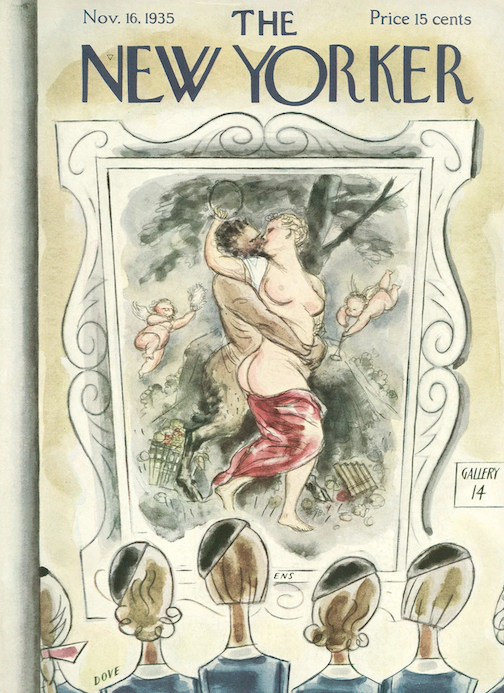

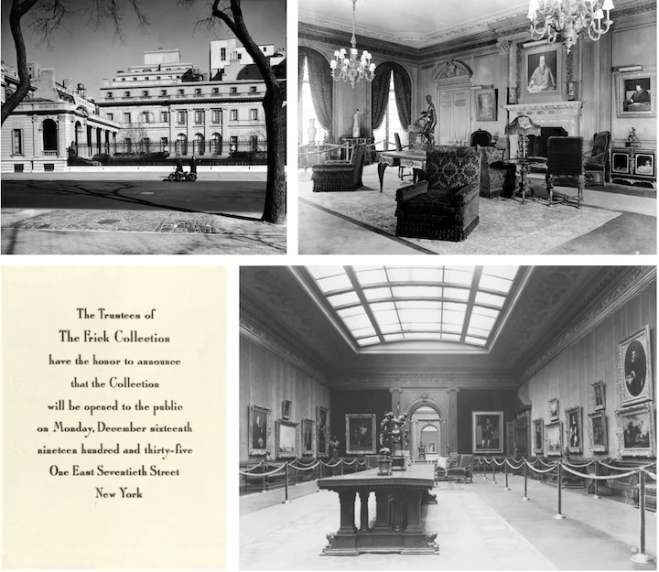

Above: Critic Lewis Mumford was not ecstatic about his visit to the newly opened Frick Collection, unhappy with the museum's crowd-control regulations that limited his view of Giovanni Bellini's masterpiece, St Francis in Ecstasy, among other things. (wikiart.org/communitydevelopmentarchive.org)

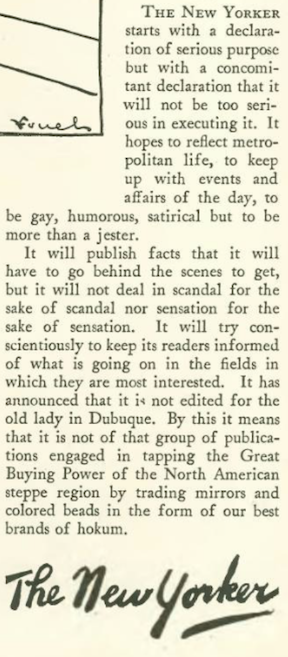

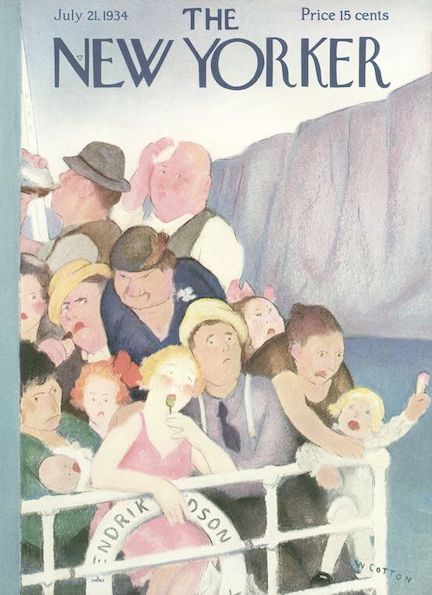

Considered one of the finest museums in the U.S., the Frick Collection on the Upper East Side of Manhattan was established in 1935 to preserve steel magnate Henry Clay Frick’s priceless 14th- to 19th-century European paintings as well as the Frick house and its furnishings. When it opened to the public on Dec. 16, 1935, museum staff distributed timed-entry tickets to prevent crowding, and therein lay the rub for New Yorker critic Lewis Mumford.

The timed tickets, along with ropes that forced visitors to follow a defined path, spoiled the museum’s debut for Mumford, who was one of its few detractors. In these excerpts Mumford addressed the crowd control measures, and criticized the furniture and other “bric-a-brac” that further served to obstruct his viewing pleasure:

The Frick’s recent renovation and expansion has also had its detractors; after enduring a long and contentious proposal review process and five years of renovation and construction, the Frick reopened to the public in April 2025. It seems most attendees appreciate the changes.

