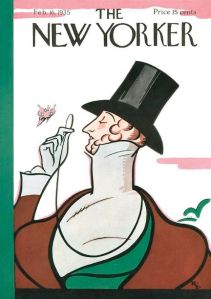

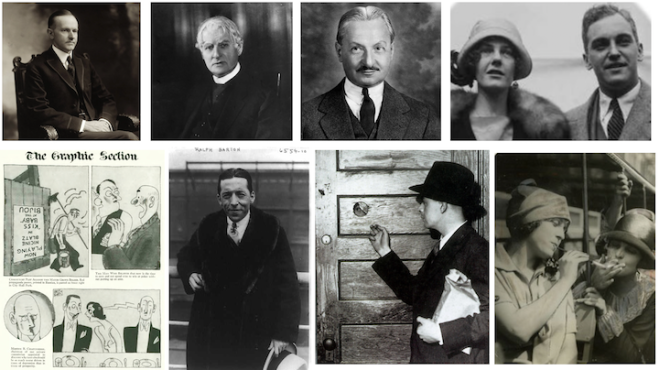

With this post (No. 413), we mark the tenth anniversary of The New Yorker. Since I began A New Yorker State of Mind in March 2015, I’ve attempted to give you at least a sense of what the magazine was like in those first years, as well as the historical events that often informed its editorial content as well as its famed cartoons. Those times also informed the advertisements; indeed, in some cases the ads give us a better idea of who was reading the magazine, as well as their changing tastes and buying power as we moved from the Roaring Twenties to the Depression, and from Prohibition into Repeal.

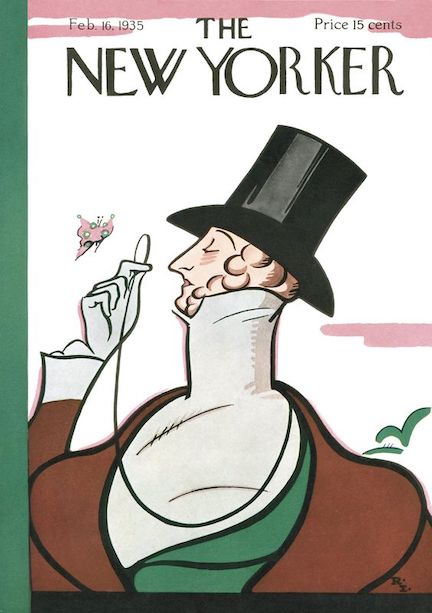

I have also chosen this time to go on hiatus, and hopefully resume this blog when The New Yorker celebrates its centennial next February (this site will remain active and available, and I will continue to monitor comments and messages). Let us hope that the editors use the original Rea Irvin cover for that occasion, and restore his masthead above “The Talk of the Town” section. Perhaps some enterprising soul could start a petition.

Moving on to the tenth anniversary issue, we find E.B. White recalling the world of The New Yorker’s first days. Given the massive economic and societal shifts that occurred from 1925 to 1935, those first days seemed distant to White, who felt old, “not in years but events.”

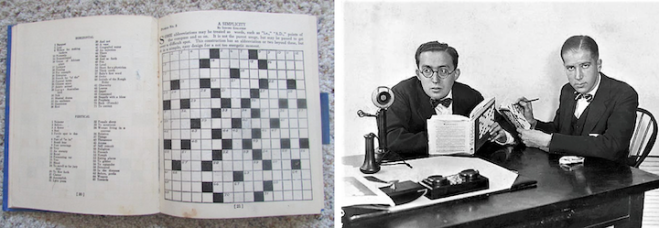

White also noted a new craze that had originated around the same time as the birth of The New Yorker…

White concluded with these parting words, tinged with world-weariness, writing “More seems likely to happen.” One wonders if he imagined The New Yorker at 100, which in our day is just around the corner. Like White, many us have grown weary of this angry world, where indeed more seems likely to happen. Let us hope it is for the best.

