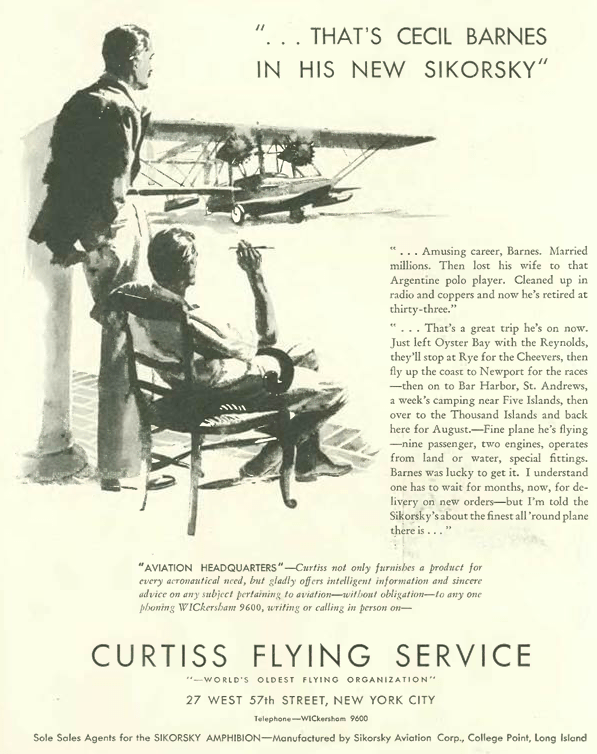

A few posts ago (the April 11 issue) I wrote about E.B. White’s love of flying, and how his (and the nation’s) exuberance for aviation suddenly came crashing down along with Knute Rockne’s plane in a Kansas wheat field.

The death of the famed Notre Dame football coach had White pondering a new, safer path for aviation that seemed to be embodied in a contraption called the autogiro. White had previously written about the potential of the autogiro back in 1929 (Dec. 7 issue). Half-helicopter and half-airplane, it was considered not only safer, but easier to fly, possibly opening up the sky to everyday commuters.

On a windy day White boarded the autogiro at an airport “in awful Queens” — most likely the current site of La Guardia — and filed this report for the “A Reporter at Large” column:

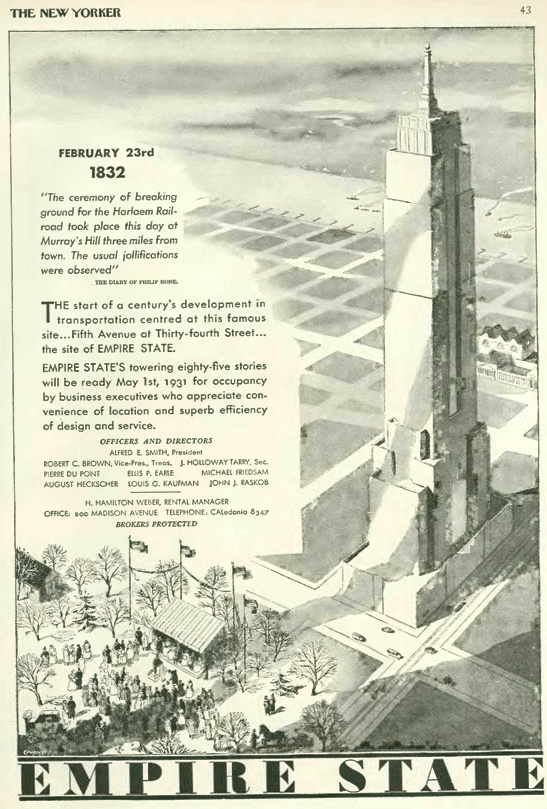

In the article, White referenced this Pitcairn Autogiro ad from the April 25, 1931 issue. No doubt the folks at Pitcairn had the Rockne accident in mind when they touted the safety of their craft, which seemed impossible to crash.

White wasn’t the only one enthused about the autogiro. It was the darling of modernist architects and futurists of 1920s and 30s, who saw the flying machine taking its place alongside the automobile in the house of the future.