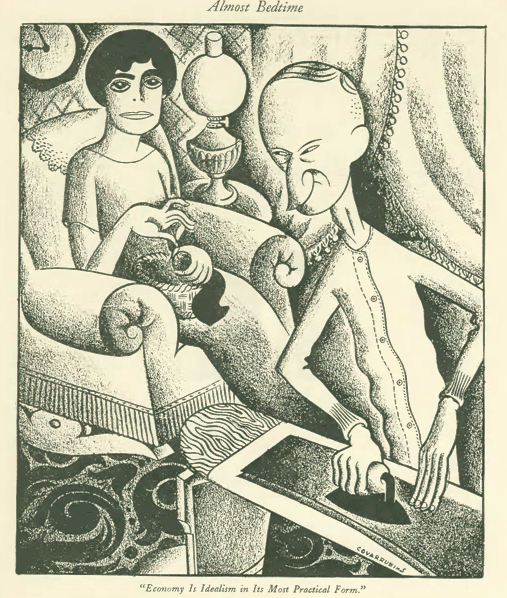

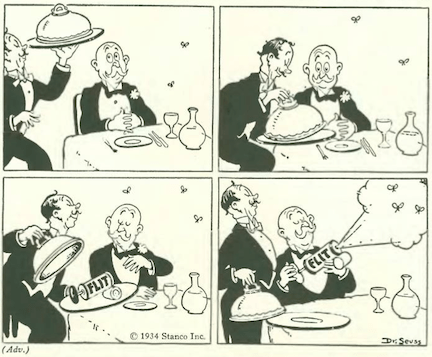

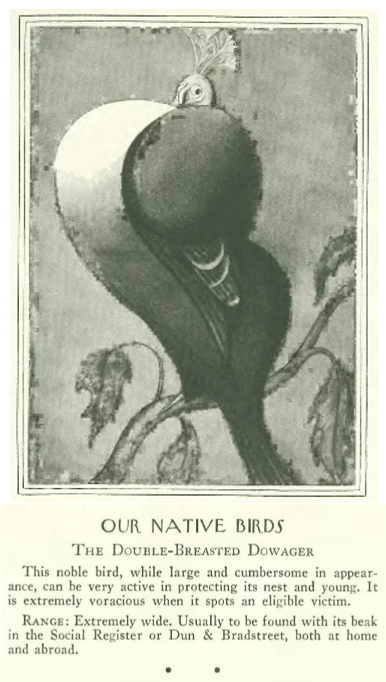

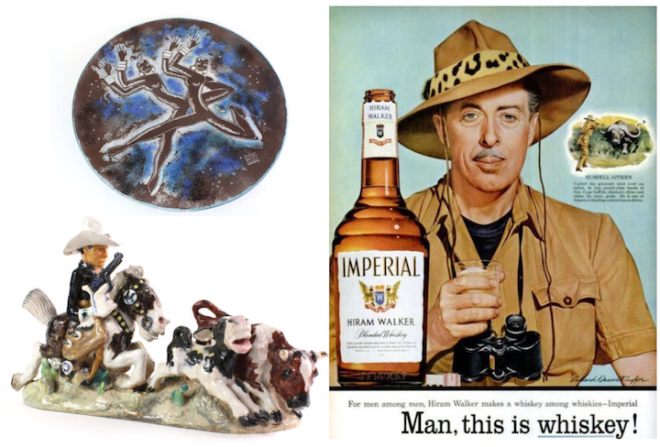

Mumford also took a look at the latest work by ceramic sculptor Russell Aitken (1910-2002), comparing his work to that of a cartoonist. Aitken was a rather odd duck in the art world, renowned both for his quirky sculptures as well as for his exploits as a big game hunter.

