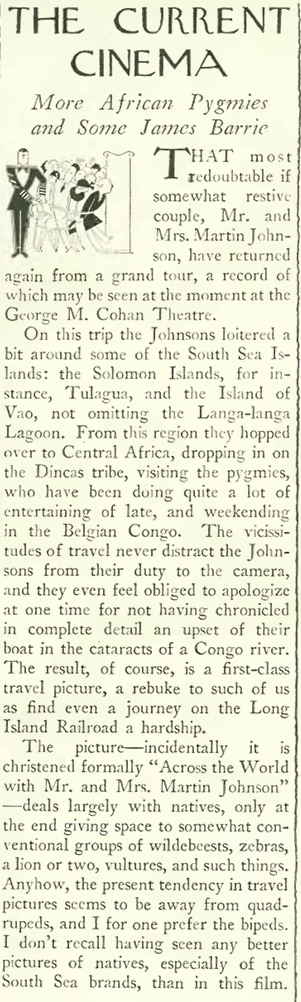

Still considered one of the greatest anti-war films ever made, All Quiet on the Western Front opened in New York on April 29, 1930 to strong reviews. Based on Erich Maria Remarque’s novel of the same name, the film’s depictions of the horrors of war were so realistic and harrowing that it was banned in a number of countries outside of the U.S.

Banned, that is, by nations gearing up for war. In Germany, Nazi brownshirts disrupted viewings during its brief run in that country, tossing smoke bombs into cinemas among other acts of mayhem. Back in the U.S., The New Yorker’s John Mosher attended a screening at a “packed” Central Theatre:

Mosher found the film’s adaption from the novel wanting in places, but overall praised the acting and the quality of the picture…

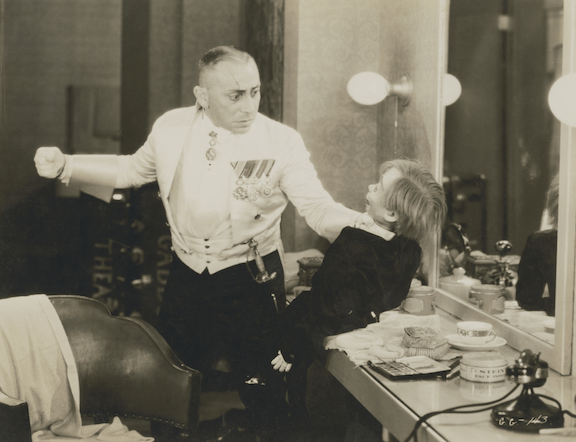

…and just in case some audiences were put off by the blood and guts, Universal promoted other themes on its lobby cards…

…and just in case some audiences were put off by the blood and guts, Universal promoted other themes on its lobby cards…

* * *

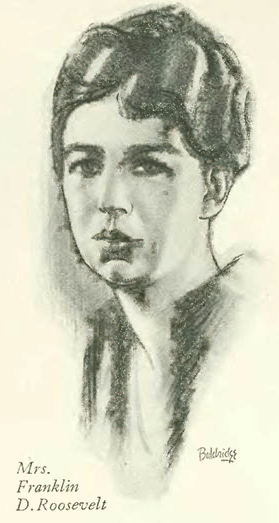

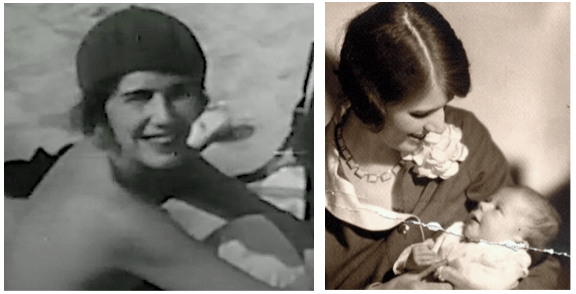

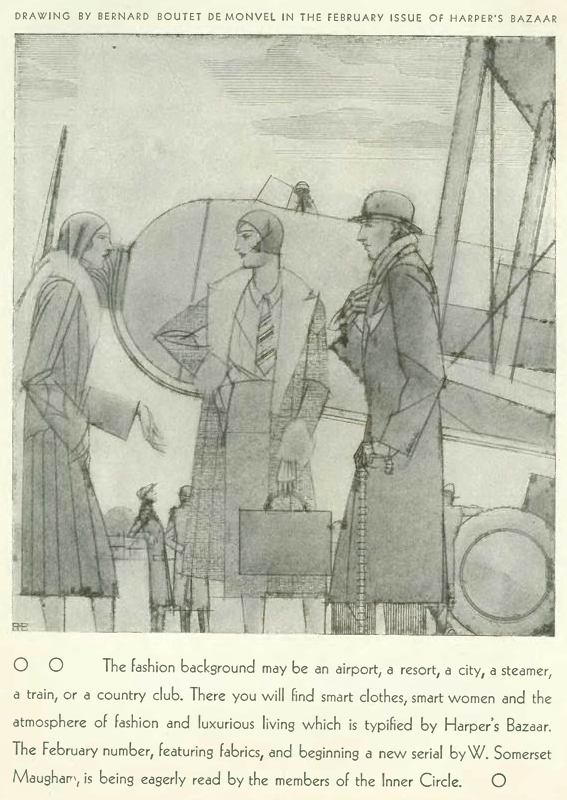

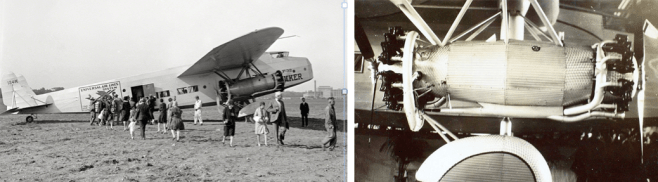

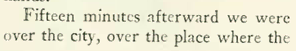

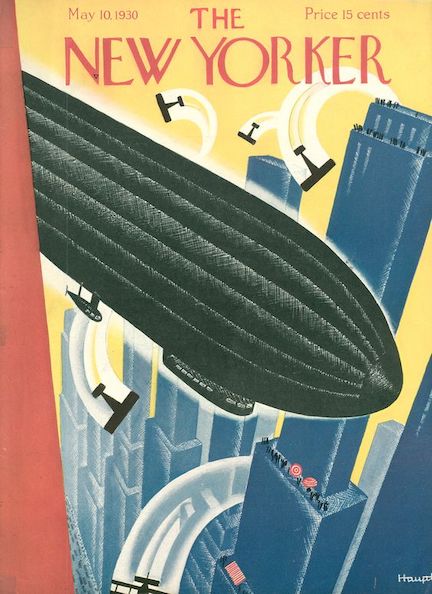

More Than a Stunt

In her profile of aviator Elinor Smith (1911-2010), writer Helena Huntington Smith took great pains to distinguish Elinor from other “lady fliers” who were little more than passengers in various flying exploits. Like Amelia Earhart, Smith had the bona fides of a true aviator: in 1927 she become the youngest licensed pilot in the world at age 16, learning stunt flying at an early age. When she was 17 she smashed the women’s flying endurance record by soloing 26½ hours, and in the following month set a woman’s world speed record of 190.8 miles per hour. In March 1930 she set a women’s world altitude record of 27,419 feet (8,357 m), breaking that record in 1931 with a flight reaching 32,576 feet. Smith would continue to fly well into old age. In 2000 she flew NASA’s Space Shuttle vertical motion simulator and became the oldest pilot to succeed in a simulated shuttle landing. In 2001 (at age 89) she would pilot an experimental flight at Langley AFB. An excerpt from the profile:

* * *

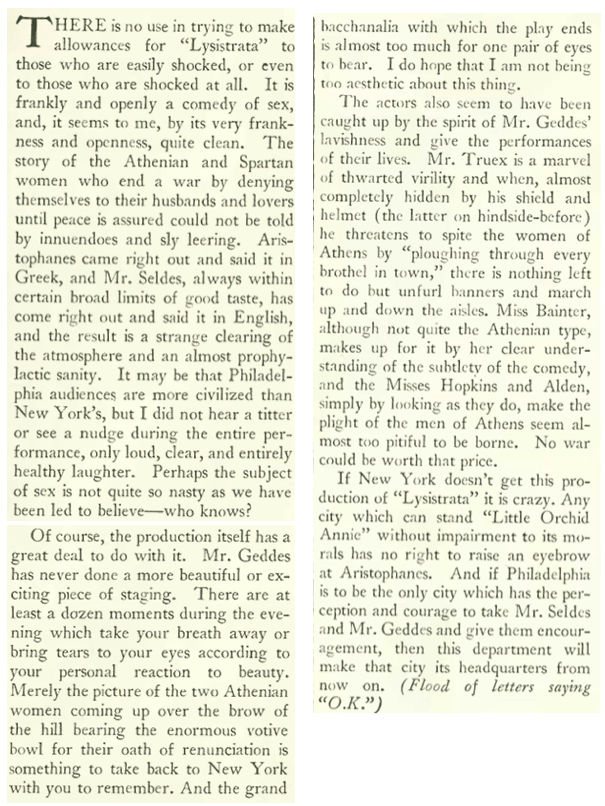

I’d Rather Be in Philadelphia

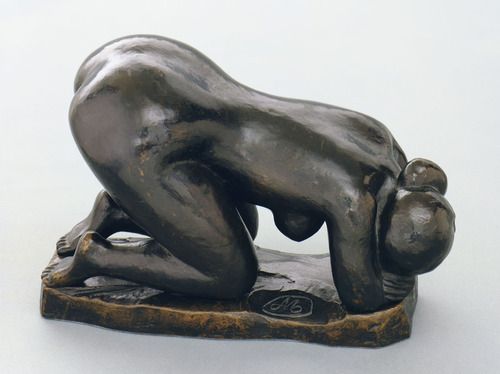

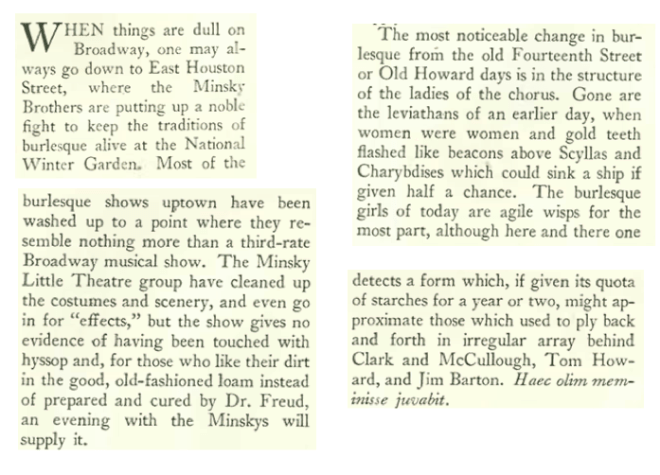

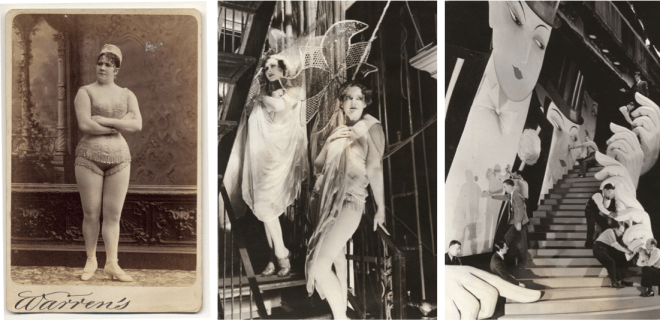

Theatre critic Robert Benchley was over the moon regarding a performance of Lysistrata staged by the Philadelphia Theatre Association. Benchley suggested the Philadelphians had “put New York to shame” in staging such a “festival of beauty and bawdiness…never seen on an American stage before.”

Benchley praised the seemingly advanced tastes of Philadelphia audiences as he continued to the lament the fact that the City of Brotherly Love had beaten New York to the punch with the staging of the play. He needn’t have worried much longer; the play would open on Broadway on June 5, 1930, at the 44th Street Theatre.

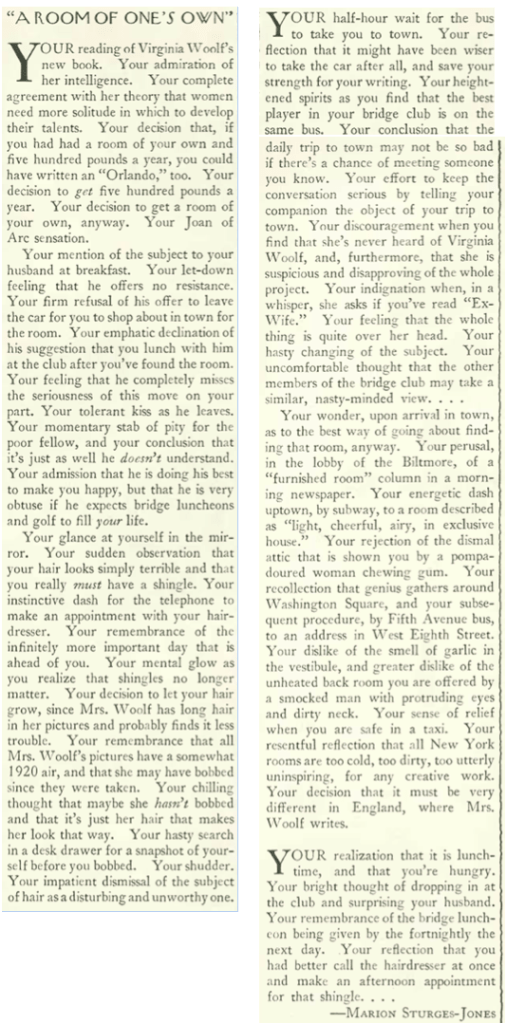

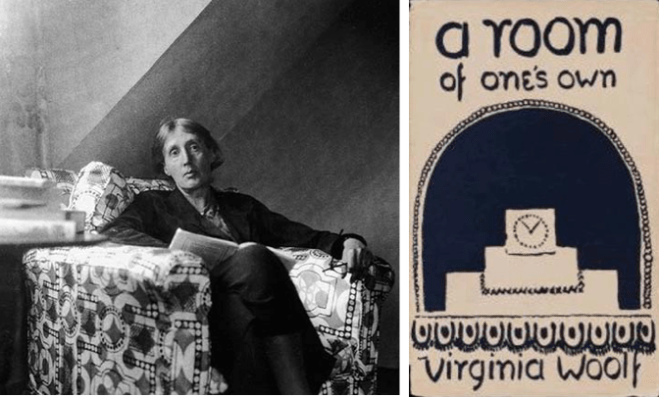

While we are on the subject of theater, Constantin Alajálov provided this lovely illustration of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya for The New Yorker’s theater review section…