Prompted by a New York Times editorial, White pondered the day when the air would be thick with personal aircraft:

White offered still more observations on aviation safety in his “Notes and Comment” column…

…and in the same column he also pondered the future in terms of his infant son, Joel White:

Sadly, Joel didn’t quite make it to the turn of the century — he died in 1997. He did, however, have a successful life as a noted naval architect and founder of the Brooklin Boat Yard in Brooklin, Maine.

One more from E.B. White, this the lead item for his column which made jest of a debate at Yale over dropping the requirement for Latin. It says something to the effect that “Yale’s lead on the issue frees the rest of us to follow our fiduciary duty, toss tradition into the fire, and focus on practical matters such as traffic studies.”

* * *

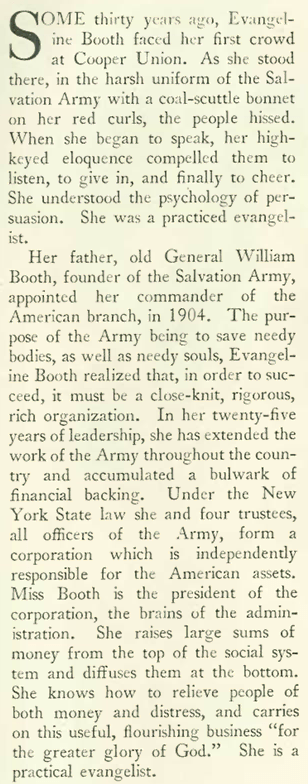