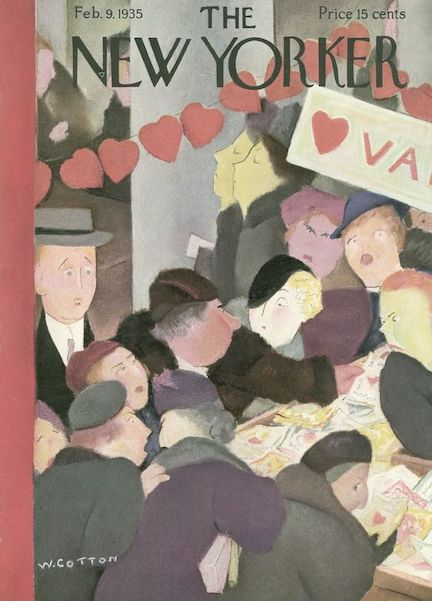

Now, some unfinished business. We need to look at the previous issue, Feb. 9, 1935, before we close out the decade.

We stay on the lighter side, joining critic John Mosher at the local cinema to appreciate Leslie Howard’s dashing performance in The Scarlet Pimpernel…

* * *

From Our Advertisers

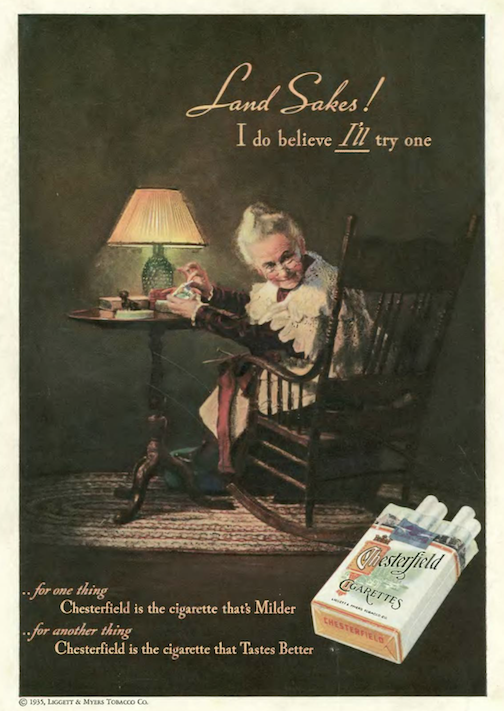

Cigarette manufacturers employed every angle from sex to health claims to move their product…not to be left out of any niche market, Chesterfield even went after the little old ladies…

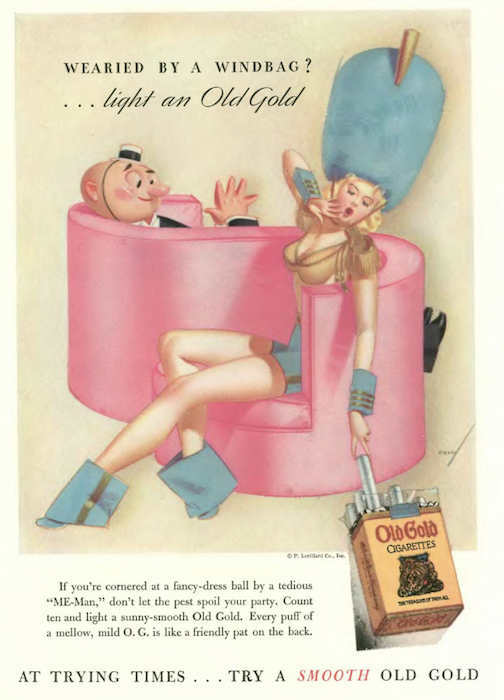

…by contrast, the makers of Old Gold cigarettes featured a clueless sugar daddy and his leggy mistress in a series of ads drawn by famed pin-up artist George Petty…

