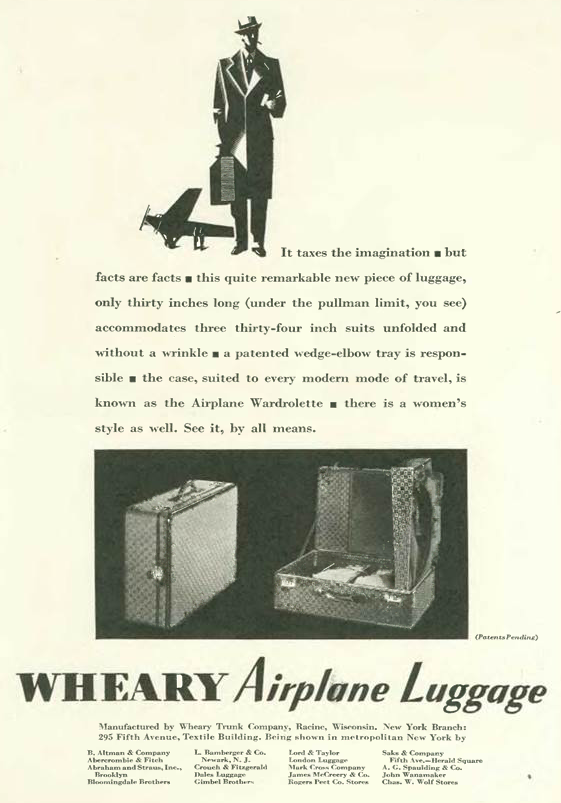

…on the other hand, we also have this very up-to-date product—the forerunner of today’s rolling airplane luggage…

…and if you happened to be flying south, you might have first checked in with Helena Rubinstein to make sure you had the right “face fashions”…

And finally our cartoons, all from the Feb. 9 issue. This first is a six-panel series by Al Frueh that originally ran diagonally, top to bottom, across a two-page spread. It took a shot at the self-promoting police commissioner, Grover Whalen, who was not a friend to the New Yorker due to his ham-fisted approach to Prohibition enforcement…

…and Leonard Dove took a shot at some posh folks outside of their urban element…

…and finally, Alan Dunn examined the wages of beauty…

Next Time: Modern English Usage…