Although its founding editor, Harold Ross, was raised in the rude surroundings of a Colorado mining town and often displayed the manners of a backwoodsman, the New Yorker nevertheless looked down its sophisticated nose at most anything west of the Hudson, and the middle west was reserved for particular ridicule in its homespun piety and small city boosterism.

Enter one Marion Talley, a child prodigy from the tiny town of Nevada, Missouri. After appearing in a lead role at age 15 for the Kansas City Grand Opera, excited civic leaders raised enough money to send Talley to New York to study voice. Four years later (February 1926) she made her Metropolitan Opera debut as Gilda in Rigoletto — at that time the youngest prima donna to appear on the Met stage. A delegation of Kansas City’s two hundred leading citizens (including the mayor) travelled to New York via special train to attend the performance. Adding to the spectacle, a noisy telegraph machine was set up backstage so Talley’s father could send dispatches back home during the performance. Writing in his “A Reporter at Large” column for the New Yorker’s Feb. 27, 1926 issue, Morris Markey scoffed at the hype and Babbitry on display:

The New Yorker (via E.B. White in “Notes & Comment”) caught up with Talley more than three years later in the April 20, 1929 issue, her short career seemingly over, her voice perhaps destined for nothing more than “hog-calling”…

When Talley’s Met contract was not renewed for the 1929 season, she announced her plans to retire to a wheat farm in Kansas (hence the hog calling reference). She did, however, try to revive her career on concert tours and then on her own NBC Radio program (1936-1938), sponsored by Ry-Krisp. She made one film, the 1936 musical Follow Your Heart, but after its tepid reception the 30-year-old Talley decided to retire from show business.

Talley married twice — to pianist Michael Rauchelsen (1932–1934) and to music critic Adolph Eckstein (1935–1942), the latter with whom she had a daughter, Susan. Talley died in 1983 in Beverly Hills, California.

* * *

Dark Clouds on the Horizon

The April 20, 1929 “Talk of the Town” made passing mention of a man who would be instrumental in the stock market crash later that year—National City Bank President Charles E. Mitchell:

The “Talk” item references a $25 million advance Mitchell offered to stock market traders who were getting the yips in an overheated market. This happened after a “mini crash” on March 25, 1929, when the Federal Reserve told its banks to withhold all loans to finance securities. Mitchell’s announcement apparently reassured the public enough to stop the panic, but in reality it only delayed the inevitable—a major market crash brought on in large part by the over-selling of securities by Mitchell’s bank.

The “Talk” item continued with this observation on the Panic of 1907, and how banker J.P. Morgan had also offered $25 million to bring the market back to earth:

* * *

Funny Girl

One of Broadway’s biggest stars in the 1920s, Fanny Brice (1891-1951) was profiled by Niven Busch Jr. in the April 20 issue. In addition to her work with the Ziegfeld Follies and other stage productions, by 1929 the comedian, singer and actress had recorded two-dozen songs and appeared in the 1928 film, My Man. Brice’s star would continue to rise in the 1930s and 40s, especially on the radio portraying the bratty toddler “Baby Snooks.” Here are the opening lines of the profile, which included a caricature of Brice by Miguel Covarrubias:

* * *

From its very beginnings comic verse played an important role in the pages of the New Yorker. The subjects of my previous blog post (Generation of Vipers), sisters Elinor Wylie and Nancy Hoyt, both contributed comic poems to the magazine, as did Clarence Knapp, a former mayor of Saratoga, New York, who also wrote prose pieces on that city’s famed horse racing scene. According to Judith Yaross Lee (Defining New Yorker Humor, p. 354), Knapp was a New Yorker insider who penned a total of 14 mock-melodramatic “sob ballads” between 1927 and 1930. Lee observes that Knapp’s ballads followed a fixed formula, two 16-line stanzas followed by eight-line refrains, that “joked about present social values by invoking past forms.”