…Otto Soglow would do well with advertisers during his career, promoting everything from whiskey to Pepsi and Shredded Wheat to department stores…in this case Bloomingdale’s…after William Randolph Hearst’s King Features Syndicate wrested The Little King away from The New Yorker in September 1934, this was the only way you would see the harmless potentate in the magazine…

…another New Yorker artist earning some ad dollars on the side was Constantin Alajalov, here adding a stylish flair for Coty…

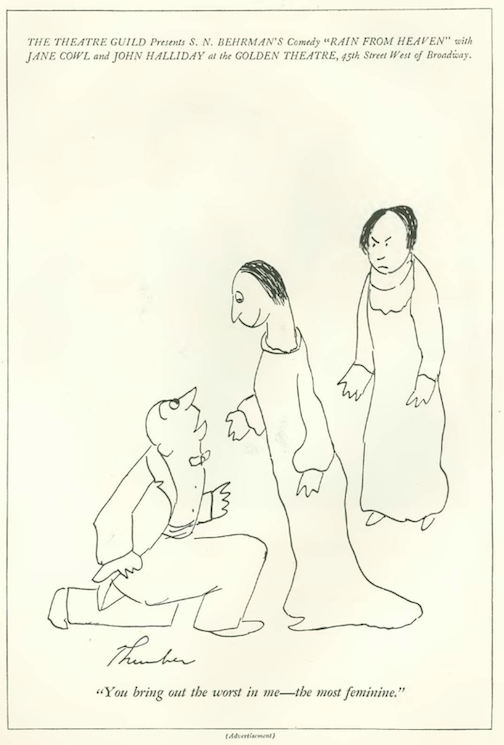

…and then there’s James Thurber, who continued to contribute his talents on behalf of the Theatre Guild…