* * *

Make ‘Em Dance, Boys

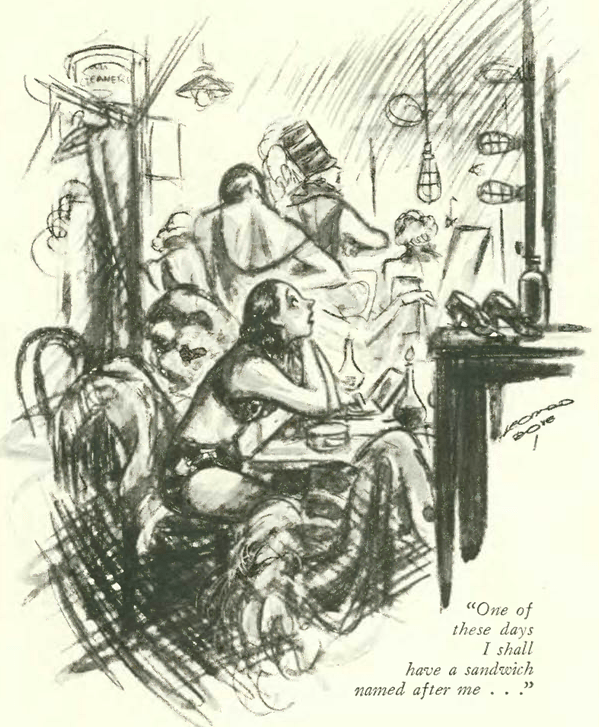

The author Robert Wilder contributed this interesting casual about the appearance of gangster Al Capone at a Chicago nightclub. Excerpts:

* * *

You Say You Want a Revolution?

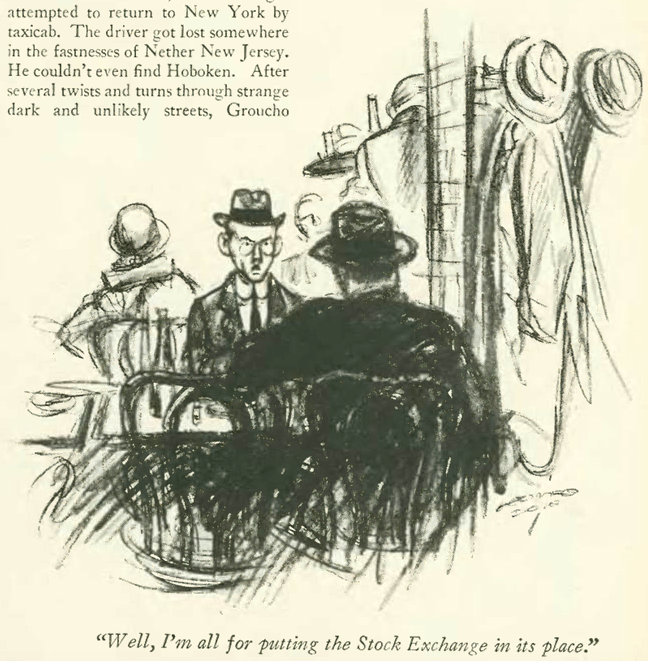

Alva Johnston offered his thoughts on how America could stage its own “Red Revolution,” given that Russia and several European countries had already experienced communist uprisings of their own, and also given that New York Police Commissioner Grover Whalen, always in search of problems that didn’t exist, had announced a new “Red Scare” in his fight against communism.

Tongue firmly in cheek, Johnston suggested how American know-how could be brought to bear in inciting a Red Terror. An excerpt:

* * *

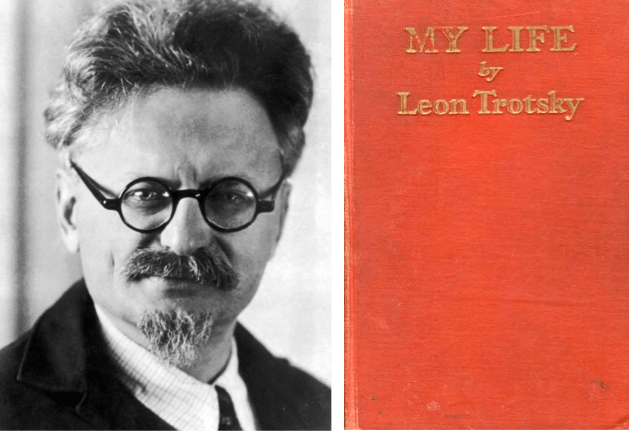

Speaking of Revolutionaries

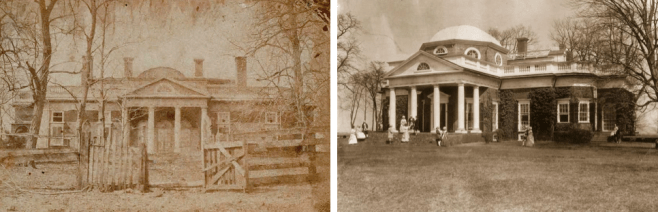

Thomas Jefferson’s home at Monticello is one of America’s most-visited historical sites, but in 1930 it was still something of a regional curiosity, having only been acquired in 1923 for the purposes of turning it into a public museum. Although Jefferson is well known today for his various inventions at Monticello, E.B. White was just learning about this side of the president in his weekly “Notes and Comment” dispatch:

* * *

Play Ball?

