While the introduction of sound to motion pictures ended the careers of some silent film stars in the late 1920s, Hollywood’s “talkies” offered new opportunities for Broadway stage actors who could now take their vocal talents to the screen and to audiences nationwide.

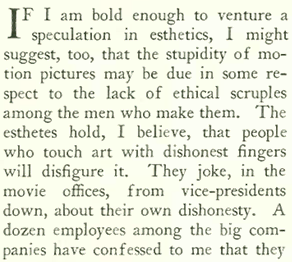

And so began the so-called “Broadway Exodus.” Robert Benchley offered his wry observations on the phenomenon in the May 4, 1929 “A Reporter at Large” column:

Benchley observed that regardless how many Broadway stars moved west, Hollywood Boulevard would never be mistaken for Broadway. However, Benchley himself would catch the bug and head to Tinseltown, appearing in dozens of feature films and shorts including How to Sleep, which would win an Academy Award for “Best Short Subject, Comedy,” in 1935.

* * *

One Who Stayed on Broadway

James Thurber reported in “The Talk of the Town” that famed boxing champion Jack Johnson was a common sight on the sidewalks of Broadway. Thurber noted that Johnson, the first African American world heavyweight boxing champion (1908–1915), had fallen on less glamorous days, but still appeared fit at age 51.

Thurber noted that Johnson was planning to sell stories of his life, and possibly get into vaudeville. The boxer also mused that who could lick either of the heavyweight champs of the 1920s, Gene Tunney and Jack Dempsey…

…and Thurber shared a strange account regarding the thickness of Johnson’s skull, which apparently bested that of an ox…

Johnson continued professional boxing until age 60, and thereafter participated in boxing exhibitions in various venues until his death at age 68 in a car crash near Raleigh, NC. It was reported that Johnson was racing angrily from a nearby diner that had refused to serve him when he lost control and hit a light pole.

* * *

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

Anyone who thinks the recent squabbles over Planned Parenthood are anything new might do a little reading on the life of Margaret Sanger, who opened the first birth control clinic in the U.S. in 1916 (in Brooklyn) and was subsequently arrested for distributing information on contraception. In 1929 she was again arrested for operating a “secret” birth control clinic in the basement of a Manhattan brownstone. On March 22, 1929, the New York Police Department sent an undercover female detective, Anna McNamara, to Sanger’s clinic. Posing as a patient who wished to avoid another pregnancy, McNamara was advised on various forms of contraception. She later returned to the clinic as part of the police raid, during which she seized a number of confidential patient files. At Sanger’s subsequent court hearing, McNamara learned first-hand about the importance of patient confidentiality. From the May 4 “Talk of the Town”…

Recalling her arrest in a 1944 article, “Birth Control: Then and Now,” Sanger wrote that McNamara taunted her during the raid when she was told that she had no right to touch private medical files. Sanger wrote “I shall never forget the color of Mrs. McNamara’s face when she heard this medical testimony recited several days later in Magistrates’ Court at the hearing. She was totally unprepared for this embarrassing revelation of her own organs.” The New Yorker made note of this…

Sanger would continue to work for birth control until her death in 1966. Although her name is still invoked in debates over abortion, Sanger herself was generally opposed to abortion, maintaining that contraception was the only practical way to avoid it.

* * *

Please Sit Still

The “Talk of the Town” also looked on American Impressionist painter Childe Hassam, who demonstrated the challenges of painting en plein air…

…and found it difficult to finish a farmhouse sketch when a door was unexpectedly closed on his subject…

* * *

All That Jazz

As Lois Long’s contributions to her “Tables for Two” column grew ever more infrequent, it was clear that she was wearying of the nightlife scene. Now 28 and a young mother, “Lipstick” was shedding her image as a fun-loving flapper and devoting more time and energy to her fashion column, “On and Off the Avenue.” Nevertheless, she still found the time to visit the Cotton Club and proclaim Duke Ellington’s jazz orchestra as “the greatest of all time”…

…although her other observations of the New York nightclub scene appear to have been hastily dashed off…

* * *

Electric Wonders

The May 4 issue updated readers on some of the latest gadgets available to modern households in 1929. I particularly like the device that allowed your vacuum to blow “moth poison” into your garments…

* * *

From Our Advertisers

One thing you notice about 1920s advertising is the amount of turgid copy they contain…I suppose without distractions such as TV and iPhones people actually took the time to read all of these bloated messages, such as this one from Whitman’s that suggested a box of candy is more than a box of candy…

…or how about this lengthy appeal from Kodak, which used guilt to convince you to get some film of grandma while she was still “at her best…”

…the makers of Spud promised a “new freedom” and a “16% cooler smoke” to the users of its menthol-laced cigarettes. Spuds were the first menthol cigarettes, developed in 1924 by Ohioan Lloyd “Spud” Hughes, who sold them out of his car until the brand was acquired in 1926 by The Axton-Fisher Tobacco Company. By 1932 Spud was the fifth-most popular brand in the U.S., and had no competitors in the menthol market until Brown & Williamson launched their Kool brand in 1933. The Spud brand died out by 1963 (along with, presumably, many of its customers)…

…leveraging the popularity in the 1920s of knights and fairies, as well as the Anglo- and Francophila of New Yorker readers, “Mrs. Marie D. Kling” hoped to entice city dwellers up to the burbs in Scarsdale…

…our cartoons are courtesy of Barbara Shermund, who looked in on a couple of debs performing their daily exercises…

…while down in the parlor, Rea Irvin captured the horrors inflicted by an author’s tedious reading…

…and finally, Peter Arno probed the depths of sanctimony…

Next Time: Waldorf’s Salad Days…