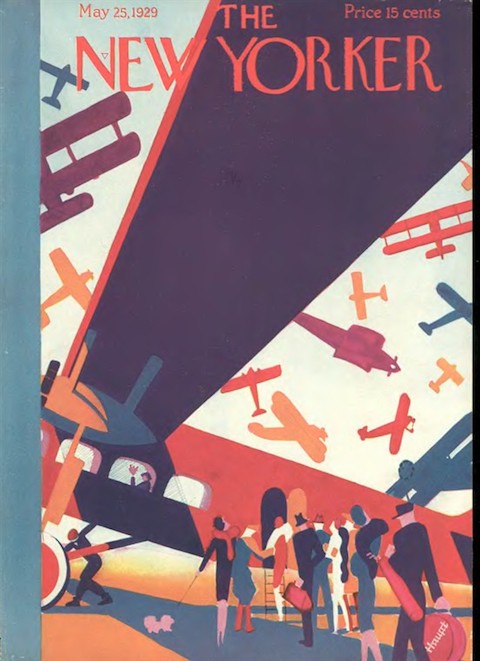

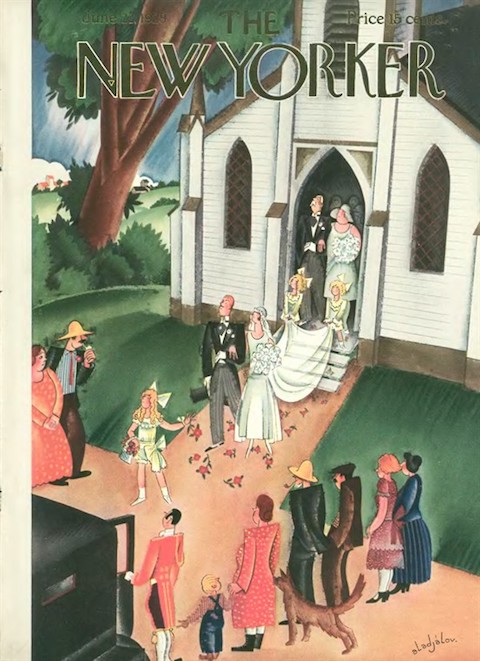

Above: The split image is from a New Yorker video: Eighty Years of New York City, Then and Now.

While the Empire State Building developers were preparing to reduce the old Waldorf-Astoria Hotel to rubble, another venerable relic of the Victorian age, the Murray Hill Hotel, was still clinging to the earth at its prime location next to the Grand Central Depot.

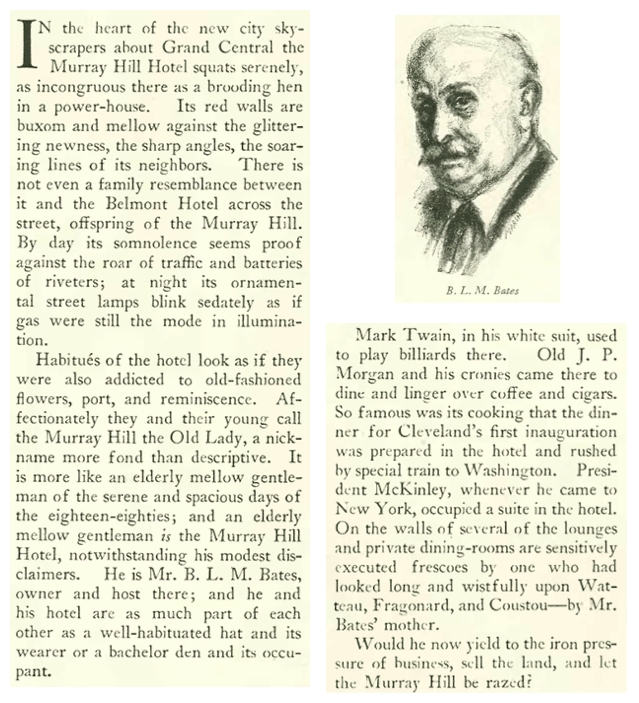

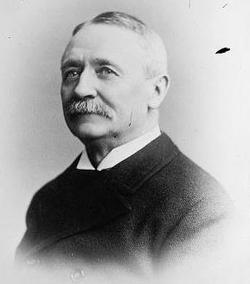

The hotel’s survival was due in part to its owner, Benjamin L. M. Bates (1864-1935), who seemed as much a part of the hotel as its heavy drapes and overstuffed chairs. Bates, who started out at the hotel as assistant night clerk, was profiled in the June 15, 1929 issue by Joseph Gollomb (with portrait by Reginald Marsh) Some excerpts:

The hotel was just 26 years old when Bates bought it in 1910. But by the Roaring Twenties Murray Hill Hotel seemed as ancient as grandmother’s Hepplewhite…

…but to the very end it continued to be a popular gathering spot for New York notables, including Christopher Morley’s prestigious literary society, the Baker Street Irregulars…

…with the hotel’s prime location near Grand Central Depot (and its replacement, Grand Central Station), the party couldn’t last forever, and the Murray Hill Hotel yielded to the wrecking ball in 1947…

Some parting notes about the Murray Hill Hotel: In 1905, delegates from 58 colleges and universities gathered at the hotel to address brutality in college football and reform the sport. They formed the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States, which would later become the NCAA.

The hotel was also the site of a massive explosion in 1902, when workers constructing a subway tunnel under Park Avenue accidentally set a dynamite shed ablaze. Every window along Park Avenue and 40th Street was blown out, and the blast opened a pit, 10 feet deep and 30 feet wide, in front of the building. Five people were killed by the blast—three of them at the Murray Hill Hotel.

