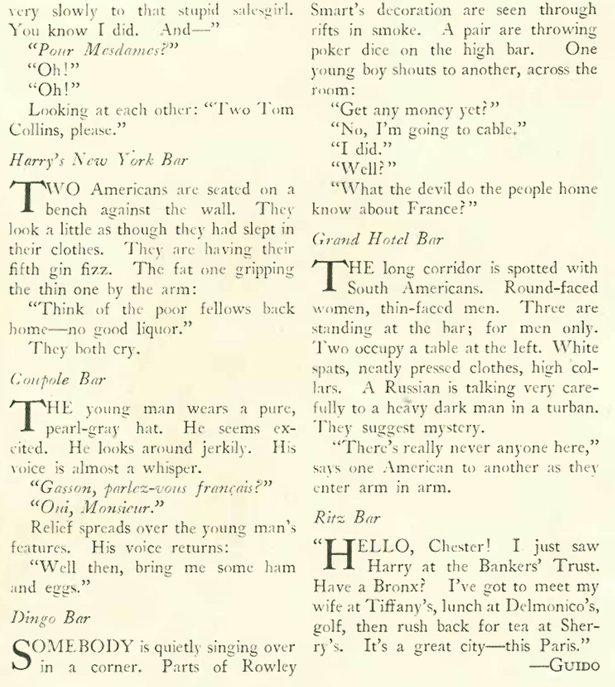

ABOVE: Broadway's As Thousands Cheer (1933) featured evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson (Helen Broderick) trying to persuade Mahatma Gandhi (Clifton Webb) to end his hunger strike and join her act. (NYPL)

Broadway gave Depression audiences a lift with As Thousands Cheer, a revue featuring satirical sketches that skewered the lives and affairs of the rich and famous and served as a precursor to sketch shows like Saturday Night Live.

With a book by Moss Hart and music and lyrics by Irving Berlin, the revue was a big hit, playing for nearly a year on Broadway in its initial run.

Wolcott Gibbs took his turn as Broadway reviewer, and pronounced As Thousands Cheer “the funniest thing in town.”

Not everything was roses in As Thousands Cheer: In a poignant star turn, Ethel Waters sang—at Irving Berlin’s request—his famous tune “Supper Time,” a Black woman’s lament for her lynched husband. The revue was the first Broadway show to give an African-American star (Waters) equal billing with whites, however she was segregated from her co-stars and did not appear in any sketches with them. Her co-stars even refused to bow with her at the curtain call until Berlin intervened. According to the James Kaplan biography Irving Berlin, “The show had a successful tryout at Philadelphia’s Forrest Theatre in early September, although opening night was marred by an ugly incident all too in tune with the times: the stars Clifton Webb, Marilyn Miller, and Helen Broderick refused to take a bow with Ethel Waters. To his everlasting credit, Berlin told the three that of course he would respect their feelings—only in that case there needn’t be any bows at all.

“They took their bows with Waters at the next show.”

* * *

A Final Byline

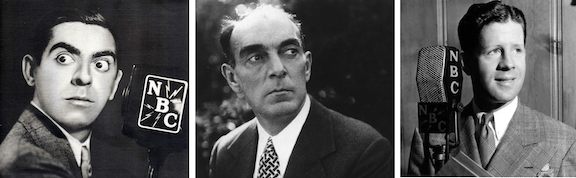

E.B. White opened his column with a tribute to Ring Lardner, who died at age 48 of a heart attack and other complications. In the months before his death Lardner had contributed a number of comical “Over the Waves” radio reviews.

Lardner’s first contribution to The New Yorker came shortly after the magazine’s founding. “The Constant Jay” was published in the April 18, 1925 issue: Readers appreciated his subtle wit, including this oft-quoted gem:

Readers appreciated his subtle wit, including this oft-quoted gem:

“The race is not always to the swift nor the battle to the strong—but that’s the way to bet.”

Lardner also liked to poke fun at himself and his aw-shucks view of things. Here are the opening and closing paragraphs of his final New Yorker contribution, “Odd’s Bodkins:”

* * *

Macy Modernism

As Lewis Mumford observed in his “Skyline” column, Macy’s was the first department store to embrace a modern approach to interior design, but as Marilyn Friedman notes in her book, Making America Modern: Interior Design in the 1930s, Macy’s modernism was a bit toned down to blend into more traditional settings. A case in point was Macy’s 1933 Forward House exhibition, which Mumford described as “a brilliant piece of modern showmanship.”

