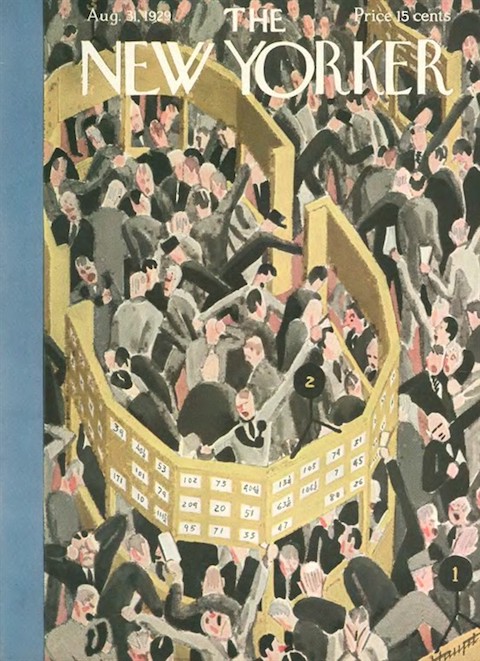

Avery Hopwood’s 1919 Broadway hit, The Gold Diggers, was among cultural events of the late teens that signaled the dawn of new age; namely, the Jazz Age.

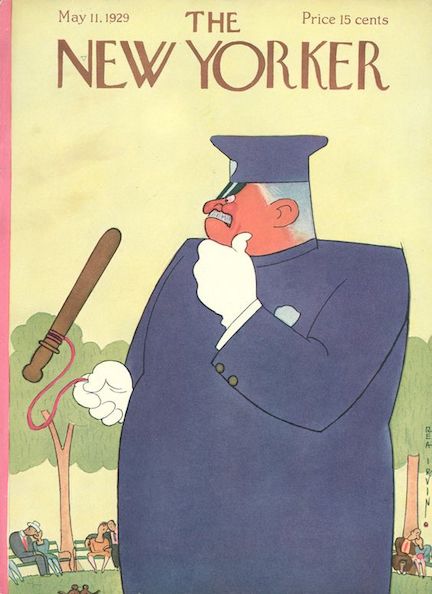

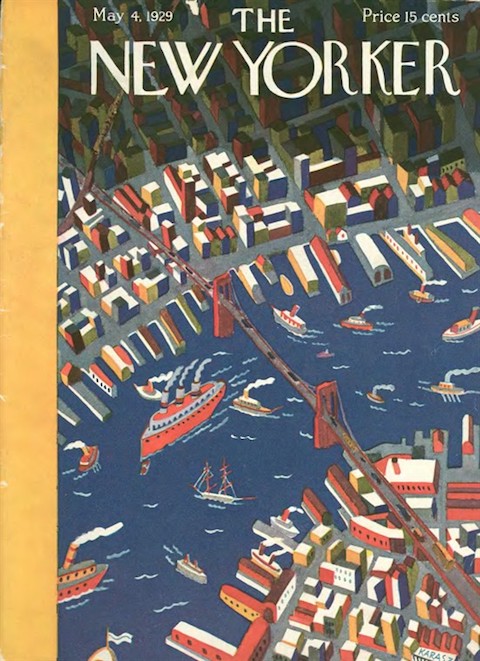

So it seems appropriate that the play, when adapted to the screen in 1929 as a Technicolor talkie, would also signal the end of that age. As the New Yorker’s film critic John Mosher observed in his review of The Gold Diggers of Broadway, the themes that seemed new and daring a decade earlier had been played out, the “general humors” of the picture having “become very familiar”…

The film featured Nancy Welford, Winnie Lightner and Ann Pennington as three chorus girls who try to entice a wealthy backer to invest money in their struggling Broadway show. The film was a big hit, and it made a star of Winnie Lightner (1899-1971), who played the boldest “Gold Digger” of the trio.

Lightner wasn’t the only actor to steal the show. The film also proved a winner for crooner Nick Lucas (1897-1982), who performed two hit songs written for the movie — “Painting the Clouds with Sunshine” and “Tiptoe through the Tulips.” Yes, that second song was the very same tune Tiny Tim rode to fame nearly 40 years later.

