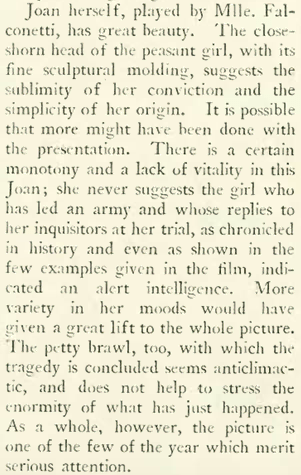

Despite the rise of the professional classes in the 20th century (and their attendant rules for accreditation and licensing) there still existed individuals who practiced at the highest levels with little or no formal training.

Gustav Lindenthal (1850-1935) was a case in point. An Austrian immigrant who designed New York’s Hell Gate Bridge among others had little formal education and no degree in civil engineering. Rather, he learned by working as an assistant on various construction projects and teaching himself mathematics, metallurgy, engineering, hydraulics and other principles of the building profession.

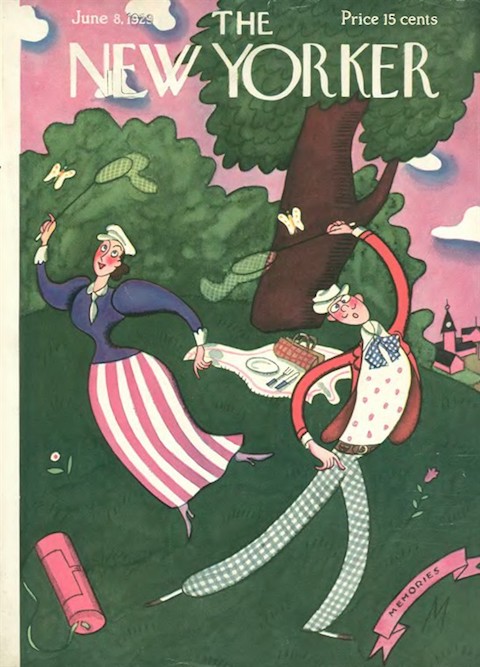

Lindenthal was praised for his innovations in bridge design as well as for his artistic eye, but one project eluded him throughout his career: the largest bridge in the world—a massive double-decker that would span the Hudson River from 57th Street in New York City to Hoboken in New Jersey. The June 8, 1929 “Talk of the Town” checked in on the nearly 80-year-old bridge builder:

A cornerstone for the Hudson bridge was laid in 1895, but a series of bad breaks, including the 1898 Depression and various political setbacks, served to continually delay the project. The New York Tribune anticipated the bridge in its April 28, 1907 edition…

…and three years later the Tribune seemed confident that work was finally underway…

…however by the 1920s the bridge was still a dream. In 1921 Scientific American offered the latest glimpse of Lindenthal’s proposed 57th Street Bridge — a span 6,000 feet in length, with a 200-foot-wide double deck accommodating 24 lanes of traffic and 12 railroad tracks. An artist’s rendering included a massive building, on an arched plinth, positioned over the bridge deck:

The New Yorker suggested that Lindenthal’s legacy was already secure, and with his determination and vigorous constitution, he still might still win the day:

Despite his vigor, Lindenthal would not live to see his dream realized. However, he is remembered for building some of New York’s most iconic bridges, including the Hell Gate and Queensboro:

* * *

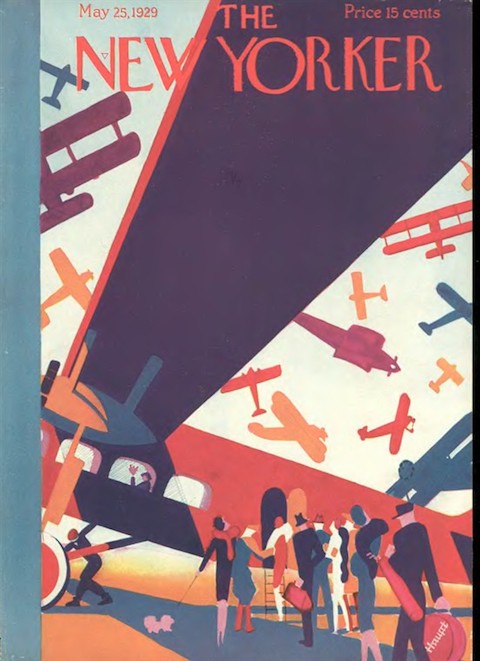

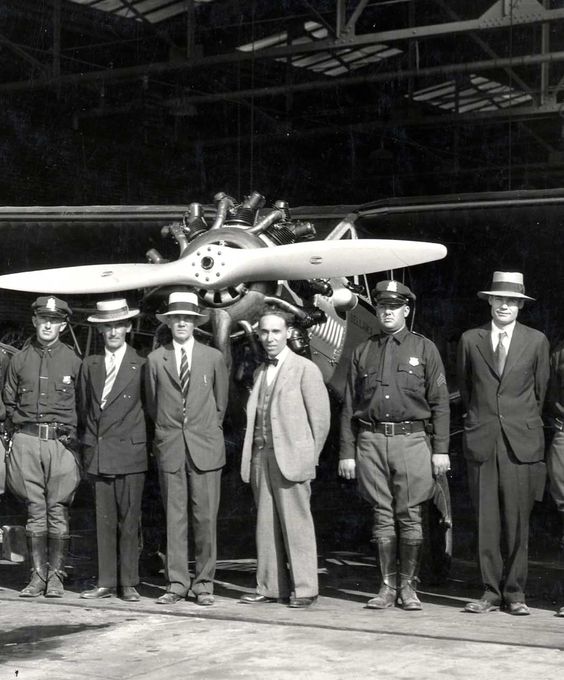

Keeping Up With the Lindberghs

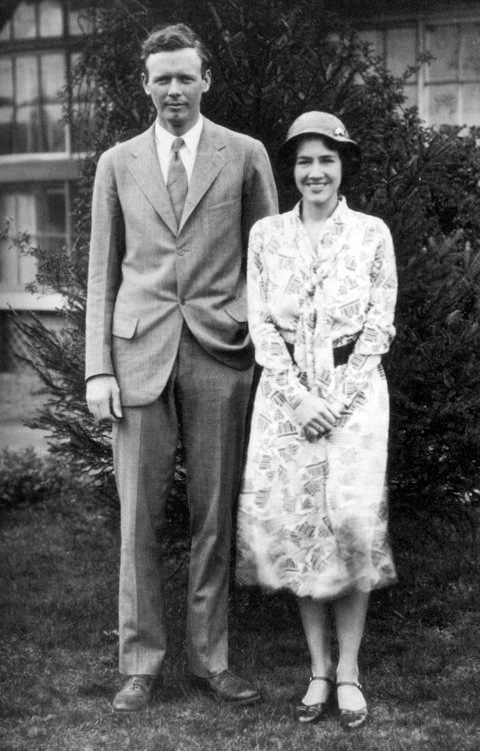

Despite his worldwide fame, Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974) detested the limelight, particularly when it came to his personal life. Writing in the column “The Wayward Press,” humorist Robert Benchley mocked the newspapers for their invasions into the lives of the celebrated, including newlyweds Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh:

Benchley wasn’t buying the newspaper industry’s insistence that the public demanded to know the facts about the flyboy’s nuptials:

* * *

Let the Good Times Roll

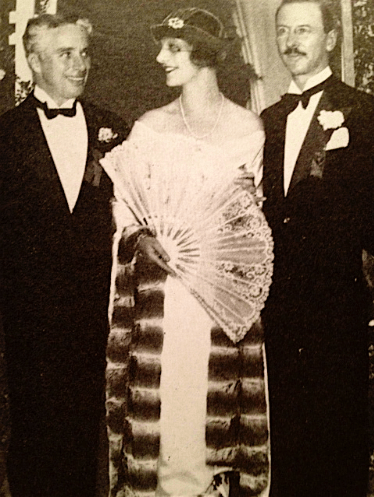

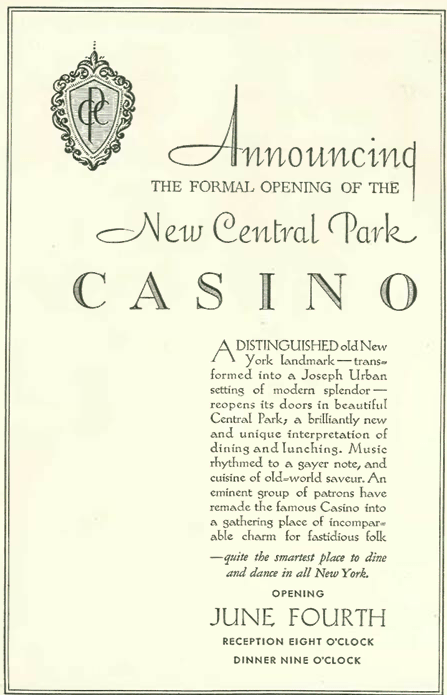

With the newly remodeled Central Park Casino officially christened by Mayor Jimmy Walker and his cronies, The New Yorker’s Lois Long (in “Tables for Two”) decided to pay a visit to see what all the fuss was about:

Long also commented on the declining fortunes of another familiar face of New York nightlife, Texas Guinan, who had fled Manhatten’s smoky speakeasy scene for the bucolic climes of Nassau County…

Long concluded that regardless where one ended up on a summer evening, one should be aware that a shabbier crowd awaited their company:

* * *

Cuba Libre

Now we look at another New Yorker contributor who today is not exactly a household name: Donald Barr Chidsey (1902-1981), an American writer, biographer, historian and novelist best known for his adventure fiction. In this short column he offered some insights into the Cuban drinking scene:

* * *

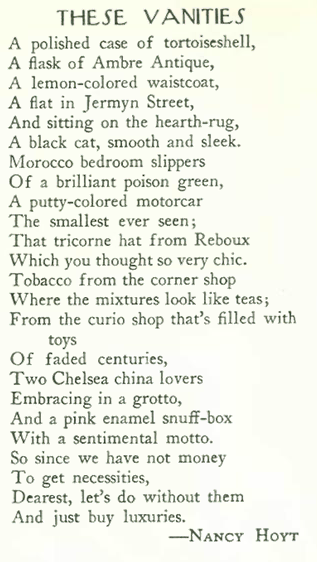

Waxing Poetic

From its very first issue, The New Yorker also published a wide variety of poets, including Nicholas Samstag (1904-1968),who contributed several poems to the magazine in 1928 and 1929. Samstag later went on to a successful career in advertising, and was a close associate of Edward Bernays, considered the father of public relations and propaganda.

A frequent contributor to The New Yorker, writer, poet and critic Mark Van Doren (1894-1972) published more than three dozen poems in the magazine from 1929 to 1972. Here is his first contribution, in the June 8, 1929 issue:

Van Doren’s last contribution to The New Yorker was published on Nov. 18, 1972, less than a month before his death. It was appropriately titled “Good Riddance”…

