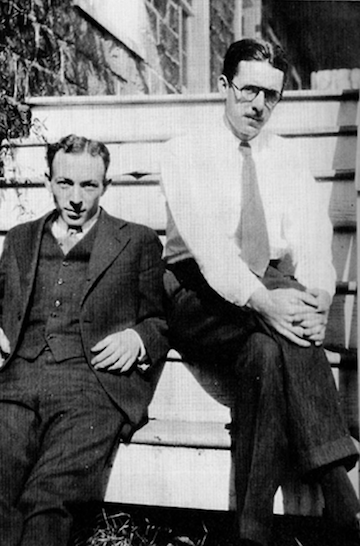

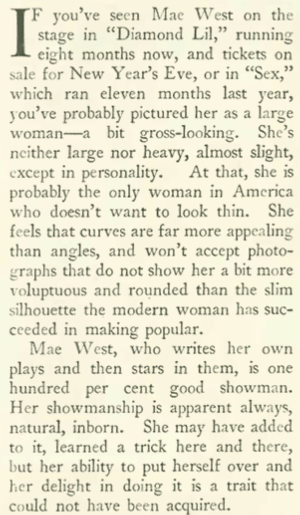

James Thurber and E.B. White shared an office at the New Yorker that has been described as “the size of a hall bedroom.” This proximity doubtless supported a rich exchange of ideas that coalesced in their 1929 bestseller, Is Sex Necessary? Or, Why You Feel the Way You Do.

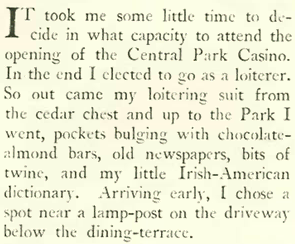

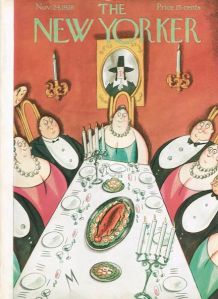

A spoof of popular sex manuals and how-to books that dealt with Freudian theories, the book featured chapters (alternately written by Thurber and White) that delved into pseudo-sexual conditions such as “Frigidity in Men” — the title of a chapter by White excerpted in the Sept. 28, 1929 issue of The New Yorker…

Expanding on the condition known as “recessive knee,” White coined the term “Fuller’s retort,” and claimed it was “now a common phrase in the realm of psychotherapy”…

No other editor besides founder Harold Ross did more to give The New Yorker its shape and voice than Katharine Angell, who recommended to Ross the hiring of both White and Thurber. It is worth noting that White would marry Angell in the same month, November 1929, as the publication of Is Sex Necessary? In their case, sex was necessary, as Katharine would give birth to their son, Joel White, the following year.

* * *

A New Rabbit Hole

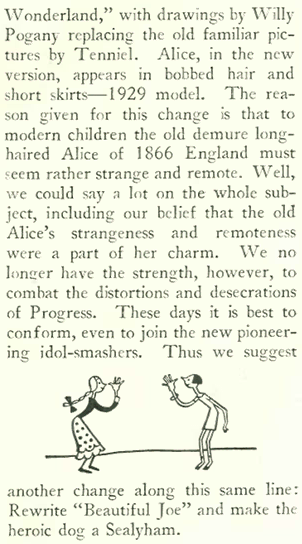

In other news from the world of publishing, “The Talk of the Town” (also largely a product of Thurber and White) noted the publication of a new edition of Alice in Wonderland that featured a re-drawn Alice with bobbed hair and the slender profile of a 1920s flapper. White mused:

* * *

Rise of the Boob Tube

Also in “Talk,” it was reported that the BBC would be putting television on the air “five times a week for a half an hour.” The broadcasts, on a single channel, featured speeches, comic monologues and popular songs. The technology did not allow sound and image to be transmitted together, so “viewers” (there were only a handful of sets) first heard each piece in audio, followed by a mute moving image:

* * *

Mutt & Jeff & Peggy

This odd little item in “Talk” focused on the literary interests of Peggy Hopkins Joyce, an actress and dancer best known for her lavish lifestyle and multiple marriages and affairs. She was a Kardashian of her day — famous for being famous. Despite her flamboyant ways, Joyce seemed to have some rather pedestrian tastes, at least when it came to her reading pleasure…

* * *

Ring Cycle

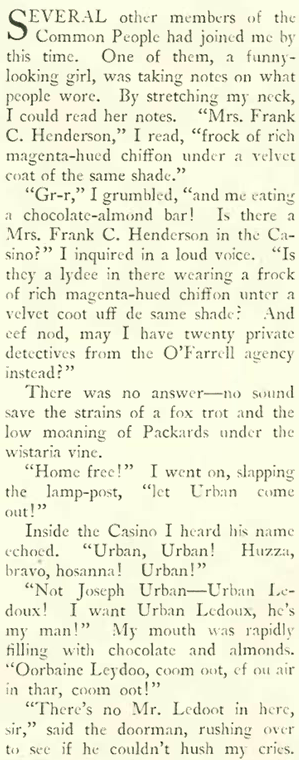

Ring Lardner contributed a casual titled “Large Coffee,” in which he checks into a hotel to escape life’s distractions and get some writing done. The piece consisted of diary entries largely concerned with Lardner’s inability to get a proper order of coffee. He began with an editor’s note that described how his corpse was found in the room, along with the diary. Some excerpts:

* * *

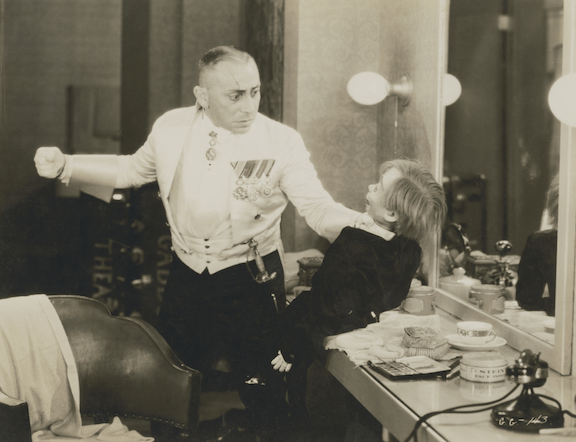

Master of the Screwball

Preston Sturges (1898-1959) was known for taking the screwball comedy and turning into something more than a simple farce. Reviewer Robert Benchley saw the potential in this young Broadway producer, whose second play, Strictly Dishonorable, opened to great acclaim:

* * *

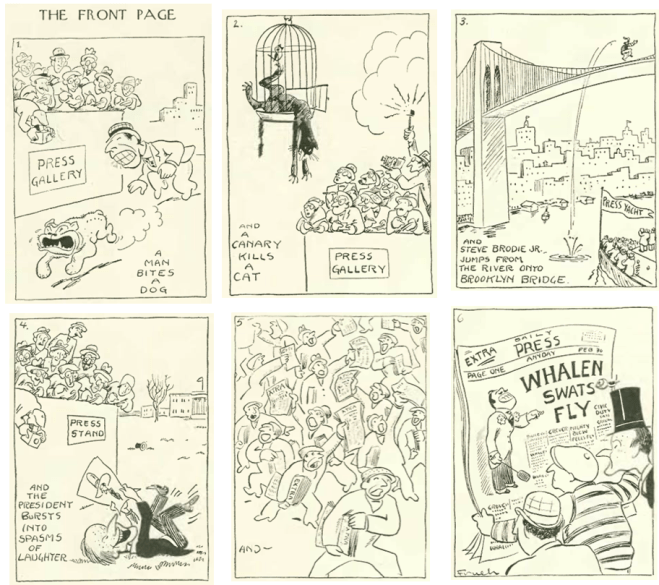

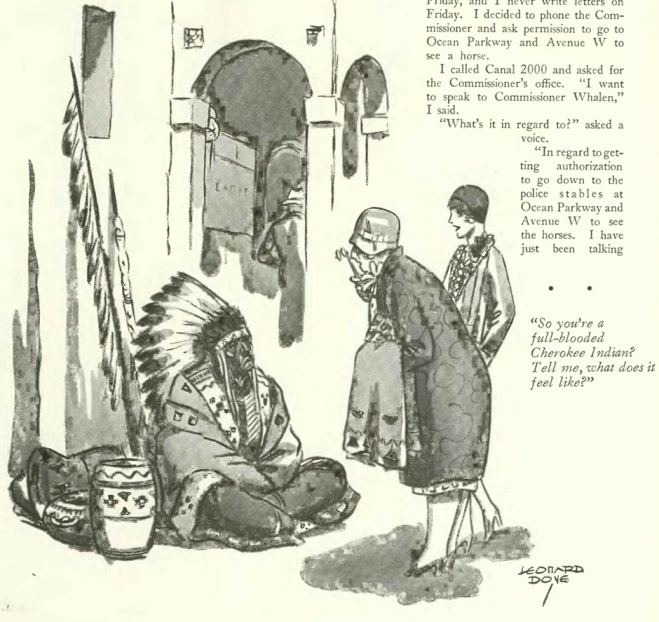

Have No Fear

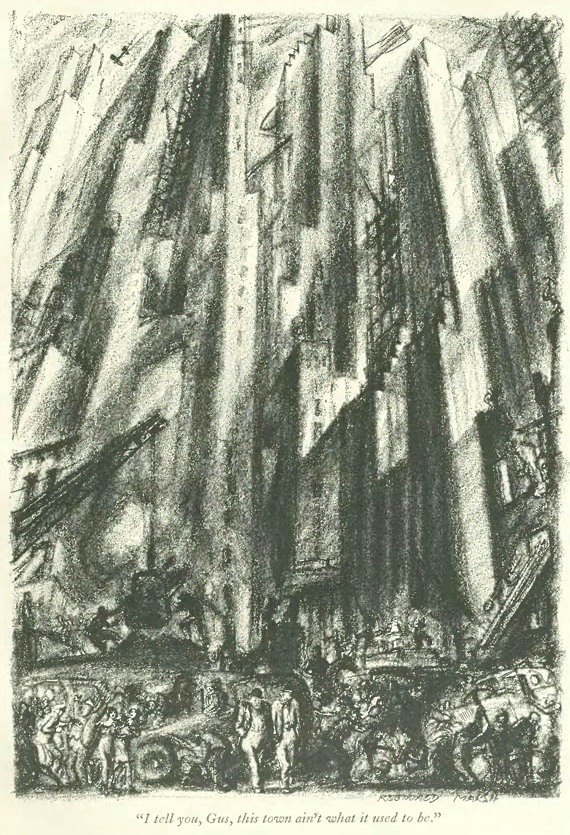

Morris Markey (1899-1950) often took on the lurid and sensationalist reporting of his day in a column he established at The New Yorker titled “Reporter at Large.” In his Sept. 28 column titled “Fear, Inc.” Markey chided everyone from the newspapers and Hollywood to the headline-grabbing NYC Police Commissioner Grover Whalen, and painted a picture of organized crime that was less violent and glamorous, and a lot more mundane…

Markey suggested that rather than screeching tires and blazing Tommy guns, most of the crime in the city was just the humdrum of making money…

Sadly, Markey himself would meet a violent end, dying of a gunshot wound at the age of 51. It is unclear whether it was self-inflicted.

* * *

The Last Laugh

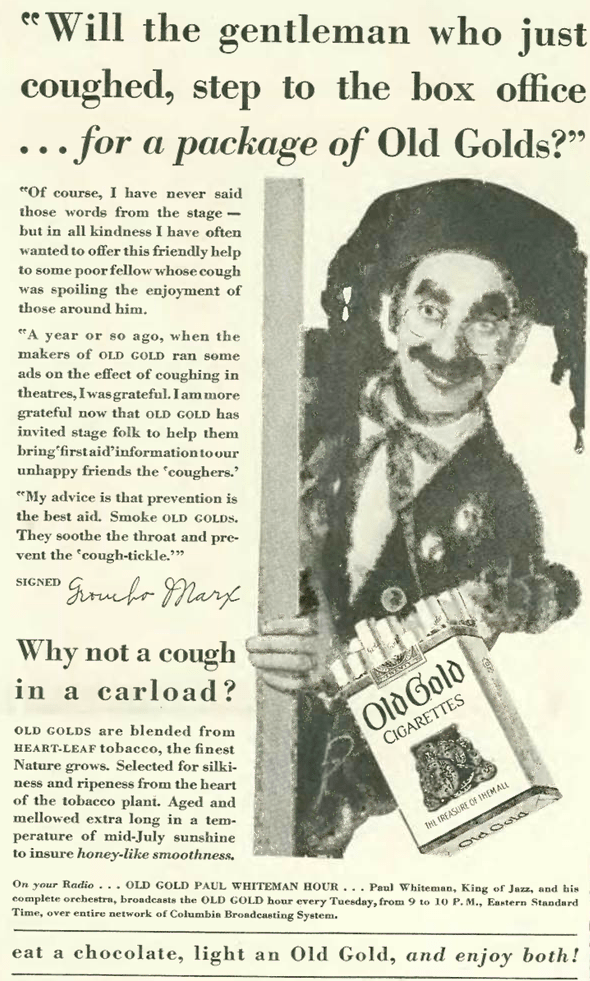

The year 1929 saw the passing of Minnie Marx, the beloved mother of the Marx Brothers comedy troupe. Alexander Woollcott offered this tribute in his “Shouts and Murmurs” column…