The Gold Diggers of Broadway was a “pre-code” film, that is, a film made during a brief period of the early sound era (roughly 1929 through mid-1934) when censorship codes were not enforced and many films openly depicted themes ranging from promiscuity and prostitution to amoral acts of violence.

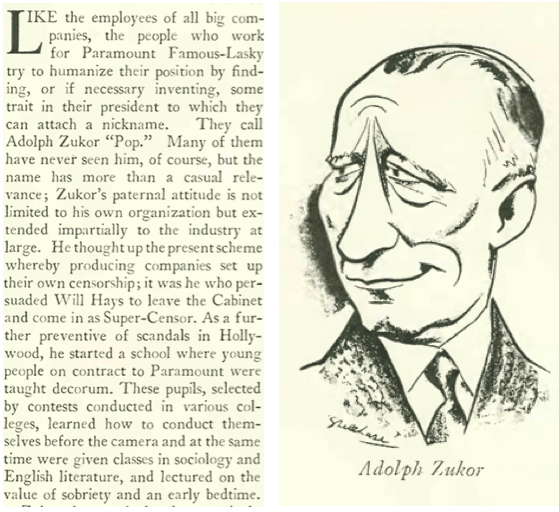

Those unenforced codes had their origins in the early 1920s. In response to outcries from preachers and politicians alike over the immortality of Hollywood (both on- and off-screen), the president of Paramount Pictures, Adolph Zukor — fearing that cries for censorship would cut into his profits — called a February 1921 meeting of his studio rivals at Delmonico’s restaurant on 5th Avenue. At the meeting Zukor (1873-1976) distributed a set of 14 rules that would guide every Paramount production (Zukor’s studio at that time was actually known as Famous Players-Lasky). The rules covered everything from “improper sex attraction” to “unnecessary depictions of bloodshed.”

It was also Zukor’s idea to appoint the former U.S. Postmaster General, Will Hays, as President of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America. It would be Hays’ job to enforce the code and generally “clean up” Hollywood. However, until mid-1934 both Hays and the code served mostly as publicity ploys to keep the preachers and politicians off the backs of studio execs.

Zukor was profiled by Niven Busch, Jr. in the Sept. 7 issue (with portrait by George Shellhase). In his opening paragraph, Busch commented on “Pop” Zukor’s efforts to stave off the censors:

* * *

Delmonico’s Redux

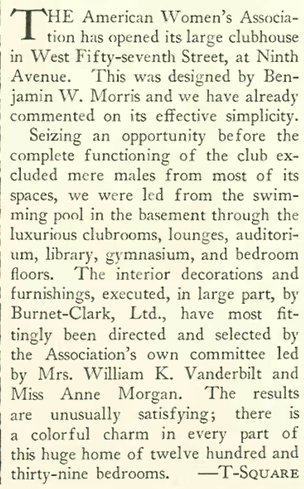

The famed Delmonico’s restaurant that provided the setting for Adolph Zukor’s “14 rules” meeting in 1921 closed its doors in 1923, a victim of Prohibition (more people dined at home, where they could still drink). Writing in the Sept. 7 “Talk of the Town,” Bernard A. Bergman described plans for the long-awaited opening of a new Delmonico’s in a skyscraper bearing the same name…

A former Delmonico’s chef, Nicholas Sabatini, hoped to bring back some of old waiters and cooks from the restaurant’s glory days, but it seemed most were far too long in the tooth. It is unclear if he ever got his dream off the ground, or if the grill room was able to crank out fare comparable to that of the old Delmonico’s. Probably not…

* * *

Relax. You’re in Omaha

E.B. White’s “Notes and Comment” entry in the Sept. 7 “Talk of the Town” described travel on the Union Pacific’s Overland Limited, and the “mystic dividing line” that separated laid-back Westerners from buttoned-up Easterners:

* * *

Write What You Know

The Wisconsin-born Marion Clinch Calkins (1895 – 1968) often wrote humorous rhymes for The New Yorker under the pen name Majollica Wattles. While many writers reveled in the party atmosphere of the Roaring Twenties, Calkins worked as a vocational counselor and social worker at Lillian Wald’s Henry Street Settlement. This experience doubtless led her to more serious writing after the 1929 market crash — her critically acclaimed book, Some Folks Won’t Work (1930), is considered a seminal document on the Great Depression.