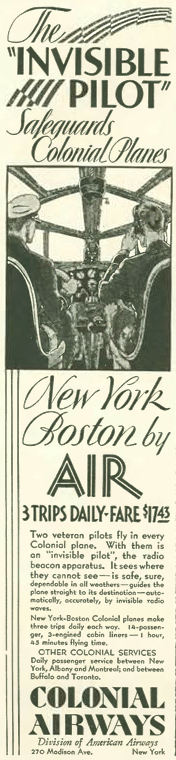

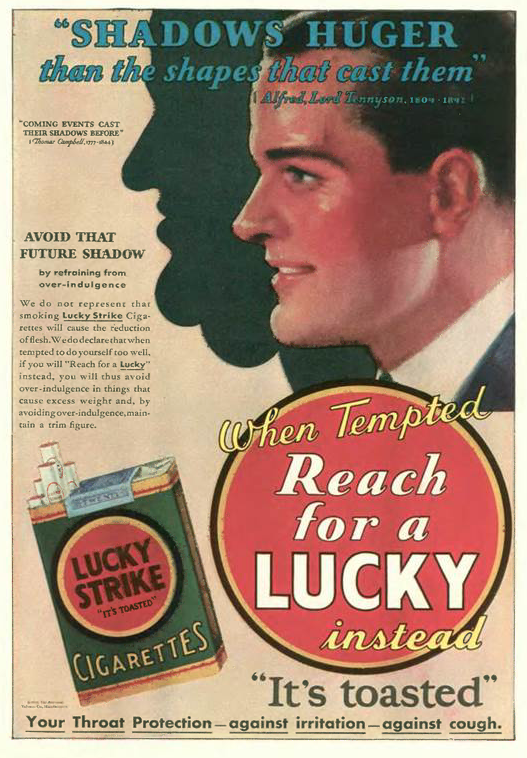

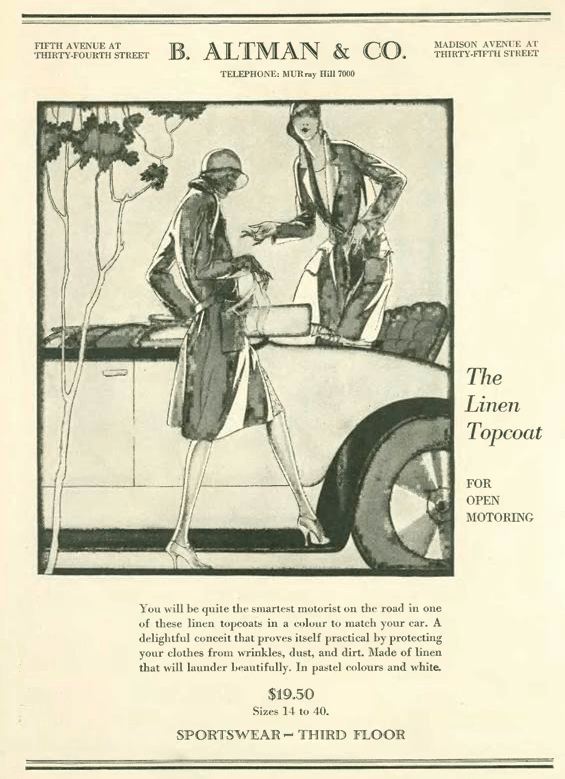

From Our Advertisers

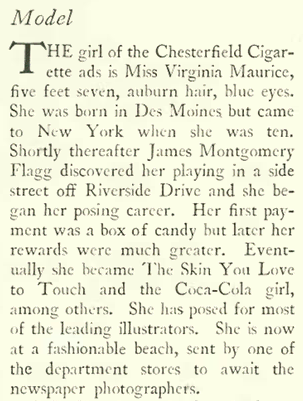

The makers of Dawn “Ring-Lit” cigarettes seemed to have a winner on their hands with a smoke you could light like a match, but I can’t find any record of the company. Most likely this was a local brand sold at nightclubs, restaurants and hotels, and not through retail…

…Murad, on the other hand, was widely available, but the brand faded as tastes moved away from Turkish-style cigarettes…Rea Irvin illustrated a long series of ads for the brand, presenting various “embarrassing moments,” including this familiar trope involving office hijinx…

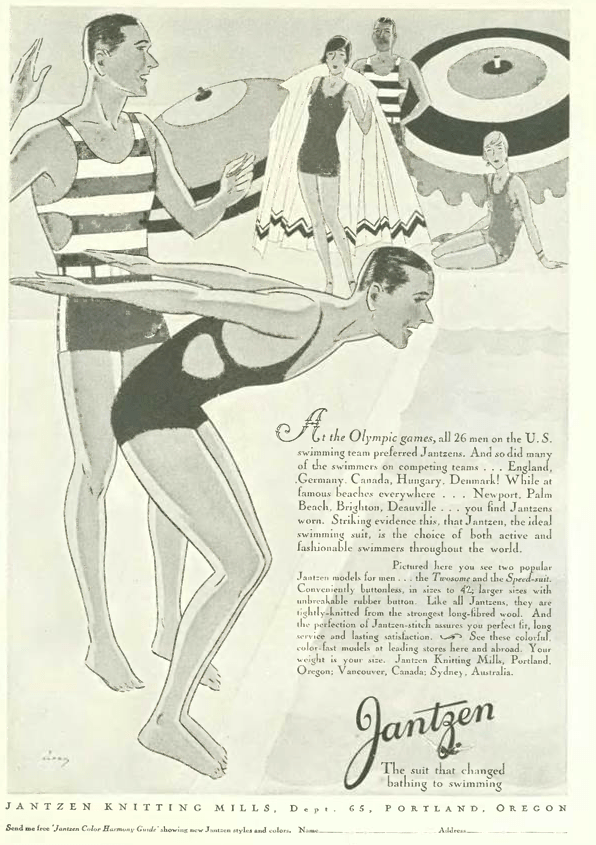

…summer was on the way, and the makers of Jantzen swimwear were establishing their brand as both the choice for athletes as well as the fashion-conscious…