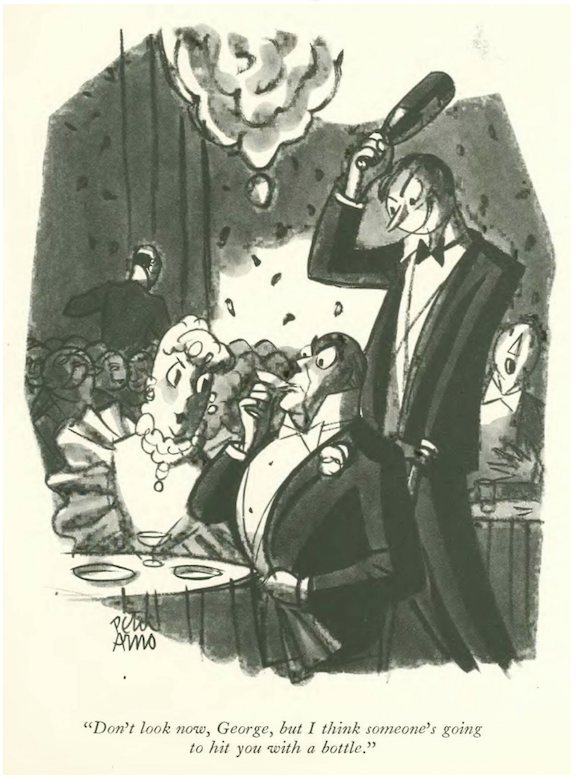

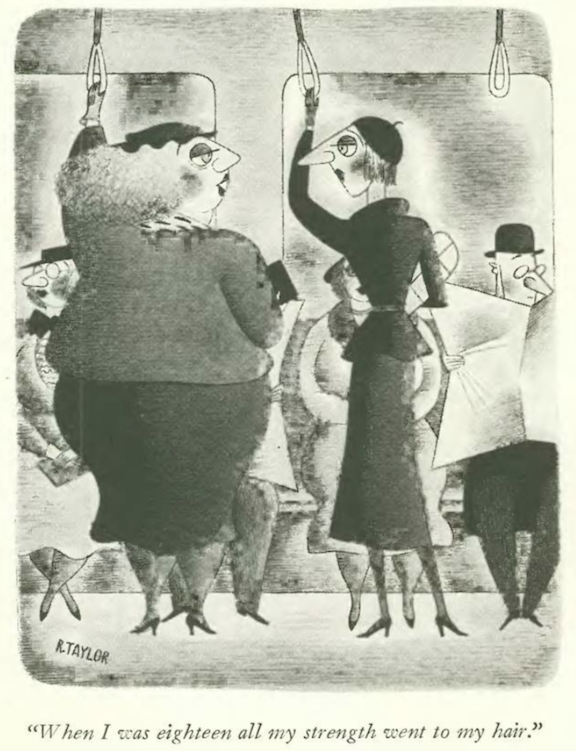

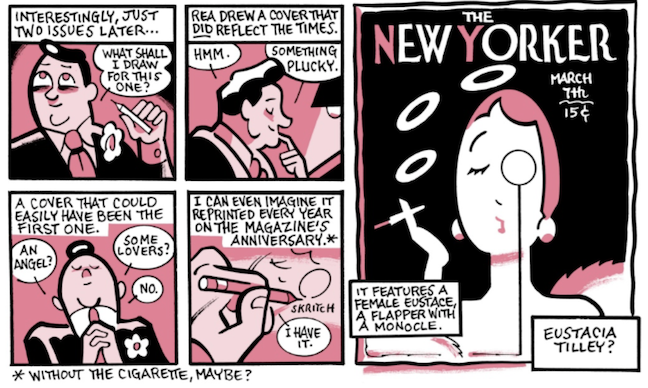

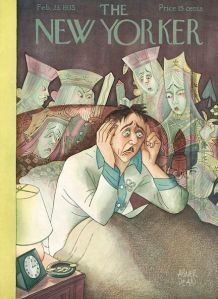

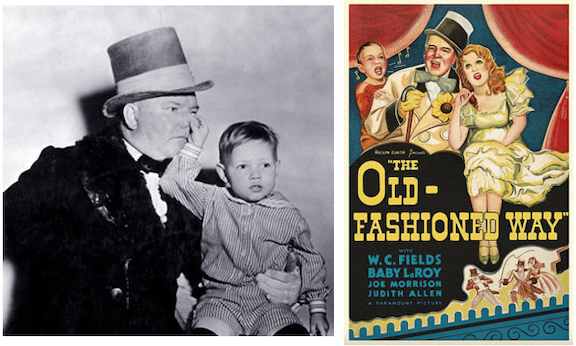

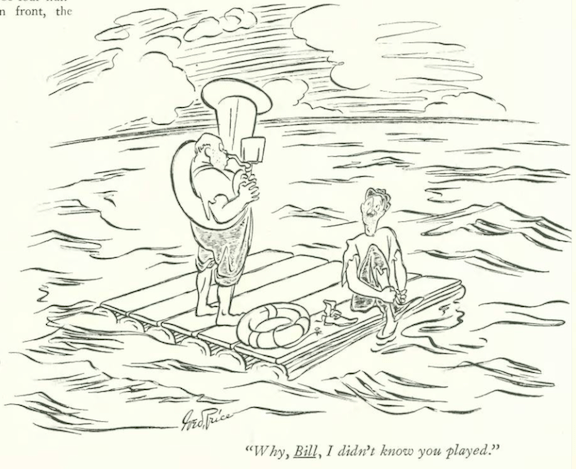

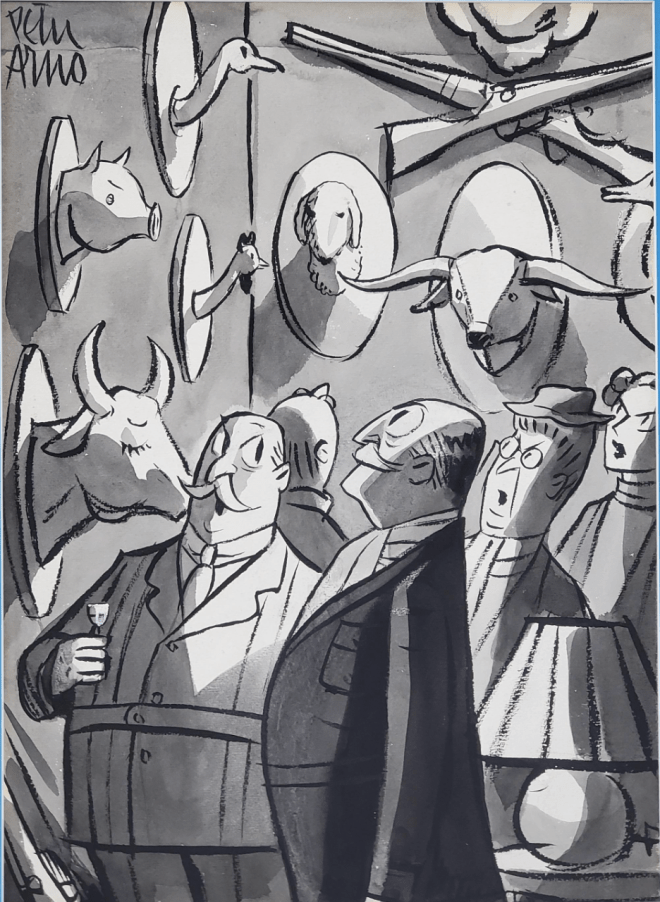

It’s always a little dicey to review the work of a colleague, but in the case of Peter Arno, Mumford had mostly praise, some of it quite high, that is except for Arno’s “white-whiskered major” which Mumford characterized as a “lazy, pat form.”

Thankfully Arno ignored Mumford’s criticism and continued to draw his “white-whiskered major.” Here he is in a delightful 1937 cartoon featured on one of my favorite New Yorker-related sites, Attempted Bloggery:

* * *

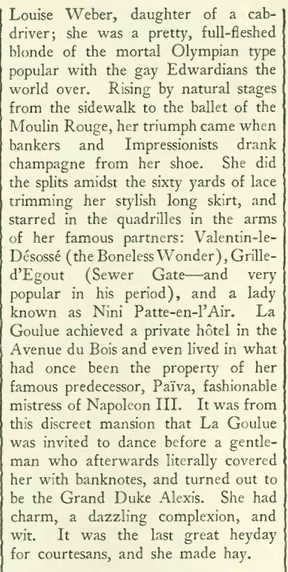

Shock of the New

E.B. White, ever skeptical of newfangled inventions, saw no reason why The New Yorker’s old ice-filled water cooler needed to be replaced by a “rattling” electric one:

* * *

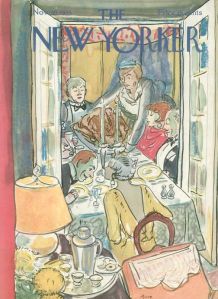

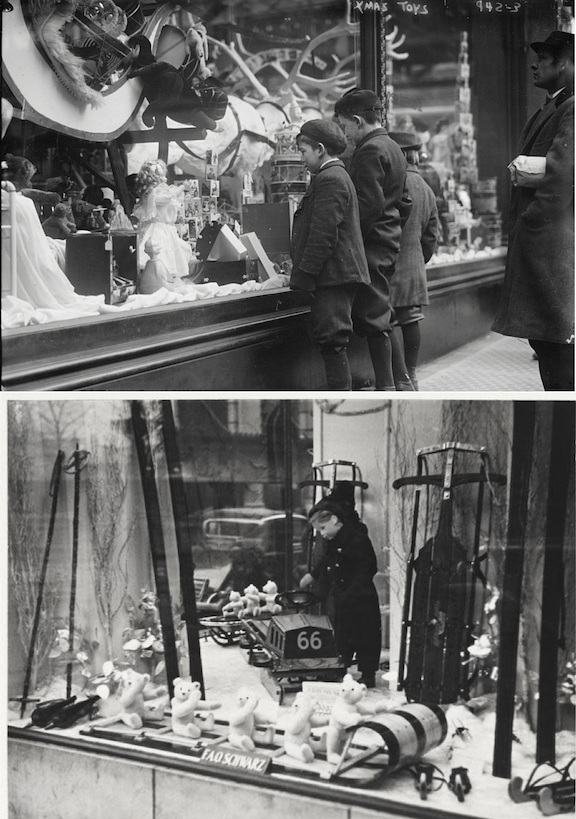

O Tannenbaum

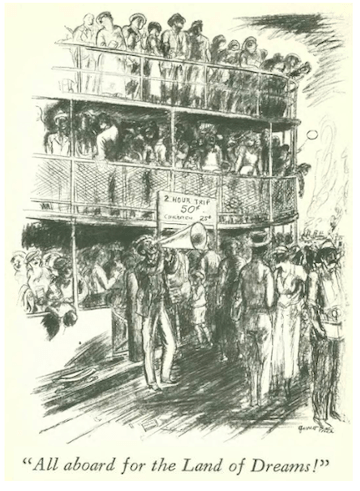

Two decades before Rockefeller Plaza raised its giant Christmas tree (or before Rockefeller Center even existed), New Yorkers gathered around a “Tree of Light” at Madison Square. “The Talk of the Town” remembered:

According to Bowery Boys History, in 1912 “this ‘Tree of Light’, mounted in cement, was such a novelty that almost 25,000 people showed up that night [Christmas Eve] to witness it and enjoy an evening-long slate of choral entertainment.” The following year, The New York Times reported that the Salvation Army took over the event, offering up “10,000 hot sausages and 10,000 cups of hot coffee” for the crowds.