But in September 1929, Calkins was still in a humorous vein, and published this satirical piece on the role of an ideal housewife in the Sept. 7 issue. Excerpts:

* * *

Information Please

The New Yorker’s art critic Murdock Pemberton did not suffer fools gladly, and whenever the local museums seemed less than up to snuff, he was there to provide some correctional advice…

* * *

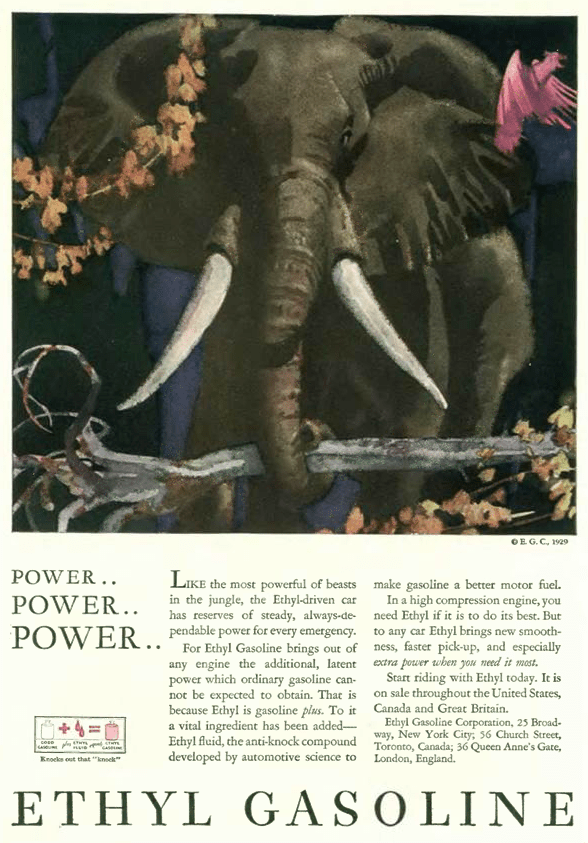

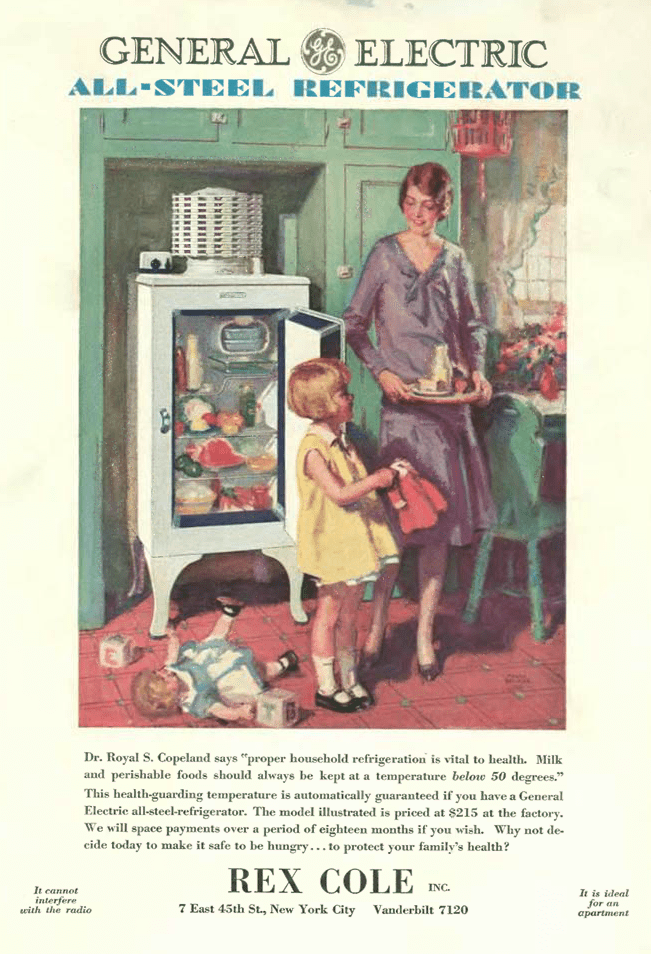

From Our Advertisers