* * *

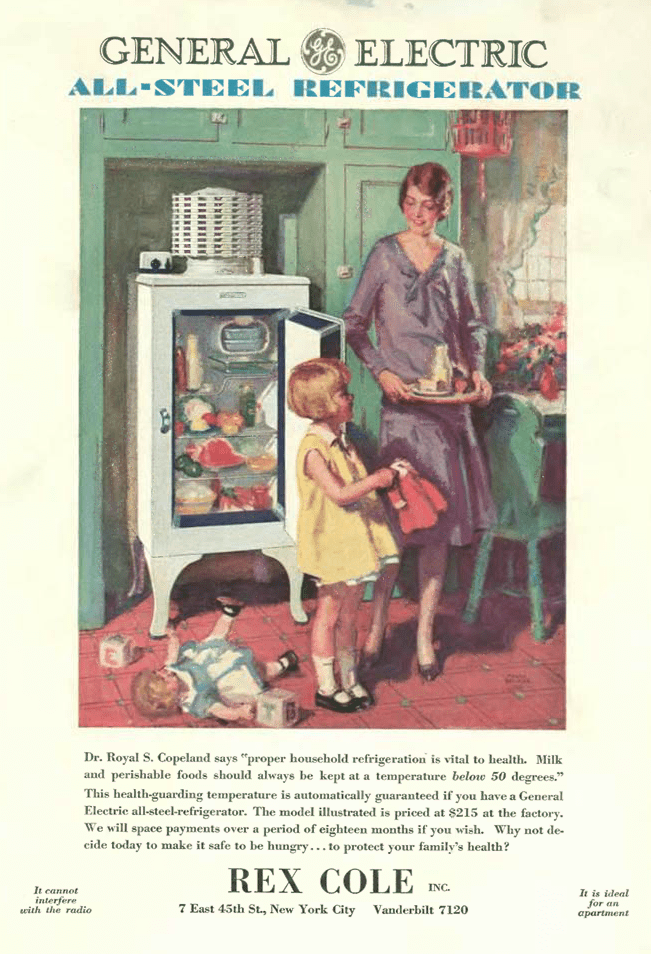

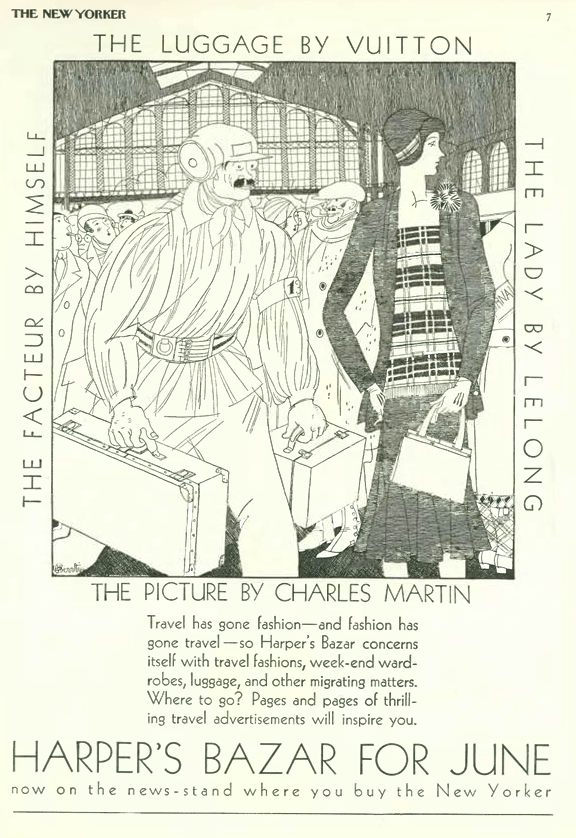

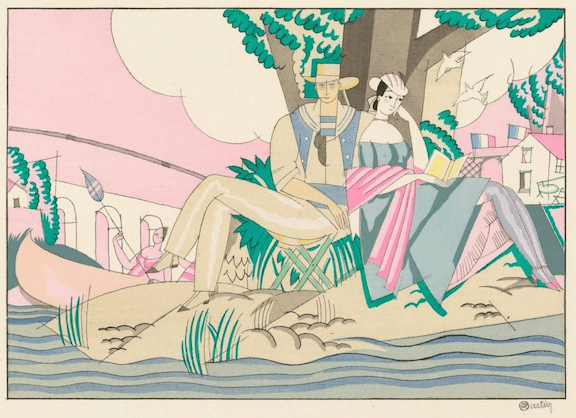

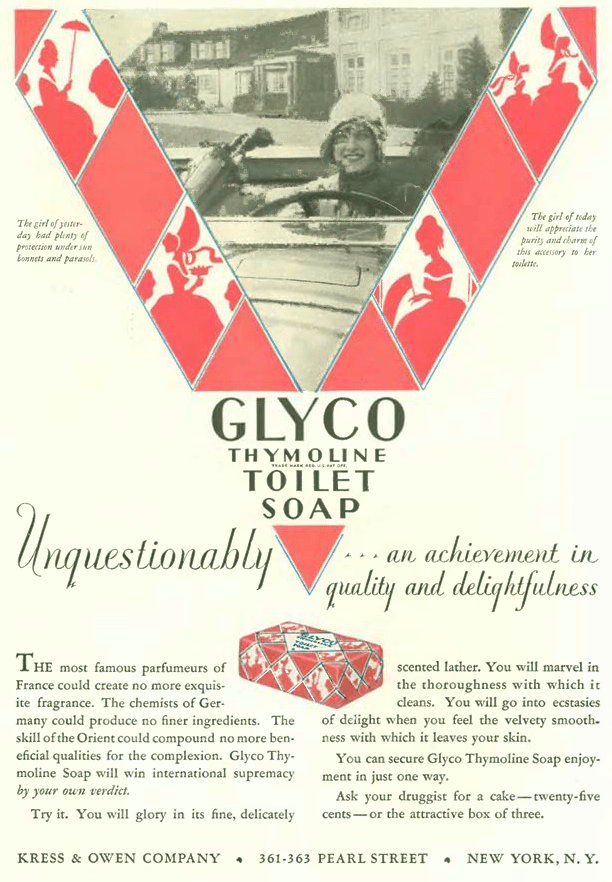

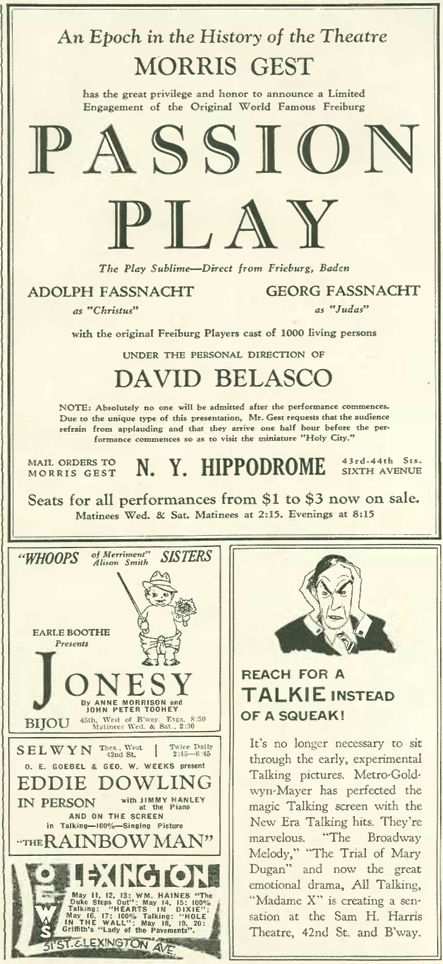

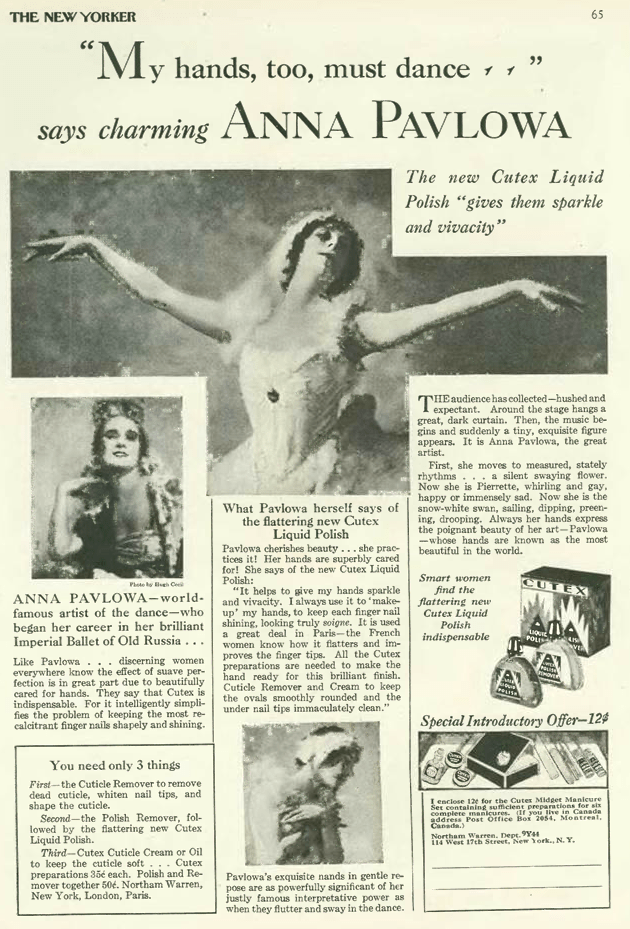

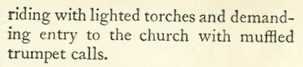

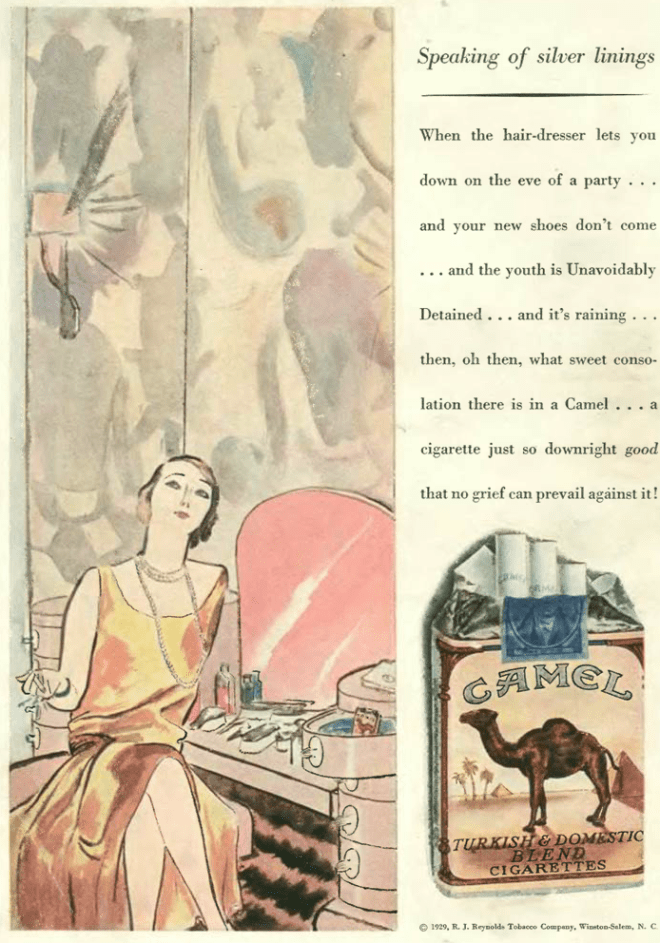

From Our Advertisers