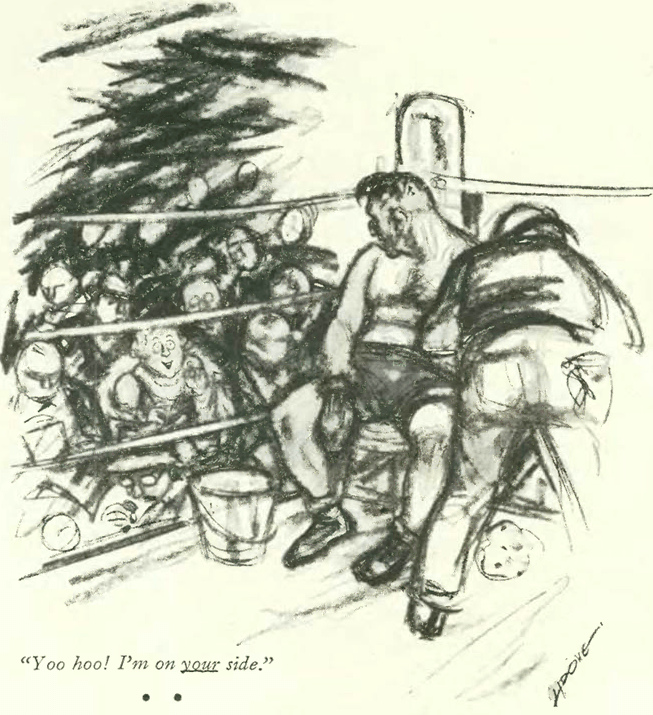

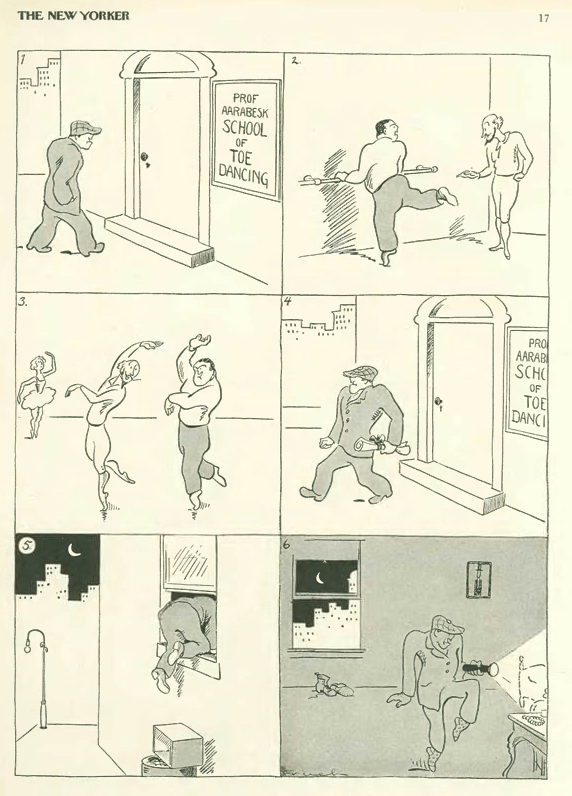

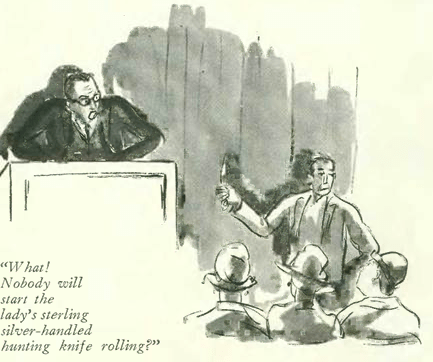

We are well into the spring of 1930, yet The New Yorker stood firm in its complete lack of baseball coverage. As I’ve noted before, the magazine covered virtually every sport from horse racing to rowing to badminton, and even lowered itself to regular features on college football and professional hockey, but not a line on baseball, save for an occasional note about the antics of Babe Ruth or the homespun goodness of Lou Gehrig. There were signs, however, that baseball was being played in a city blessed with three major league teams; we do find game times in the “Goings On About Town” section, as well as occasional baseball-themed filler art, and a comic panel in the May 10 issue by Leonard Dove:

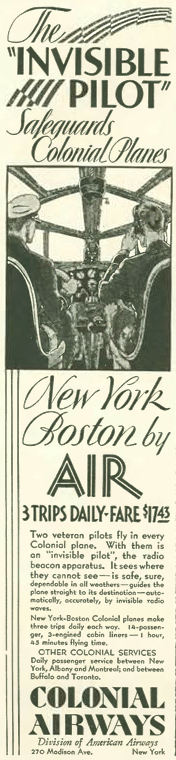

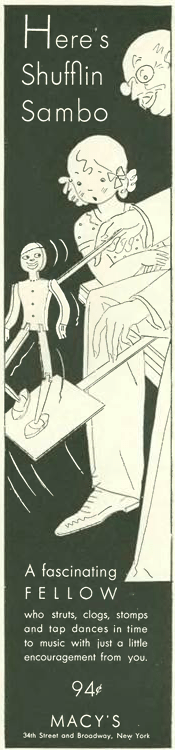

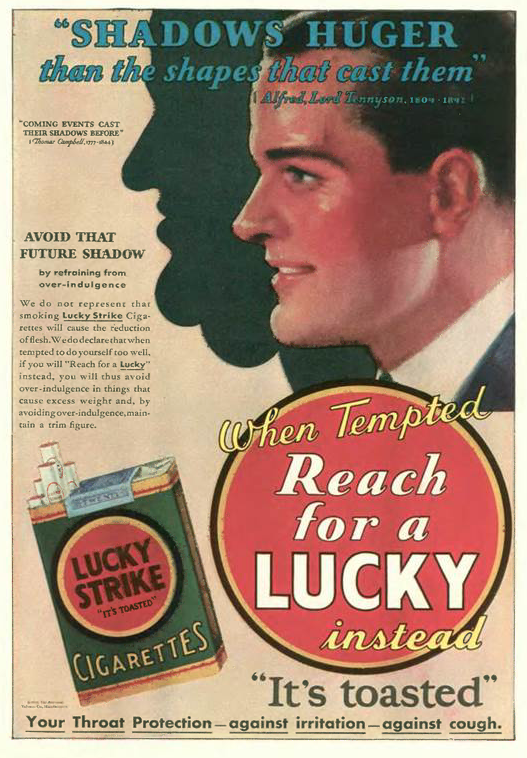

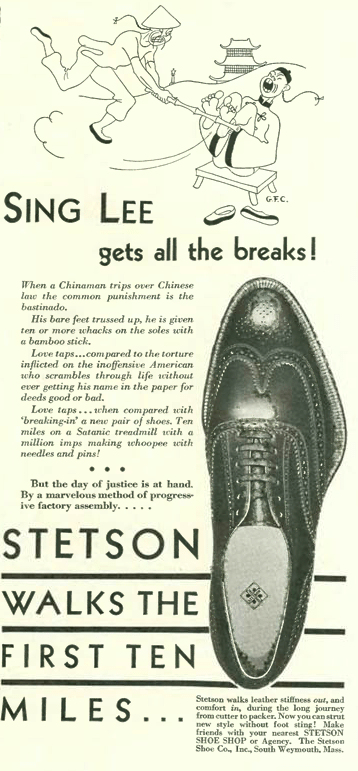

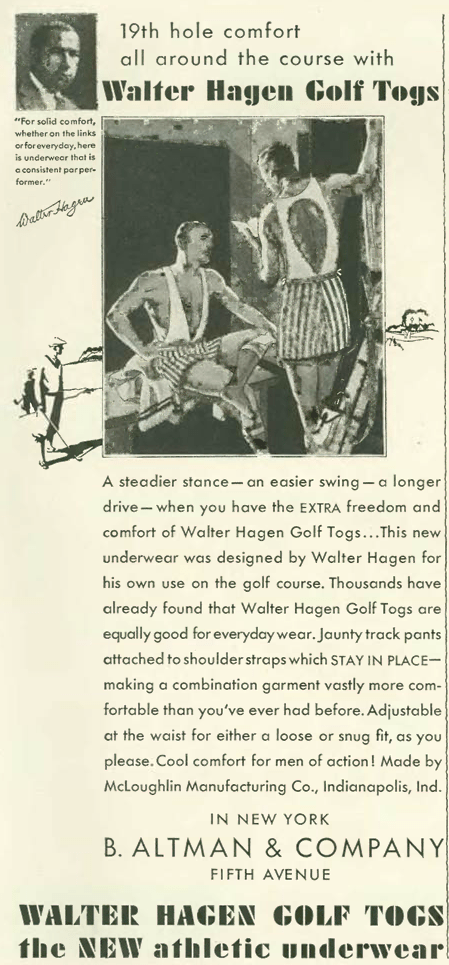

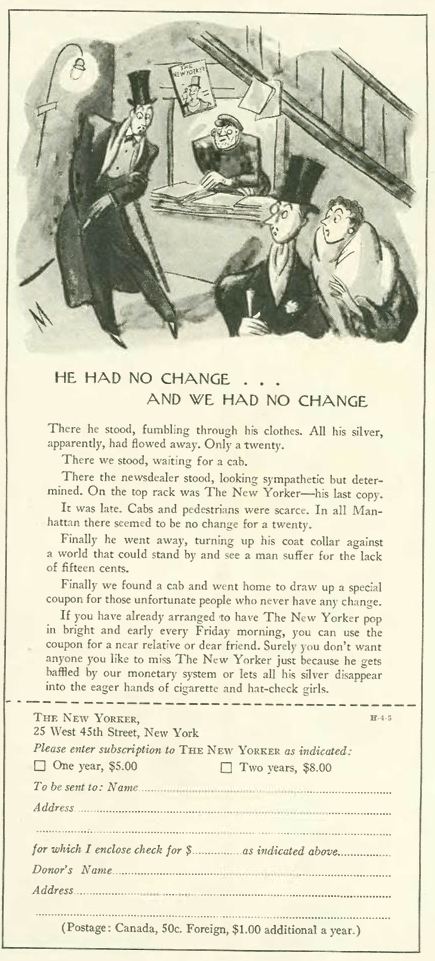

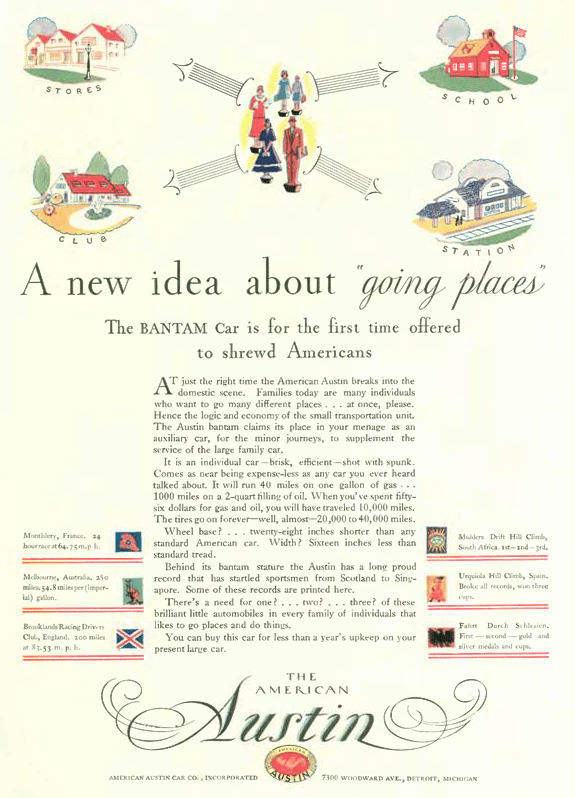

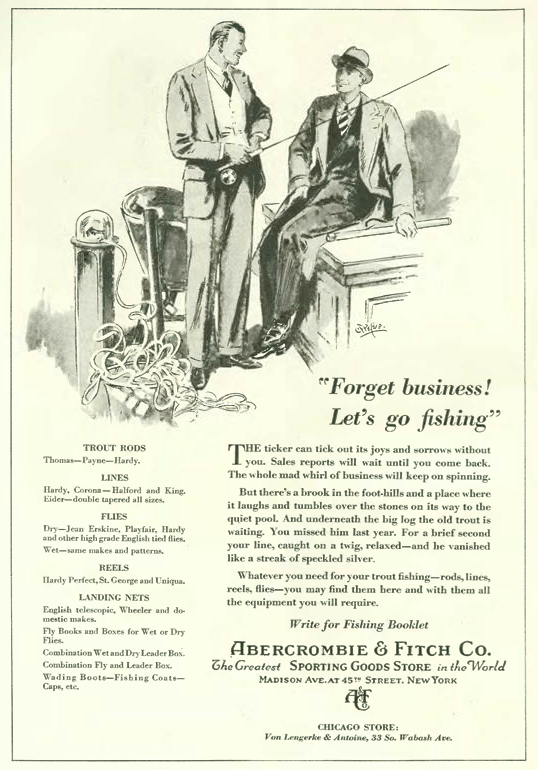

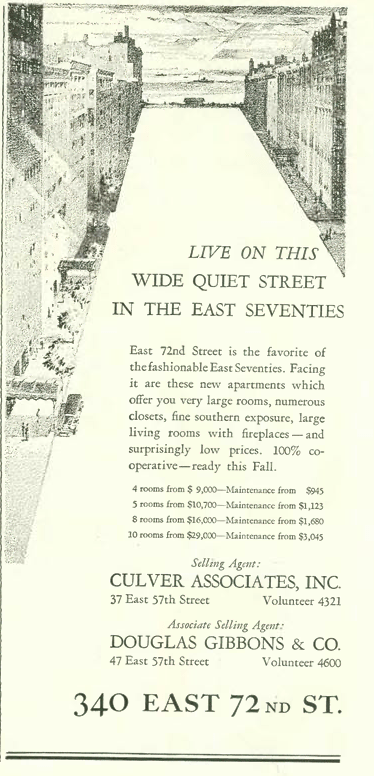

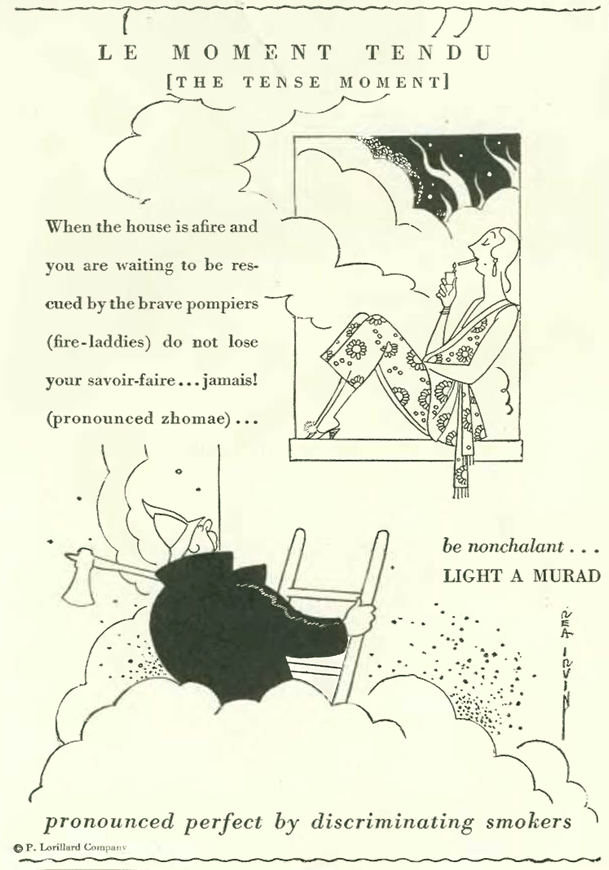

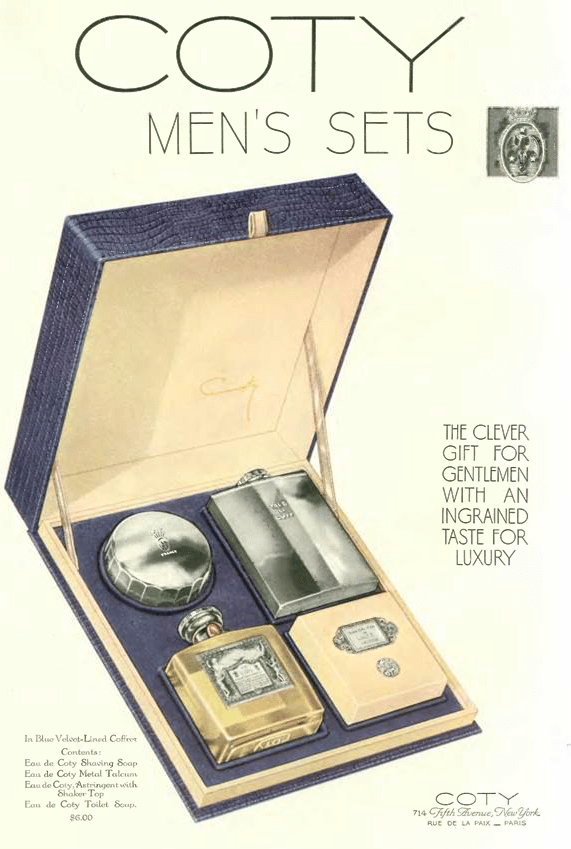

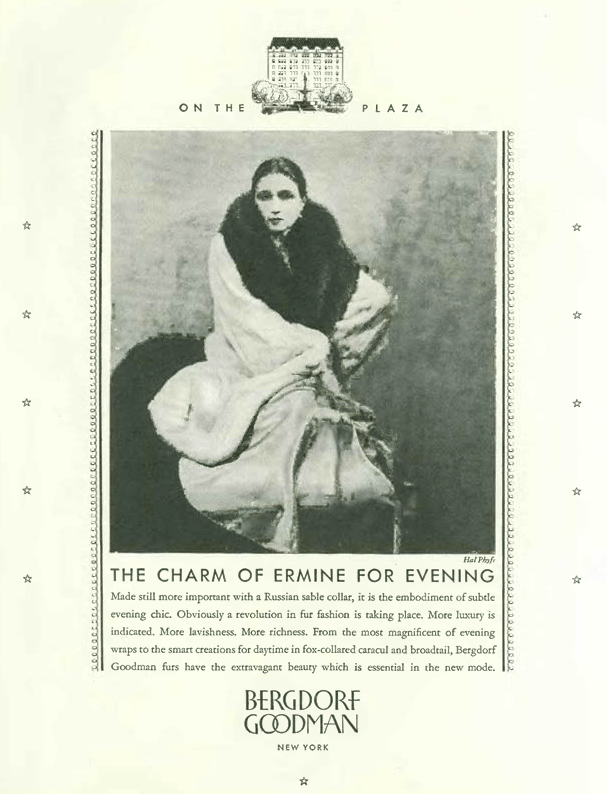

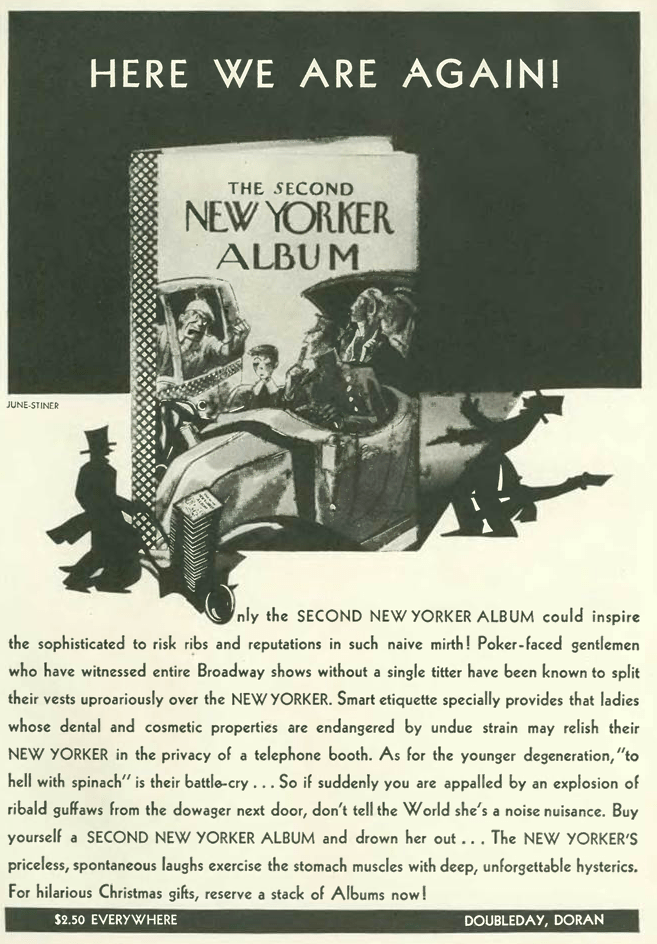

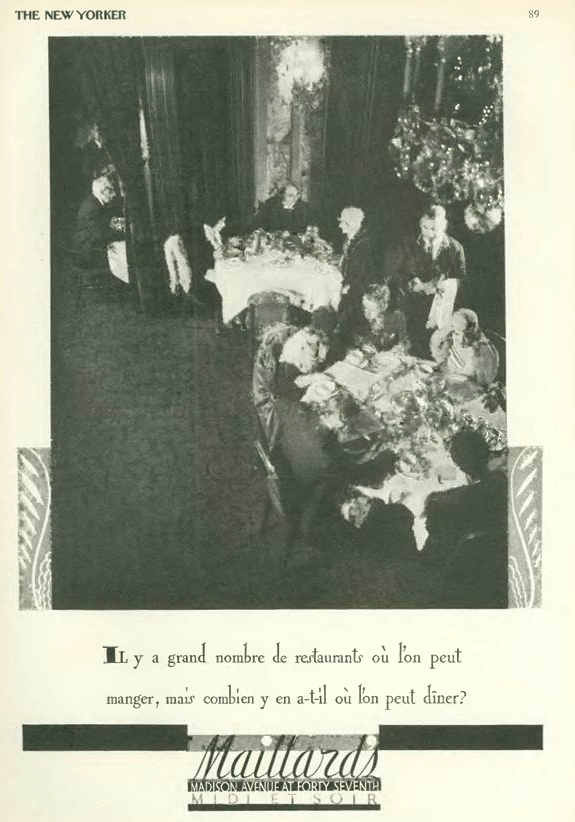