* * *

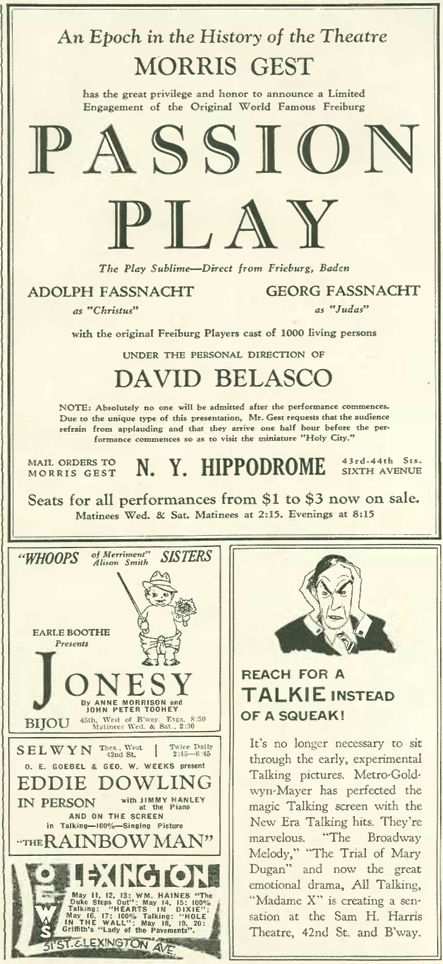

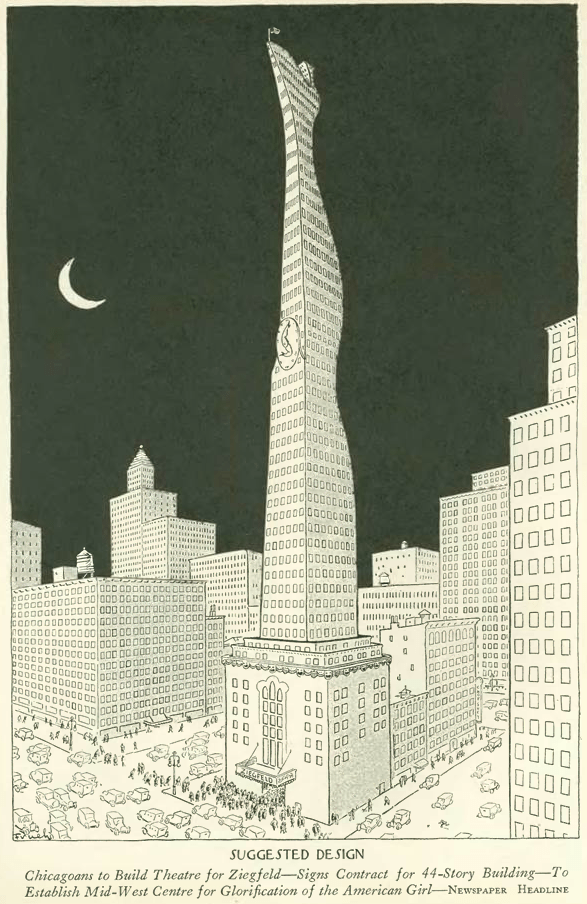

Irwin S. Chanin, fresh from erecting his Art Deco masterpiece, the Chanin Building, was now setting his sights on the Century Theatre, barely twenty years old but already obsolete due to its poor acoustics and inconvenient location. “The Talk of the Town” takes it from there…

As the Century Theatre marked its last days, an older and more successful theater in the Bowery went up in flames. The Thalia Theatre (also known as “Bowery Theatre” and other names) was a popular entertainment venue for 19th century New Yorkers and for the Bowery’s succession of immigrant groups. A series of buildings (it burned four times in 17 years) housed Irish, German and Yiddish theater and later Italian and Chinese vaudeville. The 1929 fire marked the end of the line. “Talk” noted its passing…

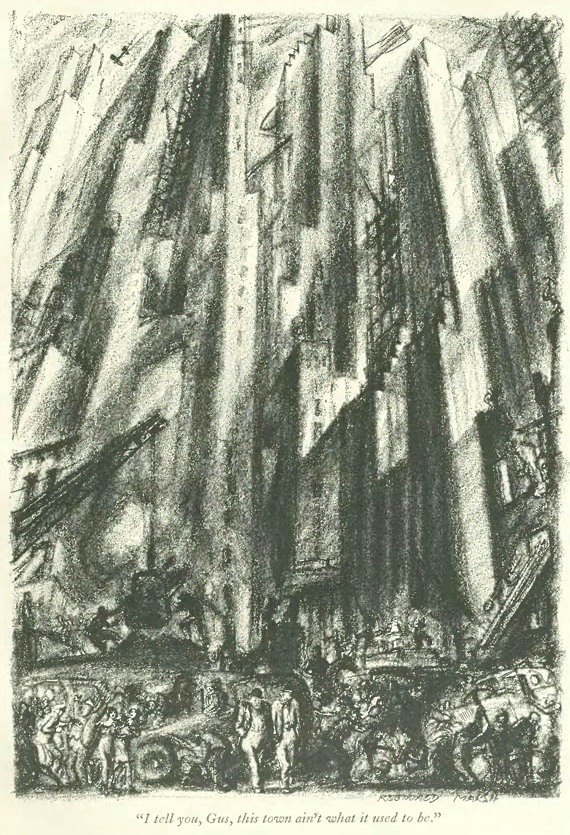

While we are on the subject of the changing skyline, I will toss in this cartoon from the issue by Reginald Marsh…the caption read: “I tell you, Gus, this town ain’t what it used to be.”

