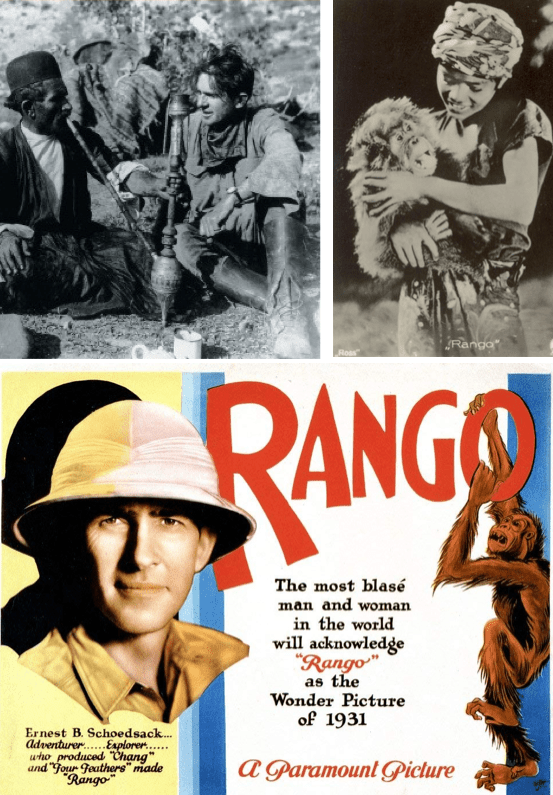

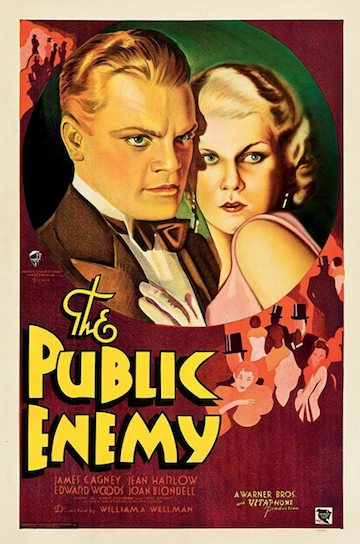

In the previous issue, New Yorker film critic John Mosher examined the morals of pre-code, “underworld films” such as Edward G. Robinson’s Little Caesar. Mosher didn’t seem all that impressed with these new gangster films, that is, until James Cagney lent his talents to The Public Enemy.

Despite its violence (by yesterday’s standards), Mosher believed that even the preachers and various women’s committees who decried the sex and violence in pre-code movies would have little to gripe about with The Public Enemy, since it clearly depicted the wages of the sins of Tom Powers, a bootlegger on the rise portrayed by Cagney.

* * *

Flag of a Father

Speaking of morality, no voice was louder, or carried farther, than that of Charles Edward Coughlin (1891-1979), known familiarly as “Father Coughlin,” an enormously popular radio priest who had an estimated following of 30 million listeners in the 1930s. E.B White took notice of this phenomenon, and also the Father’s stand against “internationalism,” which in a few years would morph into a virulent nationalism and anti-semitism that would find the Father finding common cause with Hitler and Mussolini. Yes, those guys. But for now, we are still in 1931…

* * *

Paradise Lost

Far up the Henry Hudson Parkway, just before you cross Spuyten Duyvil Creek (Harlem River) into Younkers, is a park with a history that goes back to a Lenape tribe that occupied the site prior to European settlement. Inwood Hill Park is where, legend has it, Peter Minuit purchased Manhattan from the Lenape on behalf of the Dutch West India Company.

Inwood served as a location for a fort during the Revolutionary War, and was dotted with working farms including one owned by the Jan Dyckman family, established in 1661. In the 19th century a number of wealthy New Yorkers built country retreats around Inwood, which became a park in 1926. Squatters continued to live in abandoned estates around the edge of the park until Robert Moses came along in the 1930s and cleared them out. E.B. White, in “The Talk of the Town,” takes it from there.

The Dyckman farmhouse fell into disrepair by the late 1800s, seen here in 1892…

…but it was restored in 1916, and still stands today at Broadway and 204th Street…

White wondered how Inwood would appear in ten years, now that parks workers were paving over the old Indian trails and landmarks like the Libby Castle were being torn down to make way for John D. Rockefeller’s Cloisters and Fort Tryon Park.

Built around 1855, Libby Castle was home to several New York bigwigs including William “Boss” Tweed of Tammany Hall fame. It was bulldozed in 1930-31 to make way for John D. Rockefeller’s Cloisters.

