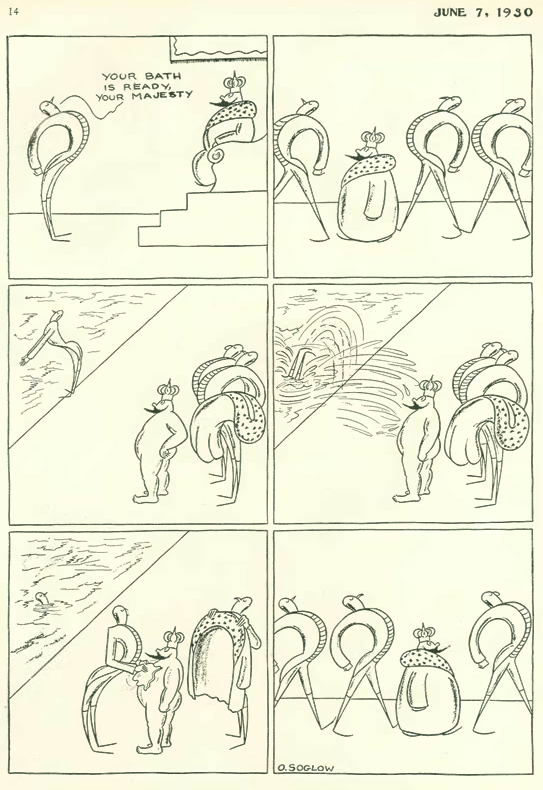

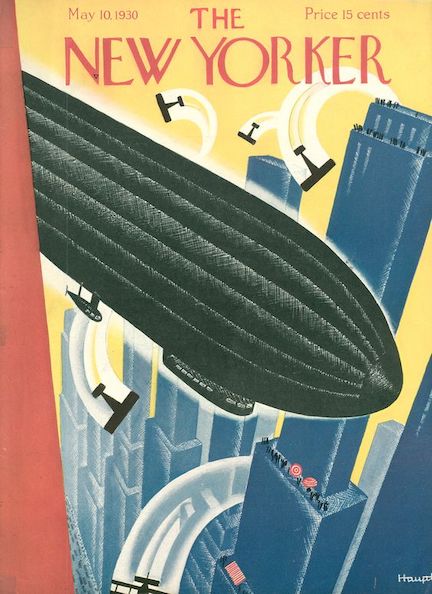

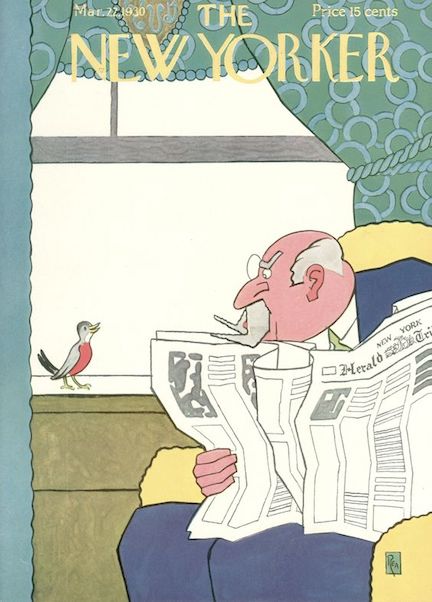

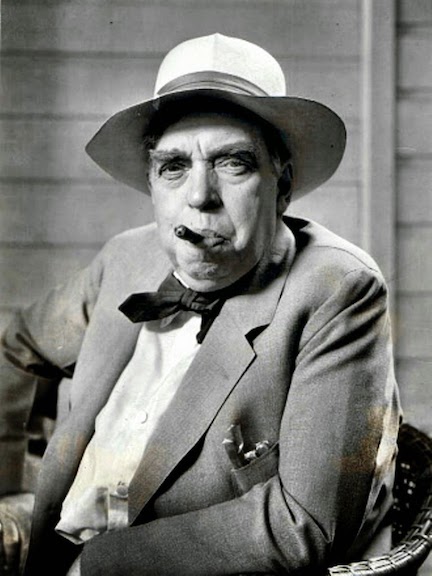

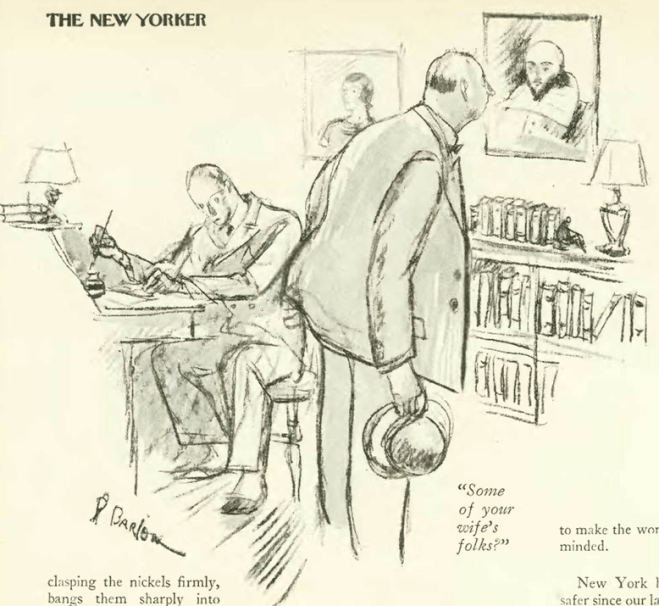

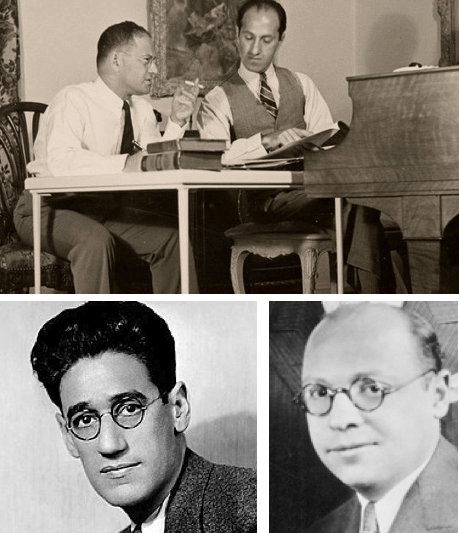

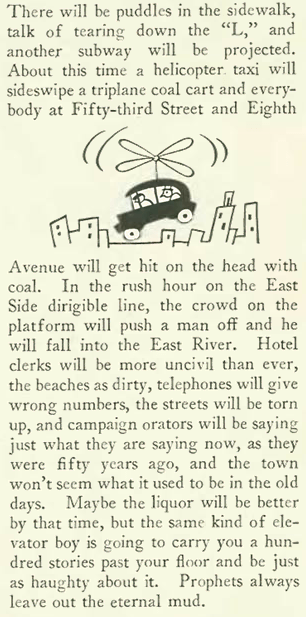

Like his New Yorker colleague Reginald Marsh, Otto Soglow trained in the “Ashcan School” of American art, and his early illustrations favored its gritty urban realism. He had his own life experience to draw upon, being born to modest means in the Yorkville district of Manhattan.

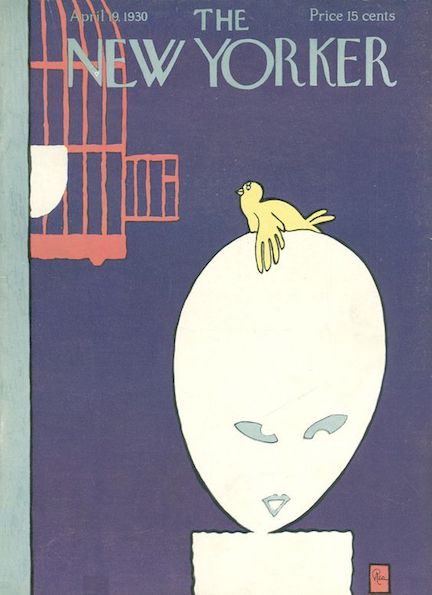

But Soglow (1900-1975) would soon abandon the gritty style in the work he contributed to the New Yorker…

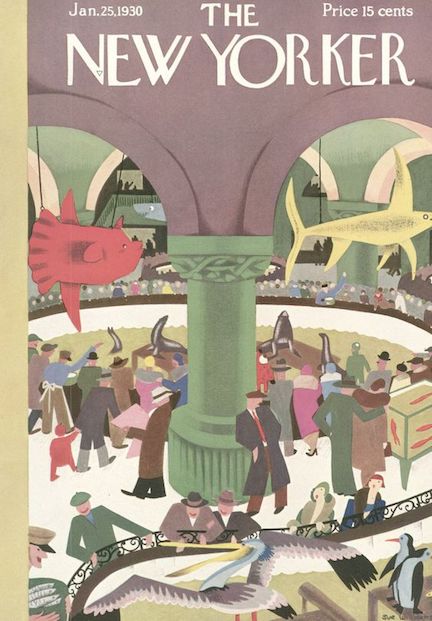

…and in the June 7, 1930 issue, Soglow would publish his first Little King strip, which would launch the 29-year-old into fame and fortune…

Did Soglow know he was on to something big with that first Little King cartoon? Well Harold Ross (New Yorker founding editor) liked what he saw, and asked Soglow to produce more. After building up an inventory over nearly ten months, Ross finally published a second Little King strip on March 14, 1931. It soon became a hit, catching the attention of William Randolph Hearst, who wanted the strip for his King Features Syndicate.

After Soglow fulfilled his contractural obligation to The New Yorker, The Little King made its move to King Features on Sept. 9, 1934, and the strip ran until Soglow’s death in 1975. After his move to King Features, Soglow continued to contribute cartoons to The New Yorker, but with other themes.

You can read more about Soglow and The Little King in The Comics Journal.