* * *

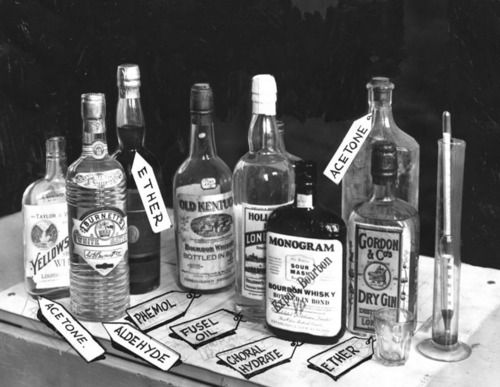

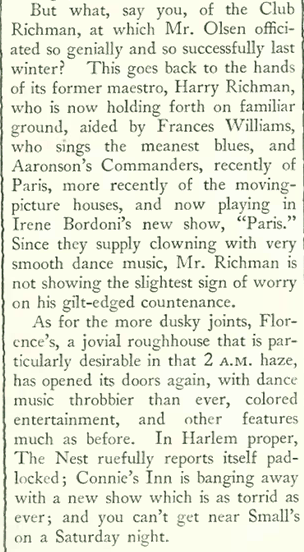

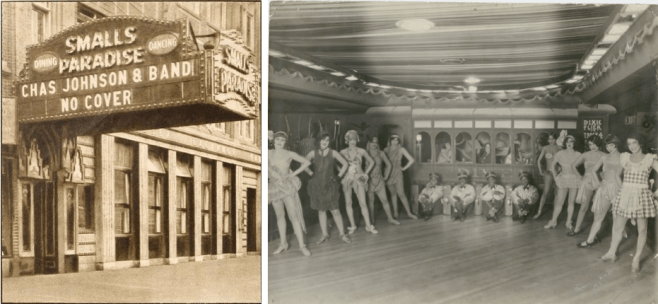

Down for the Count

There was a bit of a sensation in the June newspapers when a European count was arrested for running a bootlegging ring among socially prominent circles. A headline in a June 8, 1929 edition of the New York Times shouted: LIQUOR RING PATRONS FACING SUBPOENAS; Socially Prominent Customers Are Listed in Papers Found in de Polignac Raids. COUNT SAILS FOR PARIS. Goes, After Nearly Losing Bail Bond, Smilingly Calling the Affair ‘Misapprehension.’

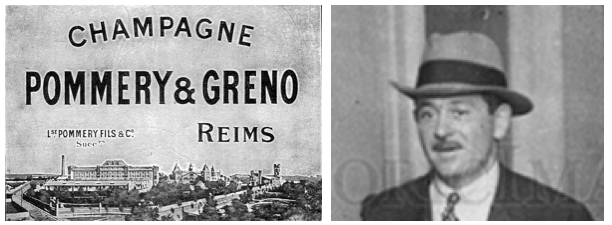

What the Times so breathlessly recounted were the activities of Count Maxence de Polignac (1857–1936), who owned one of France’s most prominent Champagne houses, Pommery & Greno.

The Times reported that an undercover federal agent, William J. Calhoun, led a raid that netted the Count and 34 others in a liquor ring connected to many Park Avenue and Fifth Avenue residents. Calhoun’s agents interrupted the Count’s morning bath (at his suite in the Savoy-Plaza Hotal) to make the arrest. They seized more than “seven cases of champage and liquors” in the suite, which the count said were for his personal use. Denying all charges, de Polignac was nevertheless arrested. Thanks to a guarantee provided by his friends at the Equitable Surety Company, he made the $25,000 bail and quickly set sail for Paris. “Talk” reported…

“Talk” concluded the dispatch with some notes on Calhoun’s character as a federal agent…

…and a final bit of trivia, Count Maxence de Polignac was the father of Prince Pierre of Monaco, Duke of Valentinois, who in turn was the father of Rainier III of Monaco, who famously married the actress Grace Kelly. Grace Kelly, by the way, was born in November 1929, just months after her grandfather-in-law’s run-in with Prohibition authorities.

* * *

Underwhelmed

Once again “Talk” looked in on aviation hero Charles Lindbergh, and his dispassionate approach to matters of fame…

* * *

Mr. Monroe Outwits a Bat

James Thurber submitted a humorous piece on a husband and wife at a weekend cabin retreat. The husband encounters a bat, and feigns to dispatch it while his wife remains behind closed doors. A brief clip:

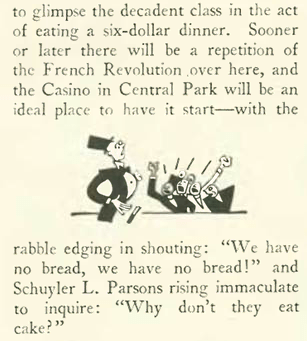

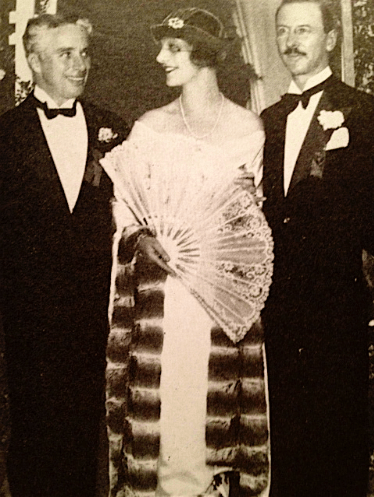

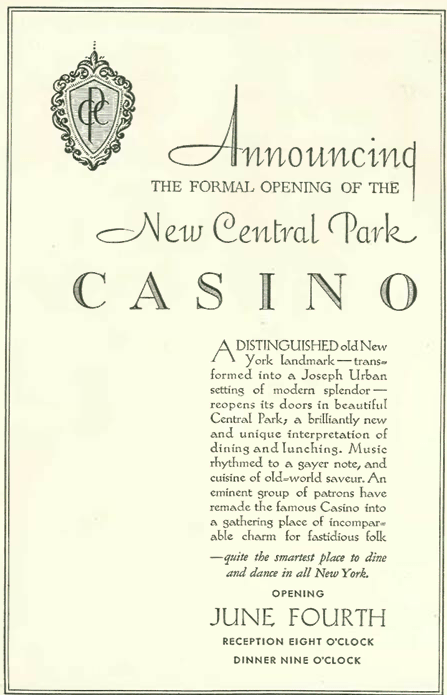

Thurber’s office mate and friend, E.B. White, penned a piece on the opening of the Central Park Casino (“Casino, I Love You”) in which he pretended to be a hobo loitering outside the Casino’s recent grand re-opening. Some excerpts…

White’s character confuses Urbain Ledoux with Casino designer Joseph Urban. Ledoux was known to New Yorkers as “Mr. Zero,” a local humanitarian who managed breadlines for the poor. White’s character continues to name off the notables present at the event…