* * *

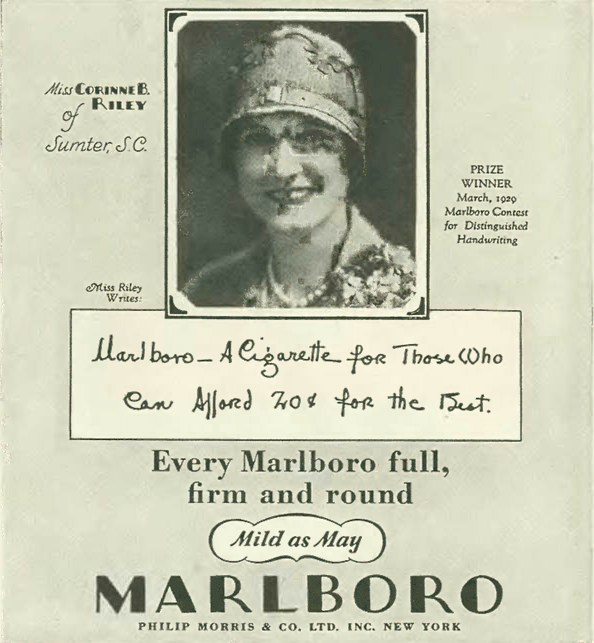

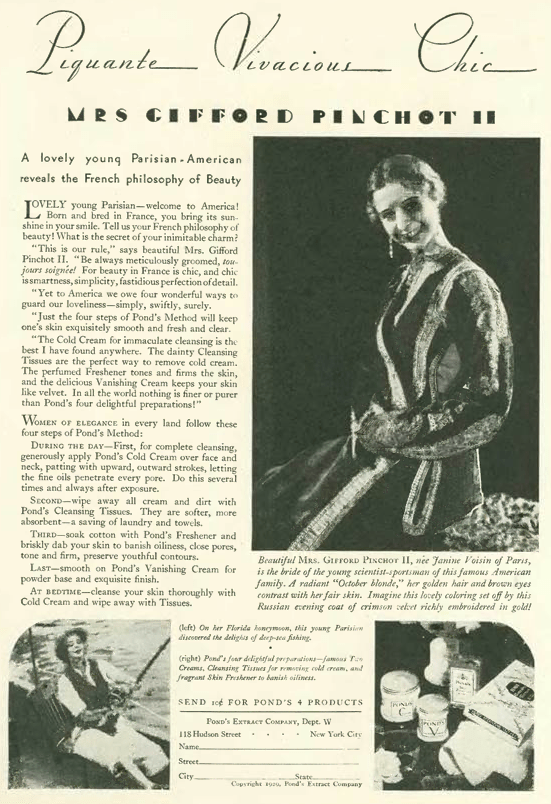

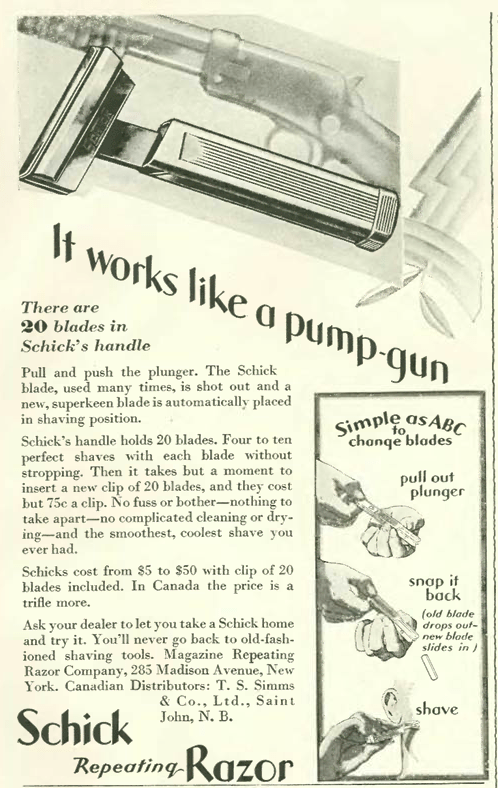

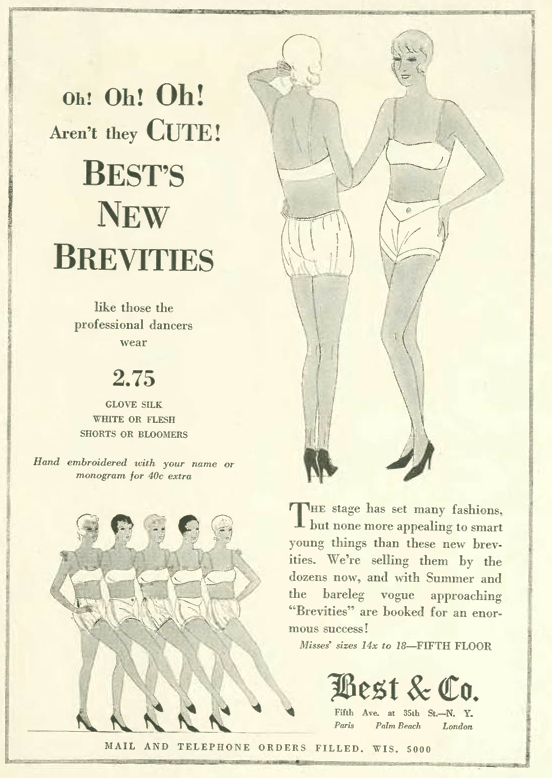

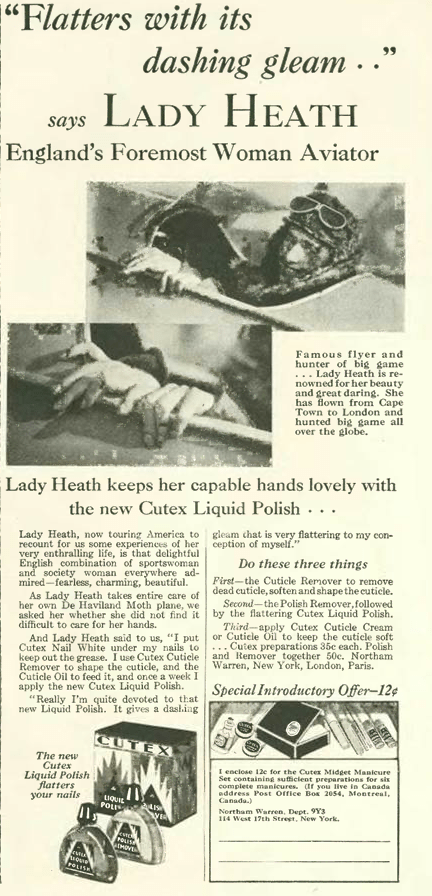

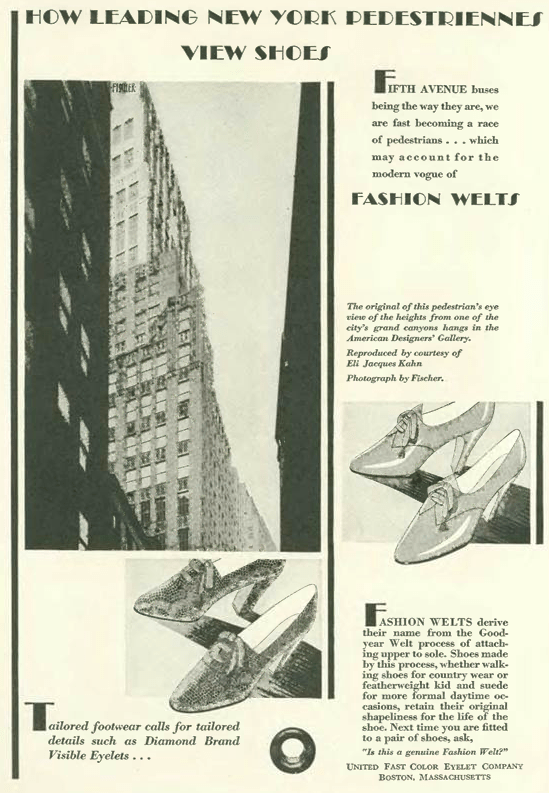

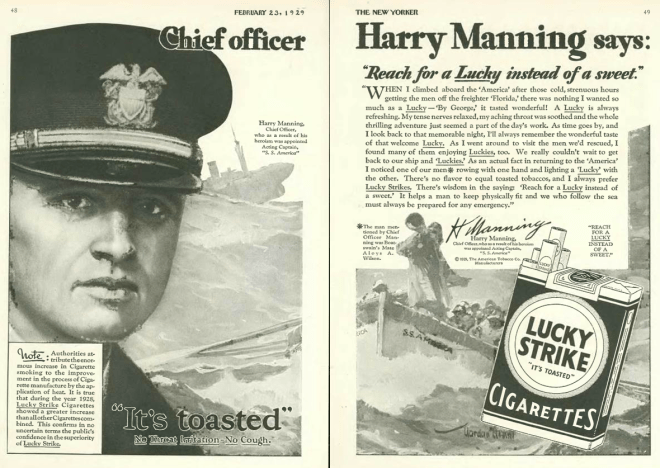

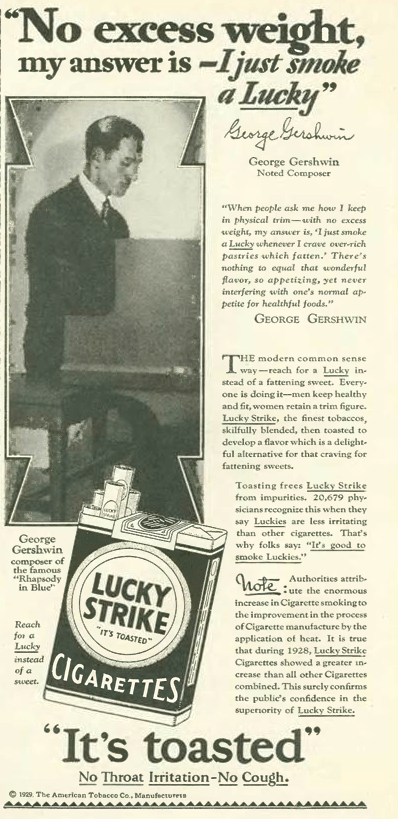

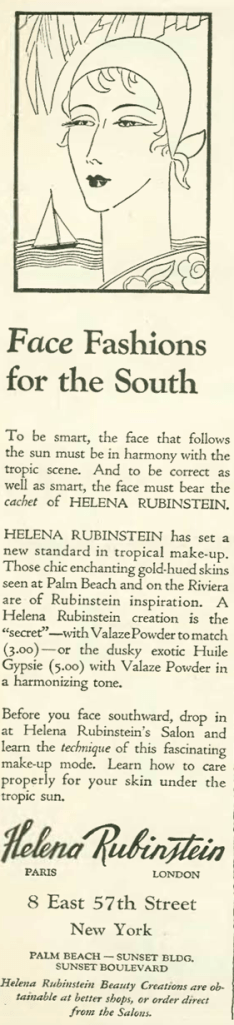

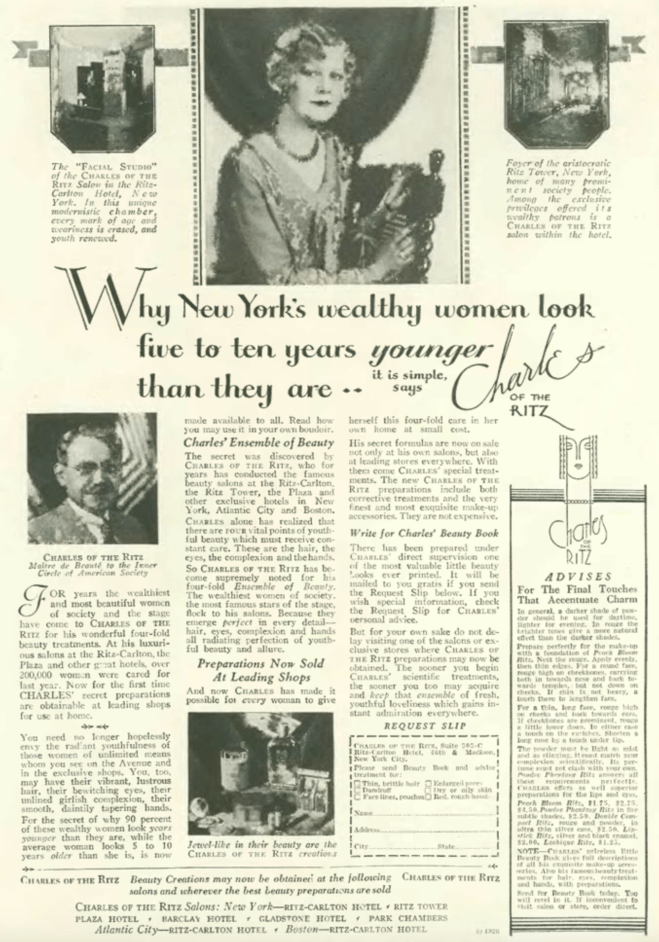

From Our Advertisers

Harper’s Bazar began weekly publication in 1867, catering to women in the middle and upper classes. The magazine was a frequent advertiser in the upstart New Yorker, no doubt perceiving a considerable overlap among its readers. This full page ad in the Sept. 28 issue of the New Yorker featured a column by the Bazar’s Paris fashion correspondent, Marjorie Howard…