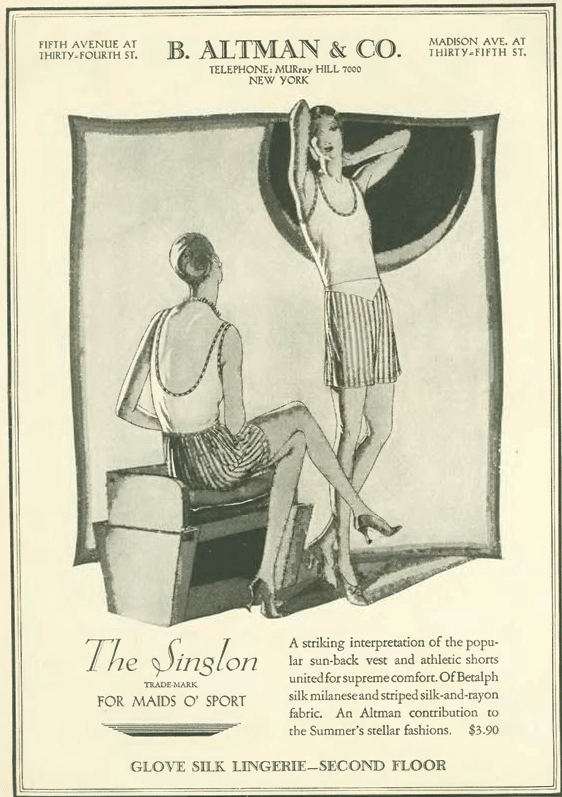

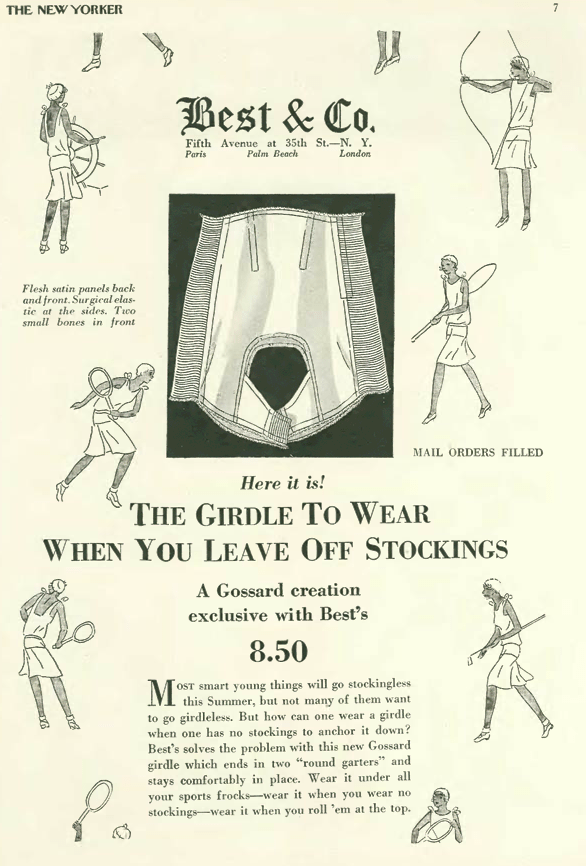

As summer approached some distinct themes emerged in ads aimed at female consumers. Here is a collection of ads from the June 8 issue that capitalized on the new tanning craze of the late 1920s…

…and another big craze of the 1920s, the permanent wave, seemed to be a necessity as summer approached…