* * *

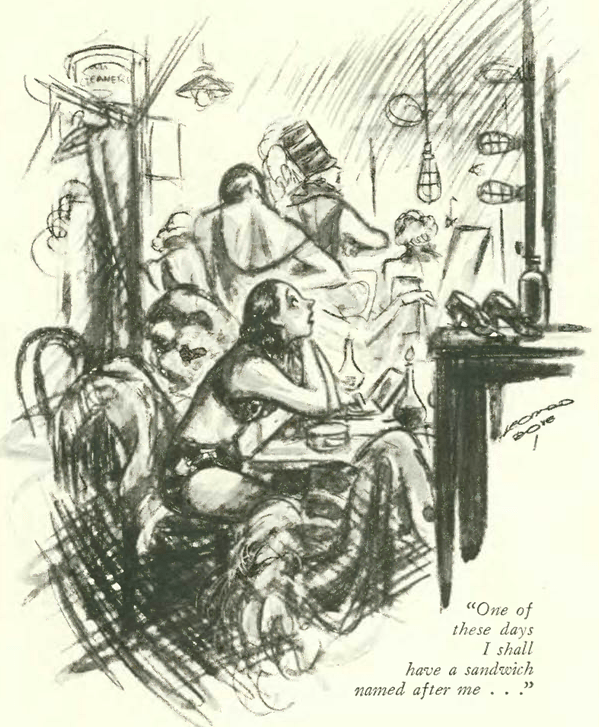

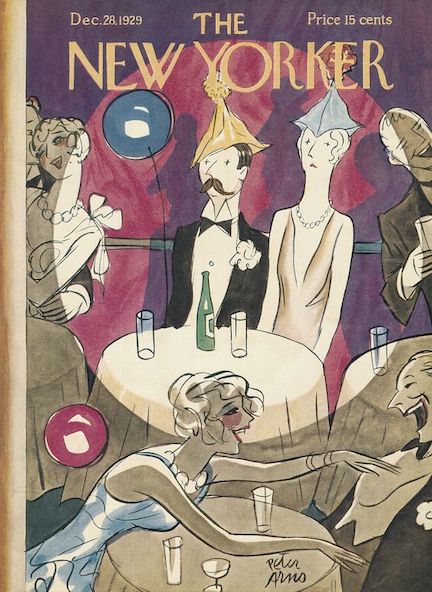

The Party’s Definitely Over

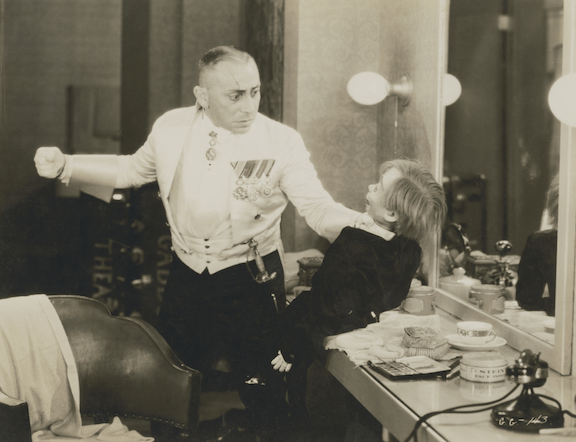

During the summer of 1925, a young writer at Vanity Fair named Lois Long would take over The New Yorker’s nightlife column, “When Nights Are Bold,” rename it “Tables For Two,” and set about giving a voice to the fledgling magazine as well as chronicling the city’s Jazz Age nightlife. There were accounts of Broadway actors mingling with flappers and millionaires at nightclubs and speakeasies, but Long also spoke out on issues such as Prohibition, taking the city’s leaders to task for raids on speakeasies and other heavy-handed tactics contrary to the spirit of the times. “Tables For Two” would go on hiatus with the June 7, 1930 issue, and appropriately so, as the deepening Depression gave the the city a decidedly different vibe. In her “final” column Long would write about the Club Abbey, a gay speakeasy operated by mobster Dutch Schultz…

…and she would update her readers on “Queen of the Night Clubs” Texas Guinan, whose Club Intime was sold to Dutch Schultz and replaced by his Club Abbey…

Long’s column would signal a definitive end to whatever remained of the Roaring Twenties. It would also signal the end to some of those associated with those heady times. Texas Guinan’s Lynbrook plans would flop, and Gene Malin’s Club Abbey would close in less than a year. Both would both be dead by 1933—Malin would die in a car accident in 1933, and amoebic dysentery would claim Guinan that same year. Dutch Schultz would be gunned down by gangsters in 1935.

Lois Long, however, would continue to write for The New Yorker for another forty years, and would prove to be as innovative in her fashion column, “On and Off the Avenue,” as she was as a nightlife correspondent.

* * *

Gone to the Dogs

In another installment of his pet advice column (June 7), James Thurber gave us one of his classic dogs…a disinterested bloodhound…

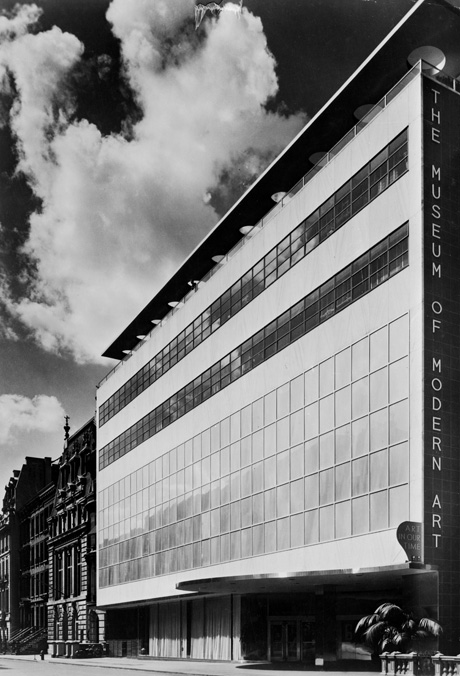

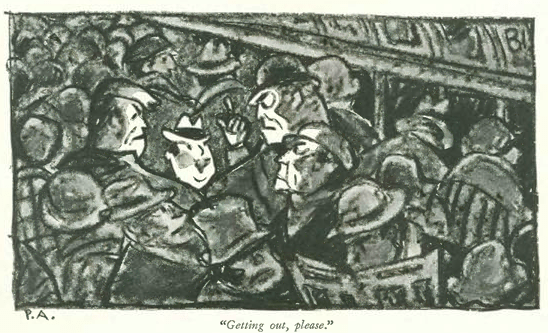

…while Thurber’s buddy and office mate E.B. White commented (in the March 31 issue) on a recent poll conducted among students at Princeton, discovering among other things that New Yorker cartoonist Peter Arno was preferred over the old masters…