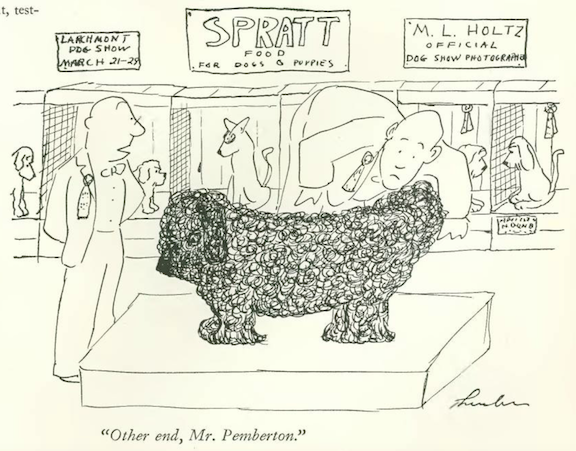

…and we move along to the Feb. 9 cartoons, with Thurber again…

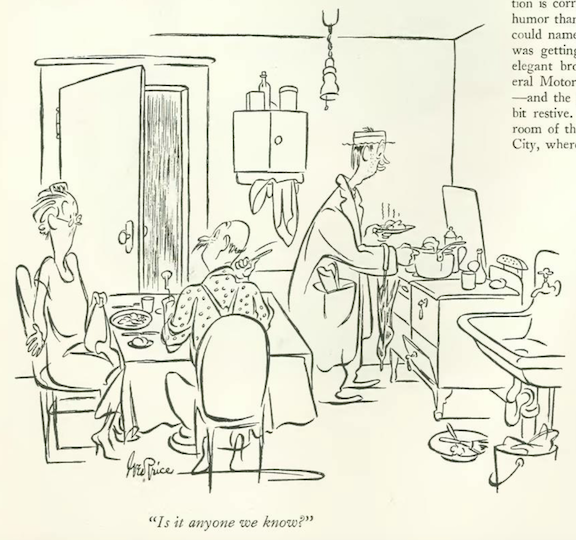

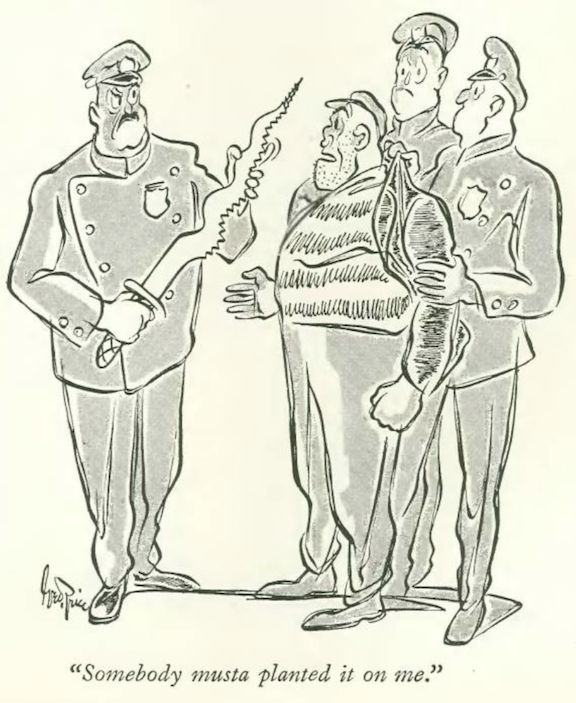

…the issue also featured two by George Price…

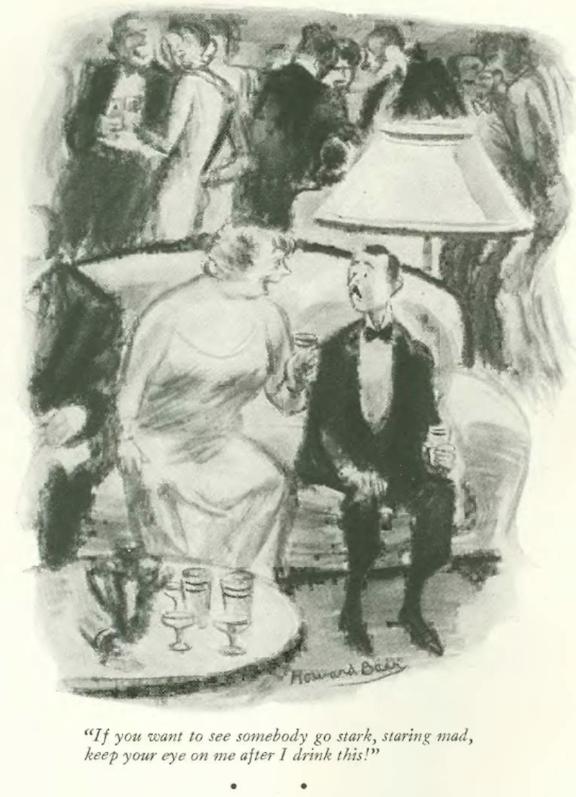

…and Howard Baer supplied some life to this little party…

…now let’s return to the Feb. 15, 1935 issue…

…where John Mosher was back at the cinema, this time enjoying the story of a “beautiful stenographer”…

* * *

More From Our Advertisers

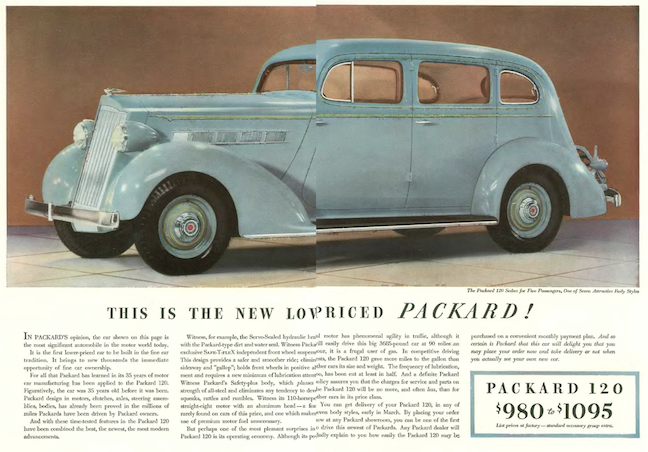

In its bid for survival during the Depression, the luxury brand Packard introduced its first car under $1000, the 120. Sales more than tripled in 1935 and doubled again in 1936…