* * *

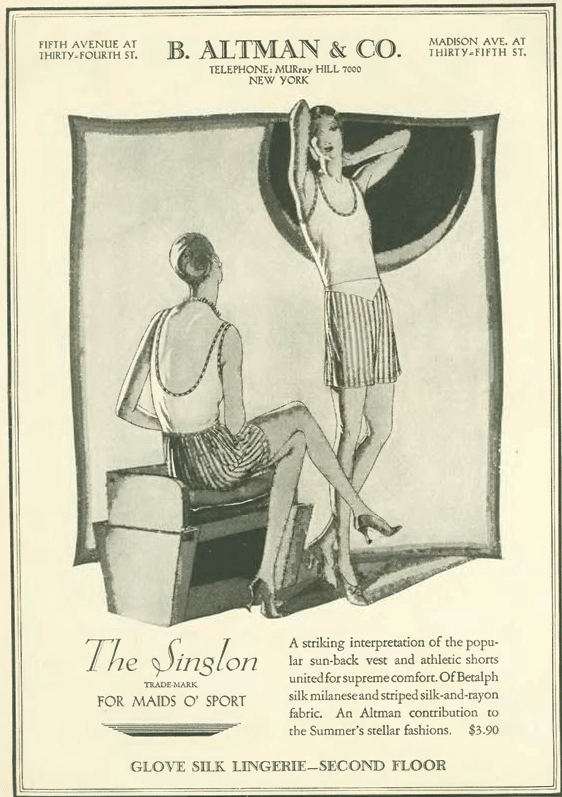

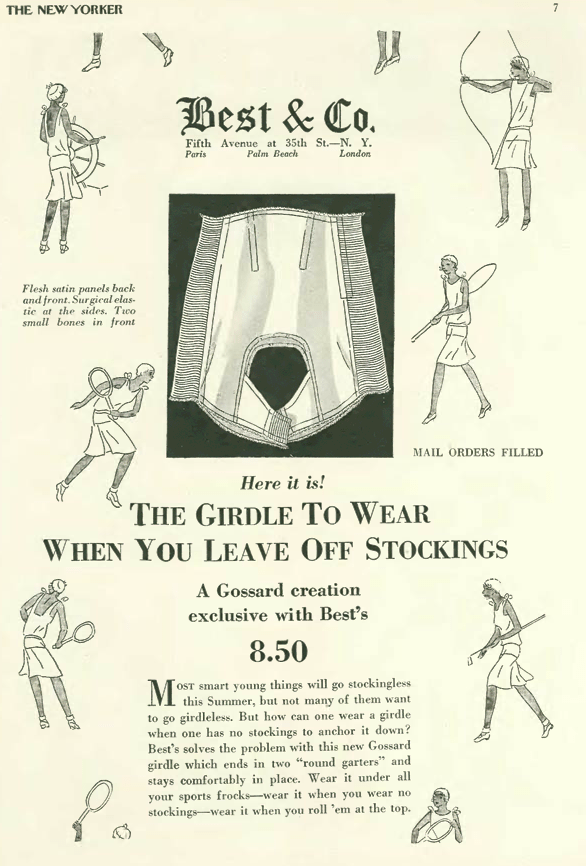

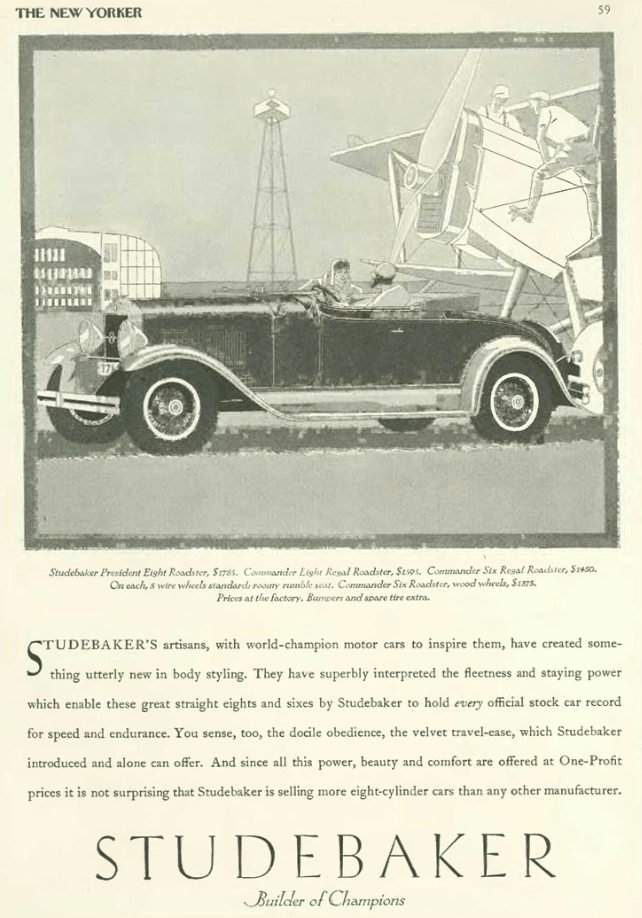

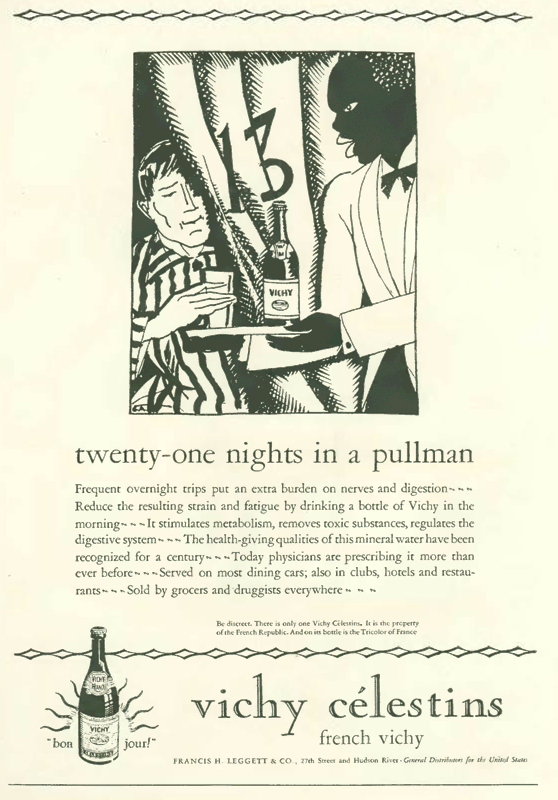

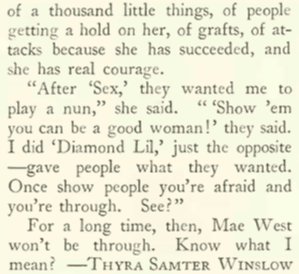

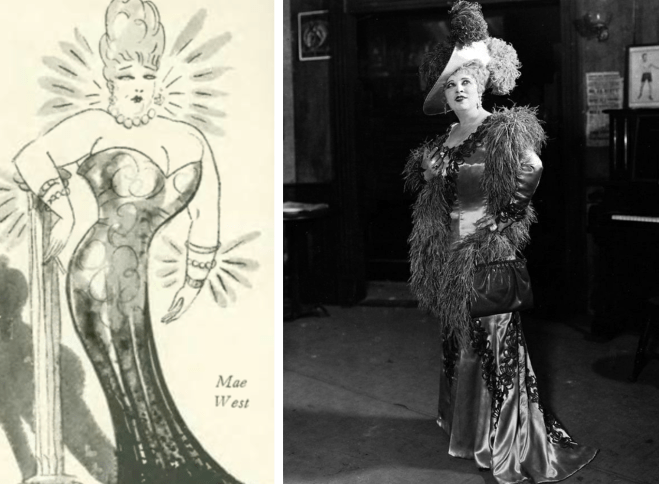

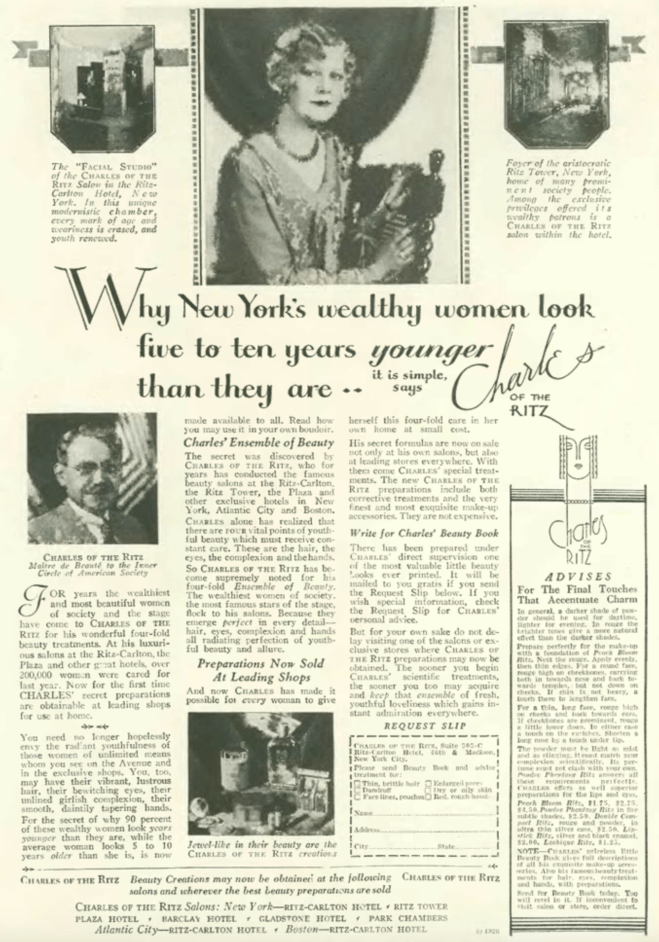

From Our Advertisers

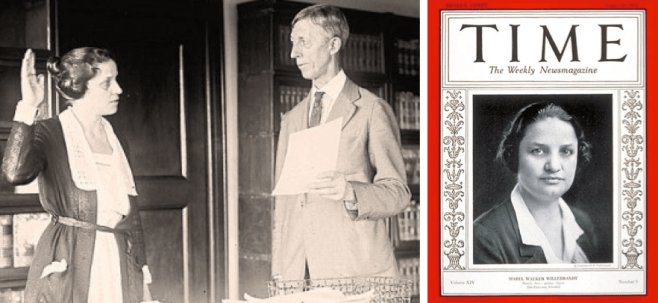

We begin with a Pond’s cold cream ad featuring Janet Newbold (1908-1982), who was known in some circles as “the most beautiful woman in New York”…

…some of the more colorful ads in the June 15 issue included this entry by Jantzen…

…and this ad for the REO Flying Cloud, a name that suggested speed and lightness, and changed the way cars would be named in the future (e.g. “Mustang” rather than “Model A”)…

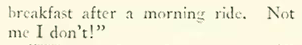

…and if you think gimmicky razors are something new, think again…

…this ad announcing Walter Winchell’s employment with the New York Daily Mirror is significant in that in marks the beginning of the first syndicated gossip column. Winchell’s column, On-Broadway, was syndicated nationwide by King Features. A year later he would make his radio debut over New York’s WABC…