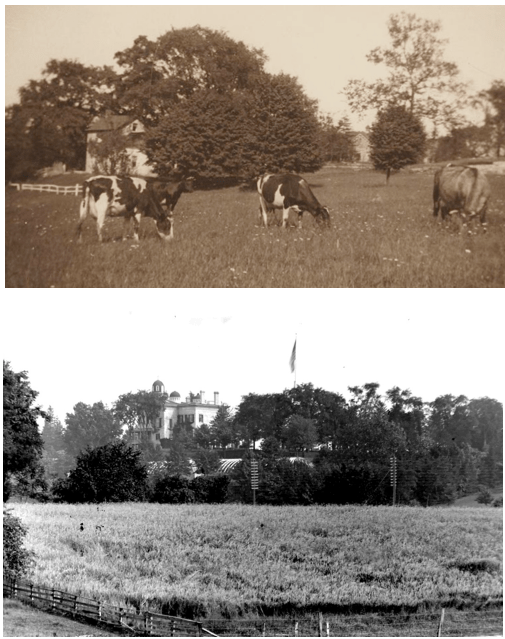

Inwood contained the last remaining farms in Manhattan — below are cows grazing in 1900 at site today now occupied by Isham Park, located on the southeast edge of Inwood Park. The next photo, from 1895, identifies “the last field of grain on Manhattan Island.” In the background is the Seaman Mansion at Broadway and 216th Street…

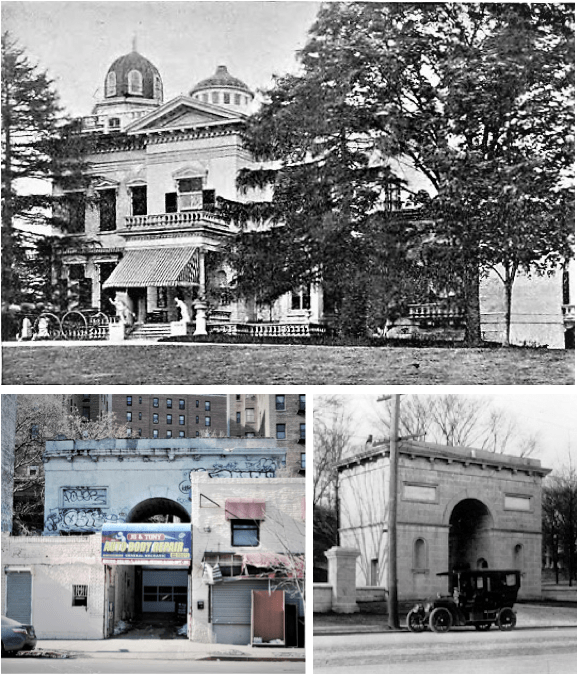

Below is a closer view of Seaman Mansion, a white marble, 30-room pile built around 1852. When this photo was taken in 1895, it had just become the new home of a riding club. Entry to the mansion was through a gatehouse, pictured below at right. The mansion was demolished in 1938 as the area around it filled up with cheap commercial buildings. Only the gatehouse remains, crumbling behind an auto body shop as seen in this 2015 image (bottom left):

And here’s the latest view from Google maps. Note how the business is now renamed (ironically, yes) after the crumbling arch behind it…

But let’s be fair; there is still much beauty to be had at Inwood. Check out this lovely fall panorama…

* * *

Rub-a-Dub-Dub

One of the great British modernists of the 20th century — perhaps best known for his 1915 novel, The Good Soldier — Ford Madox Ford (1873 – 1939) led a complicated personal life filled with indecision and anxiety. It makes sense that a man, in search of some order in his life, imposed a strict routine on bath time (and also found time for a bit of humor). Here is an excerpt from Ford’s submission to the May 2, 1931 New Yorker:

* * *

Tete-a-tete

Humorist and poet Arthur Guiterman was a regular contributor of comic verse to The New Yorker from its first days in 1925 until his death in 1943. In the April 18, 1931 issue, he dashed off this poem to Ralph Pulitzer, imploring him to give his family’s namesake Plaza fountain, and its “goddess of abundance,” a much-needed scrubbing…

No doubt to Guiterman’s delight, he received a reply in the May 3 issue, also in verse, from Ralph Pulitzer himself…

Well, Pulitizer was good for his word, and the fountain was cleaned and restored in 1933. There have been other restorations in 1971, 1985-90. Here is how it looks today:

* * *

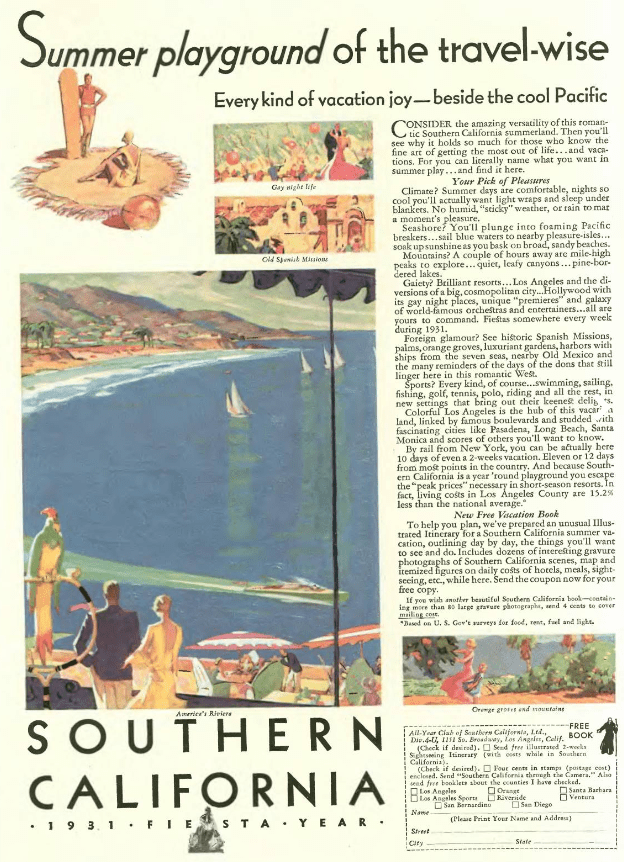

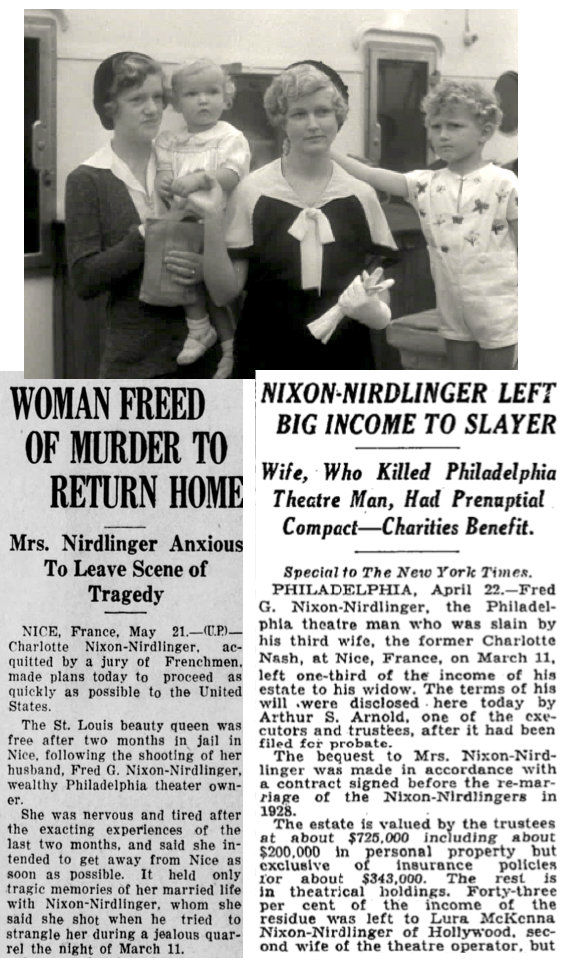

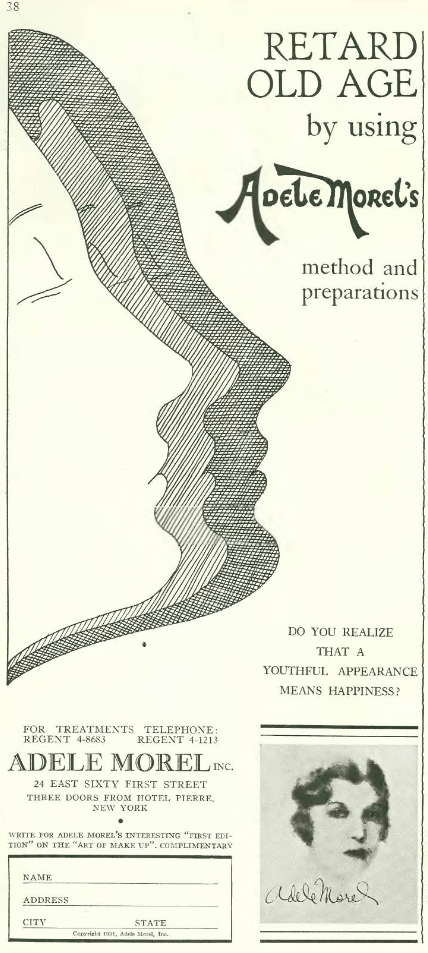

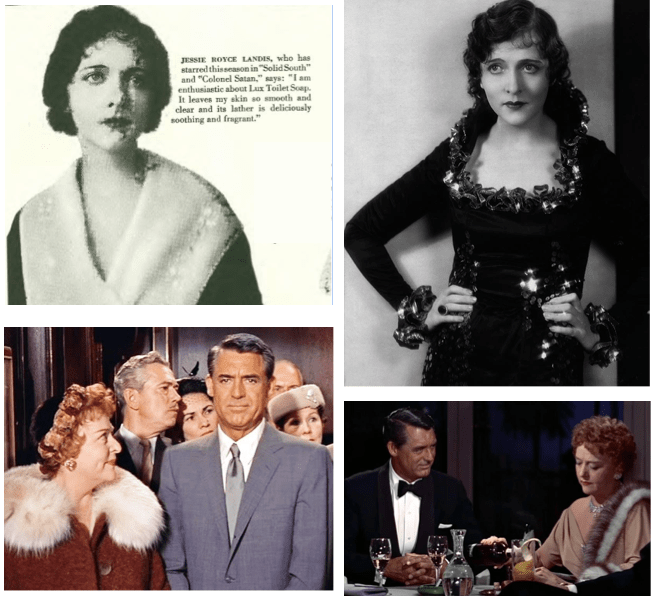

From Our Advertisers

