The Roaring Twenties were a strange confluence of the Puritan and libertine, perhaps best represented by Prohibition and the speakeasy night life it inspired. Many if not most of The New Yorker readers of the late 1920s were familiar with these establishments as well as with reliable bootleggers and rum runners. And for those of you following this blog we all know that “Tables for Two” columnist Lois Long was the voice of speakeasy and New York nightlife.

Prohibition did not make consumption of alcohol illegal. The 18th Amendment prohibited the commercial manufacture and distribution of alcoholic beverages, but it did not prohibit their use.

So if you had a connection to a smuggler bringing whisky from Scotland via Canada, for example, you could enjoy a Scotch at home without too much trouble, although the prices could be high. “The Talk of the Town” editors regularly reported black market wine and liquor prices (I include an adjoining Julian de Miskey cartoon):

Note the mention of pocket flasks, which were an important item in a purse or vest pocket when one went to a nightclub or restaurant, where White Rock or some other sparkling water was sold as a mixer for whatever you happened to bring with you. You see a lot of this type of advertisement in the Prohibition-era New Yorker:

I’ll bet those grinning golfers have something in their bags besides clubs.

And then there were ads like these, which I find quite sad:

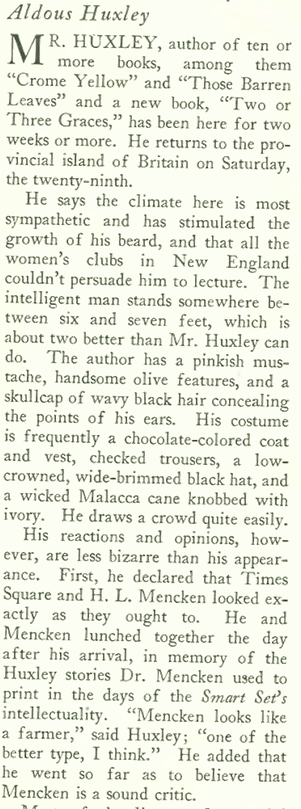

“The Talk of the Town” also commented on the recent visit of British writer Aldous Huxley, who told his New York hosts that he admired American writers Willa Cather and Sherwood Anderson, and he also had praise for writer and critic H.L. Mencken, whom he likened to a farmer “of the better type:”

Other odds and ends from this issue…a clever drawing by Al Frueh for the “Profile” feature on New York Governor Al Smith:

A photo of Al Smith for comparison:

And this bit from “Of All Things,” complete with bad pun/racial slur:

New Yorker readers in 1926 had little reason to believe that in a decade Benito Mussolini would try to make good on his statement and join Adolf Hitler in the next world war.

Here’s a couple more ads from the issue that are signs of those times. Note the listing of Florida locations for those New Yorkers who were flocking to that new winter vacation destination:

And this ad for an electric refrigerator…for those who could afford such newfangled things. The ice man was still plenty busy in 1926, but his days were numbered.

And finally, a nod to springtime, and this excerpt of an illustration by Helen Hokinson for the “Talk” section:

Next Time: After a Fashion…