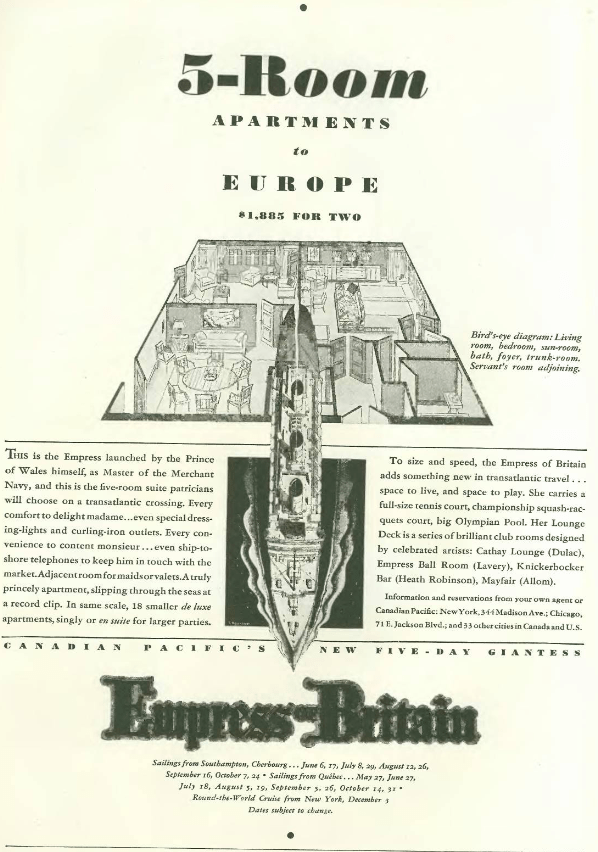

…and you might have packed a Jantzen or two for this around-the-world cruise on the Empress of Britain, arranged through Canadian Pacific. Your fare, if you wanted an “apartment with a bath,” would set you back $3,950, or a cool $63,000 in today’s currency…

…if the cruise was too rich for your budget, perhaps you could put your money toward a durable good like a GE all-steel refrigerator. Note how GE contrasted its product with the overly complicated gadgets demonstrated on stage by popular vaudeville comedian Joe Cook…

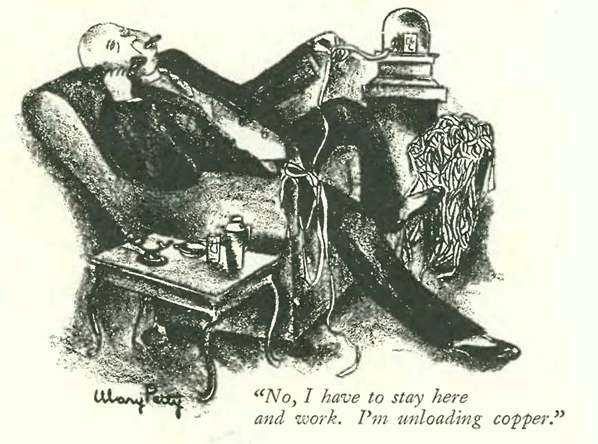

…on to the cartoons, William Steig gave us a glimpse of the important work taking place behind an exec’s closed doors…

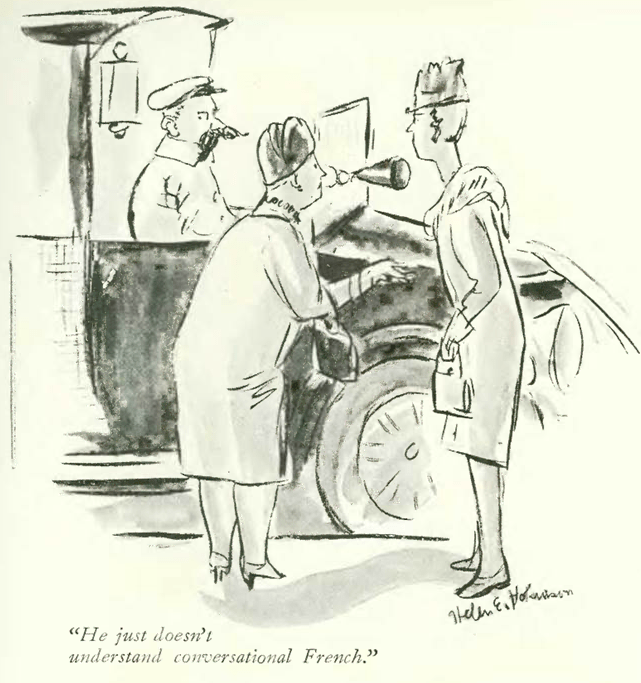

…Helen Hokinson eavesdropped on a couple’s travel plans…

…Wallace Morgan took us on a trot through Central Park…

…Perry Barlow probed labor relations in an estate garden (and a caption with The New Yorker’s signature diaeresis on the word “coöperation”)…