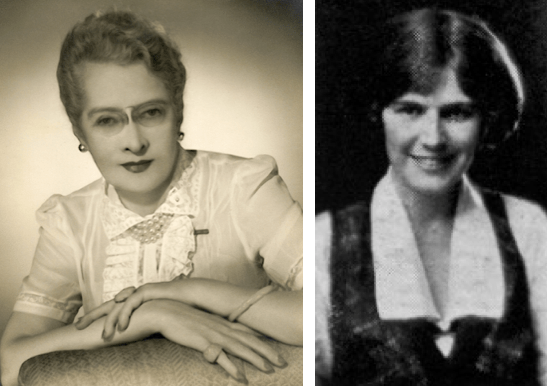

…no doubt The New Yorker’s own fashion editor, Lois Long (1901-1974), read her rival’s column with great interest, and, like the magazine she wrote for, Long was the young upstart compared to the veteran Howard (1878-1958). However, according to future New Yorker editor William Shawn, Long was the superior writer. Upon Long’s death in 1974, Shawn said “Lois Long invented fashion criticism,” adding that she “was the first American fashion critic to approach fashion as an art and to criticize women’s clothes with independence, intelligence, humor and literary style.” Here is a brief excerpt from Long’s fashion column, “On and Off the Avenue,” in the Sept. 28 issue…