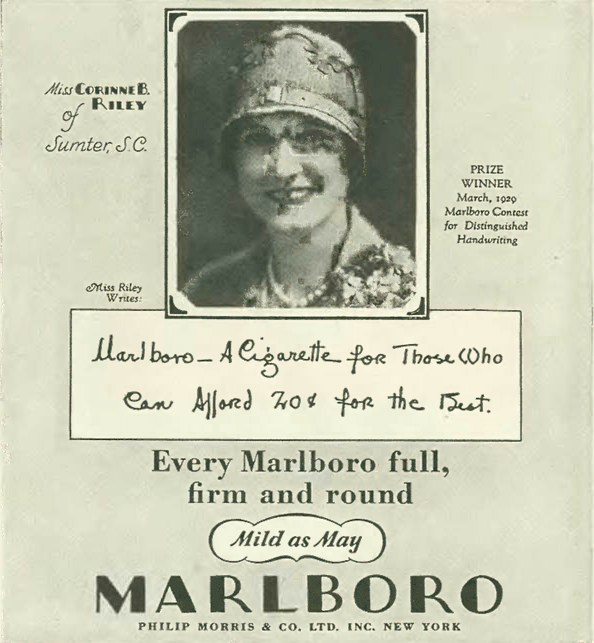

From Our Advertisers

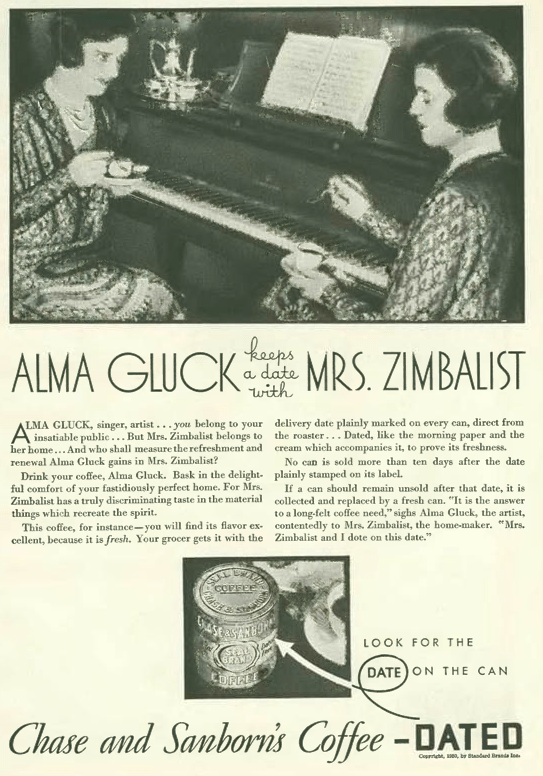

We begin with an endorsement for Chase & Sanborn coffee by the soprano Alma Gluck, wife of famed violinist and composer Efrem Zimbalist Sr. Originally I thought she was enjoying coffee with a sister in law named “Mrs. Zimbalist,” but as reader Frank Wilhoit astutely points out, the “Alma Gluck” (celebrity) and “Mrs. Zimbalist” (housewife) are alternate personae of the same individual. And now that I look at the ad again, the clothes and hair styles are identical. I will try to locate a clearer image of the ad…