* * *

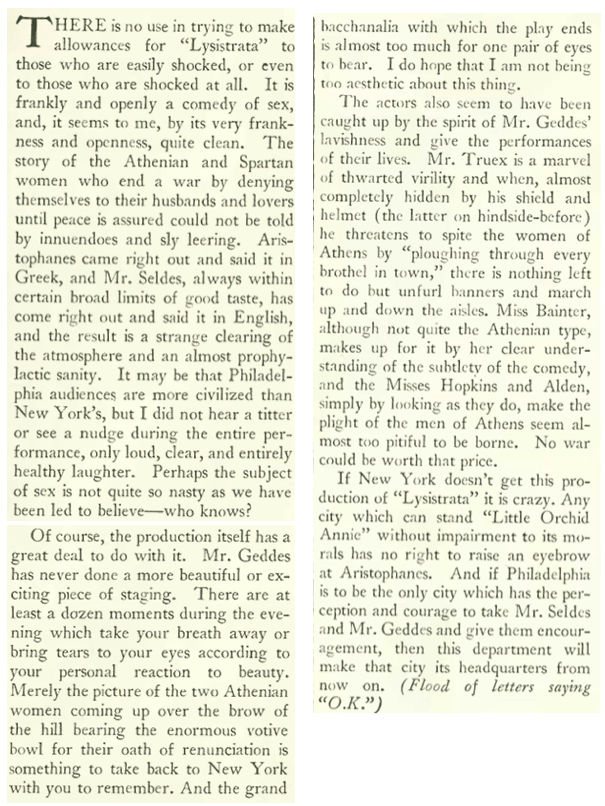

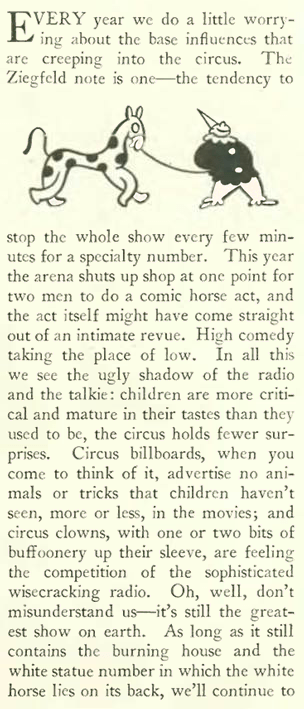

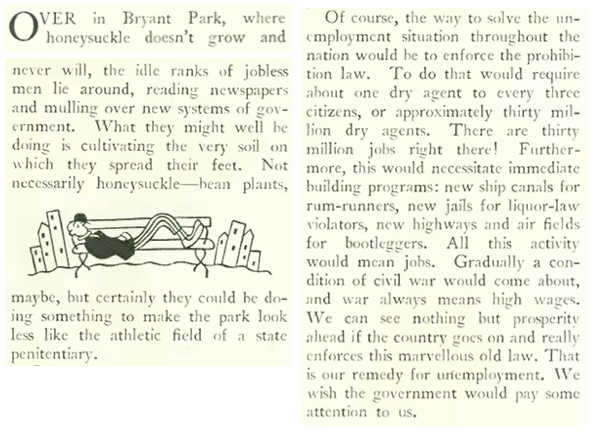

We Like It Fine, Thank You

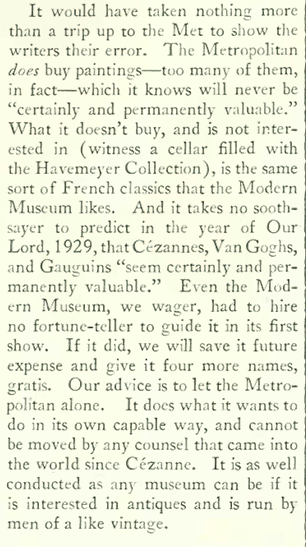

The New Yorker dedicated a full page of the March 31 issue to a tongue-in-cheek rebuttal directed at the New York Evening Journal, which had reprinted one of Peter Arno’s cartoons to illustrate the moral cost of Prohibition. I believe the author of the rebuttal is E.B. White (note how he refers to Arno as “Mr. Aloe”).

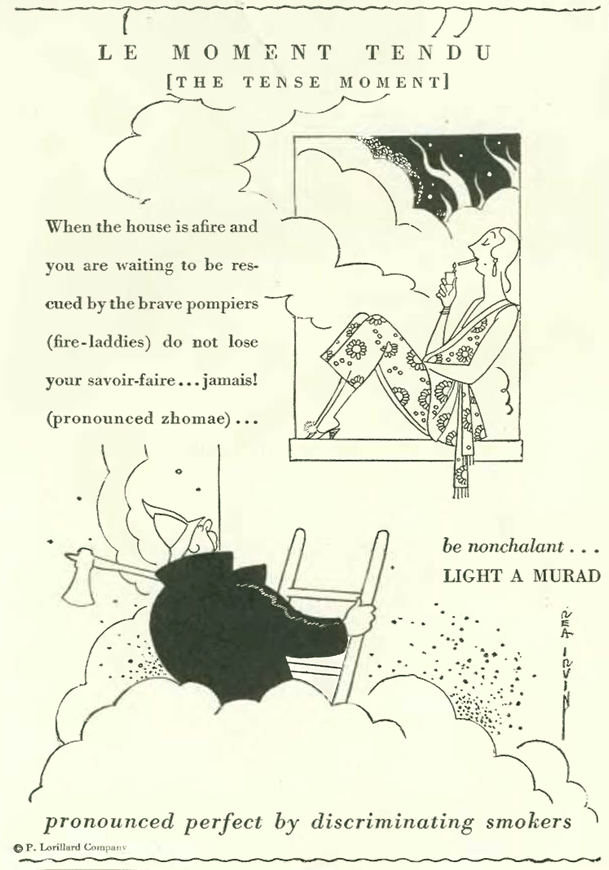

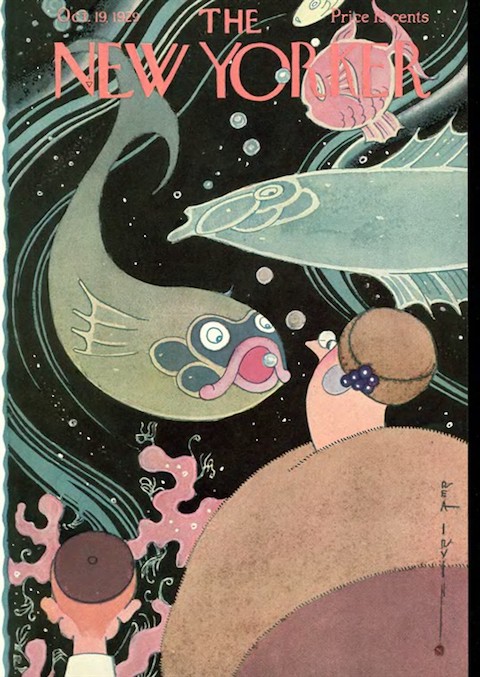

…also in the May 31 issue, Rea Irvin changed things up, at least temporarily, with some new artwork for the “Goings On About Town” section. The entries themselves were often clever, such as this listing for a radio broadcast: PRESIDENT HOOVER—Gettysburg speech. Similar to Lincoln’s but less timely…

