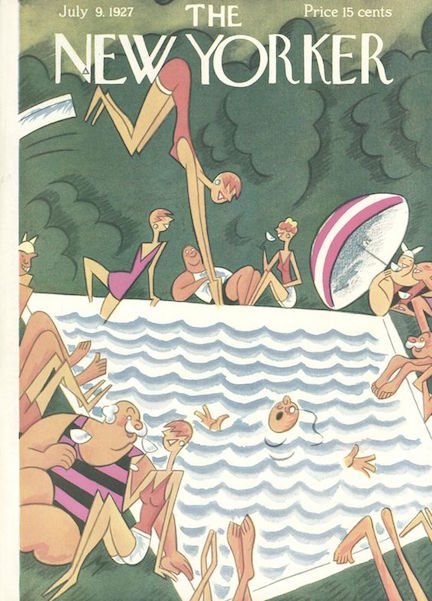

The July 1927 issues of the New Yorker were filled with news of yacht races, polo matches and golf tournaments as the city settled into the heart of the summer. The artist for the July 9 cover, Julian de Miskey, was in the summertime mood with this lively portrayal of Jazz Age bathers:

Although Julian de Miskey (1898–1976) was was one of the most prolific of the first wave of New Yorker artists, his work seems to be little known or appreciated. But more than forty years after his death his influence is still felt in the magazine, particularly in the spot illustrations and overall decorative style that grace the pages of “The Talk of the Town.”

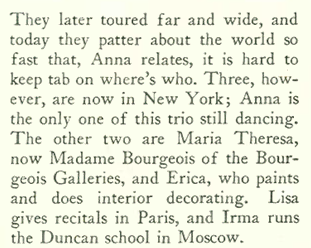

Here is a sampling of de Miskey’s spot illustrations for “Talk” in the July 9 and July 16, 1927 issues…

…and here are examples of spot illustrations for some recent (Aug-Sept. 2016) New Yorker “Talk” sections, as rendered by Antony Huchette (which also reference Otto Soglow’s spot work for The New Yorker)…

De Miskey did it all–spots, cartoons, and dozens of covers. A member of the Woodstock Art Association, de Miskey was well known in the New York art circles of his day, rubbing elbows in the Whitney Studio Club in Manhattan with artists including Edward Hopper, Guy Pene du Bois, Mabel Dwight and Leon Kroll. De Miskey also illustrated and designed covers for a number of books, studied sculpture and created stage sets and costume designs.