* * *

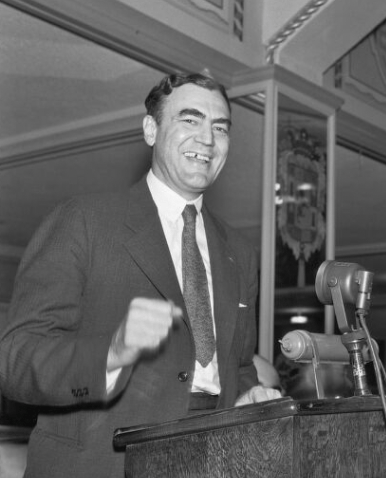

Fishing for Commies

Geoffrey Hellman profiled New York House Rep. Hamilton Fish Jr (1888–1991), a staunch anti-communist perhaps best known for establishing the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery. I feature this brief excerpt mainly for the great caricature by Abe Birnbaum.

* * *

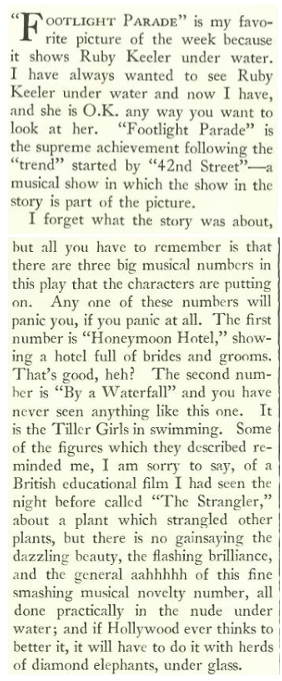

All Wet

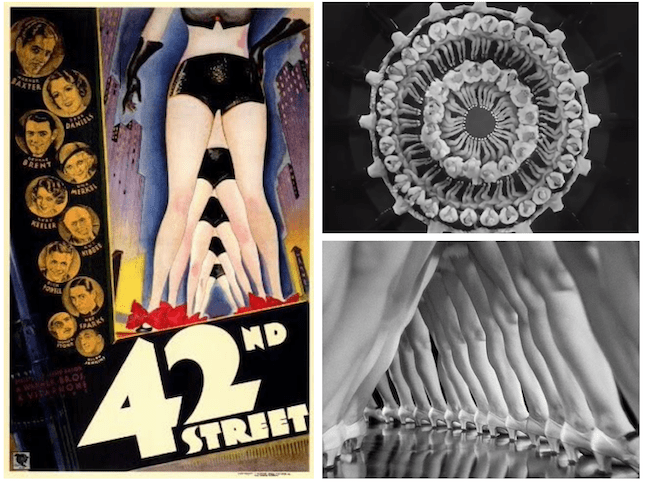

Eleven years before Esther Williams made her first aqua-musical, Ruby Keeler took the dive under Busby Berkeley’s direction in Footlight Parade. E.B. White served as film critic for the Oct. 7 issue, and found Footlight to be a feast for the male gaze, as well as mindless entertainment.

* * *

A Dog’s Life

Doubtless drained from writing The Waves, Virginia Woolf followed up with some historical fiction, namely Flush: A Biography, a book about Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s cocker spaniel. Clifton Fadiman had this to say about the unusual biography:

* * *

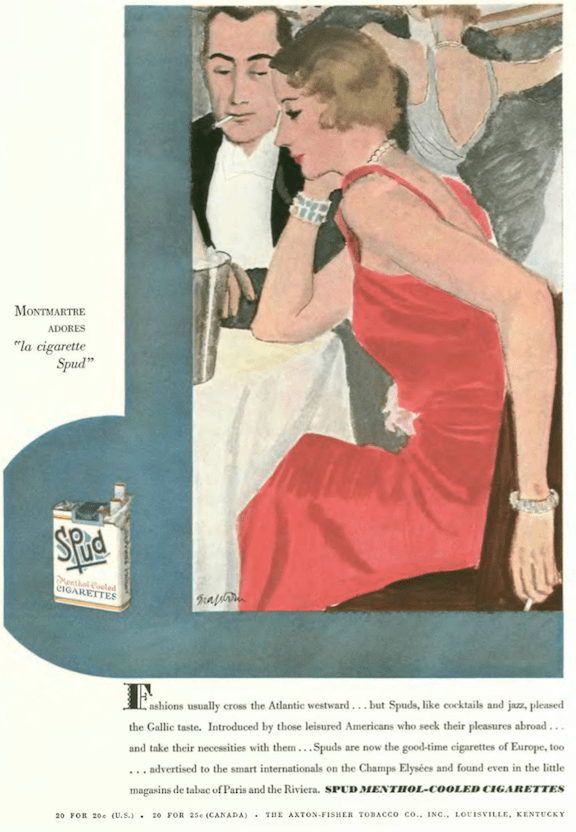

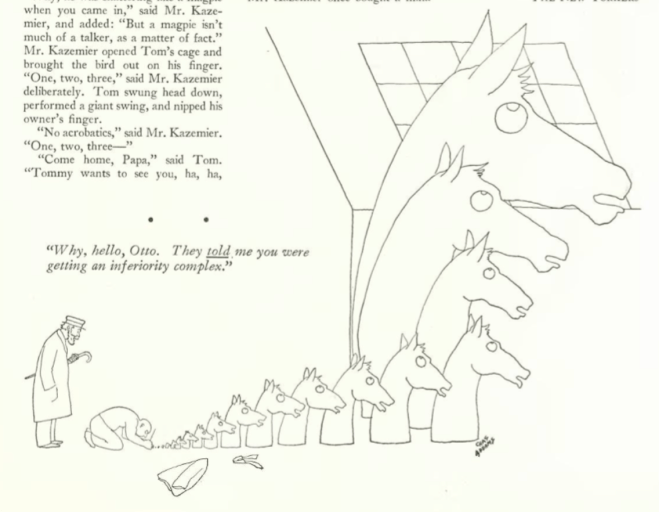

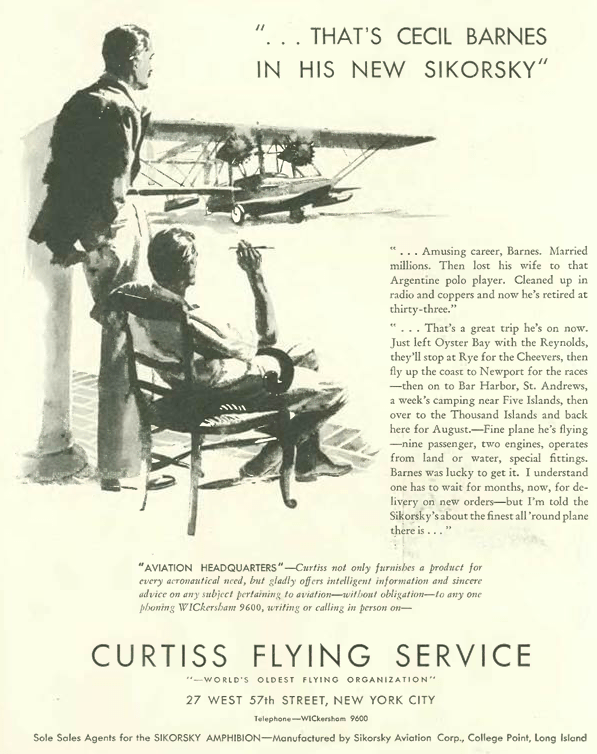

From Our Advertisers

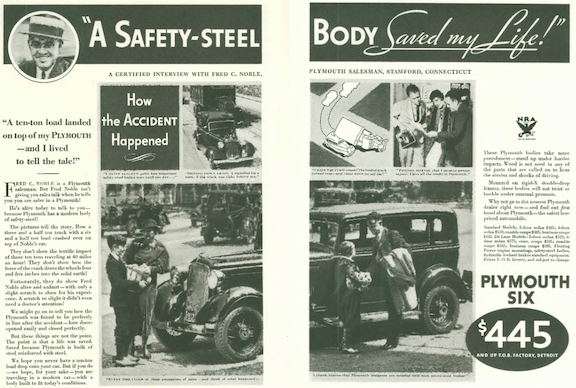

When you market a car for only $445 you aren’t going after the luxury market, but hey, drop a ten-truck truck on this baby and you can live to tell about it…

…with legal beer flooding the market brewers were particularly keen to attract female drinkers of all ages…and apparently social classes…