* * *

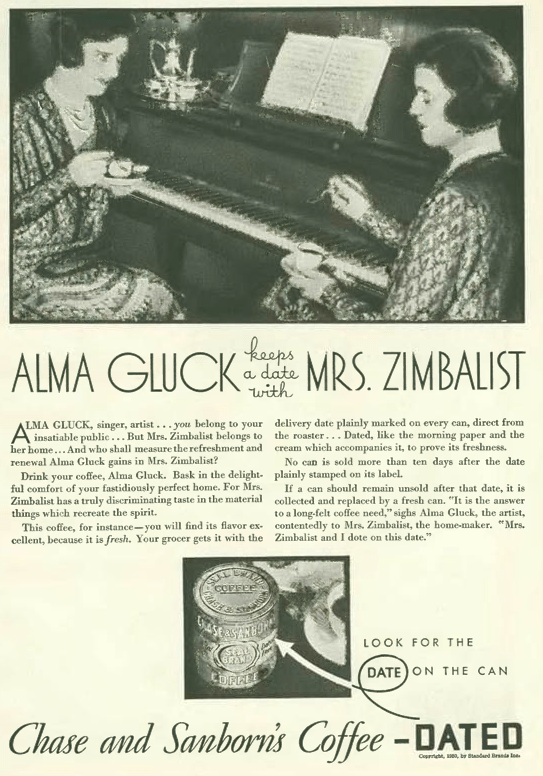

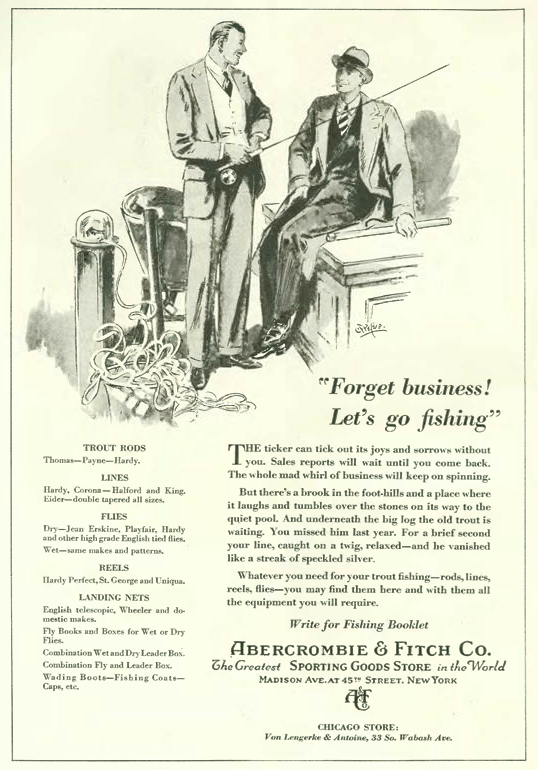

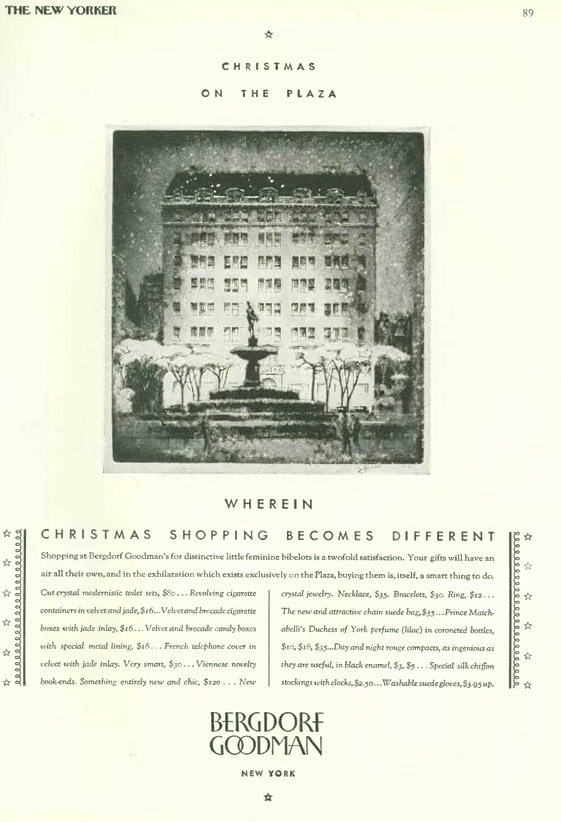

From Our Advertisers

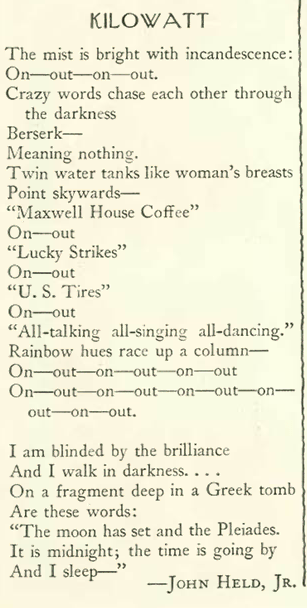

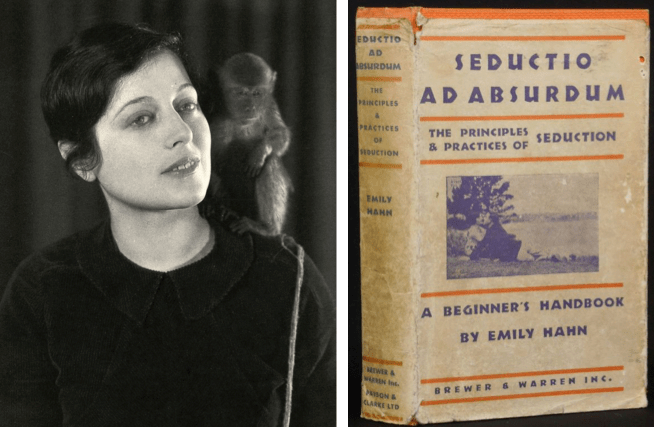

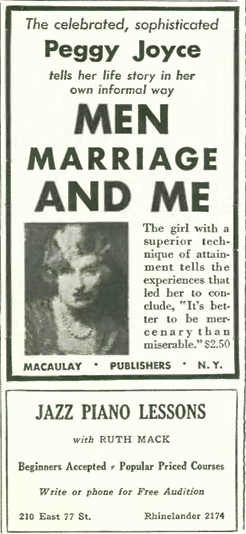

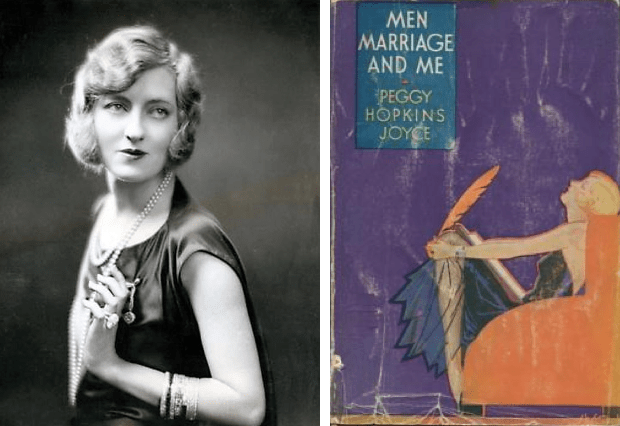

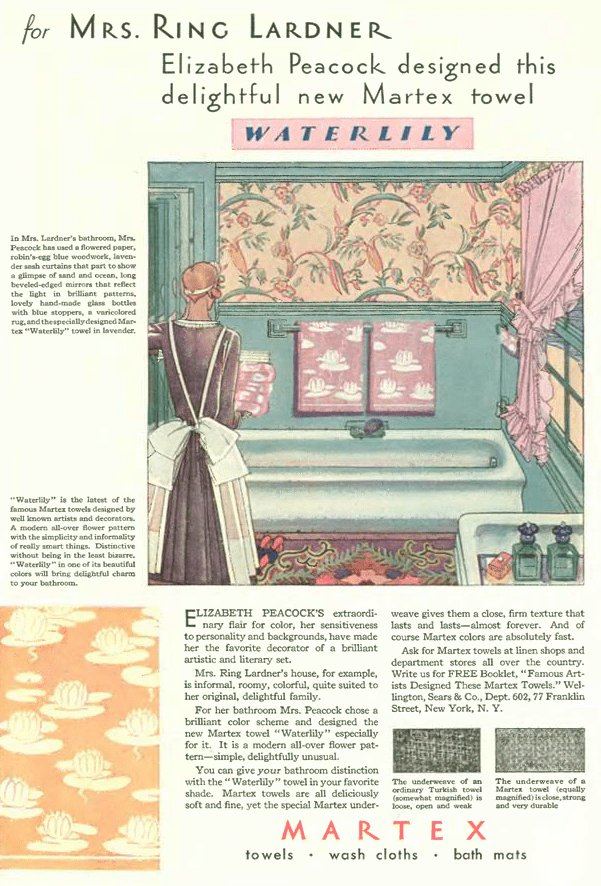

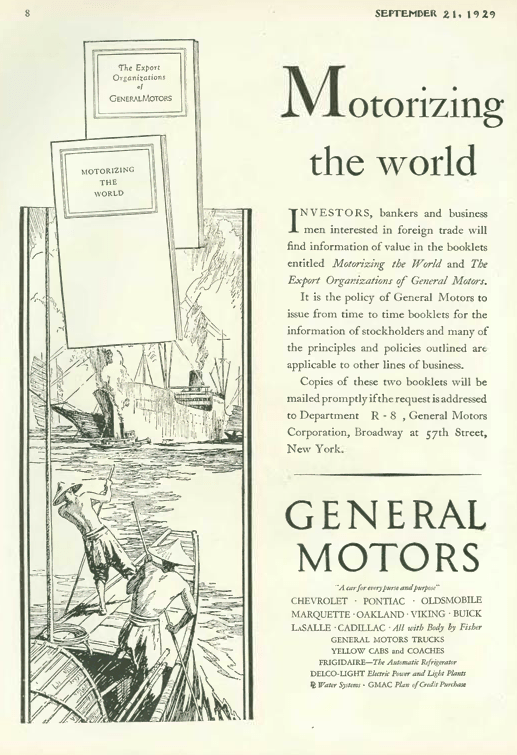

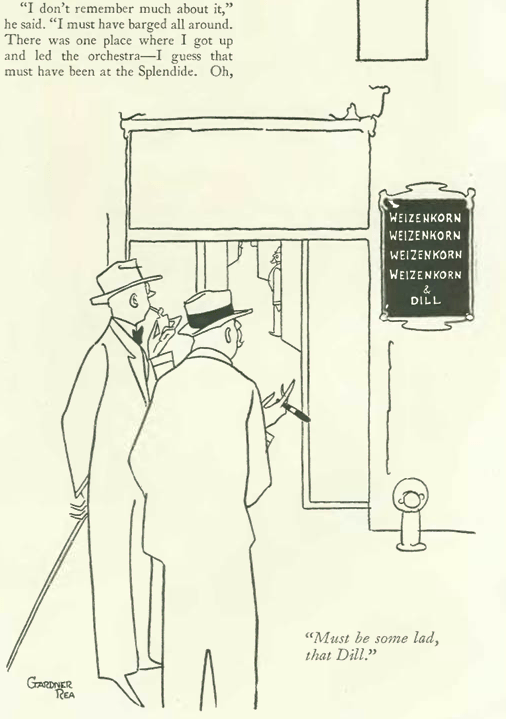

New Yorker cartoonists can be found throughout the advertisements — from left, Julian De Miskey, Rea Irvin and John Held, Jr…

…and in the June 7 issue we find an unusual ad for a used car…a sign of the times, no doubt…

…before it was associated with Germany’s Nazi Party (especially after it seized power in 1933), for thousands of years the swastika had been widely used as a religious or good luck symbol…