The celebration was sparked by social activists seeking to draw attention to the needs of the city’s poor. On Christmas Day, 1912, the Times ran extensive coverage, and noted the charitable tone of the event in this excerpt:

* * *

Honor Roll

Joseph P. Pollard and W.E. Farbstein covered a two-page spread, listing individuals of “Special Distinction” in honor of the New Year…here is a brief excerpt:

* * *

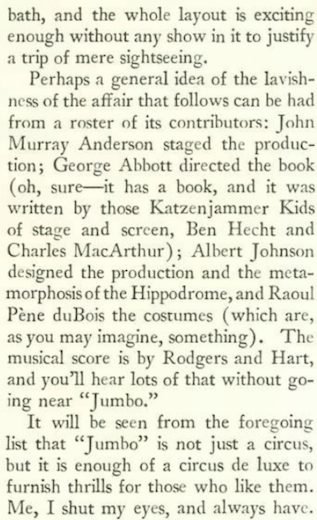

Best (and Worst) of Broadway

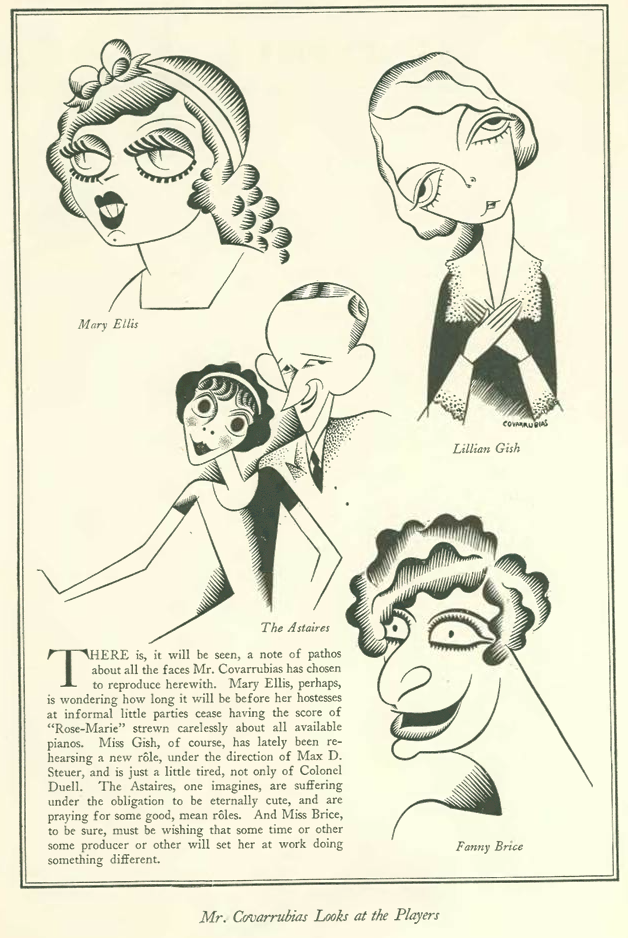

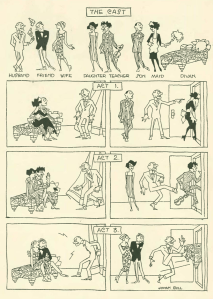

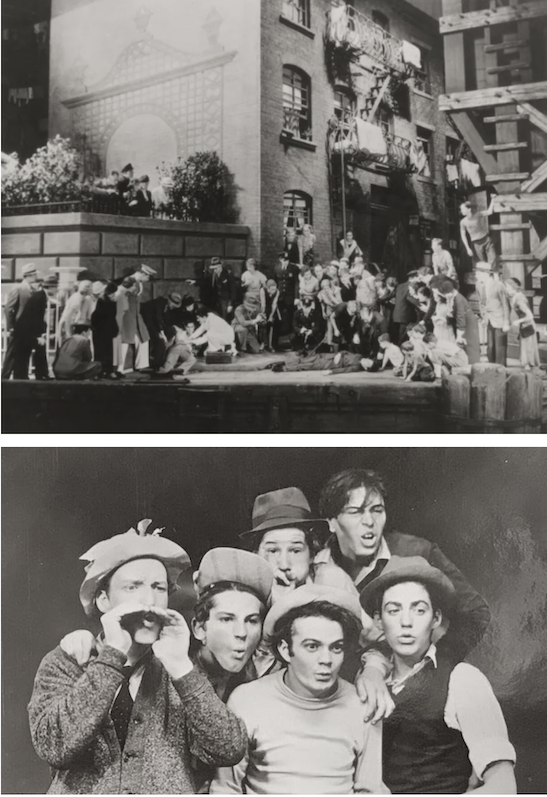

Robert Benchley reviewed the hits and misses of the fall Broadway season, and admitted he had become something of a softhearted theatre critic after spending six months in Hollywood.