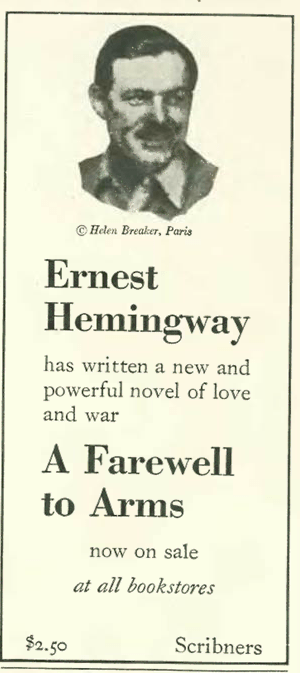

…looking at some of the ads from the magazine’s back pages, here’s one from Scribner’s announcing the publication of A Farewell to Arms (a first edition for only $2.50)…

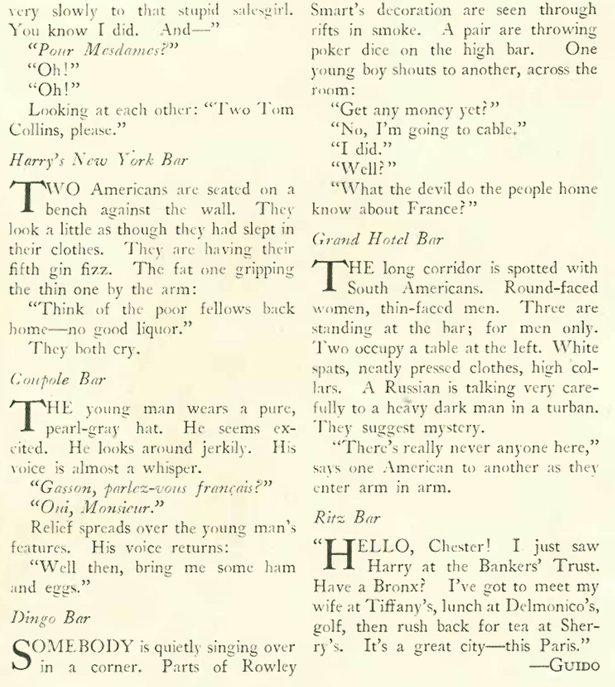

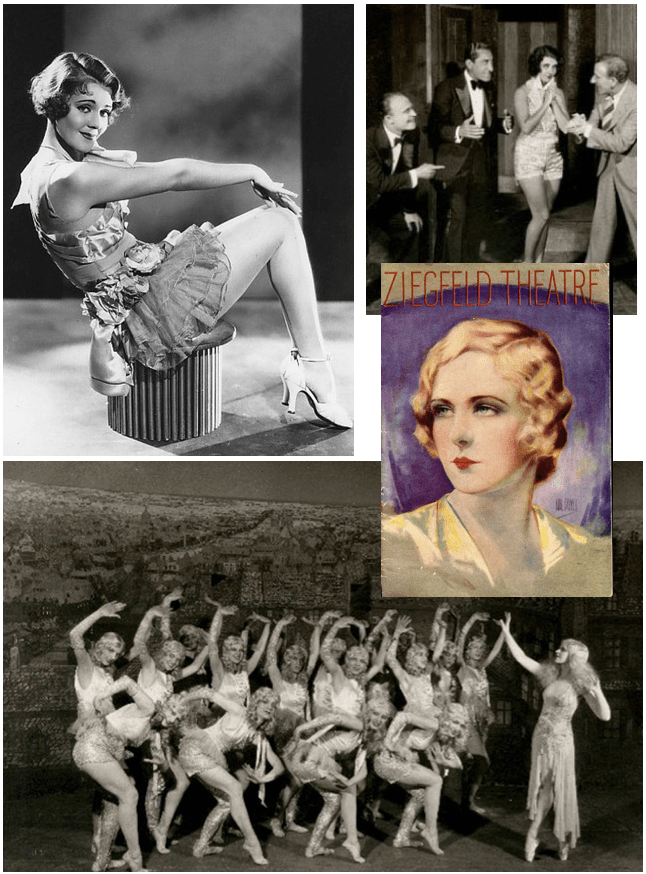

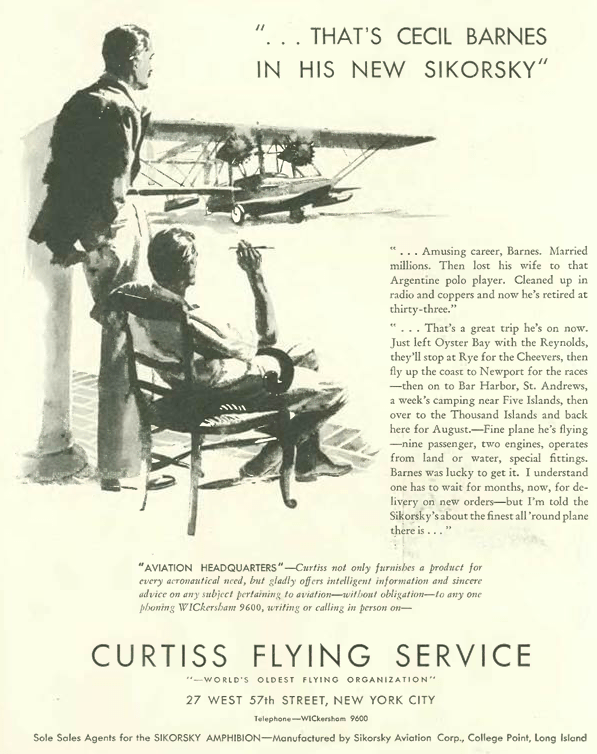

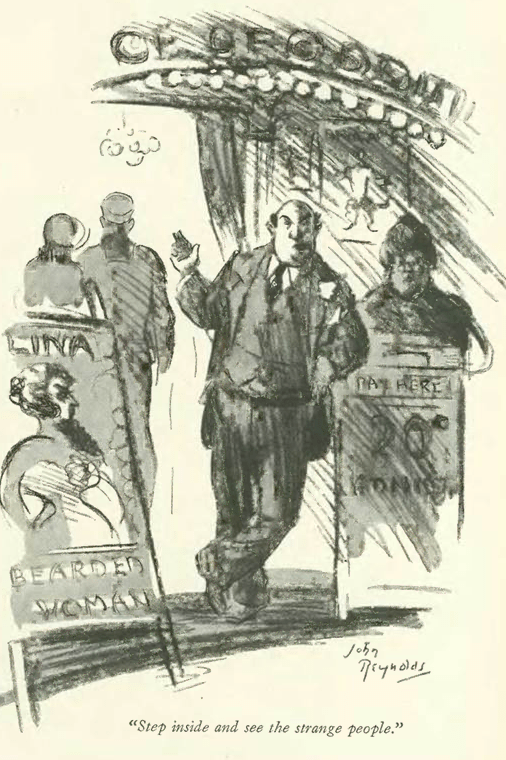

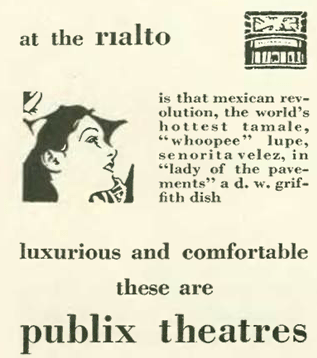