…a couple of ads from the back pages, the first touting the smart-set writing of columnist and foreign correspondent Alice Hughes for the New York American, and the second an advertisement for Chase & Sanborn coffee, which relayed the story of a marriage on the brink due to stale coffee…

…I include this ad for the heroic scale of the ocean liner, particularly as depicted by the people in the background…

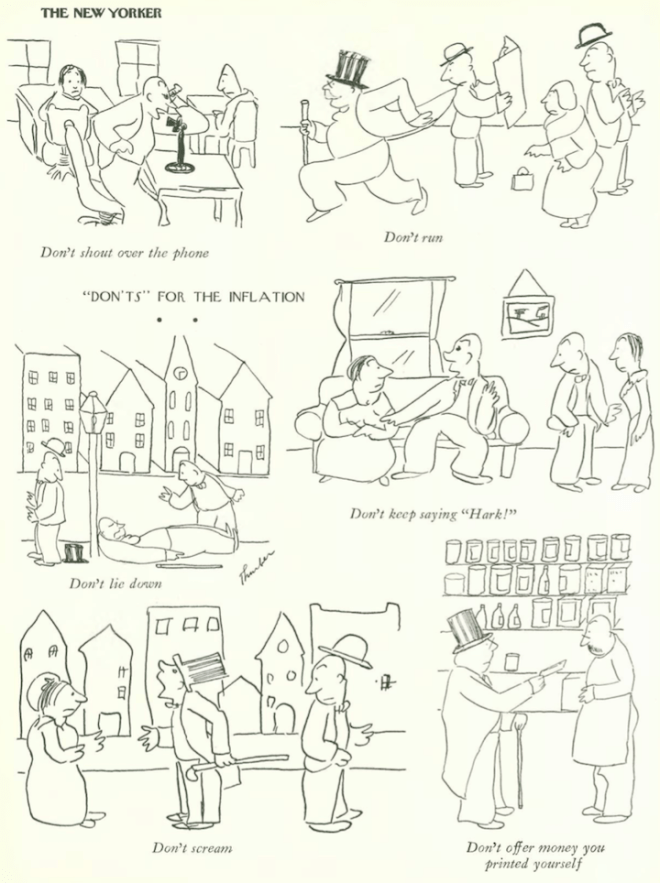

…we bounce on to our cartoons with Otto Soglow’s Little King…

…James Thurber continued to explore the unrest among our domestic youth…

…speaking of America’s youth, this gathering (courtesy Gardner Rea) appeared to have trouble finding some…

…speaking of America’s youth, this gathering (courtesy Gardner Rea) appeared to have trouble finding some…

…Helen Hokinson found fun with flounder…

…Rea Irvin turned the tables on a life-drawing class…

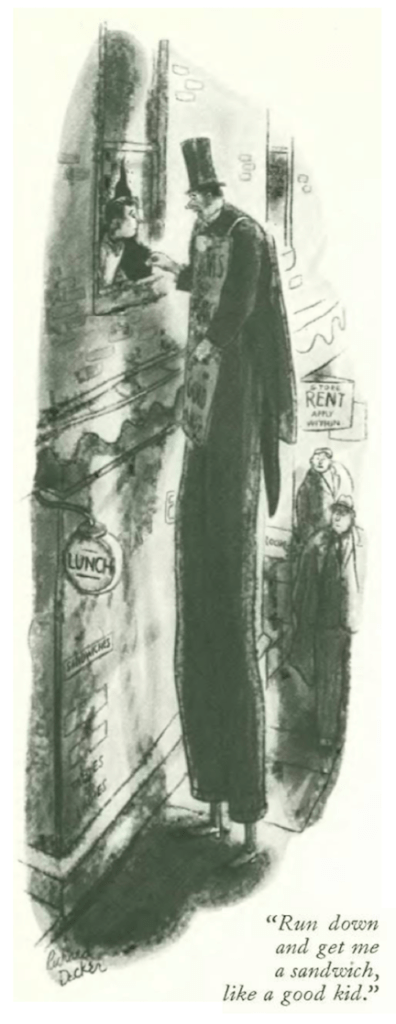

…and we close with Richard Decker, over the moon with a stranded chorine…

…and in a nod to the approaching holiday, imagery from a 1933 Fleischer Studios animated short film, Betty Boop’s Hallowe’en Party…

Next Time: The Wild West…