* * *

They Loved a Parade

After the passing of literary giant Victor Hugo in 1885 (his funeral attracted two million mourners), Paris became known for its spectacular funeral processions. So when famed French general and (WWI) Supreme Allied Commander Marshal Ferdinand Foch died on March 20, 1929, the City of Light turned out in droves to say goodbye. On hand to report the scene was the New Yorker’s Paris correspondent, Janet Flanner, aka Genêt:

By Flanner’s account, Foch’s send-off easily matched Hugo’s in terms of crowd size:

* * *

The Art of Smoking

Cigarette manufacturers used a variety of marketing techniques to promote their tobacco products. During the late 1920s and early 30s R.J. Reynolds sought to attract more women smokers through a series of stylish ads for its Camel brand that evoked a softly elegant world. These ads were illustrated by Carl Erickson (1891–1958), a fashion artist whose work was widely seen in Vogue and in promotions for Coty cosmetics. This ad appeared in the April 20 issue of the New Yorker:

While studying at Chicago’s Academy of Fine Arts, Erickson was nicknamed “Eric,” a name he later used to sign his works. Also a successful portrait artist, Erickson lived part of his professional life in France (1920 to 1940) with his wife, the fashion illustrator Lee Creelman. Below are several examples of Erickson’s Camel work, including two back page illustrations from Delineator, a women’s fashion magazine that featured Butterick sewing patterns.

And From Our Other Advertisers…

With our Cuba relations once again eroding, let’s look back 89 years to a time when affordable, care-free living could be yours in sunny Havana…

…or in the days before foam rubber, “ozonized” animal hair gave bounce to your rugs…

…or the modestly well-off could contemplate an apartment on Park Avenue…

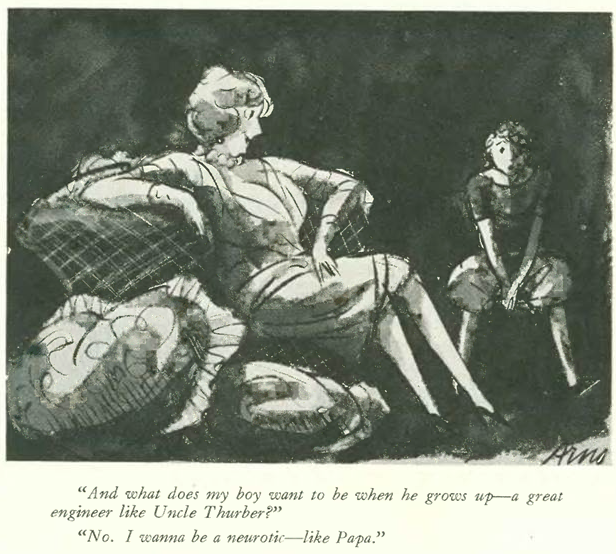

Our cartoons come courtesy of Garrett Price (1895-1979), who would contribute hundreds of cartoons as well as 100 covers during his more than 50 years with the New Yorker. An excellent look at Price’s life and work can be found in The Comics Journal…

…Denys Wortman (1887-1958) looked in on a bookseller with a “spoiler” problem. From 1924 to 1954 Wortman drew the nationally syndicated comic strip Metropolitan Movies for the New York World. The beautifully drawn strip offered a naturalistic portrayal of daily life in New York City…

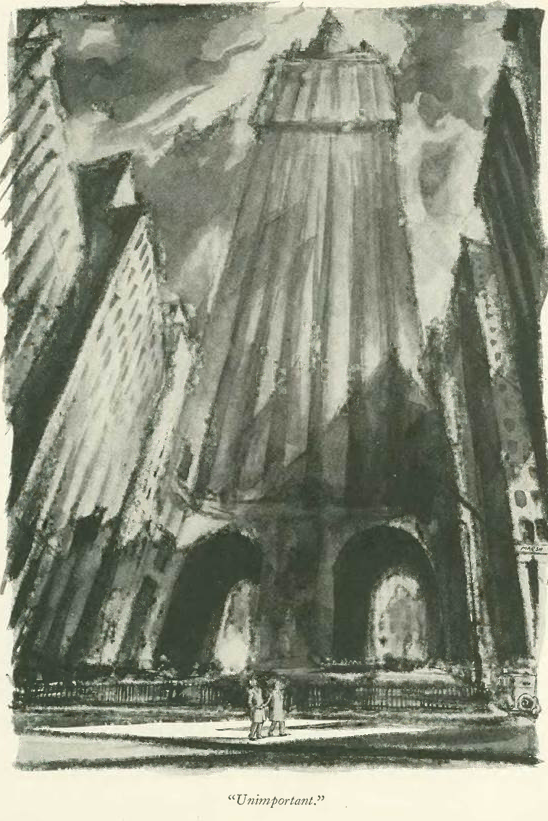

…and John Reynolds looked in on the challenges of the architecture profession. Reynolds contributed 34 drawings to the New Yorker from 1928 to 1930.

Next Time: Hello Molly…