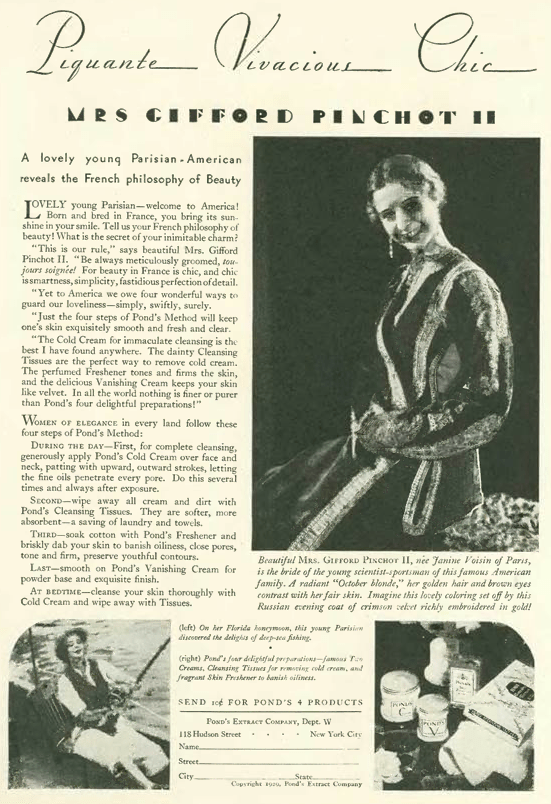

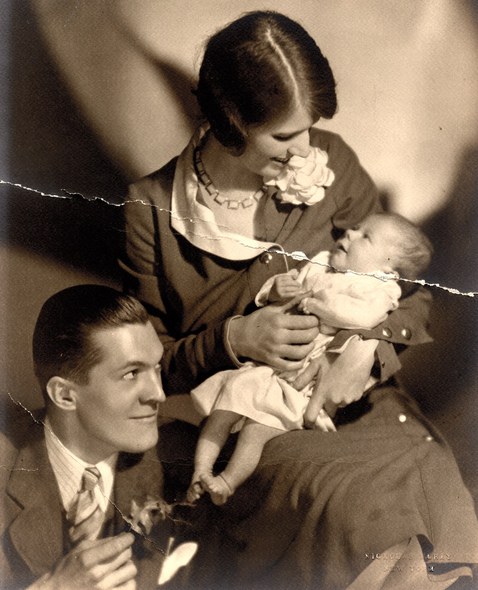

Despite the advances made by women in the 1920s, they still lived under a patriarchy, especially when it came to the patrician classes. And so the young bride of Gifford Pinchot II was identified only as a “Mrs.” in the headline for this Pond’s cold cream ad…

…Mrs. Gifford Pinchot II was actually Janine Voisin (1910-2010). She must have had more than a healthy complexion, as she lived 100 years…