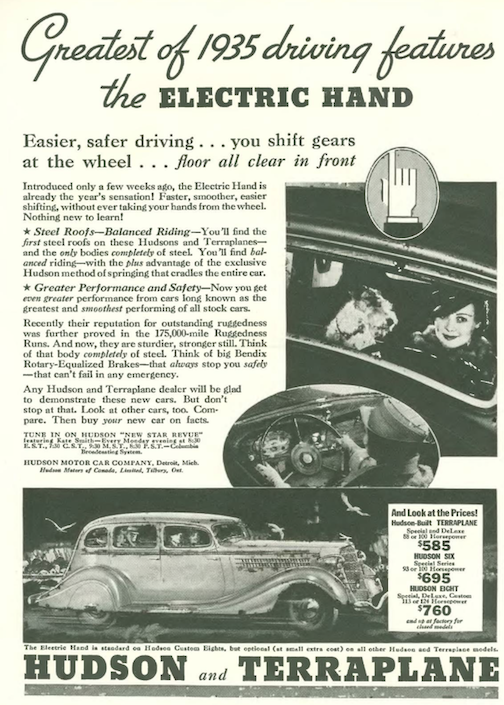

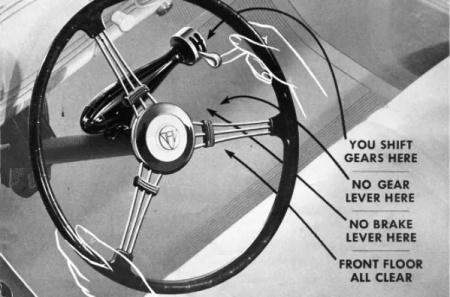

…meanwhile, Hudson was hanging in there with innovations such as the “Electric Hand”…it was not a true automatic transmission, but it did allow drivers to shift gears near the steering wheel…

…as demonstrated here…

…whatever you were driving, Goodyear claimed it would keep you the safest with their “Double Eagles”…

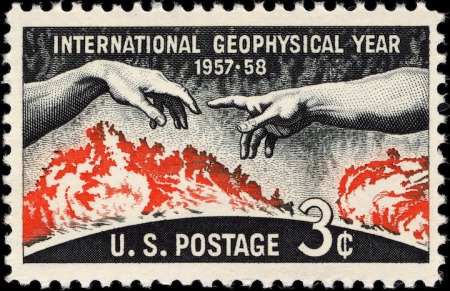

…I include this ad for Taylor Instruments because it features an illustration by Ervine Metzl, who would become known for his posters and postage stamp designs…

…Metzl’s design of a three-cent stamp commemorating the 1957–1958 International Geophysical Year…

…on to our cartoonists, we begin with this Deco-inspired artwork by an unidentified illustrator…