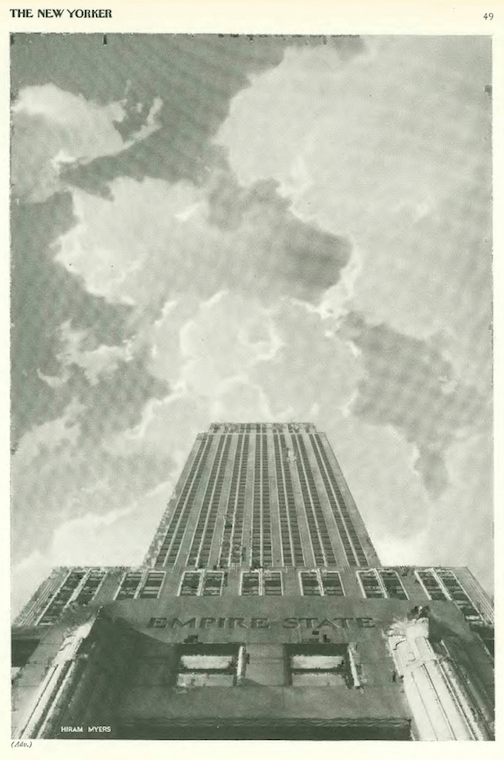

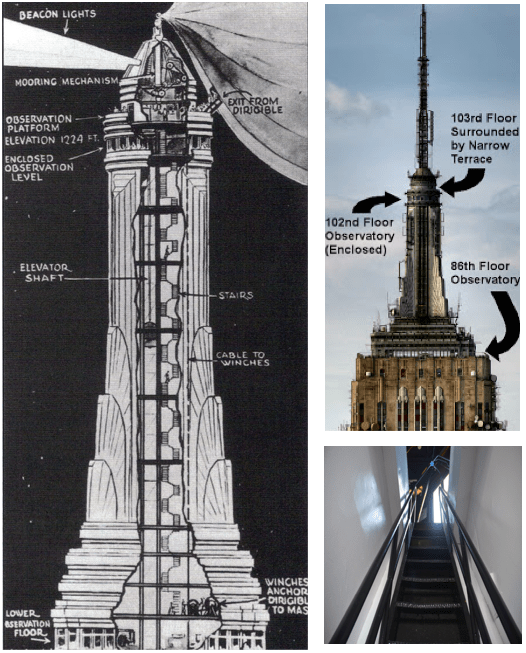

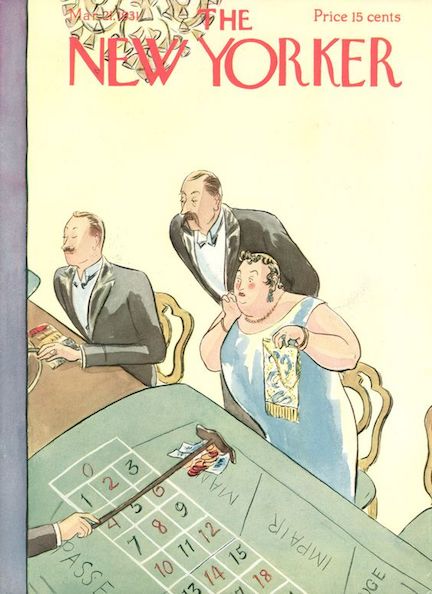

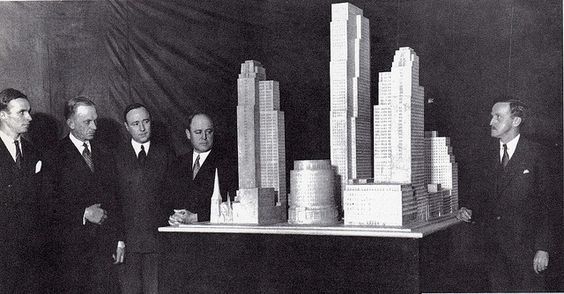

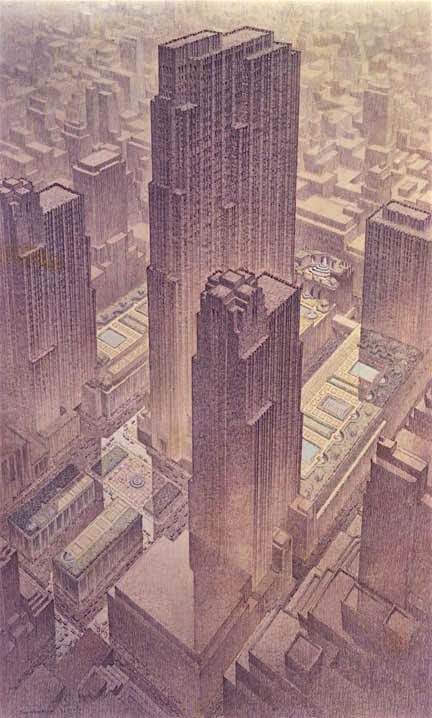