…and Carl Kindl gave a look into the latest maneuvers in the canned soup wars…

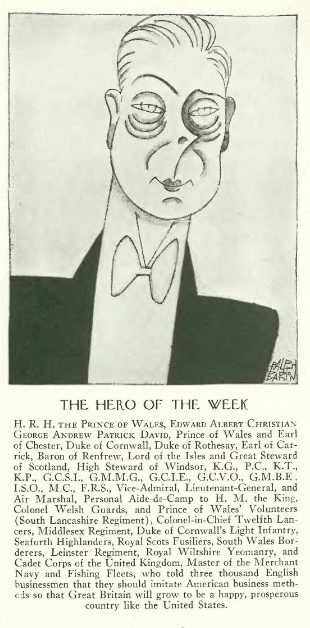

…and we end our May 23 cartoons on a sad note, with Ralph Barton’s final contribution to The New Yorker, a “Hero of the Week” illustration featuring the Prince of Wales:

On May 19, 1931, Ralph Waldo Emerson Barton, who suffered from severe manic-depression, shot himself through the right temple in his East Midtown penthouse. He was 39 years old.

From the outside one would have thought Barton had a wonderful life as a successful artist who lived in style, spent long vacations relaxing in France, and who hobnobbed with celebrities such as his close friend Charlie Chaplin.

To lose a longtime contributor and friend must have been a real blow to the staff at The New Yorker. Barton had been there from the beginning, his name appearing on the magazine’s first masthead as an honorary advisory editor:

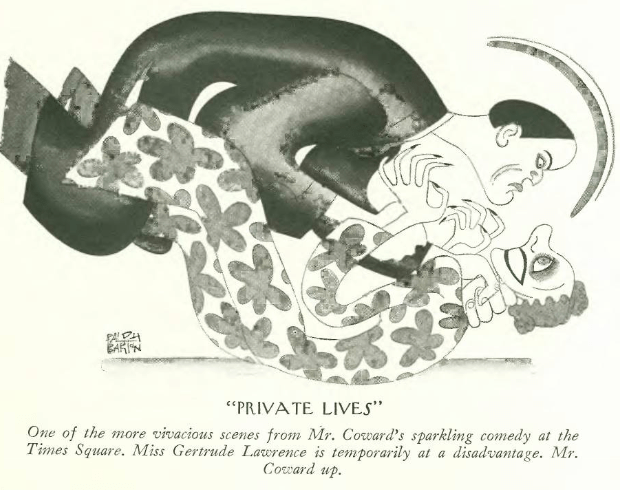

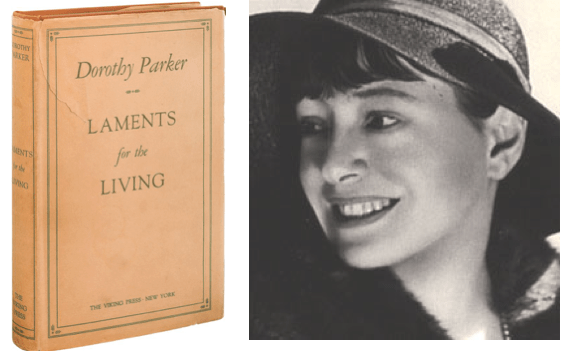

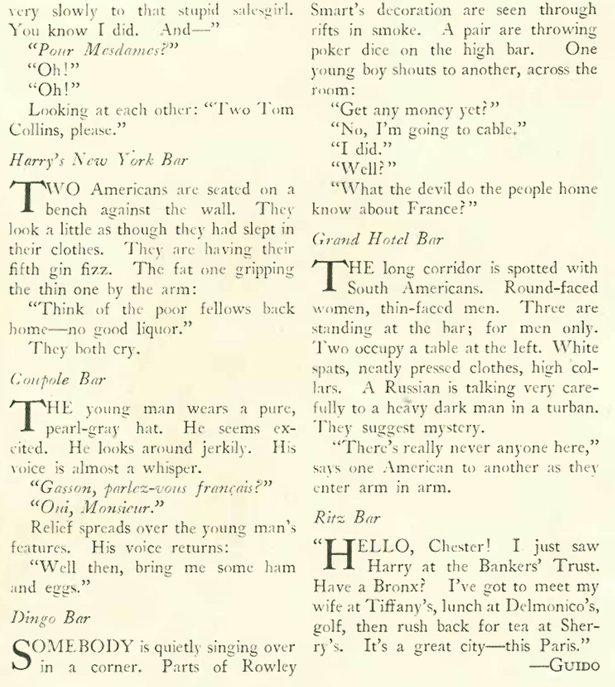

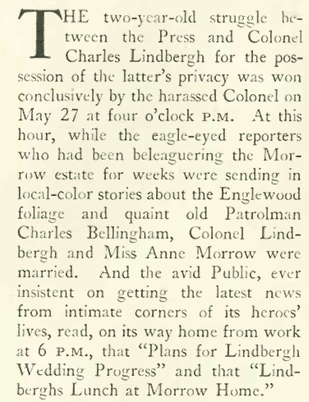

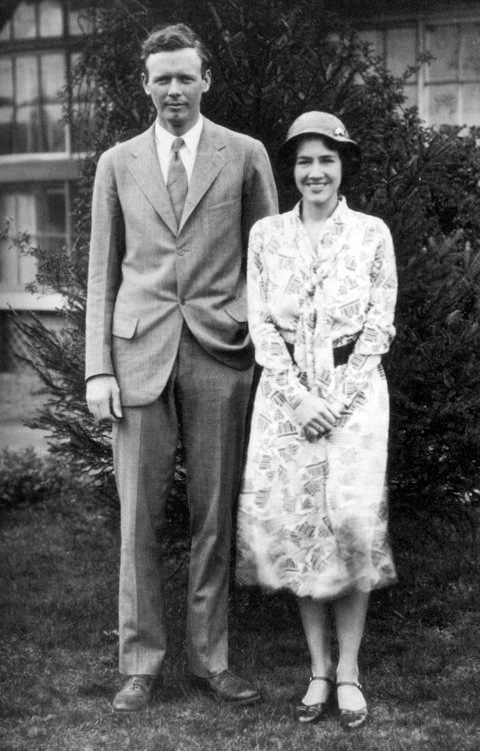

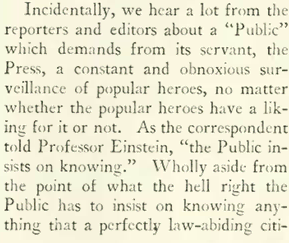

He was a prominent contributor to the magazine, from recurring features like his weekly take on the news—”The Graphic Section”—to theatrical caricatures that included clever caption-length reviews. He was married four times in his short life, most notably to actress Carlotta Monterey, his third (he was also her third marriage). She divorced Barton in 1926 and married playwright Eugene O’Neill in 1929.

In his suicide note, Barton wrote that he had irrevocably lost the only woman he ever loved, referring to Carlotta. But some speculate this claim was a final dramatic flourish, and that the end came because he feared he was on the verge of total insanity. He also wrote in the note: “I have had few difficulties, many friends, great successes; I have gone from wife to wife and house to house, visited great countries of the world—but I am fed up with inventing devices to fill up twenty-four hours of the day.”

The following issue of The New Yorker (May 30, 1931)…

…featured this brief obituary on the bottom of page 28. I like the observation on the last line…his work had the rare and discomforting tingle of genius.

* * *

The Gray & The Blue

We are reminded of the span of time and history that separate us from 1931 with this small item in “The Talk of the Town” that notes “fewer than a hundred” Civil War veterans were still alive in New York City. We just marked the 76th anniversary of D-Day, an event still 13 years into the future for this New Yorker writer:

* * *

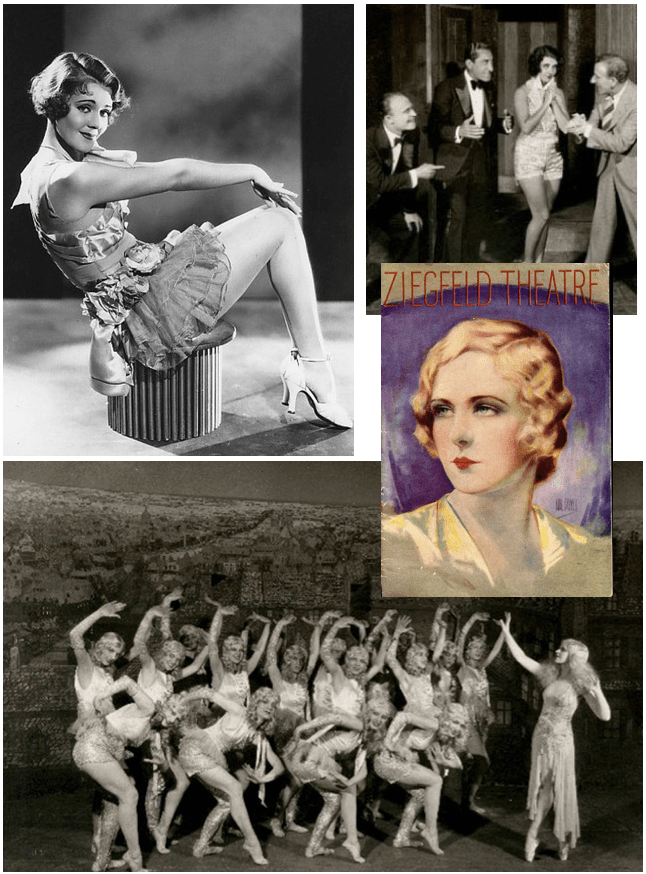

From Our Advertisers

American brewers could sense the tide was turning on Prohibition laws, among them Augustus Busch, who took out a full page ad featuring “An Open Letter to the American People” that suggested a return to beer brewing would help relieve the unemployment situation caused by the Depression — note how the ad featured a variety of non-alcoholic products, but put the alcoholic beer at the head of the line…

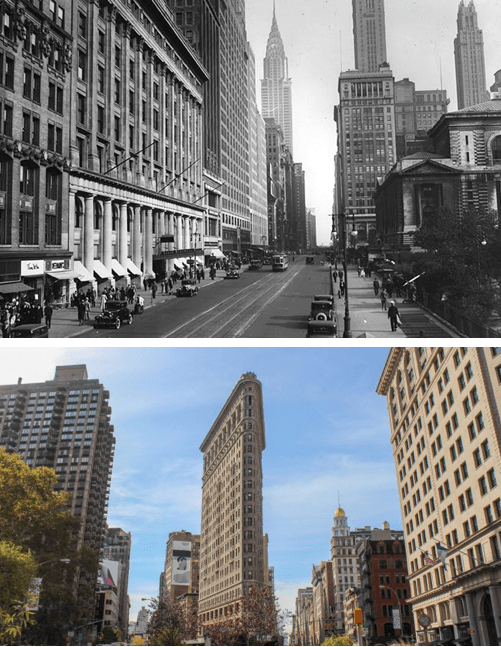

…Walking east on 24th Street past Chelsea’s London Terrace and on to Madison Square Park is one of my favorite strolls in Manhattan…there is something almost cozy about walking by this massive building, once the largest apartment house in the world…Electrolux found it impressive enough to pair it with their latest model refrigerator…

…a photo of London Terrace I took in December…

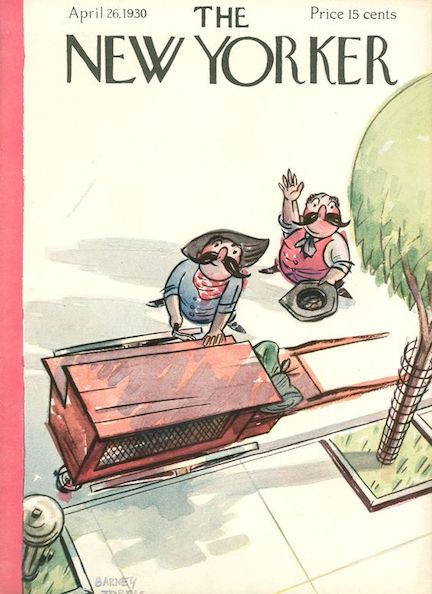

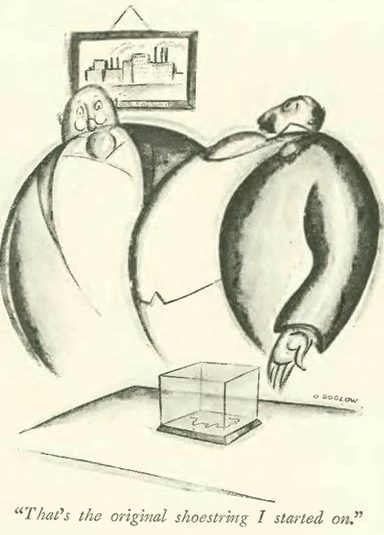

…on to our cartoons, we begin with Otto Soglow’s Little King…

…Richard Decker gave us another familiar comic trope, the postman and the housewife…