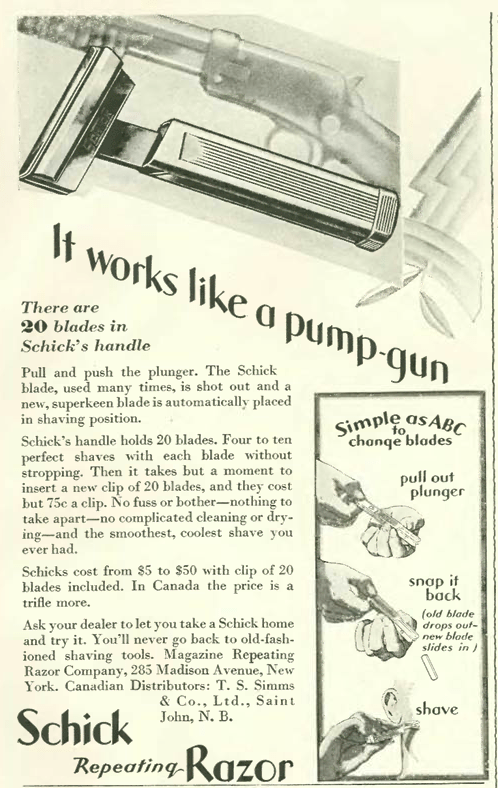

…for our June 15 cartoons, Isadore Klein confirms that stereotypes regarding American tourists haven’t changed much in 90 years…

…a quick footnote on Klein. In his long and colorful career, he would contribute cartoons to the New Yorker and many other publications. He also drew cartoons for silent movies, including Mutt and Jeff and Krazy Kat, and later worked for major animation studios including Screen Gems, Hal Seeger Productions, and Walt Disney. He was a writer and animator for such popular cartoons as Mighty Mouse, Casper, Little Lulu and Popeye.

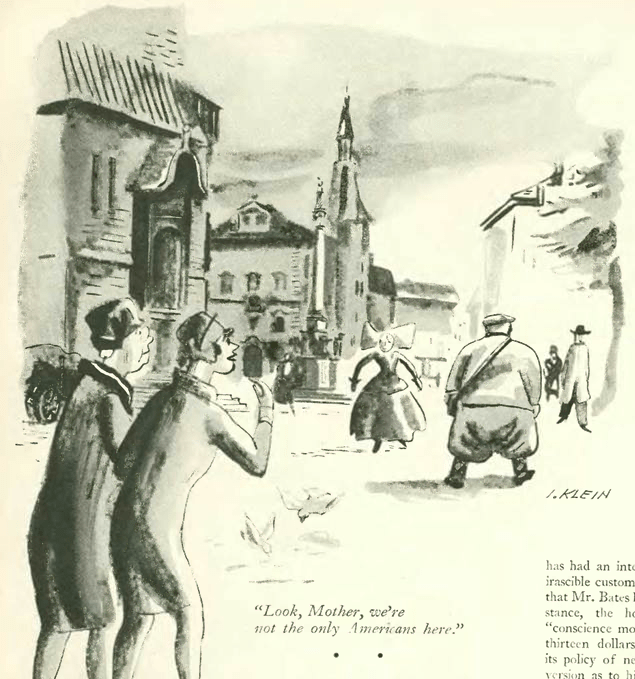

…Belgium-born artist Victor De Pauw depicted President Herbert Hoover picnicking, as viewed through his security detail…

…and a quick note on De Pauw…well known during his lifetime, he illustrated seven covers for The New Yorker and drew many social and political cartoons for magazines such as Vanity Fair, Fortune and Life. He also had a career as a serious painter, and some of his work can be found at the Museum of Modern Art…

…Helen Hokinson looked in on two of her society women in need of some uplift…

…and Leonard Dove looked in on another enjoying a soak…

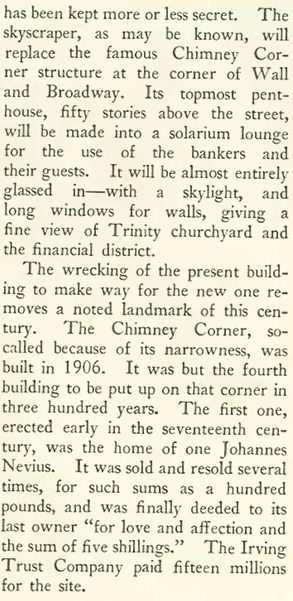

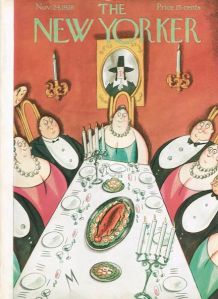

Moving along to the June 22, 1929 issue, “The Talk of the Town” offered more news on the city’s changing skyline…

…and noted that the slender 1906 “Chimney Corner” building at Wall and Broadway had a date with the wrecking ball…

* * *

Apartheid on the Seas

“Talk” also featured this sad account of a theatrical company setting sale for England and discovering that racial discrimination did not end at the docks of New York Harbor. It is also sad that The New Yorker didn’t seem to have any problem with this injustice, and rather saw it as nothing more than fodder for an amusing anecdote…

* * *

The profile for June 22 featured 100-year-old John R. Voorhis (1829-1932), Chairman of New York City’s Board of Elections. A fixture of the Tammany Hall Democratic political machine, in 1931 Tammany members created a special title for the old man—Great Grand Sachem. He died the next year at age 102.

* * *

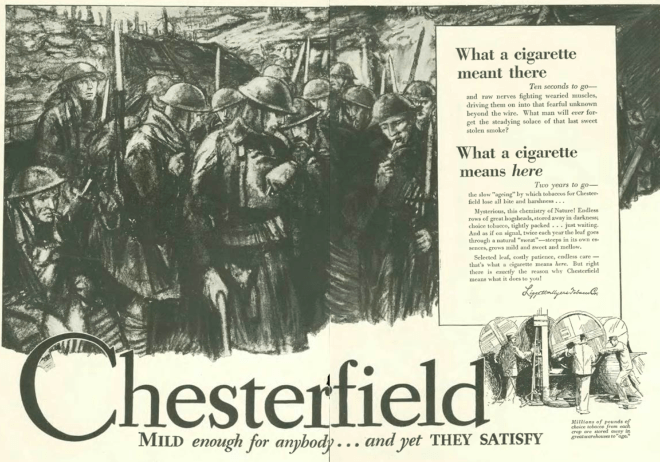

From Our Advertisers

Another colorful entry from the makers of Jantzen swimwear to celebrate the summer season…