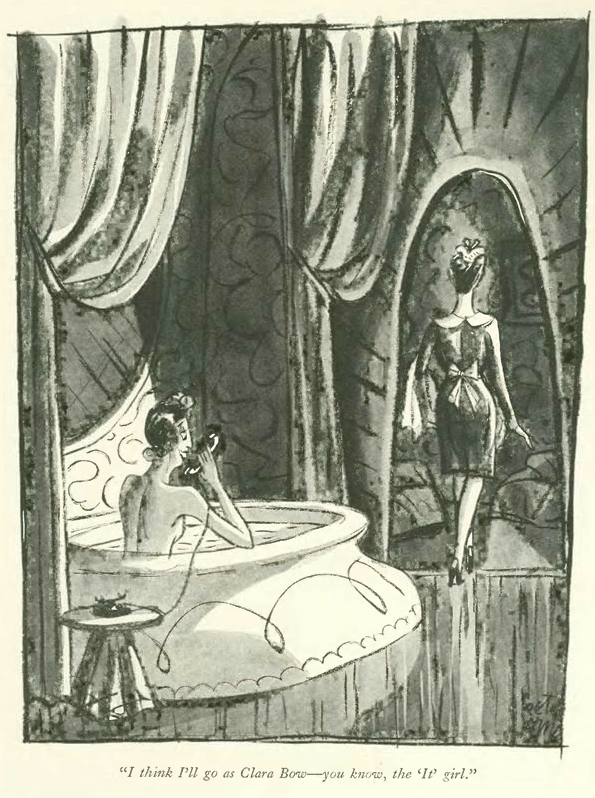

…Actress Clara Bow was famously pictured sporting a “good luck” swastika as a fashion statement in this press photo from June 1928, unaware that in a few years the symbol would become universally associated with hate, death and war…