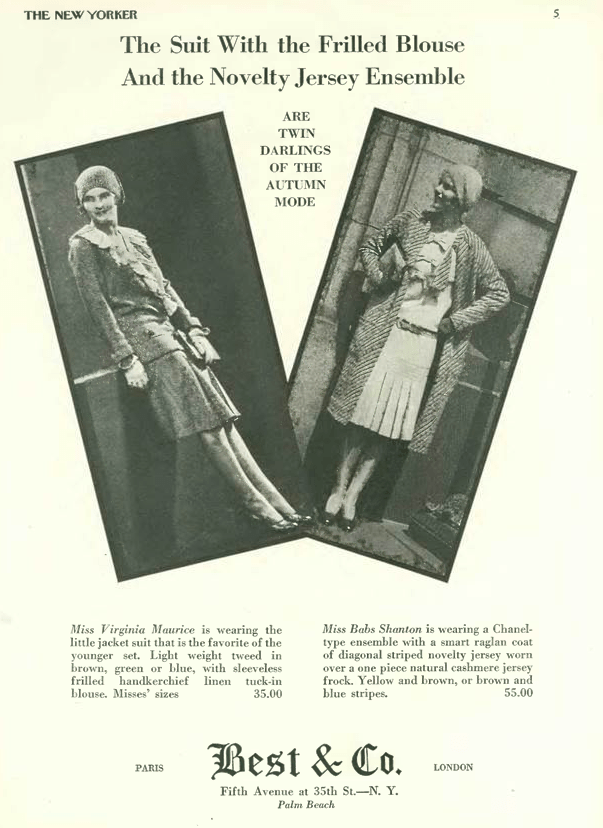

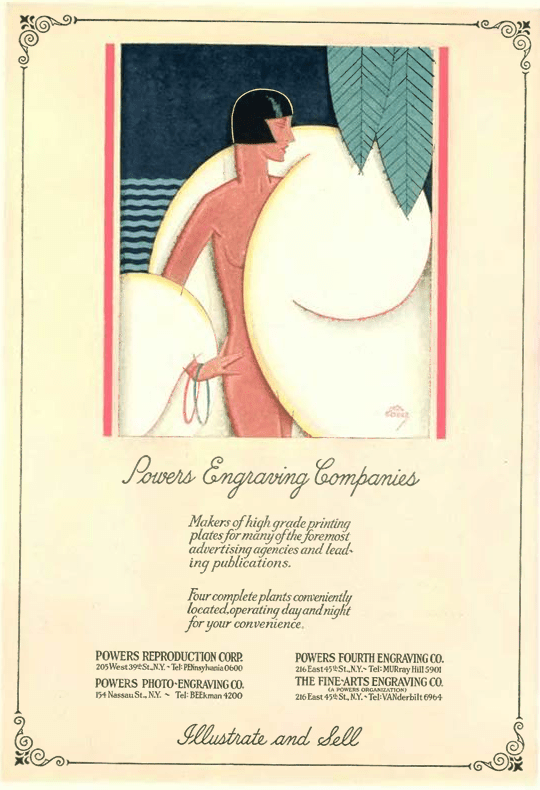

Another woman known for her beauty in the 1920s was the model Marion Morehouse (who was married to poet E.E. Cummings from 1934 until his death in 1962). Considered by some to be the first “supermodel,” I include an image of Morehouse below (right) to demonstrate how artists exaggerated the female form in fashion ads of the day…

…the body wasn’t the only thing subject to exaggeration, or hyperbole, as this ad from Harper’s Bazar attested in defining the exclusivity of its readership…

…the New York Sun also appealed to social mores in an attempt to sell more newspapers…