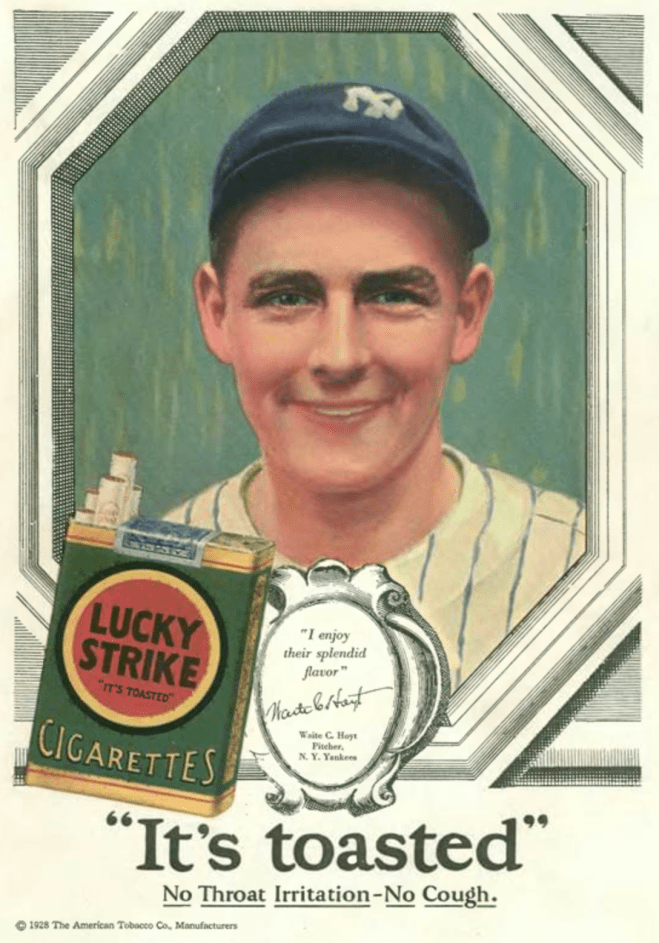

…famed composer George Gershwin urged his fans to light up a Lucky Strike…

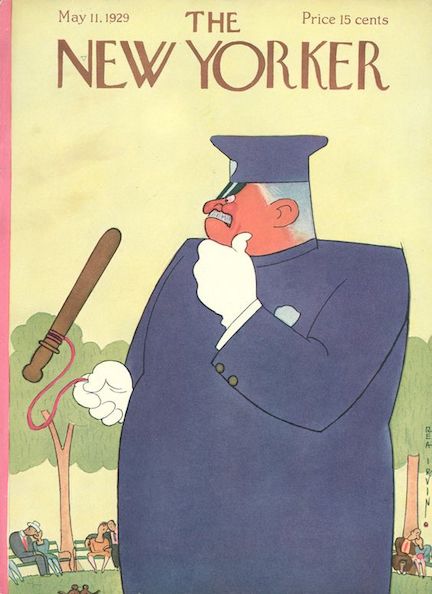

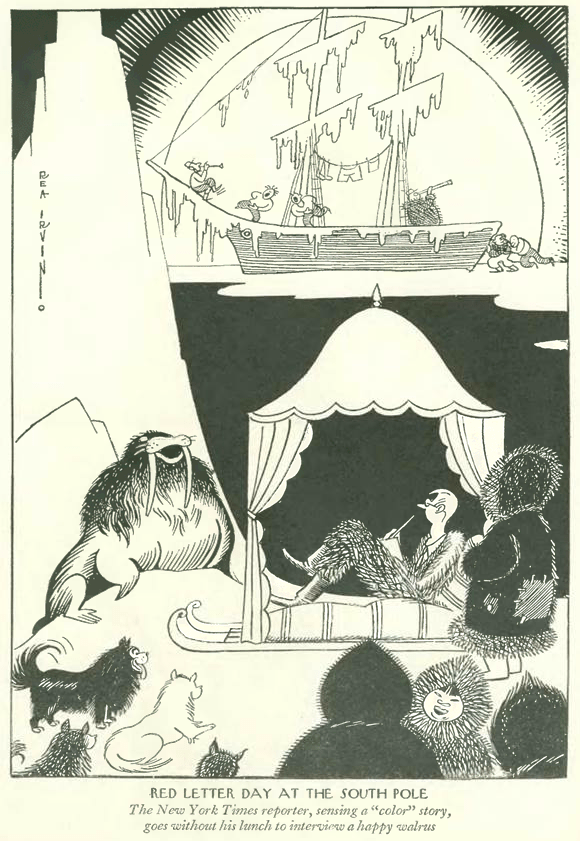

…and with help from Rea Irwin, Knox Hatters offered yet another example of the faux pas one might suffer without the proper headgear…