* * *

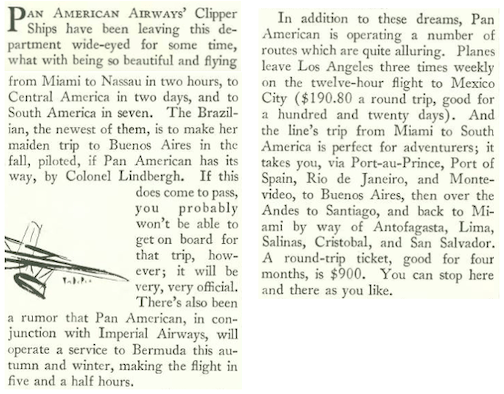

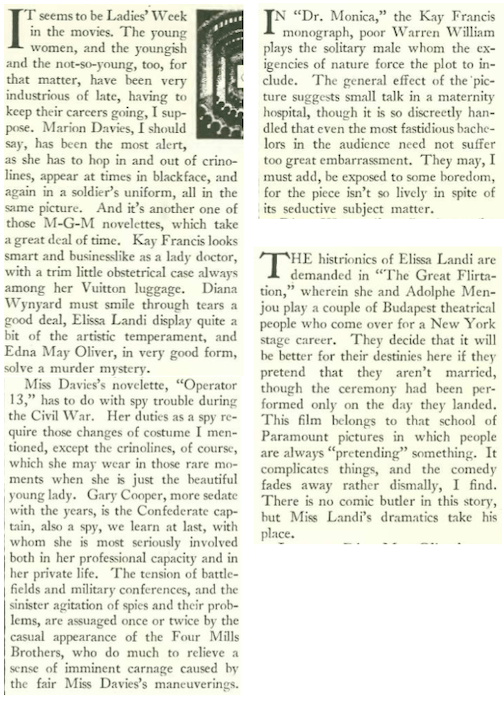

At the Movies

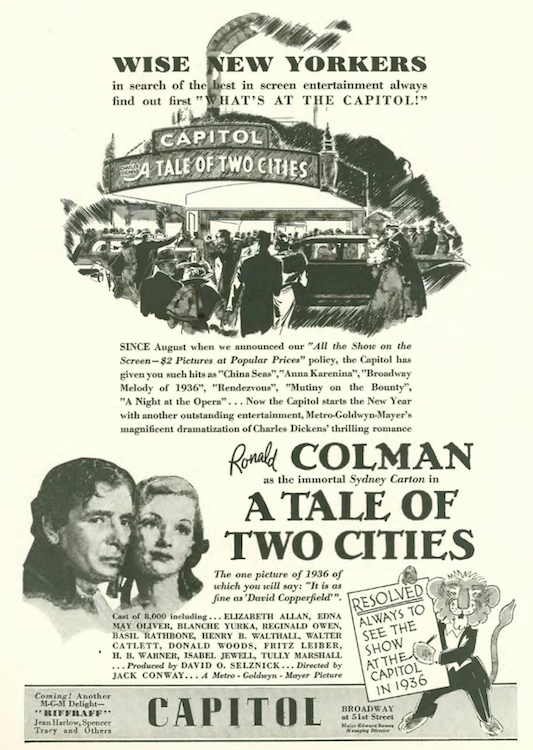

New Yorkers could nurse their holiday hangovers with a variety of films, ranging from the “very pleasant” The Perfect Gentleman to the “overdressed” Captain Blood, which featured a young Errol Flynn as a rather gentle pirate. As for the late year’s most anticipated film, A Tale of Two Cities, critic John Mosher found a few bright spots between his yawns, including praise for Blanche Yurka’s standout performance as Madame DeFarge.

If piracy and revolution were “too much for your holiday nerves,” Mosher suggested the latest Shirley Temple film, The Littlest Rebel, featuring the superstar moppet dancing her way through the Civil War (and, unfortunately, performing a scene in blackface). Also on tap was the the musical comedy, Coronado.

* * *

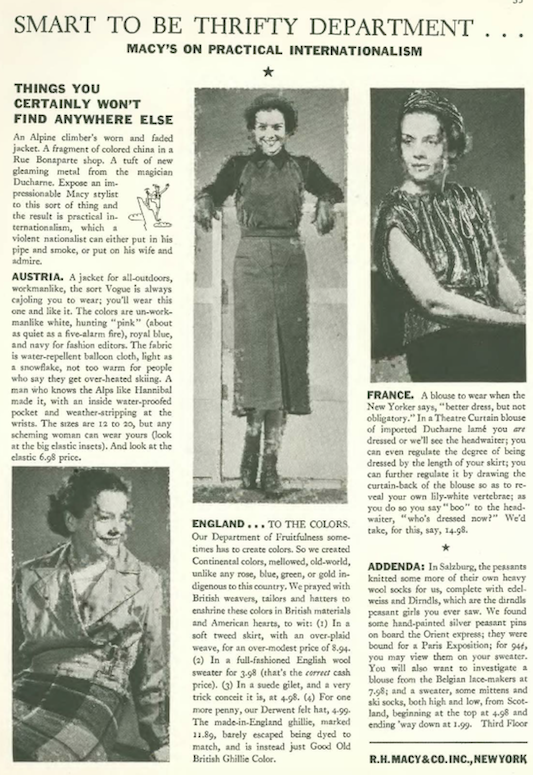

From Our Advertisers

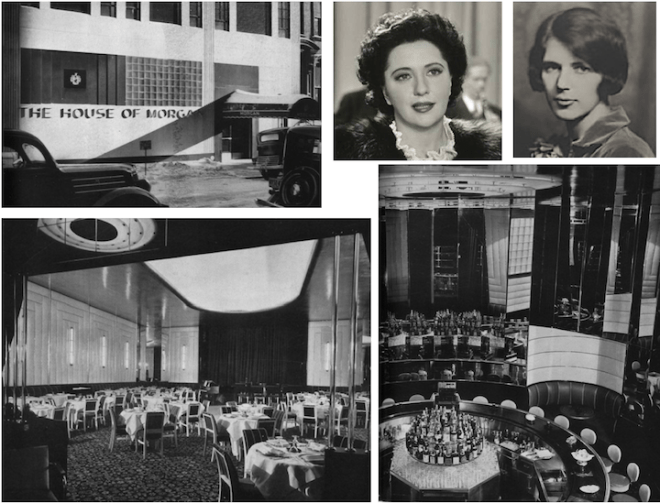

We look in on our advertisers, beginning with this from Stage magazine…the actor portraying Nero is likely from the play Achilles Had a Heel, which closed after just eight performances…

…John Mosher wasn’t wowed by MGM’s A Tale of Two Cities, even if the Capitol Theatre promised a spectacle with “a cast of 8,000″…

…this back of the book ad promised entertainment by “Society Amateurs” selected from the “Sunday Evening Debut Parties”…

…the brewers of Guinness promoted the health benefits of their product for the New Year…

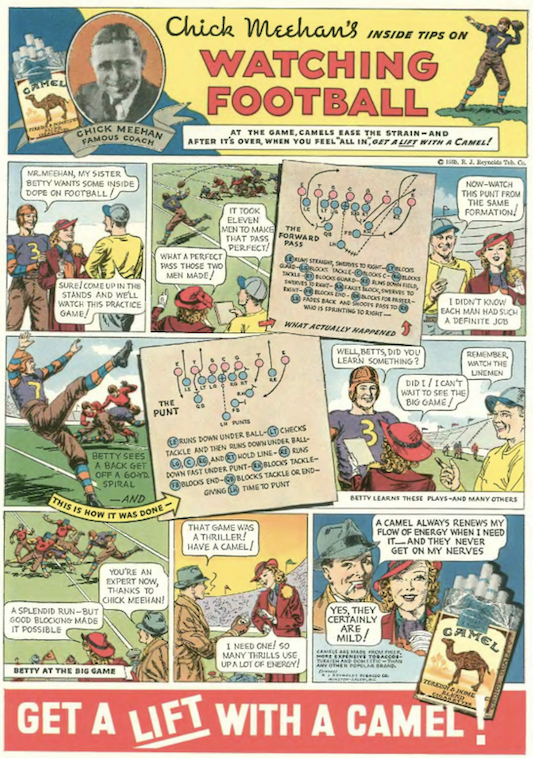

…and the makers of Camels continued to print testimonials touting the invigorating effects of their cigarettes…