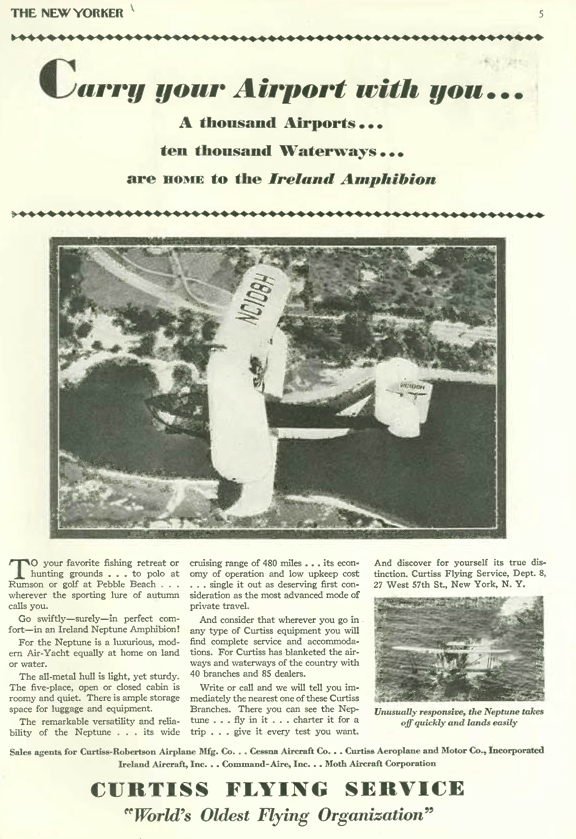

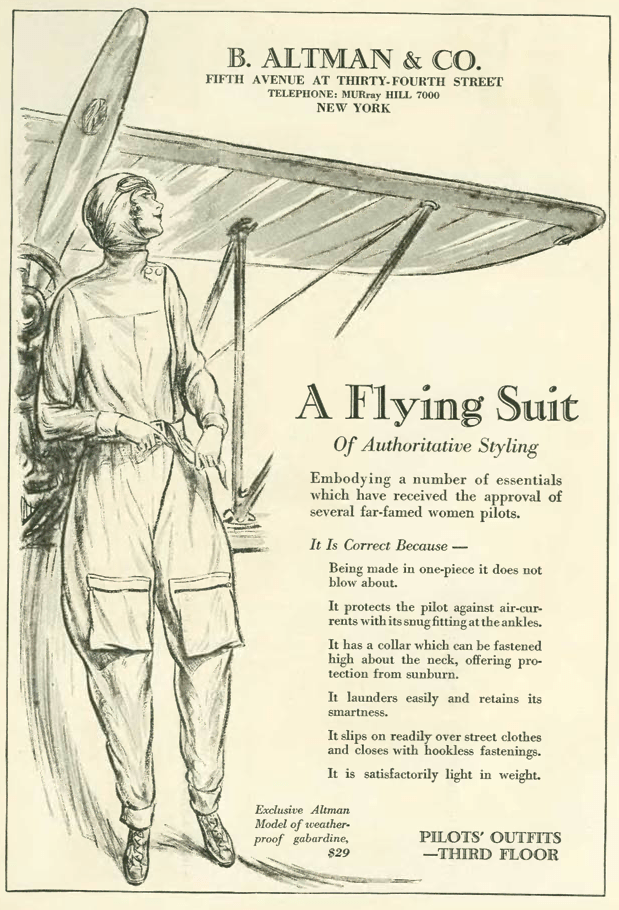

…the Curtiss Robin Flying Service touted their latest achievement — the St. Louis Robin being refueled during its flight to a new world’s endurance record of 420 hours — greatly surpassing the record of 150 hours set by the Army’s “Question Mark” airplane at the beginning of 1929…

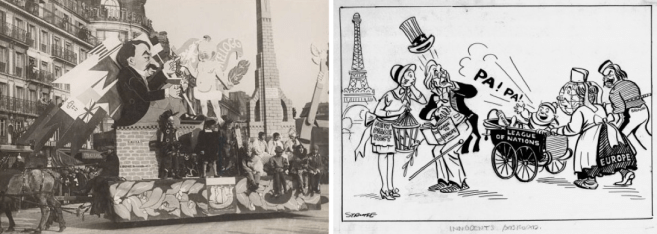

…our cartoonists from the Sept. 7 issue include Gluyas Williams, who had some fun at the expense of Alice Foote MacDougall, who was the “Starbucks” of her day, at least in New York…

…MacDougall turned her coffee business into a restaurant empire in the 1920s. She opened several restaurants in Manhattan, all decorated in a signature style meant to evoke European cafés…