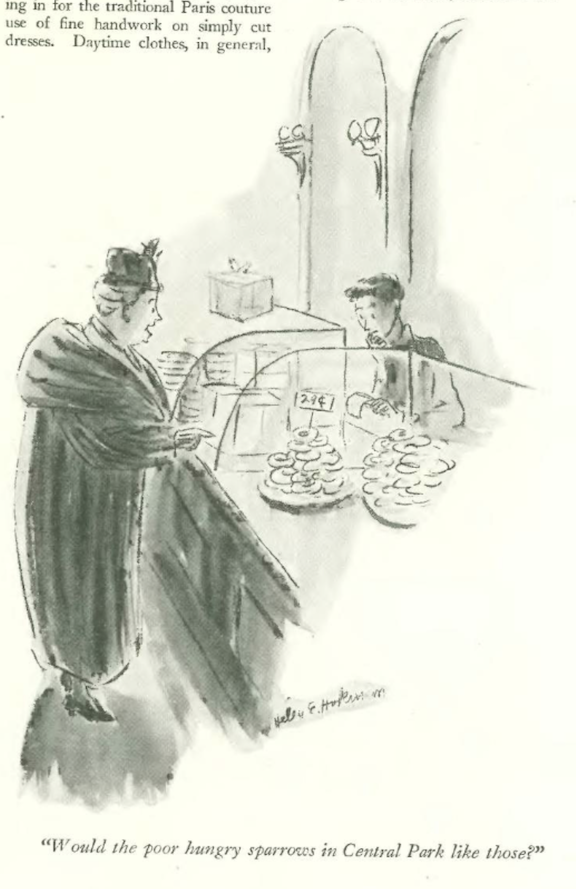

…one of Helen Hokinson’s “girls” was going about her daily rounds…

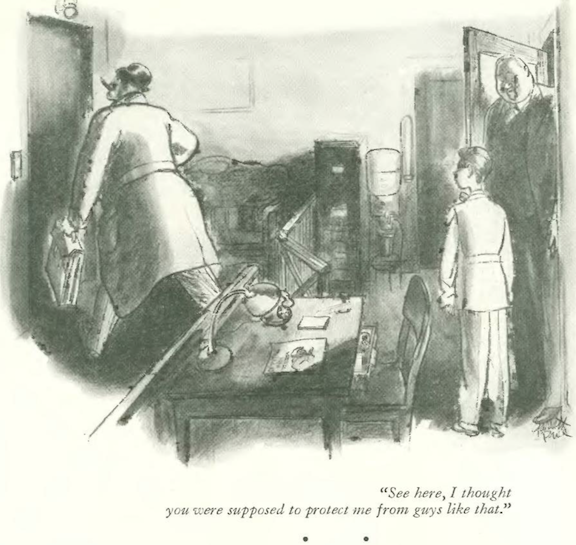

…Garrett Price gave us a gatekeeper not quite up to his task…

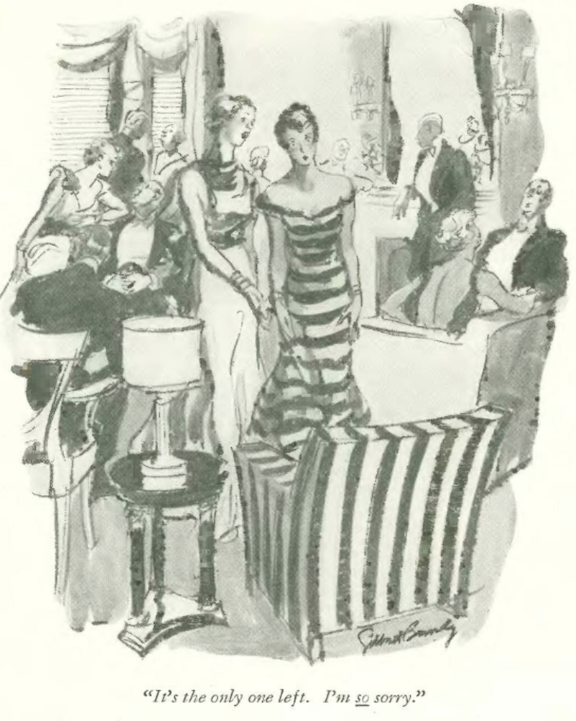

…Gilbert Bundy was seeing stripes rather than stars…

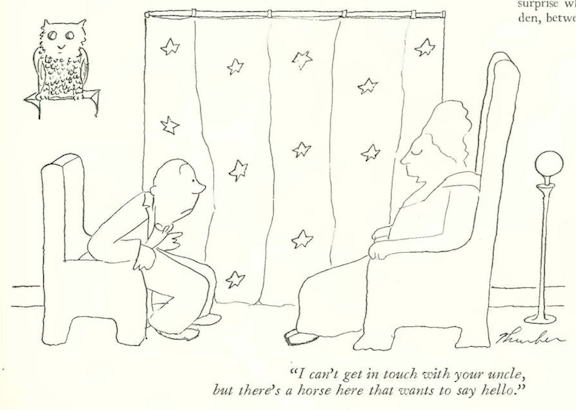

…while James Thurber’s medium was getting in touch with an equine spirit…