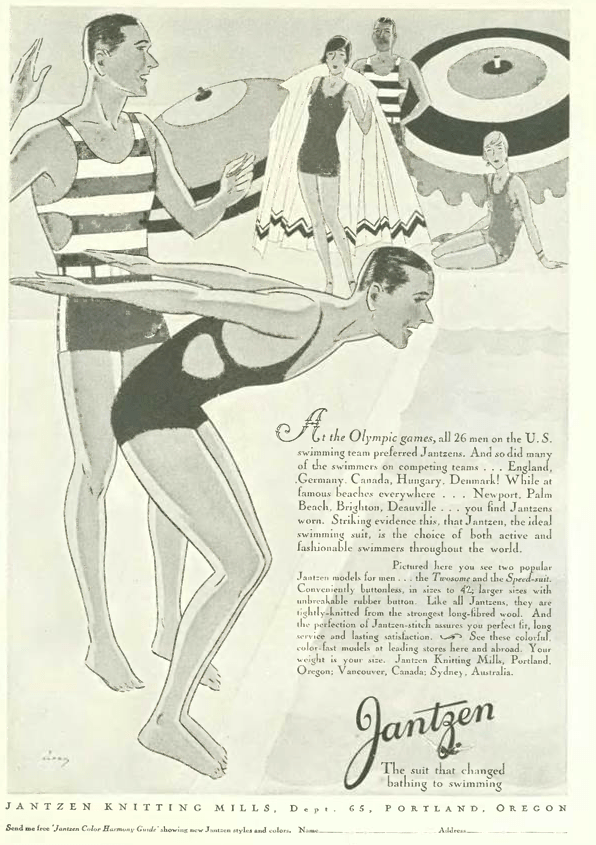

…as for the gents, check out this new line of Jantzen swimwear modeled by what appear to be identical twins…

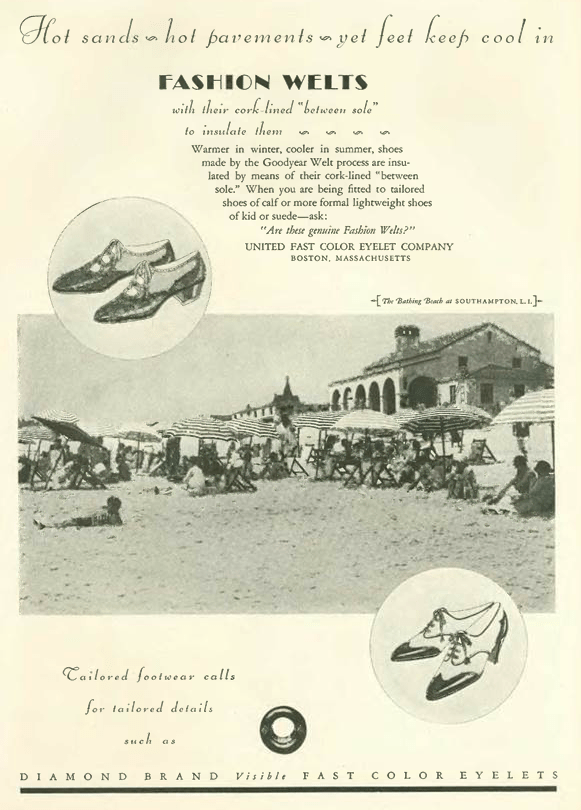

…and when you’re out of the water, a pair of “fashion welts” were all the rage for tip-toeing across the hot sands of Southampton…