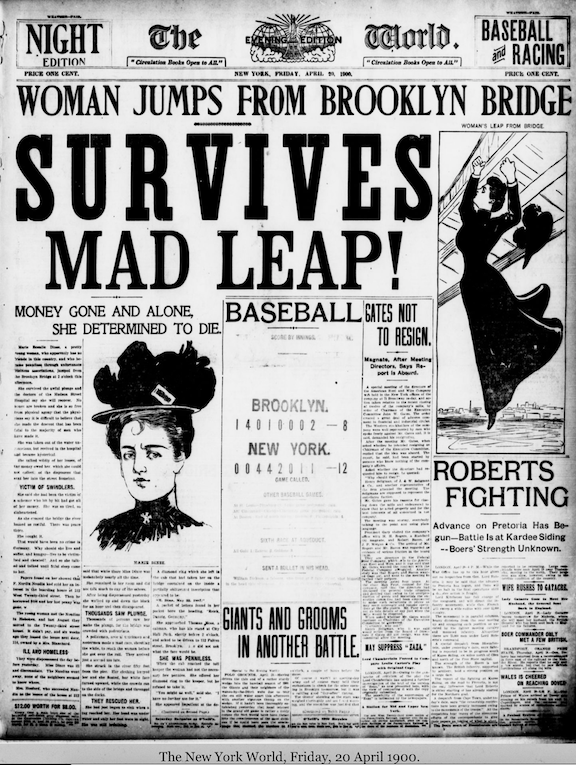

The Empire State Building officially opened its doors for business, and to mark the occasion the building’s promoters ran this full page ad that said it all: we are the biggest. Period.