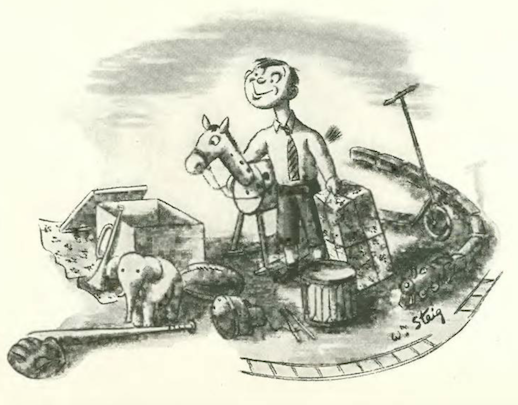

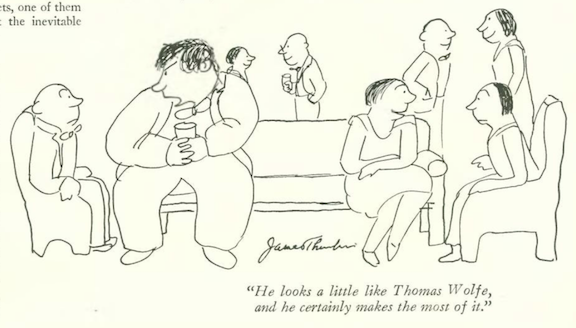

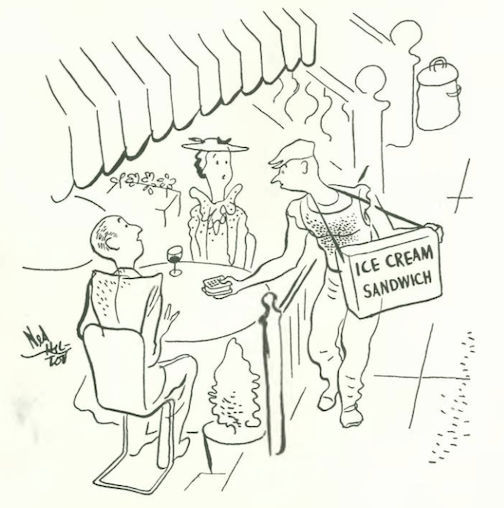

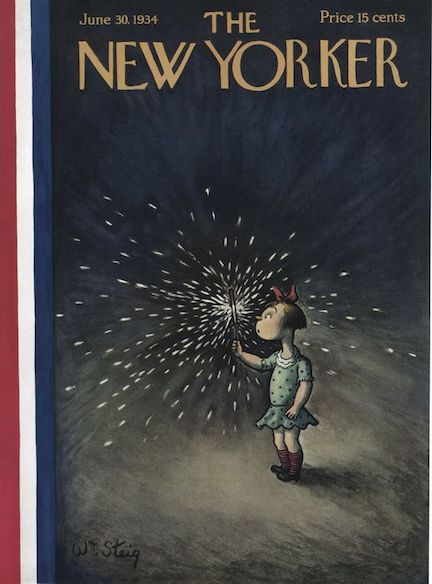

…on to our cartoonists, with William Steig taking stock of the Christmas haul…

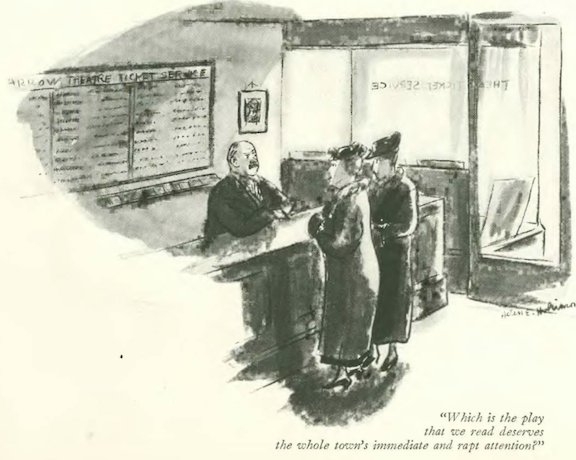

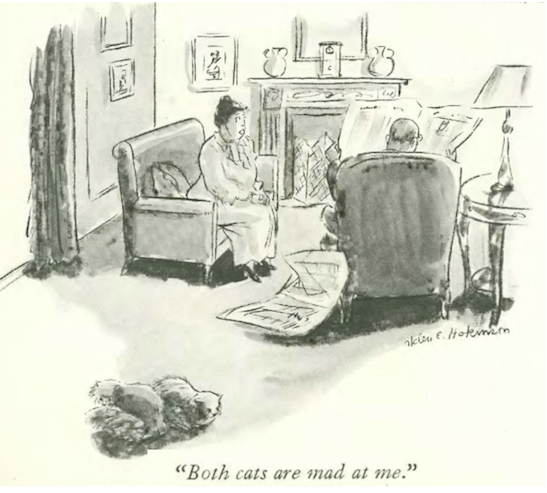

…Helen Hokinson’s girls were looking for the hottest show in town…

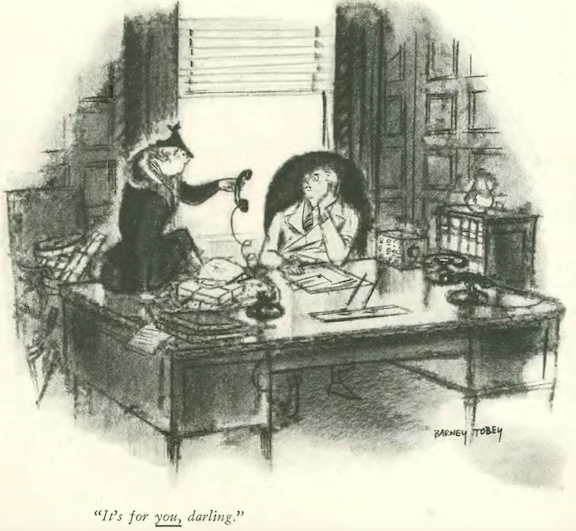

…Barney Tobey was the latest cartoonist to take a shot at the boss-secretary trope…