…Helen Hokinson eavesdropped on some small talk…

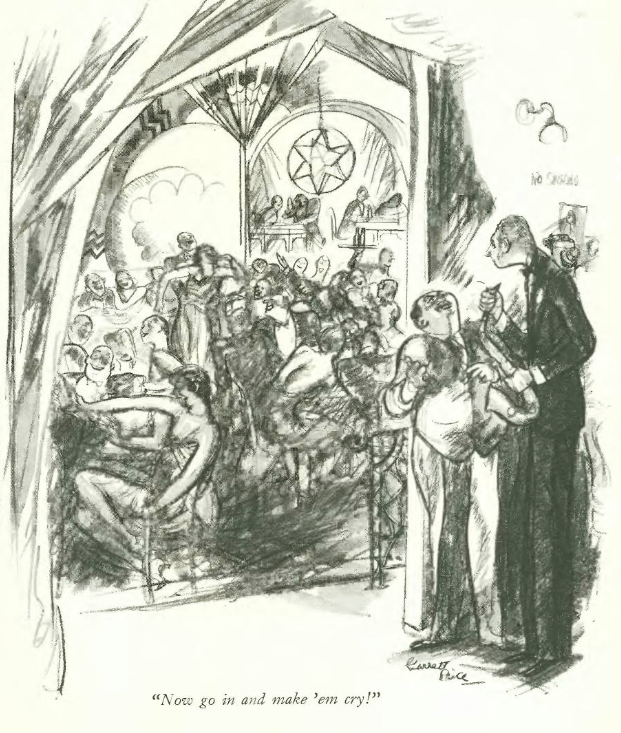

…Garrett Price explored the joys of parenthood…

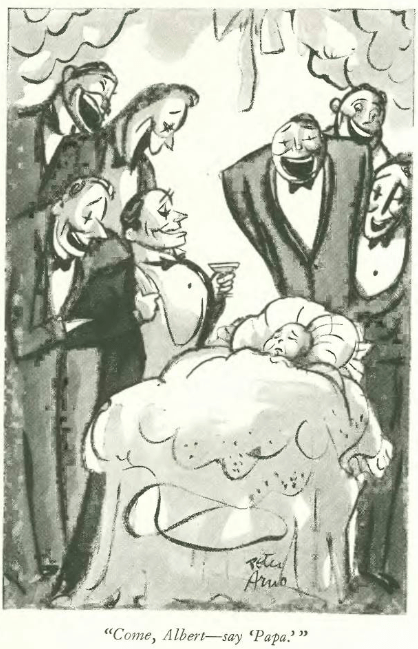

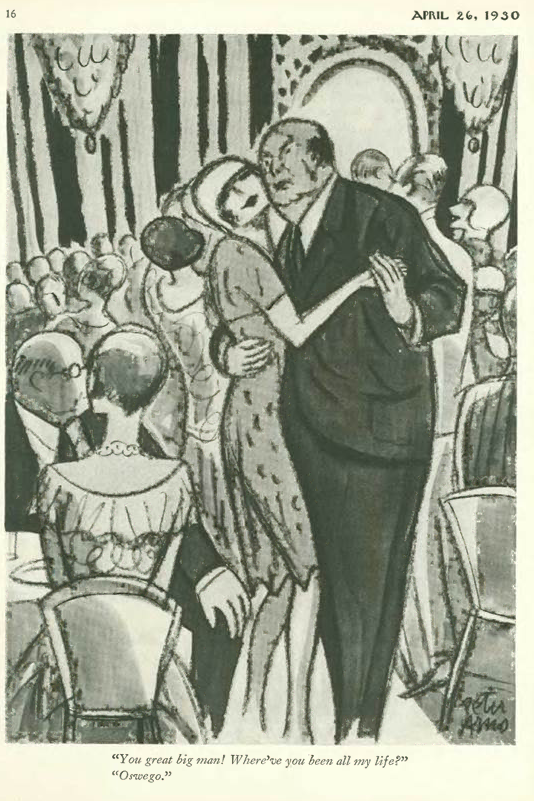

…and we close with Peter Arno’s unique take on family life…

Next Time: Rooftop Romance…