In the back pages another ad touted the amazing views one could afford from the highest spot in the city…note the couple in formal wear having a leisurely smoke as they gaze over the metropolis, their view unobstructed by fencing later added in 1947 to prevent suicidal leaps…

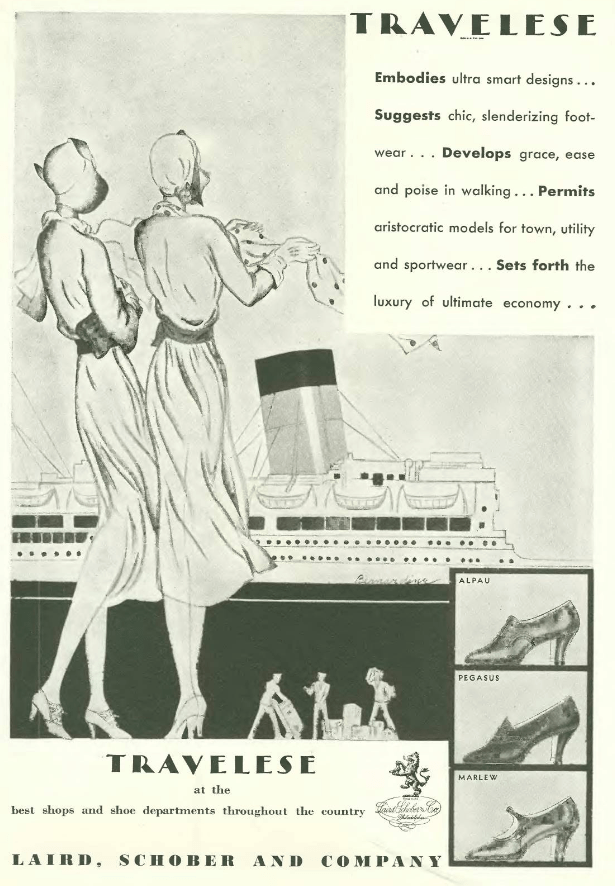

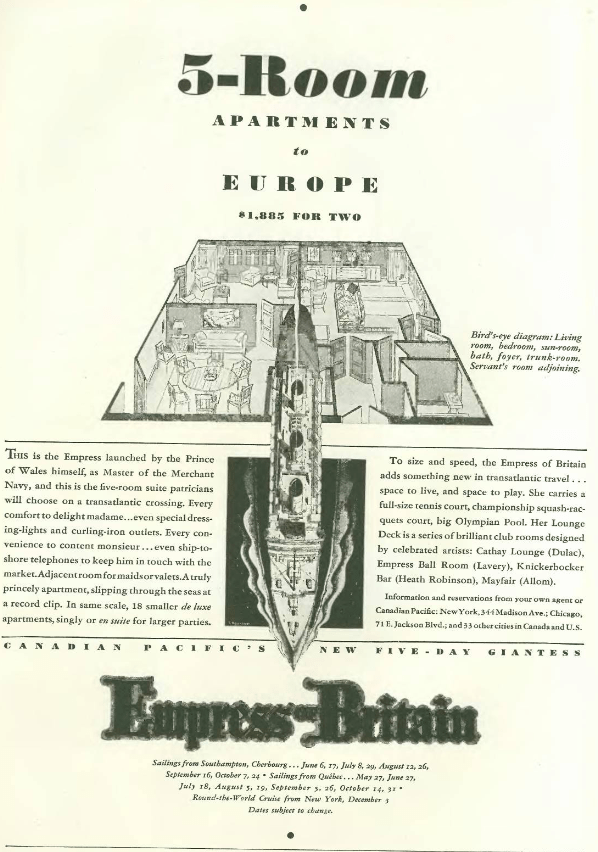

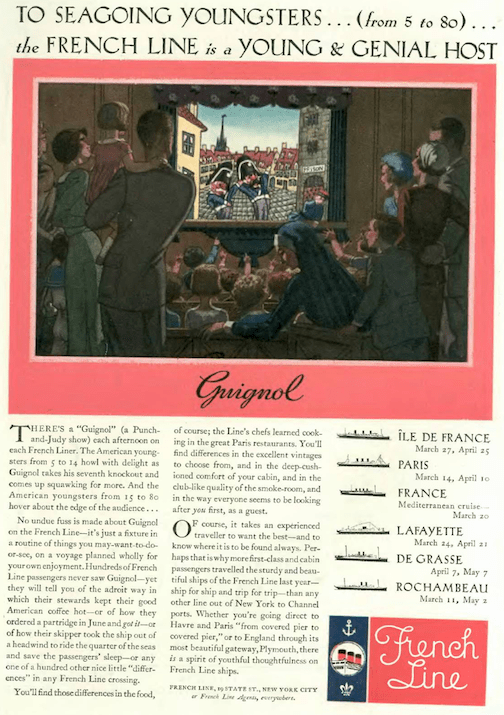

…speaking of large things, folks in the 19th and 20th centuries marveled at the gigantic scale of the man-made world—the Empire State Building, the Hindenburg, Hoover Dam, and ships with names like Titanic and Leviathan, the latter seen below in this ad from the United States Line…