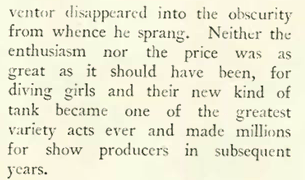

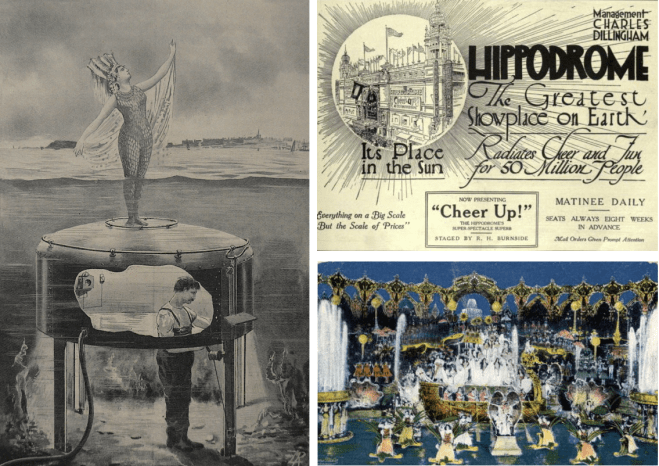

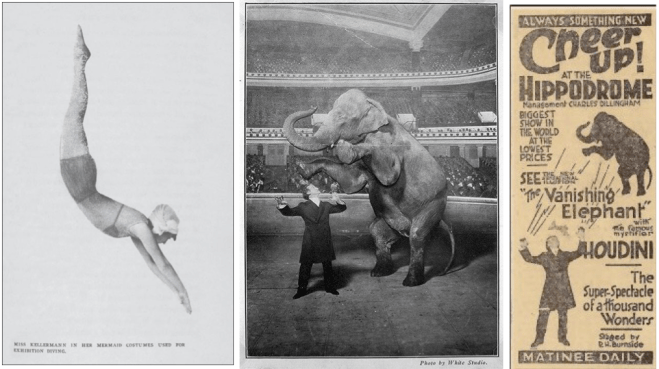

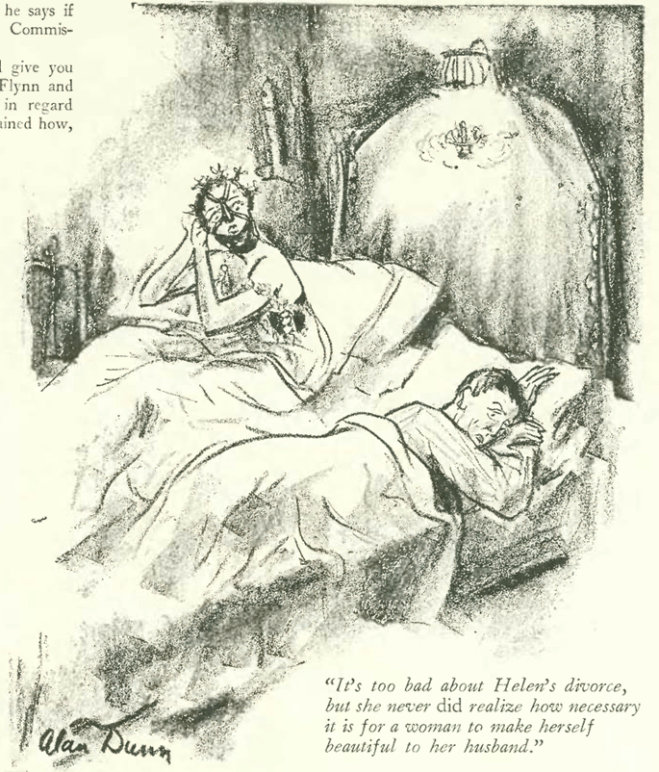

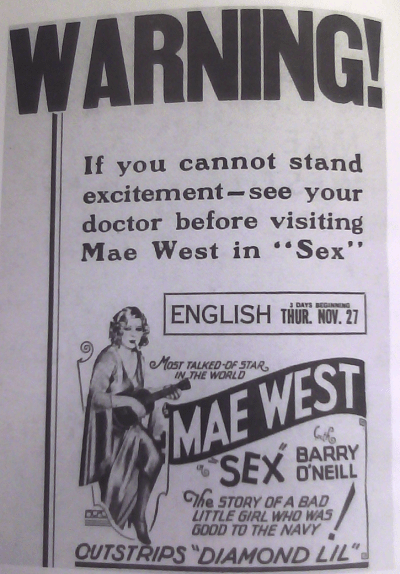

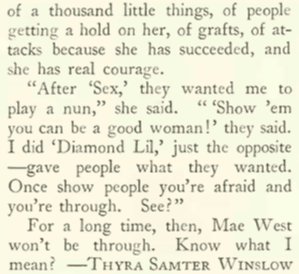

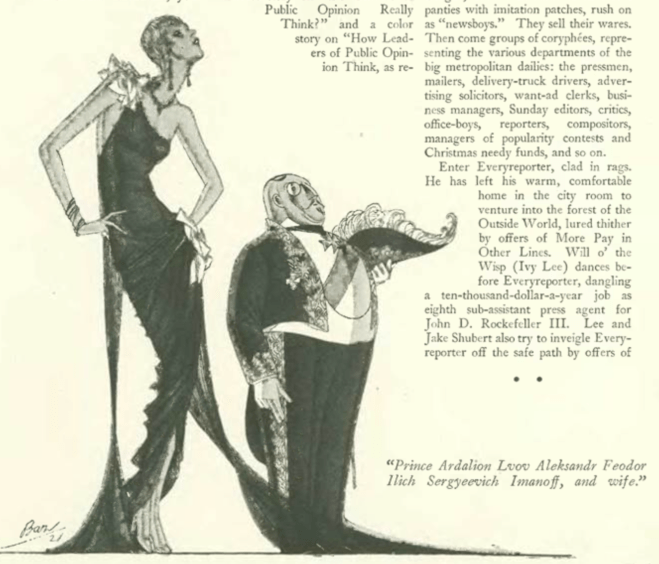

…the back pages of The New Yorker near the theater section were filled with signature ads promoting various entertainments…