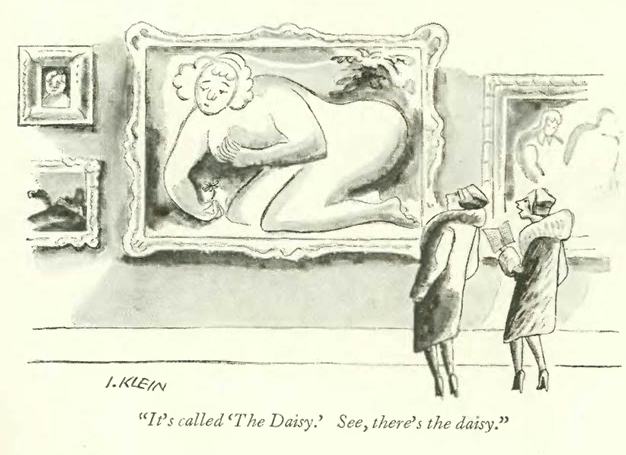

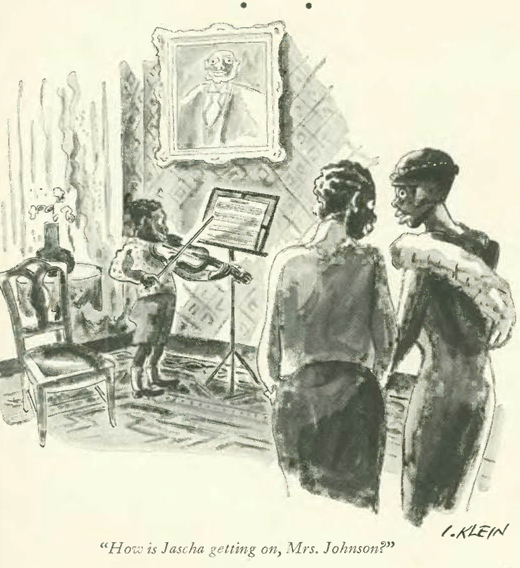

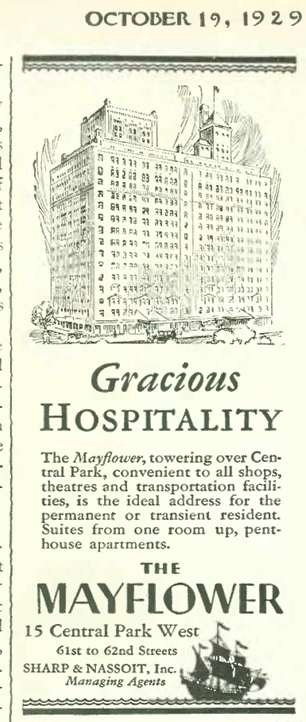

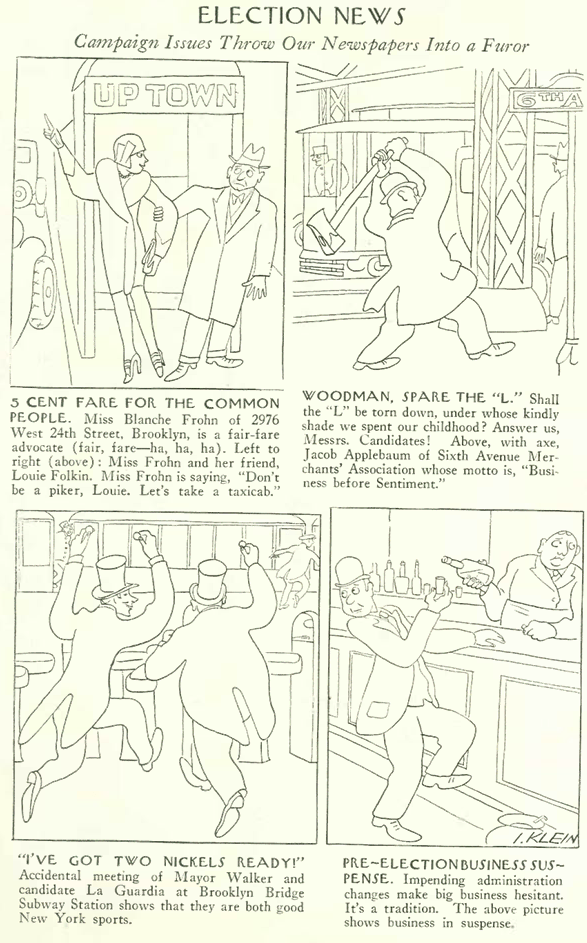

…on to our cartoons, Isadore Klein illustrated a cultural exchange…

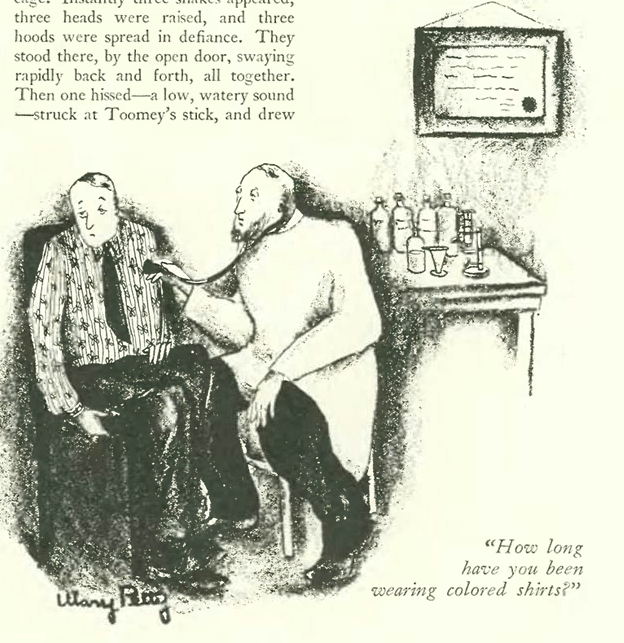

…Garrett Price gauged the pain of a plutocrat…

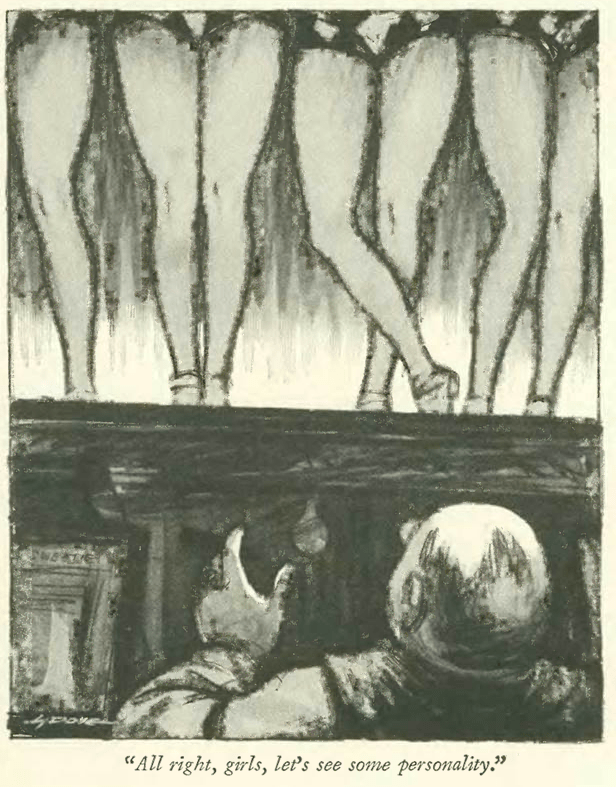