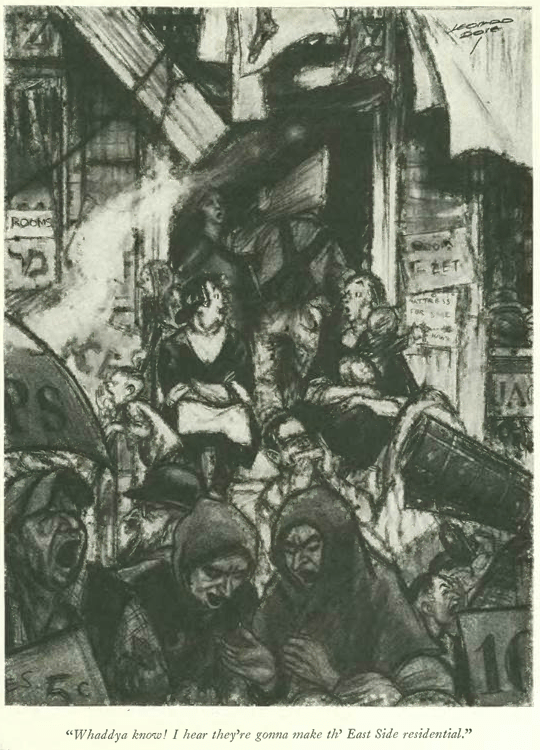

…other cartoons included this commentary on public advertising by Leonard Dove…

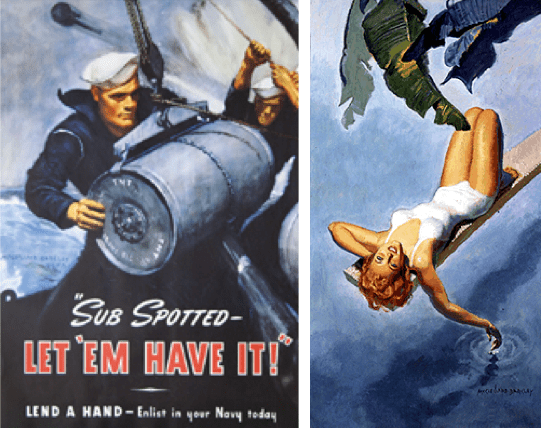

…Peter Arno’s unique take on the seafaring life…

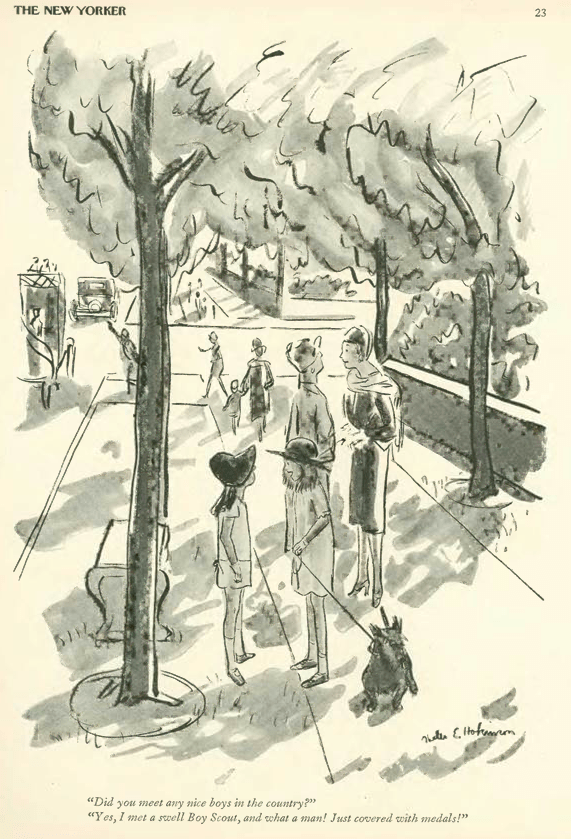

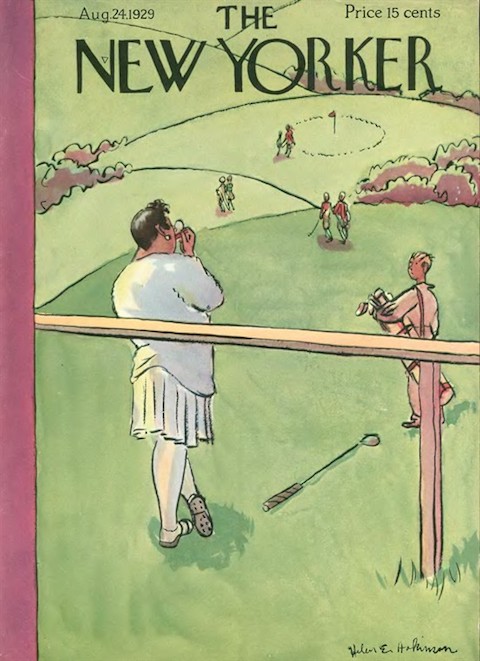