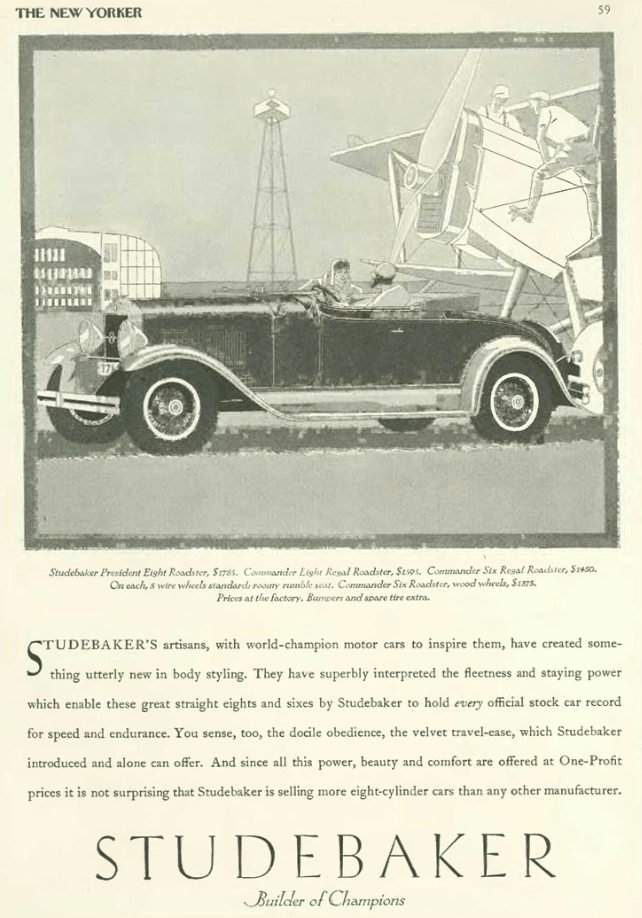

…this ad from B. Altman depicted two women clad for “open motoring” (not sure how those long, lithe figures will fit into that tiny rumble seat)…

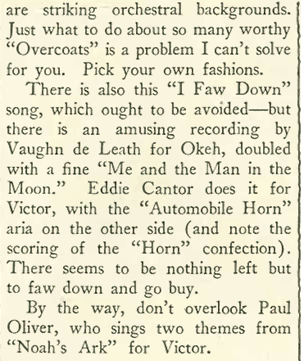

…for a less dusty mode of transportation, you could hop aboard The Broadway Limited for a quick 20-hour jaunt to Chicago…

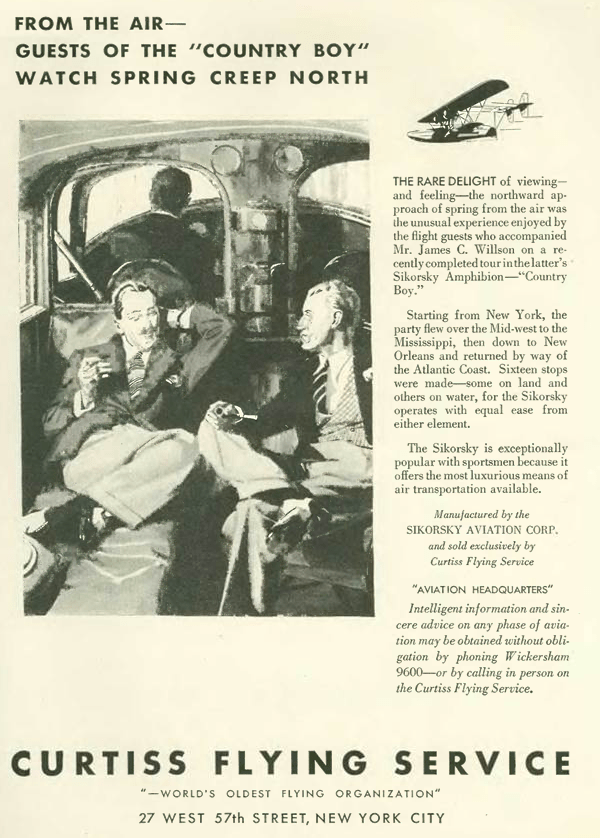

…or better yet, have a relaxing smoke with one of your chums aboard a Sikorsky seaplane…

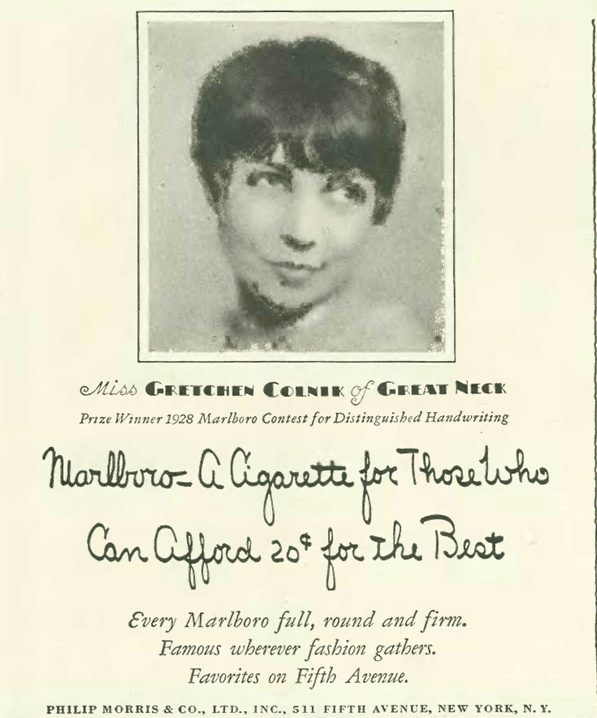

…our cigarette ad for this week comes from Philip Morris, makers of Marlboro, who once again exploited the nation’s youth with a bogus handwriting contest that doubled as a product endorsement…