…and from the makers of White Rock we have a group of swells and their airborne friends enjoying some bubbles that are doubtless mixed with illegal hootch…

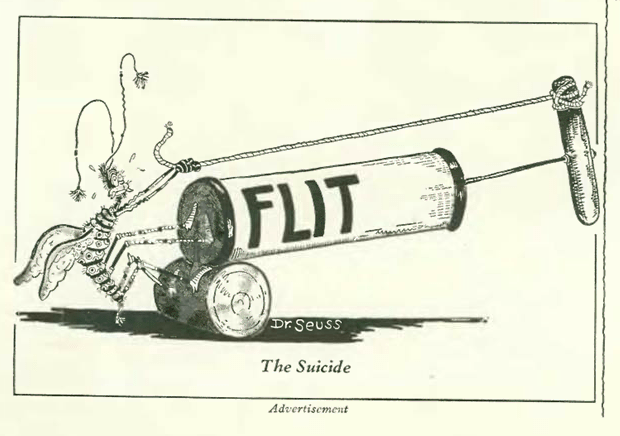

…Dr. Seuss continued to offer his artistry on behalf of Flit insecticide…

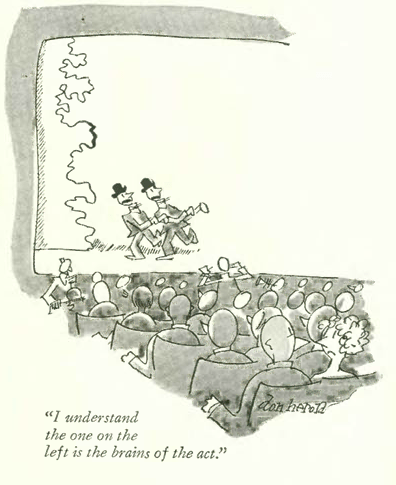

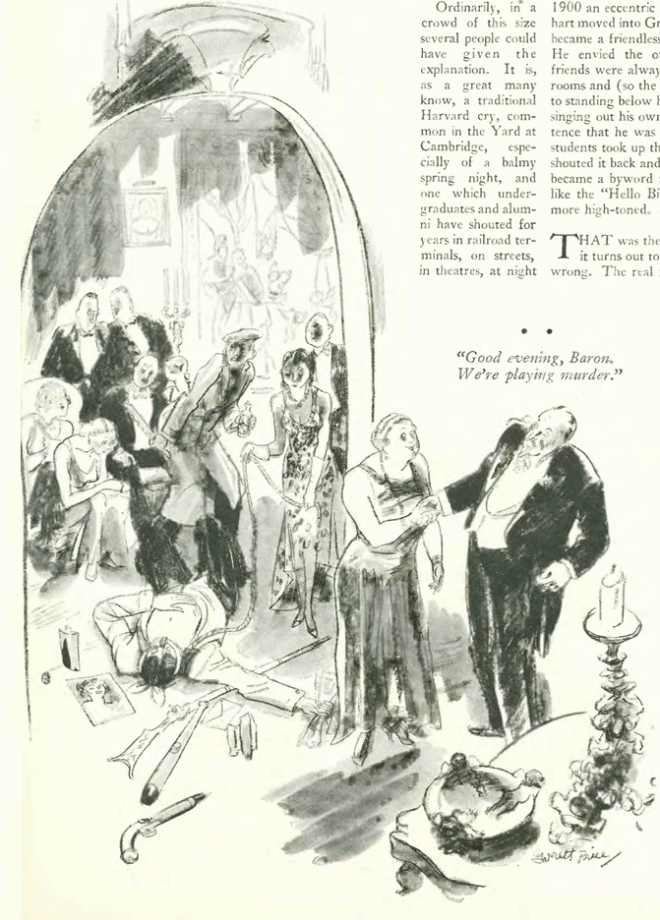

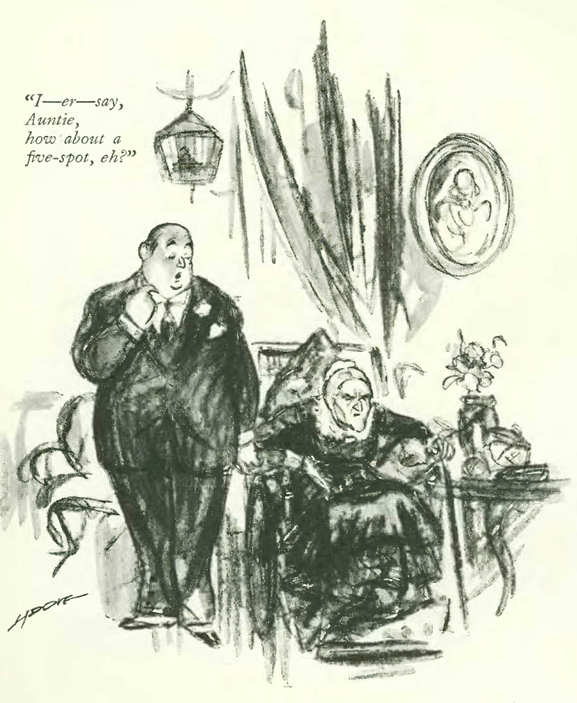

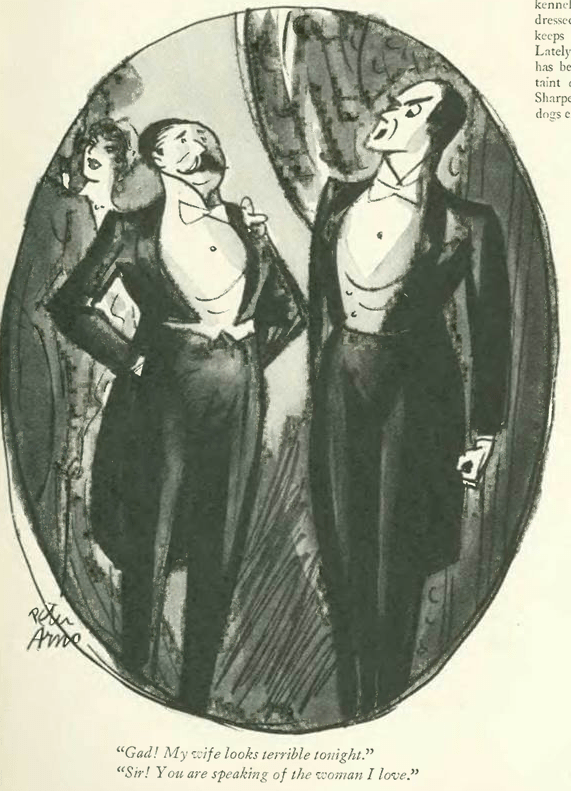

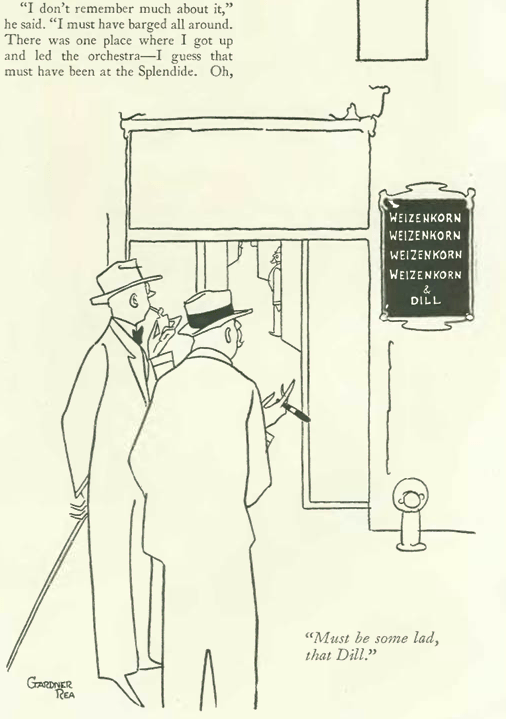

…and on to our cartoons, Peter Arno illustrated the hazards of the road…