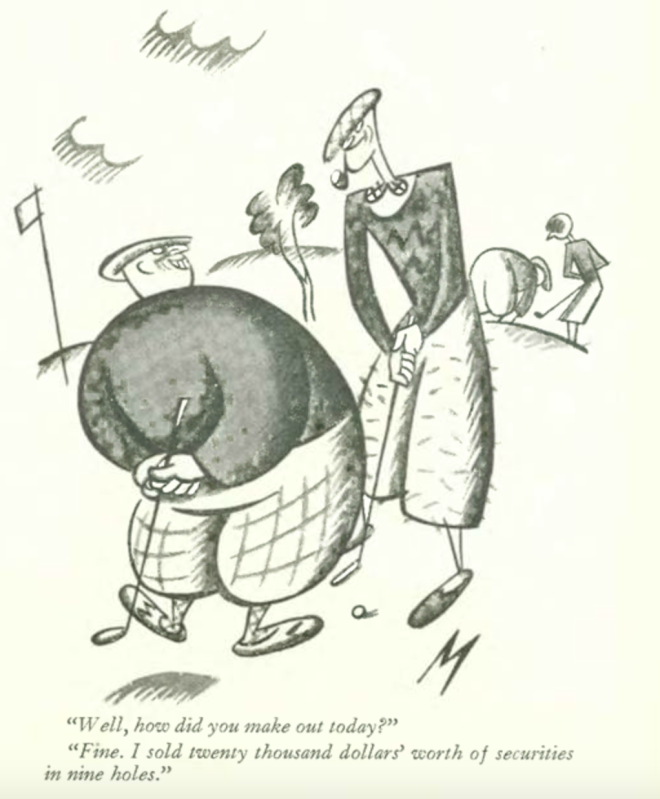

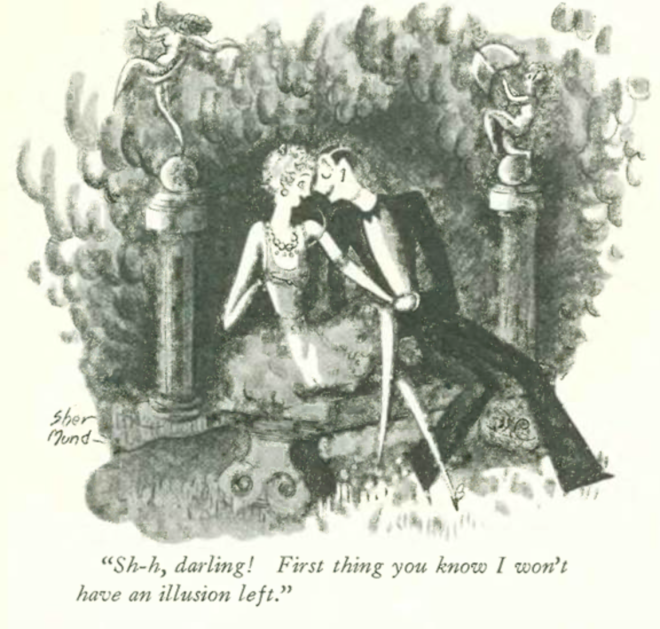

The June 9 issue also featured this cartoon by de Miskey:

* * *

President Calvin Coolidge fled the bugs and heat of Washington, D.C. for cooler climes in the Black Hills of South Dakota. The New Yorker regularly mocked Coolidge’s dispatches from the Dakotas, including this item in “Of All Things”…

The magazine’s July 16 issue added this observation in “The Talk of the Town”…

Closer to home, M. Bohanan offered an urban sophisticate’s take on nature:

For those who couldn’t flee the city, respite was sought in Central Park, as illustrated by Constantin Alajalov for “The Talk of the Town…”

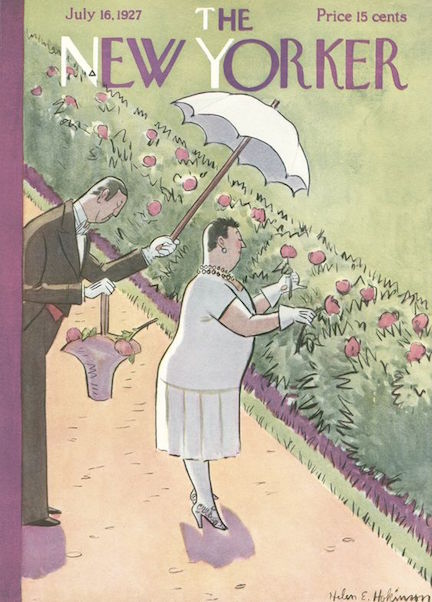

Summer themes continued with the July 16 issue, which featured a cover by Helen Hokinson depicting one of her favorite subjects–the plump society woman:

From 1918 to 1966, thousands of New Yorkers attended summer open-air concerts at Lewisohn Stadium, an amphitheater and athletic facility on the campus of the City College of New York. For many years Willem Van Hoogstraten conducted the nightly concerts, including the summer of 1927 when George Gershwin played his Rhapsody in Blue to adoring crowds.

And finally, another illustration in the “Talk of the Town” of summer in the city, this a teeming Coney Island beach courtesy of Reginald Marsh…

However, if you wanted to avoid the rabble at the beach, you could fly over them–in style, of course…

Next Time: Picking on Charlie Chaplin…