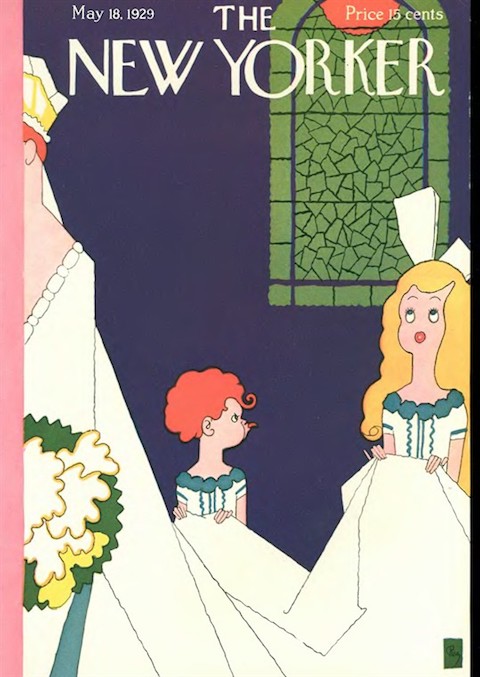

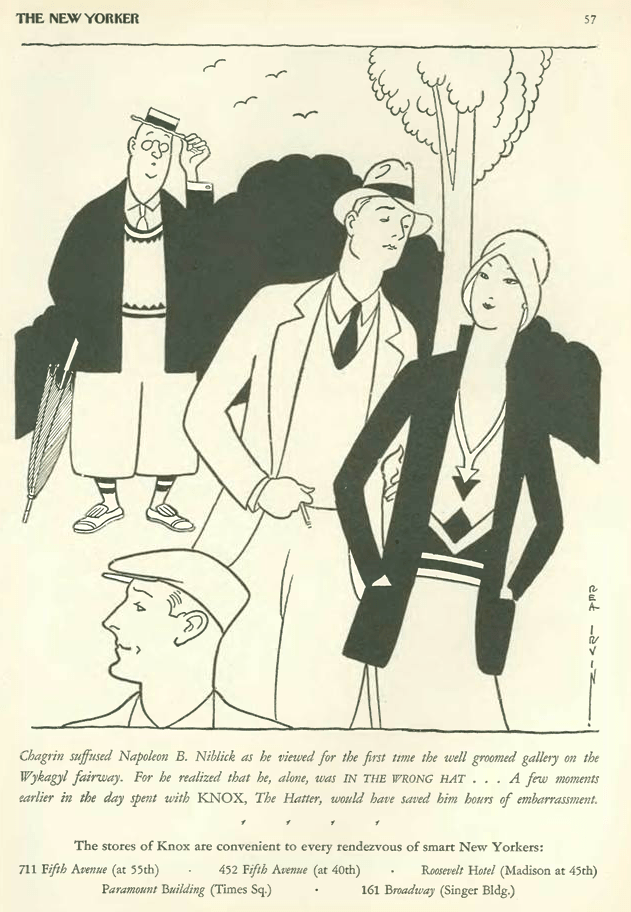

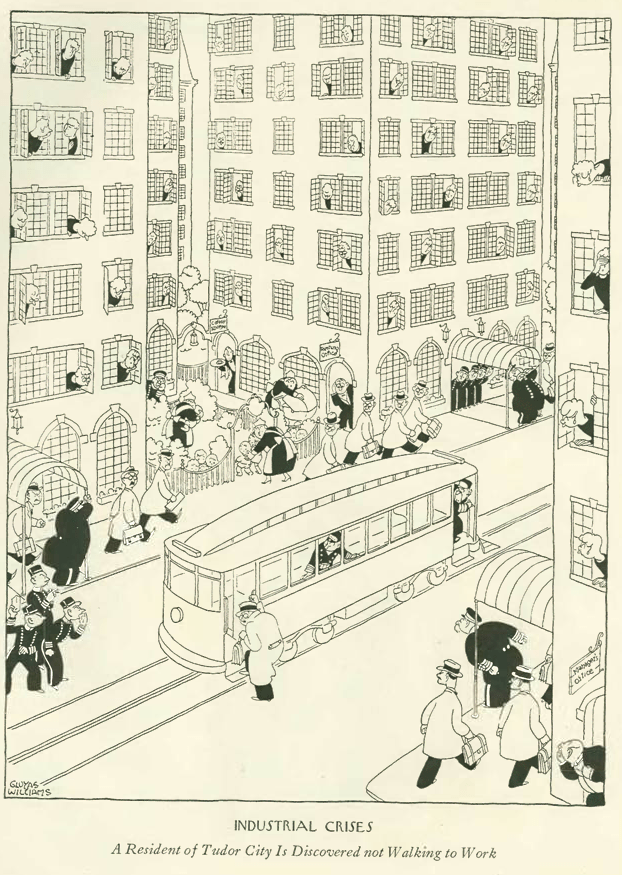

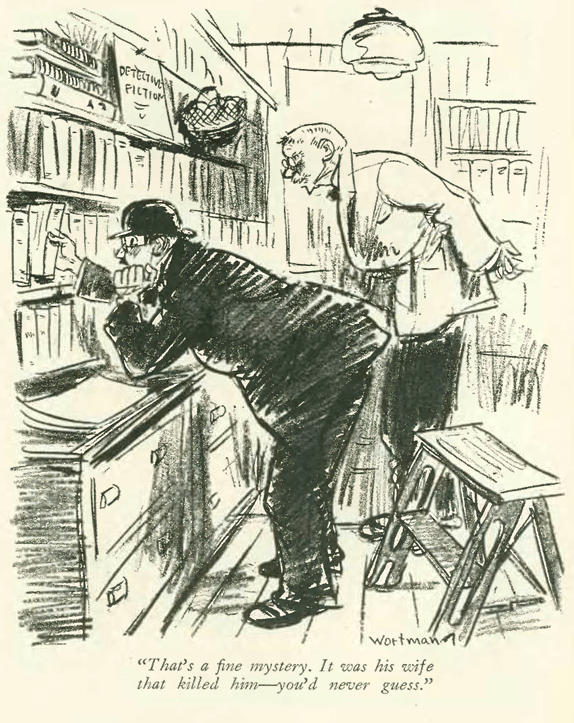

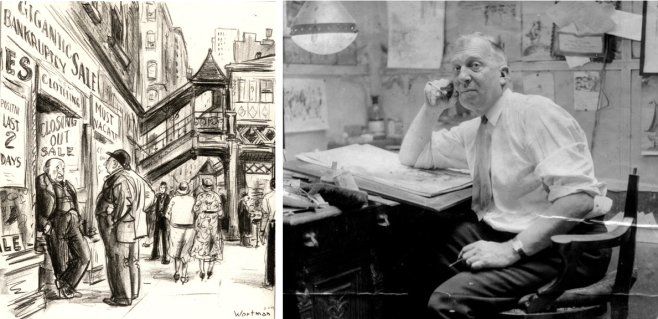

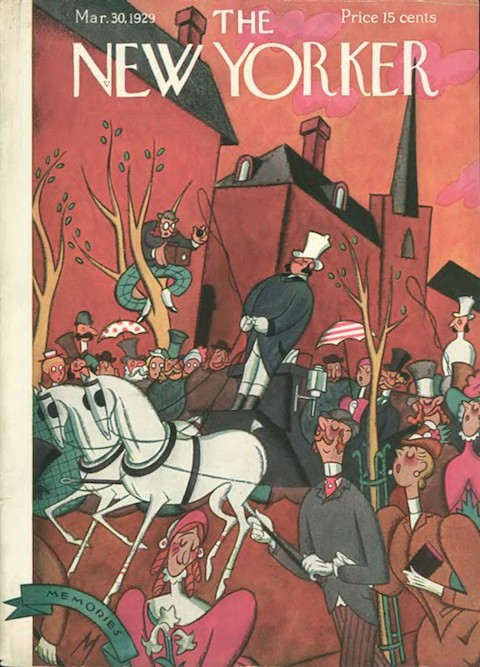

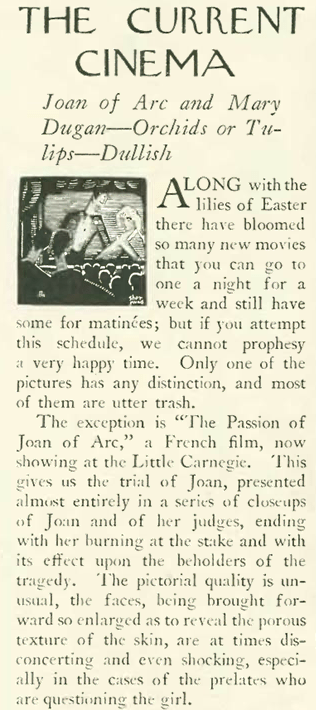

…our June 8 comics are from Helen Hokinson, who offered a full page of illustrations from a “Fifth Avenue Wedding”…