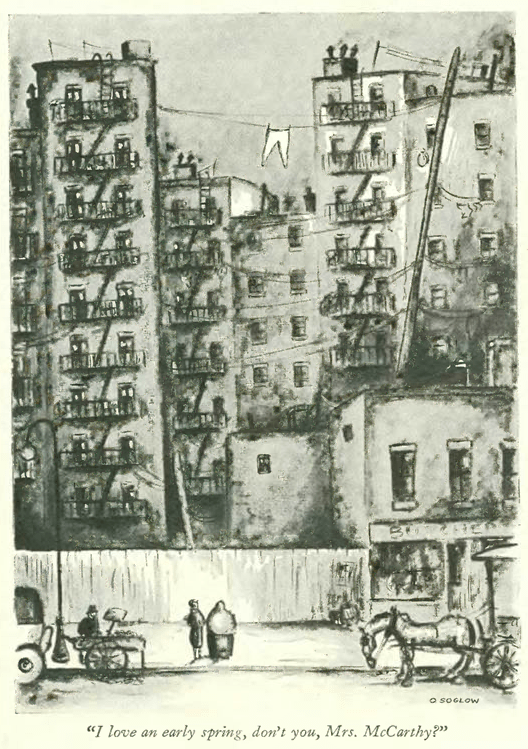

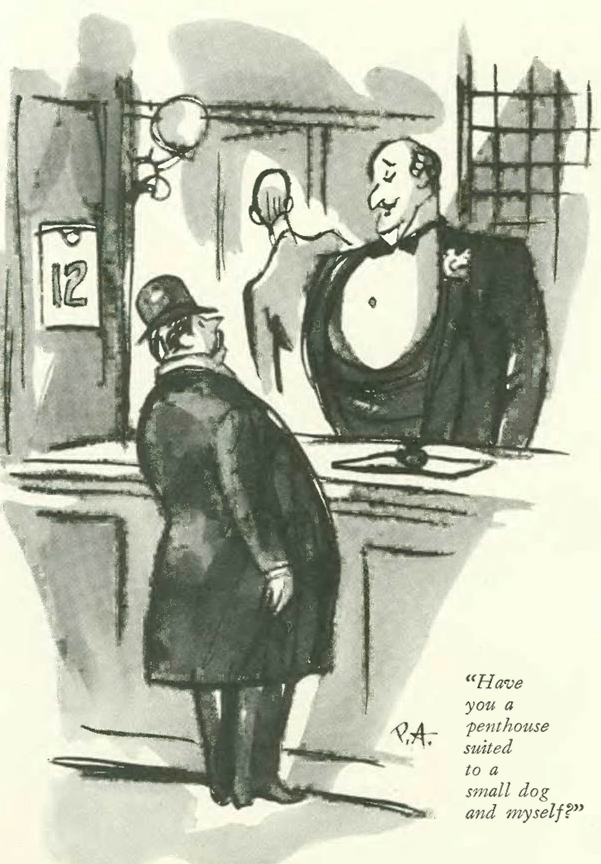

…while Leonard Dove explored the hazards high above the streets of Manhattan…

…Constantin Alajálov explored an odd encounter in a park…

…Isadore Klein mused on the tricks of mass transit…

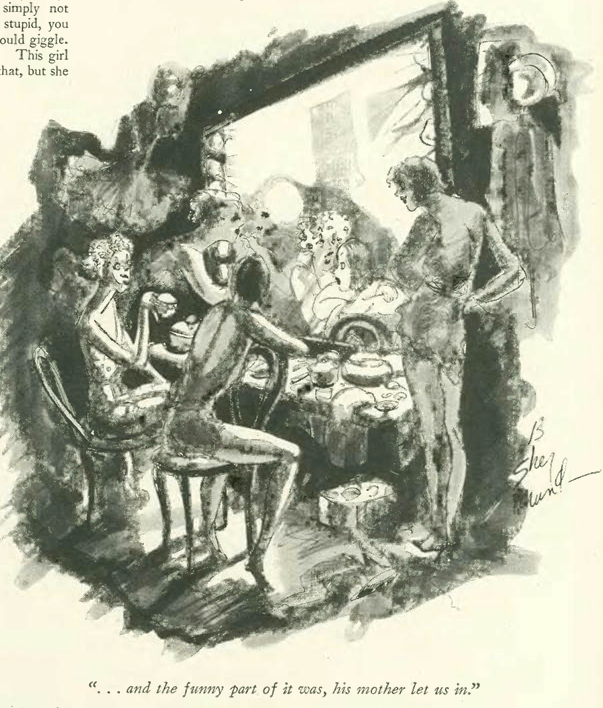

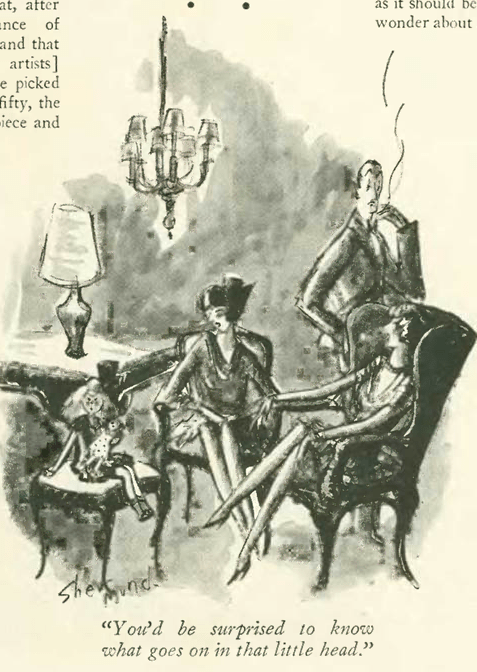

…and two from Barbara Shermund, who looked in on one tourist’s plans for a trip to Mussolini’s Italy…

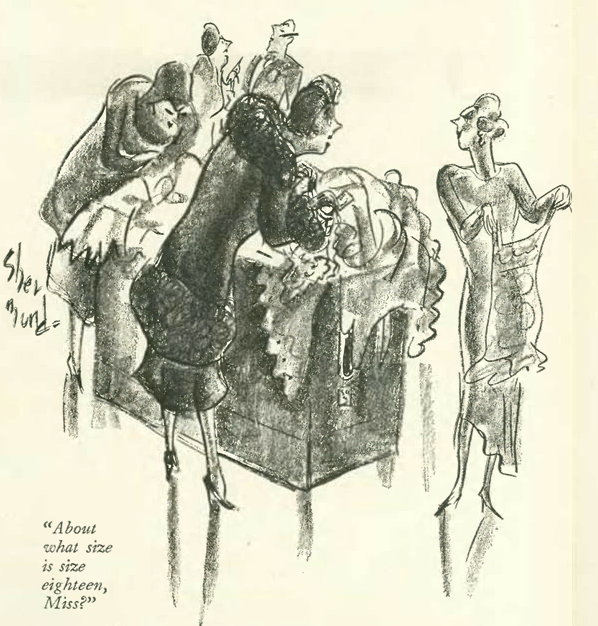

…and some helpful advice at a perfume counter…

Next Time: Red Alert…