…this ad from Kargère referenced an exchange from Oscar Wilde’s The Picture Of Dorian Gray: “They say that when good Americans die they go to Paris,” chuckled Sir Thomas…” Really! And where do bad Americans go to when they die?” inquired the Duchess. “They go to America,” murmured Lord Henry…

…several ads and filler illustrations from the Sept. 28 issue featured posh folks dressed for fox hunting season, the makers of Spud cigarettes among them…

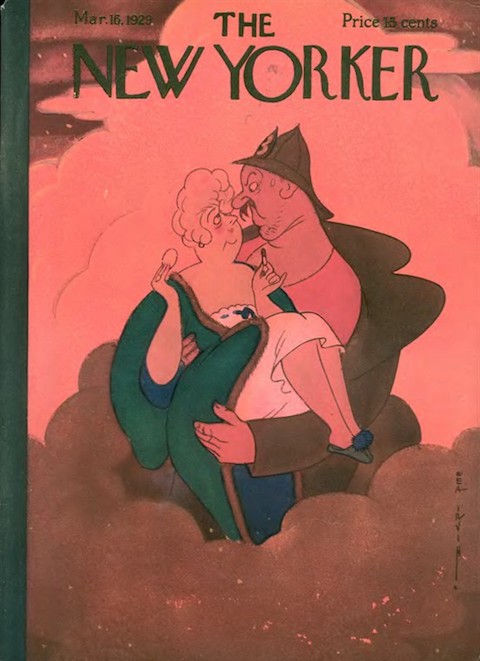

…this ad from Frigidaire featured an illustration by Herbert Roese, whose style at the time somewhat resembled Peter Arno’s…