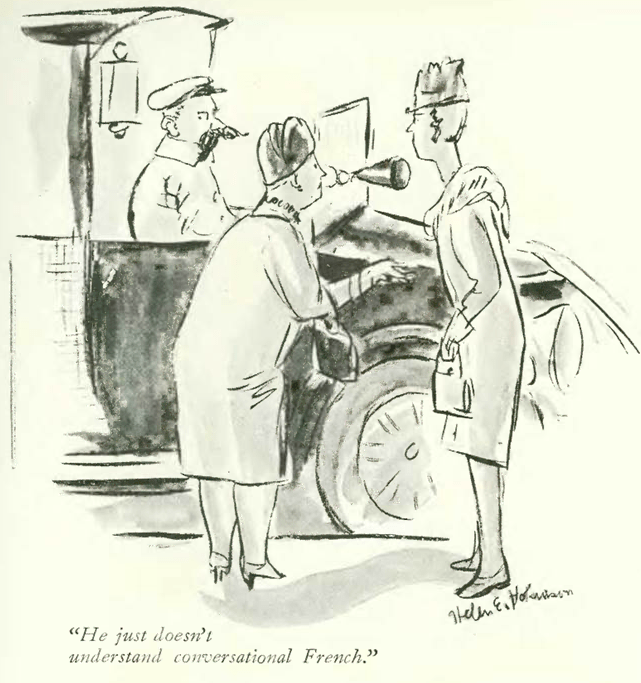

…Helen Hokinson eavesdropped on some tween talk…

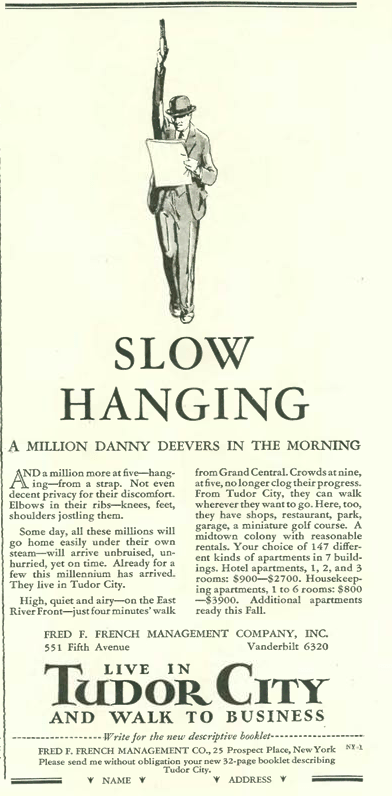

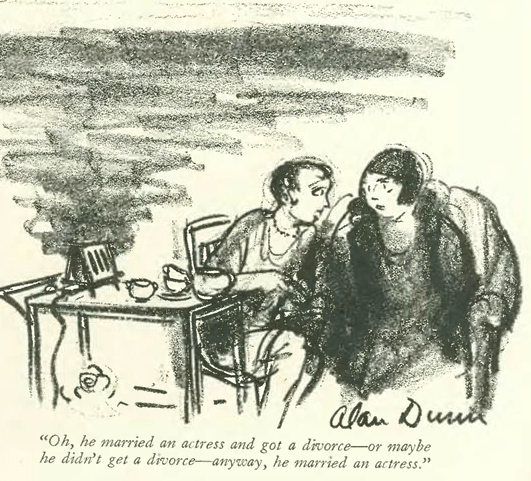

…and Alan Dunn gave us some perspective on the fast pace of city life…

Next Time: From Stage to Screen…