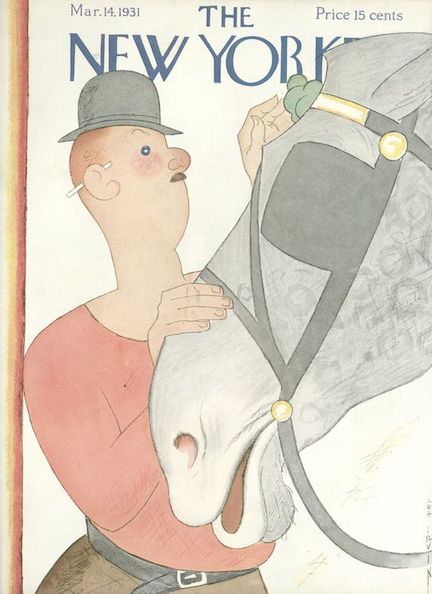

Despite the deepening economic depression, work continued apace on a number of large building projects that were transforming the Manhattan skyline, including the Empire State Building, which was being readied for its May grand opening.

Developers also looked to the future, including the Rockefeller family, who commissioned a massive project in Midtown — 14 buildings on 22 acres — that would be one of the greatest building projects in the Depression era…

…so great that even E.B. White found the proposed Rockefeller Center difficult to fathom:

* * *

Star Power

The Depression years also offered lesser diversions, and there’s nothing like celebrity culture to distract one’s mind from daily woes. For our amusement, E.B. White offered up the recent nuptials of Olympic swimmer (and future Tarzan movie star) Johnny Weissmuller and Ziegfeld singer/showgirl Bobbe Arnst…

…of course there’s no better place to find celebrities than Hollywood, where Marlene Dietrich was collecting good reviews for her latest film, Dishonored. Critic John Mosher was absolutely gah gah over the German actress…

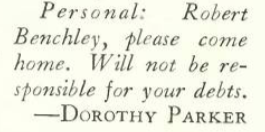

…if you preferred the stage to the screen, you could check out a show on Broadway, but if you were Dorothy Parker (subbing as theater critic for her pal Robert Benchley), you’d have trouble finding anything worth watching. Her latest review was something of a double-whammy: not only was the play a stinker, but it was written by one of Parker’s least-favorite authors, A. A. Milne…

* * *

Cinéma Vérité

However, Dorothy Parker could have found consolation in the fact that someone, somewhere, had it a lot worse. For example, the eight defendants in a Soviet show trial, filmed for the edification of the masses and as a warning to opponents of the Bolshevik Revolution. In this warm-up for the Great Terror to come, five of the eight were condemned to death after making what were obviously forced confessions. John Mosher had this to say about the real-life horror film:

* * *

End of the World, Part II

In my last post we saw how E. B. White mourned the end of The New York World newspaper in a lengthy “Notes and Comment” entry. By contrast, White’s colleague Morris Markey wasn’t shedding any tears for a newspaper he believed had seen its better days. Markey shared his observations in his March 14 “Reporter at Large” column…

…Markey described the newspaper’s final day with veteran rewrite man Martin Green quietly typing his last story amid the tears and wisecracks of reporters suddenly out of work…

…the end of the World was also on the mind of Gardner Rea, who contributed this cartoon to the March 21 issue:

* * *

The State of Modern Man

Lois Long continued her “Doldrums” series by looking at the condition of bachelor life in the city, and like everything else among the younger generation she found it wanting. Lois was a ripe old 29 when she wrote this, but given how radically life had changed since the Roaring Twenties, a wide gulf now separated those days from the more somber Thirties. Note how Long, who embodied flapper life in her defunct “Tables for Two” column, described herself as a “modest, retiring type” who knew nothing about men. Around this time Long was preparing to divorce husband (and New Yorker cartoonist) Peter Arno after a brief, tempestuous marriage…

* * *

From Our Advertisers

In those depressed days the makers of Buick automobiles decided to look to a brighter future, imaging how the boys of the present would be drivers of Buicks in the future…this kid probably ended up driving a tank or a Jeep rather than a Buick when 1942 rolled around…

…Adele Morel also wanted you to think about the future, and how to hold off those inevitable wrinkles…note the message near the bottom: “Do you realize that a youthful appearance means happiness?”…

…I included this ad for River House because of its sumptuous detail…it rather resembles a 17th century European silk tapestry, and the people depicted look like they could be from that time as well…

…speaking of another age, we have this Murad ad by Rea Irvin, illustrating office behavior that was quite common in the 20th century…

…on a related note, in the cartoons E. McNerney illustrated a “Me Too” moment…

…when Otto Soglow published his first Little King strip in the June 7, 1930 issue, it caught the eye of Harold Ross (New Yorker founding editor), who asked Soglow to produce more. After building up an inventory over nearly 10 months, Ross finally published a second Little King strip, which you see below. The strip would become a hit, and would launch Soglow into cartoon stardom…

…William Dwyer offered a dim view of a man’s stages of life in the first of two cartoons he contributed to The New Yorker…

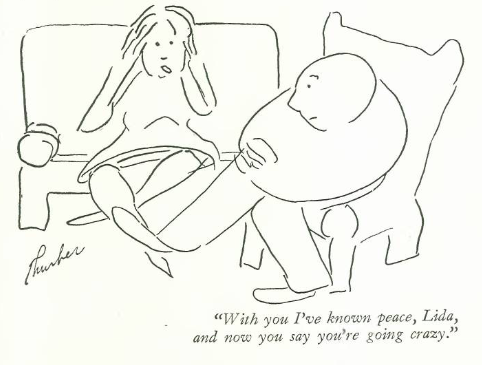

…James Thurber shared tears with some sad sacks…

…in a few years Leonard Dove’s housewife would see her fears realized as another world war would loom on the horizon…

…and we end with Garrett Price, and an appreciation for fine art…

Next Time: Killer Queen…