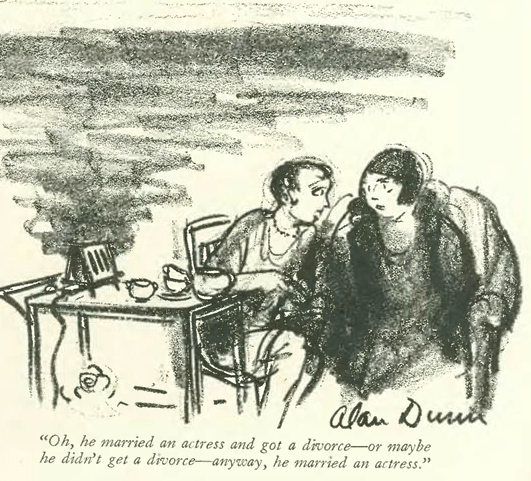

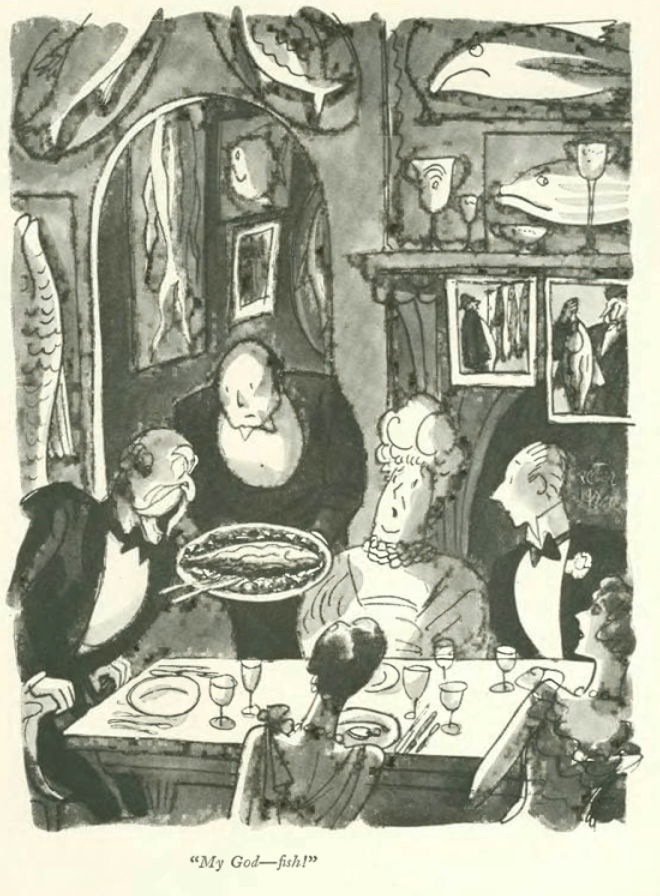

…for our June 22 cartoons, Helen Hokinson caught up with some American tourists…

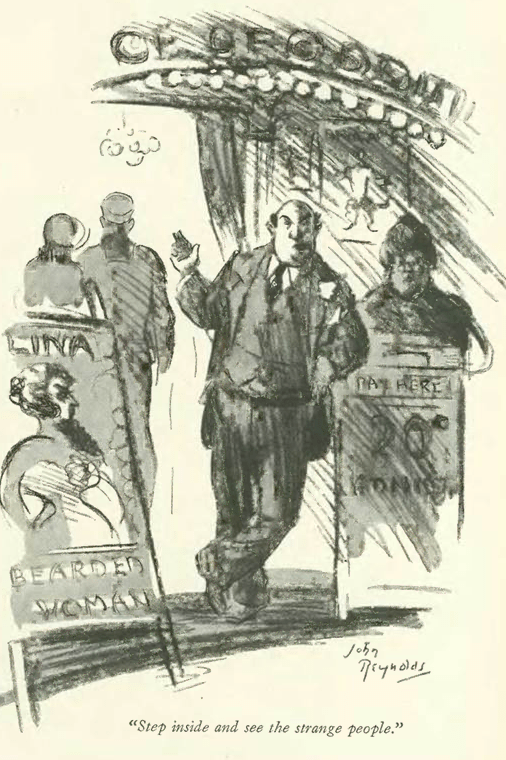

…John Reynolds found a bit of irony in one carnival barker’s claim…

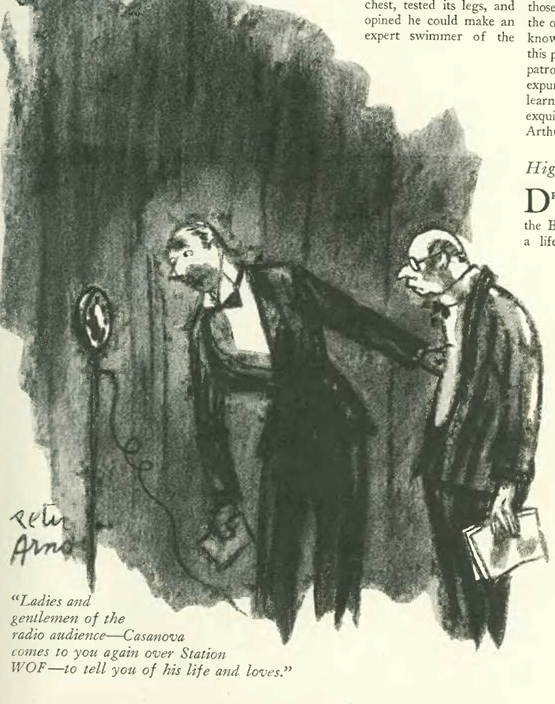

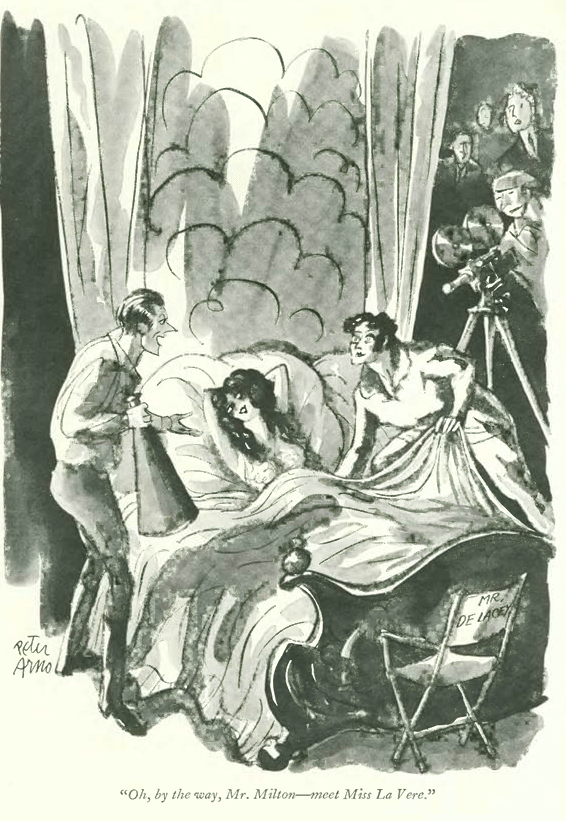

…and Peter Arno revealed a less than glamorous face behind a radio broadcast…

Next Time: New York, 1965…