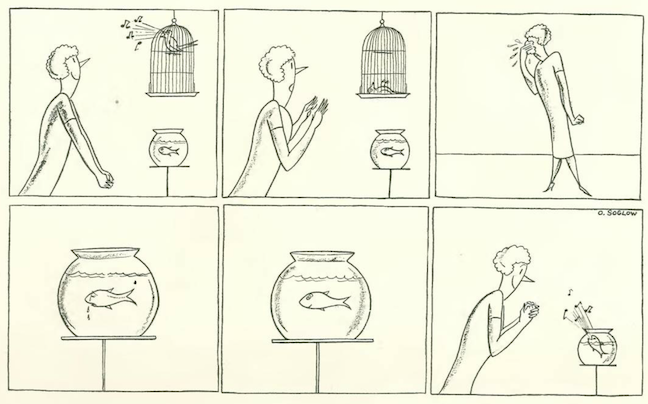

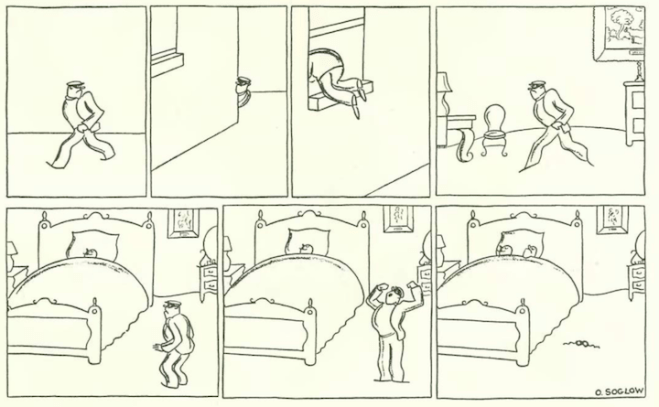

…Otto Soglow gave us a singing fish…

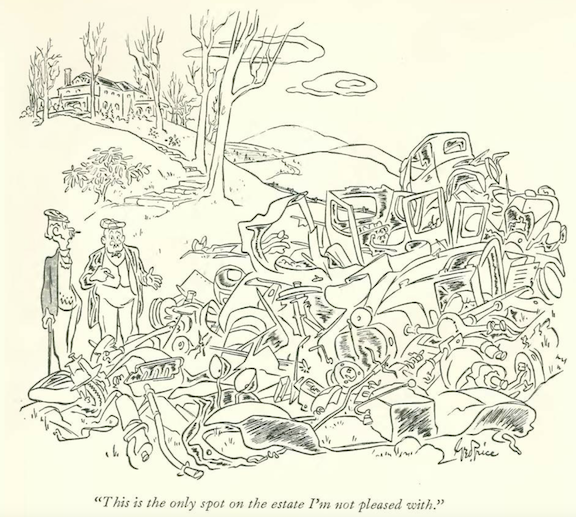

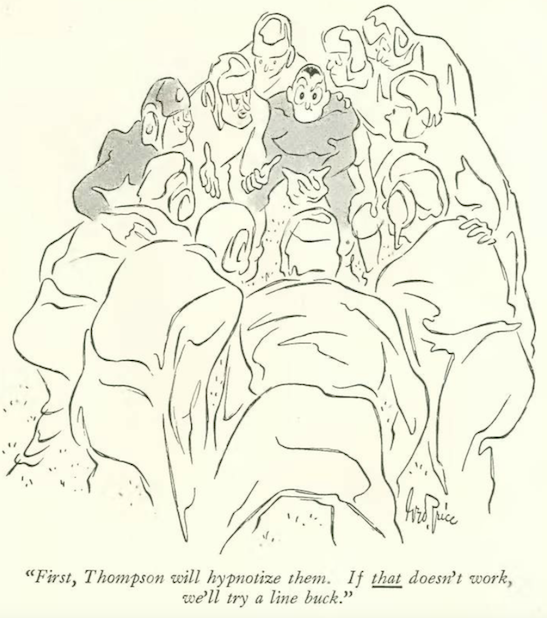

…George Price came across a landscaping challenge…

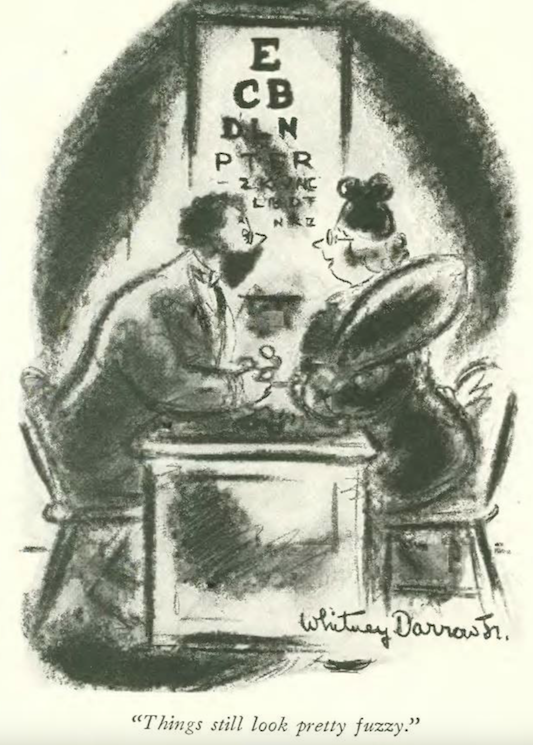

…Whitney Darrow Jr focused on a visit to the optometrist…

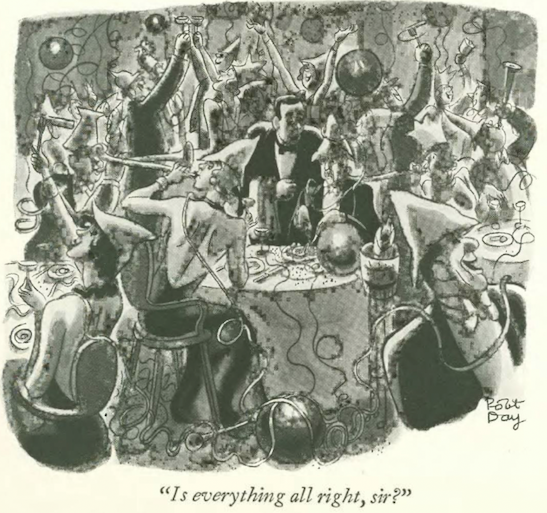

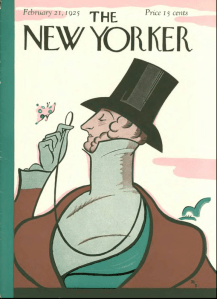

…Robert Day gave us a party pooper too pooped to party…