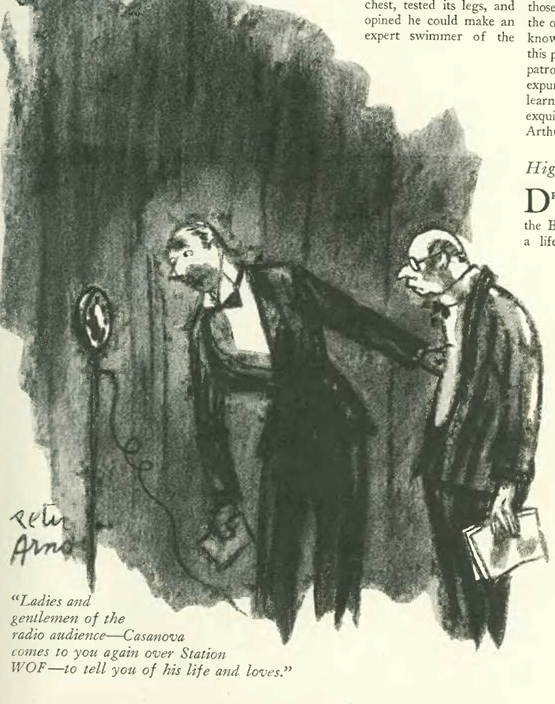

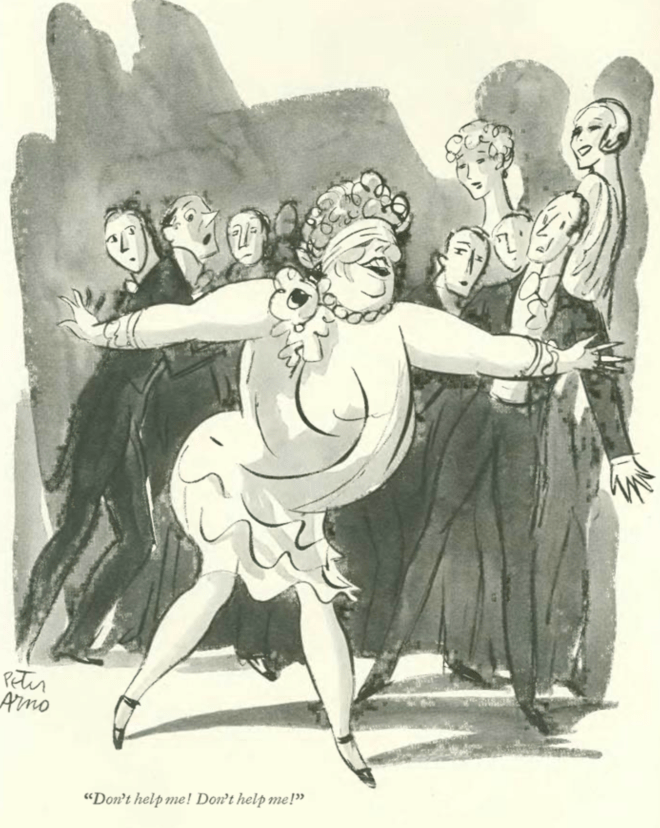

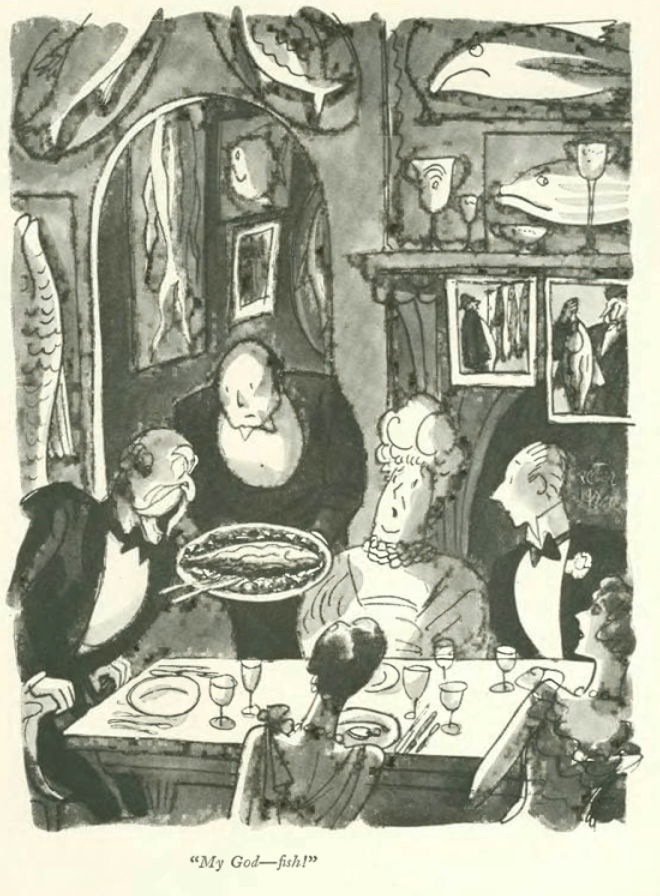

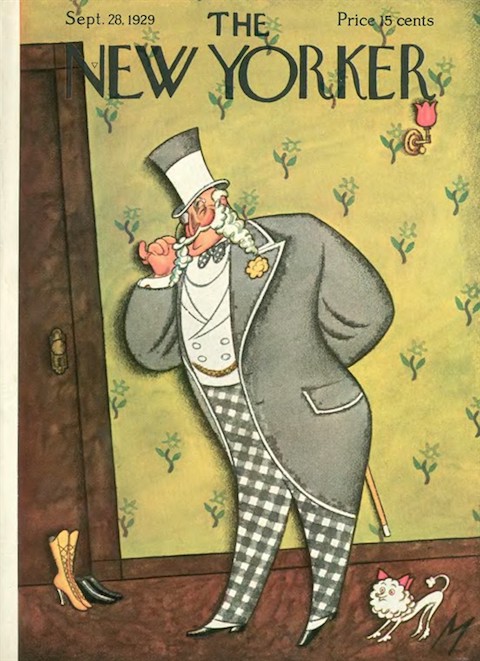

…for comparison, an Arno cartoon from 1930…

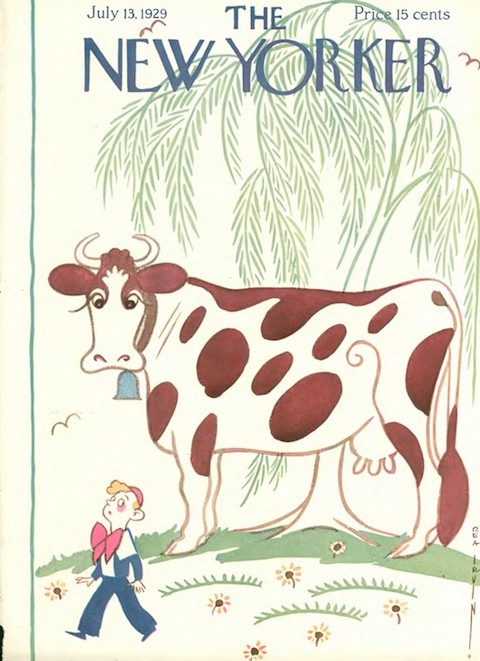

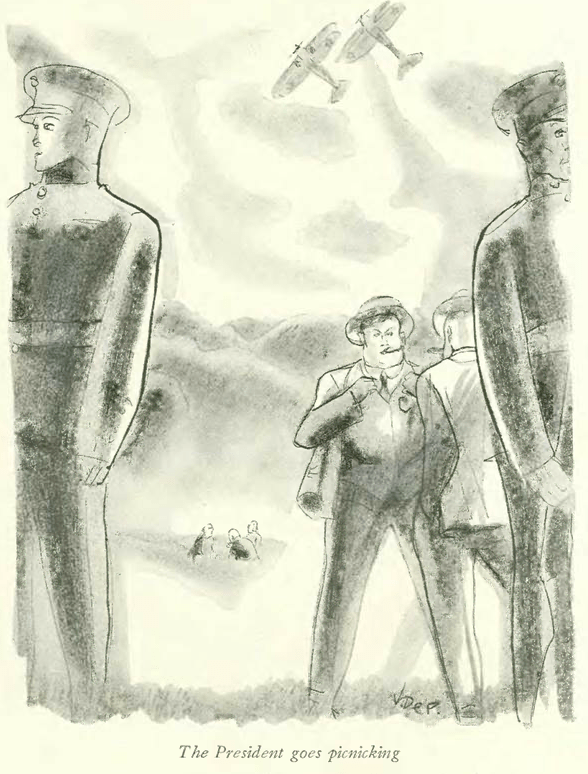

and Arno’s full-page contribution to the Sept. 28 issue…

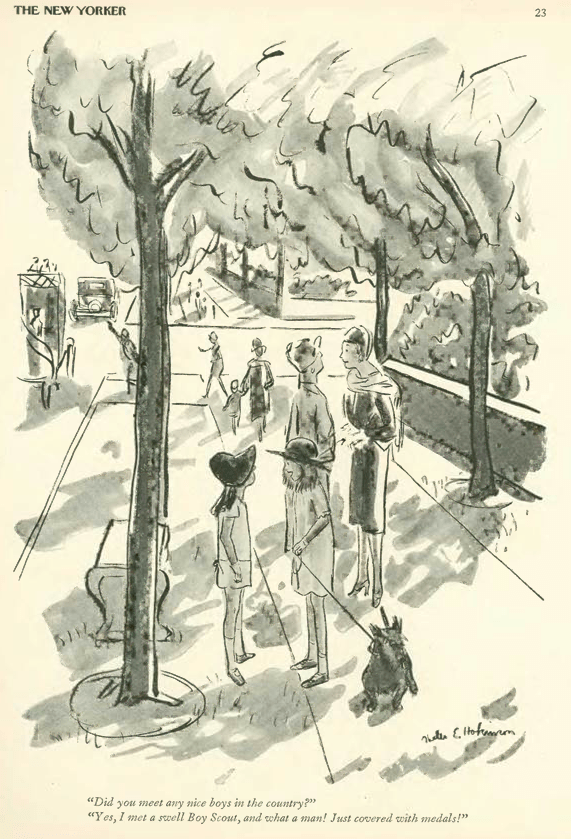

…another artist at The New Yorker who along with Arno often received a full page for her work was Helen Hokinson, here looking in on life at Columbia U…

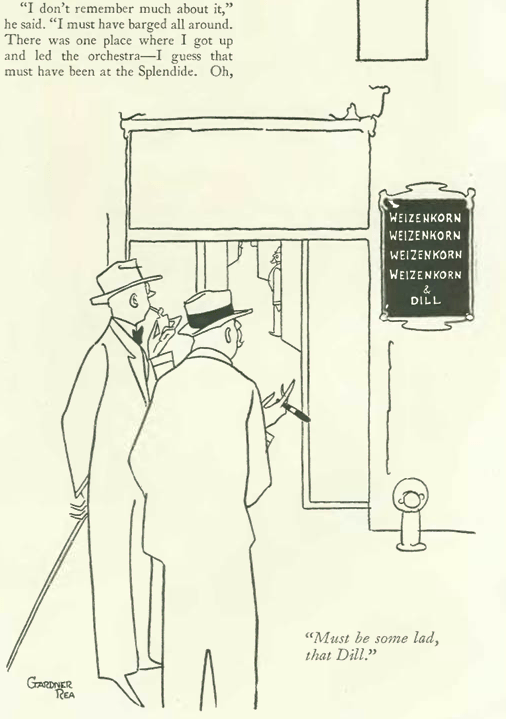

…and there were artists who were lucky to get any space at all, including Kent Starrett, who probably drew on his own experiences at The New Yorker’s front office for this entry…

…and finally, Garrett Price illustrated the challenges of the “house call”…

Next Time: American Royalty…