…while Leonard Dove peeked in on a wastrel son and his disappointed father…

…and we have an awkward moment revealed by Carl Kindl…

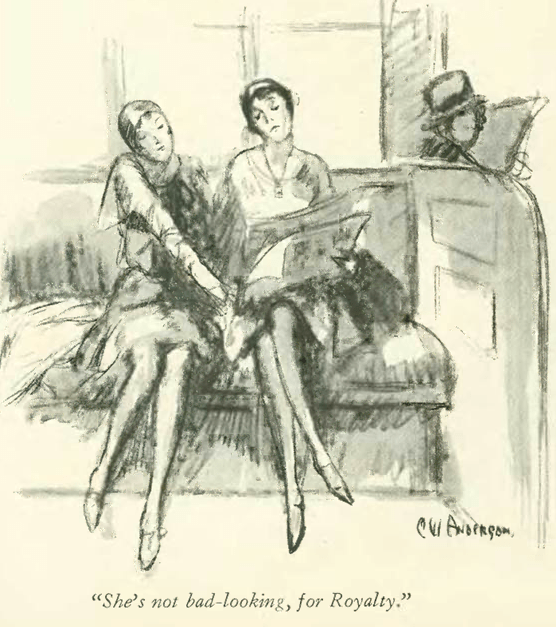

…and an observation by C.W. Anderson on the minimalism of modernist design…

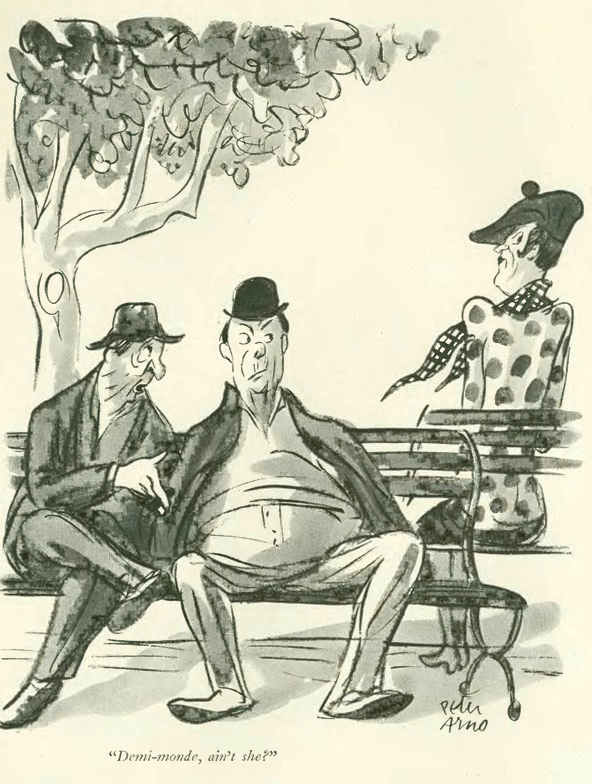

…and finally, Peter Arno’s take on the challenges of shooting sound motion pictures…

Next Time: Something Old, Something New…