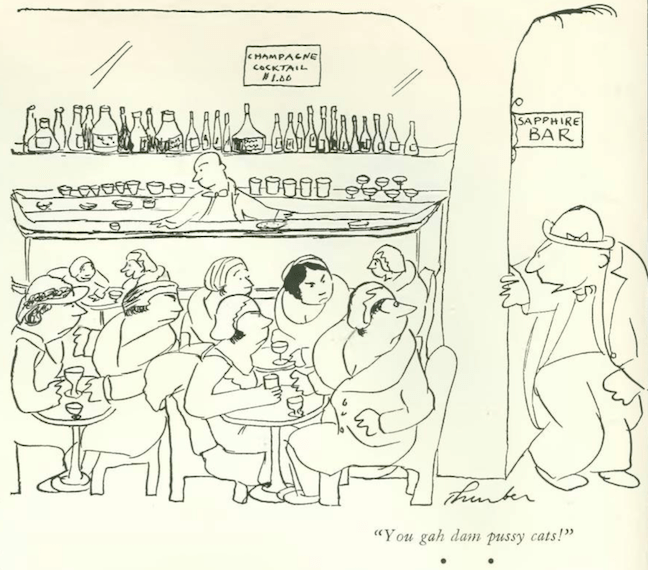

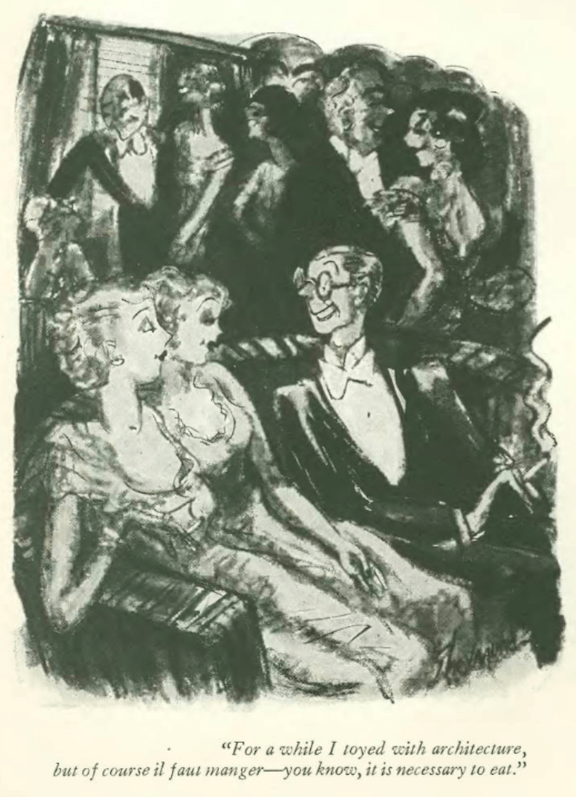

…and Peter Arno offered a glimpse into his active nightlife…

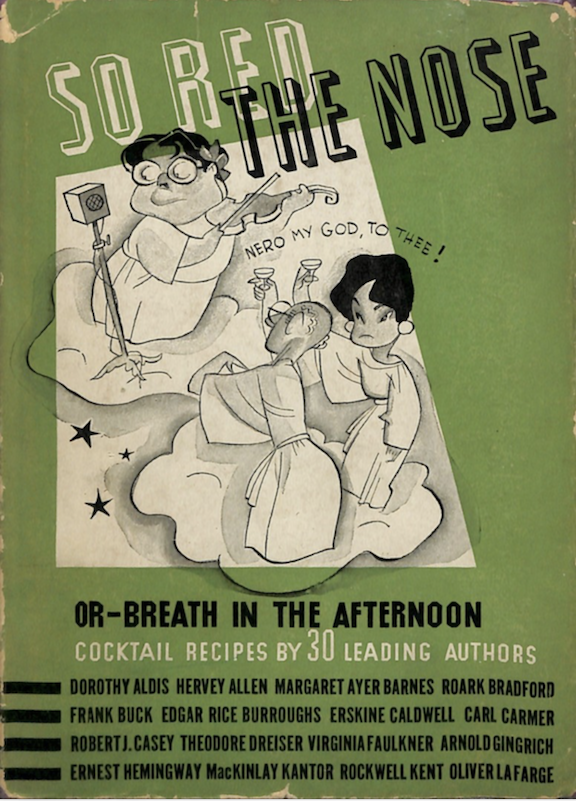

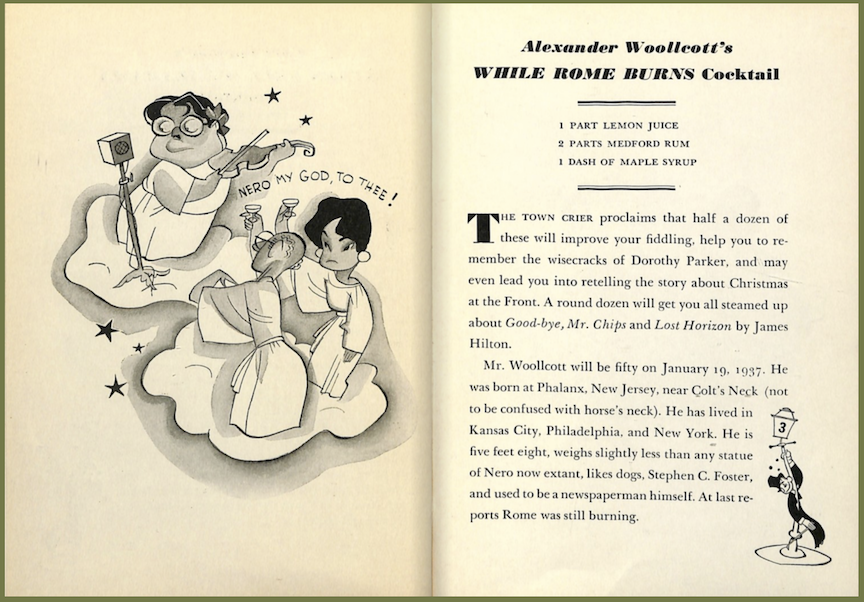

…before we go, I ran across this cocktail book, So Red the Nose, at Messy Nessy’s Cabinet of Curiosities…

…this particular tome featured an Alexander Woollcott recipe for a cocktail called “While Rome Burns”…

…you can flip through the entire book at this site…

Next Time: The Major’s Amateur Hour …