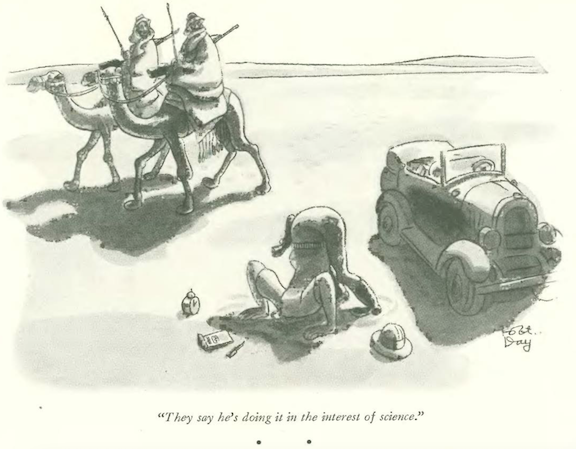

…scientific inquiry knew no bounds in Robert Day’s world….

…and in the world of Alain (aka Daniel Brustlein), old habits died hard…

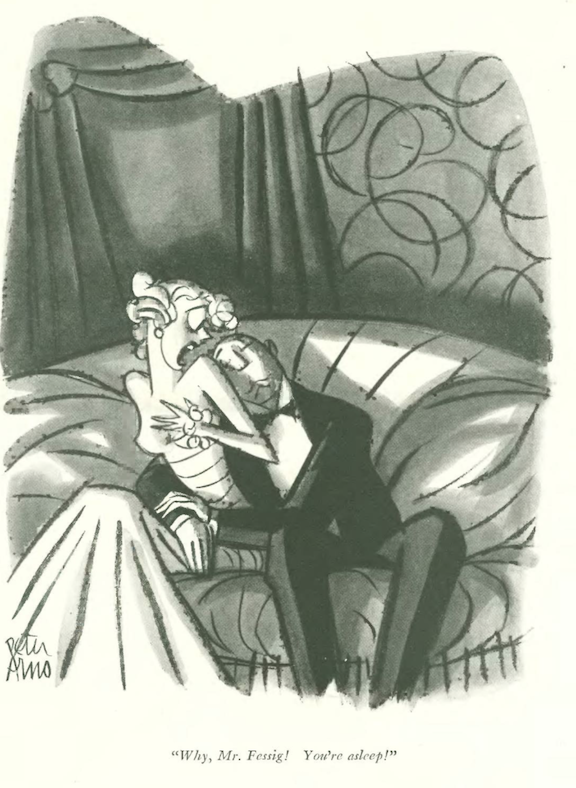

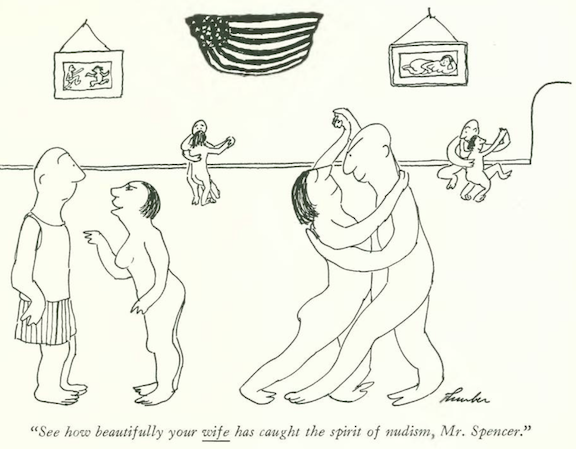

…and we close with Peter Arno, at his risqué best…

Thanks for reading The New Yorker State of Mind!