…Alan Dunn eavesdropped on some just desserts…

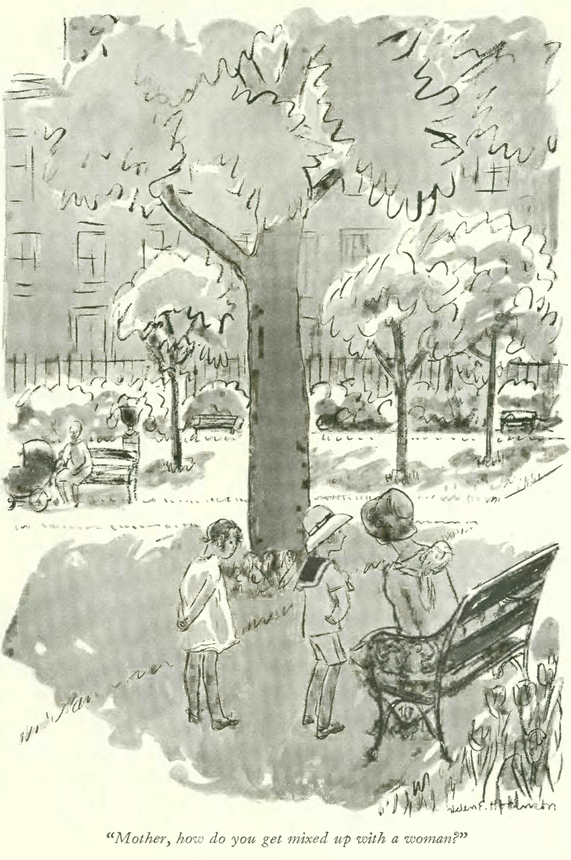

…Helen Hokinson found humor in the mouths of babes…

…as did Alice Harvey…

…Leonard Dove examined one woman’s dilemma at a passport office…

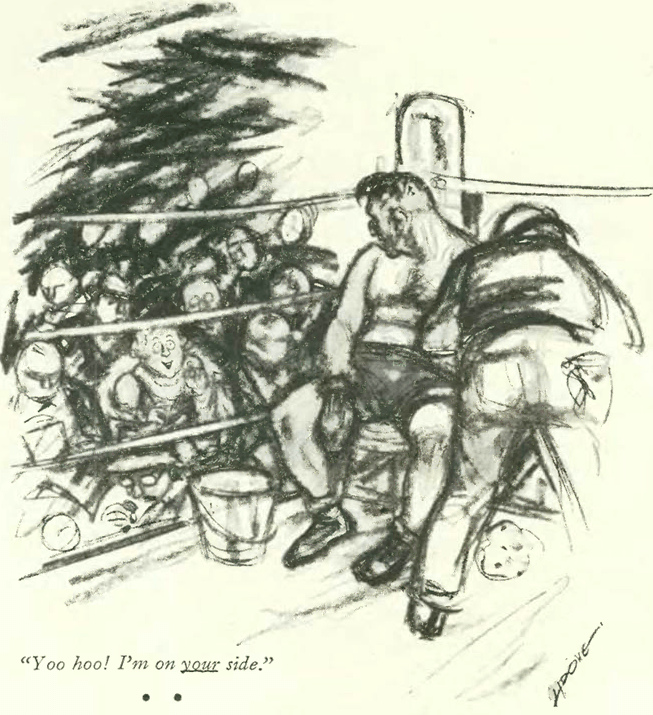

…and Peter Arno, who found some cattiness at ringside…

Next Time: Germany’s Anti-Decor…