…one of the largest and most popular ocean liners of the 1920s, the U.S.S. Leviathan was actually built in 1914 for Germany’s Hamburg-American Line and christened the Vaterland. During World War I the American government seized the ship while it was docked in Hoboken, New Jersey and used it to transport troops. After the war, it was refurbished and re-christened Leviathan. It was scrapped in 1938…

…if you took the boat to Paris, you probably had enough money to make an overseas call back home…it would set you back almost $34 for three minutes of static-filled chat, about $550 in today’s dollars…

…and despite the Depression, the thrills of the modern world still abounded, such as GE’s “all-steel” electric refrigerator so artfully depicted in this ad…

…and check out these Chryslers, looking absolutely luxurious…

…as do these Dodge boats, their polished wooden hulls gliding effortlessly through placid waters…

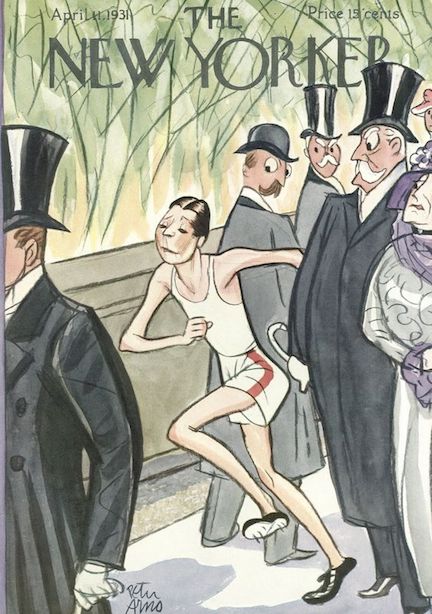

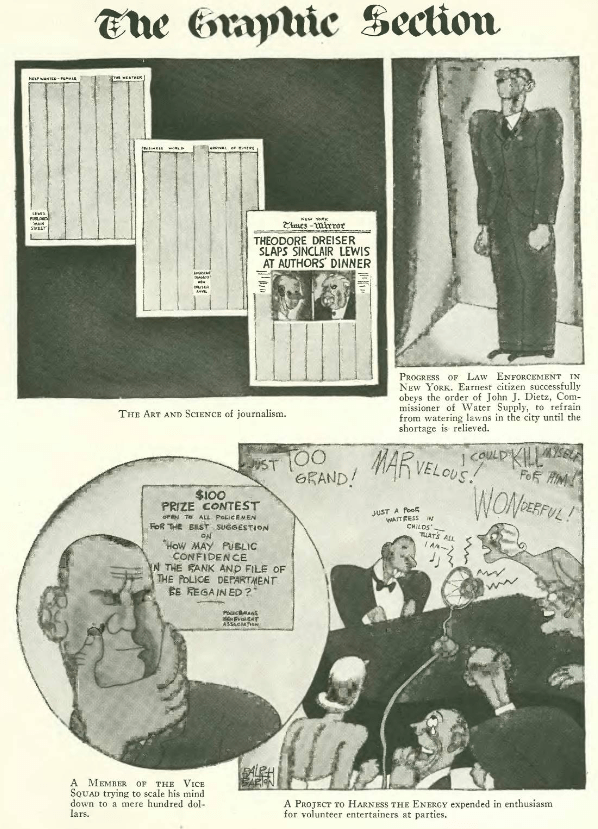

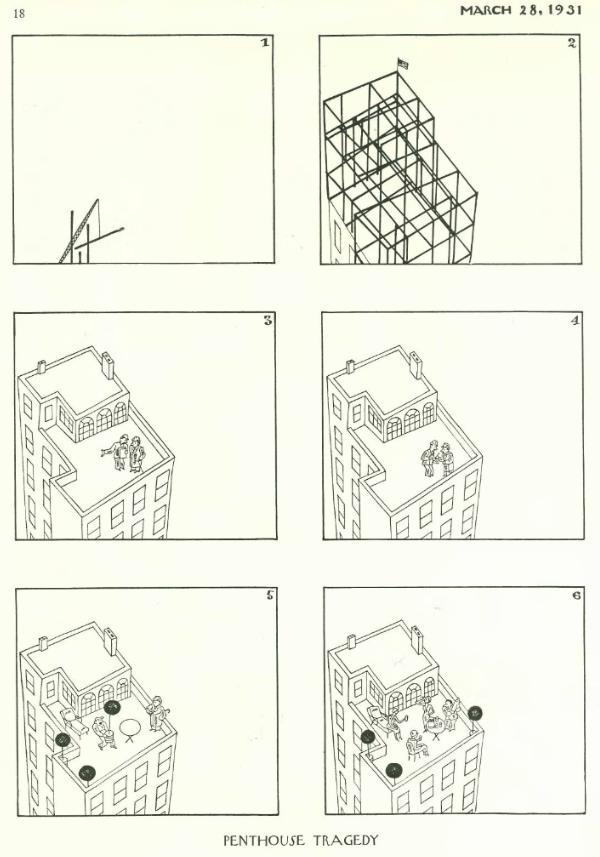

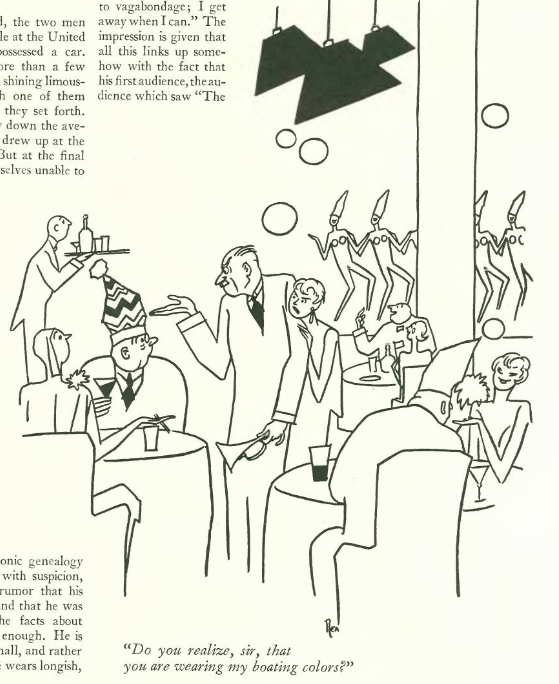

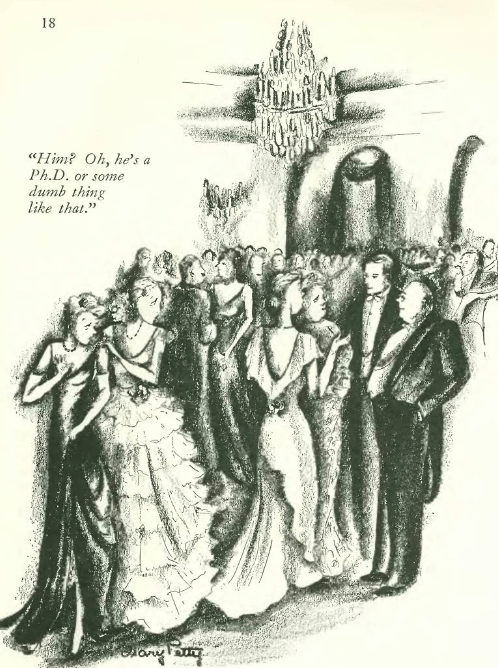

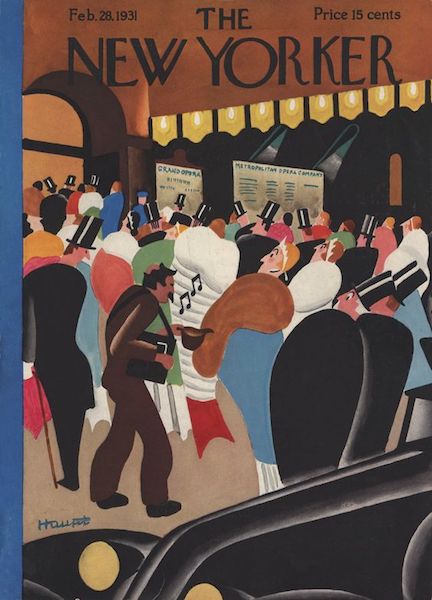

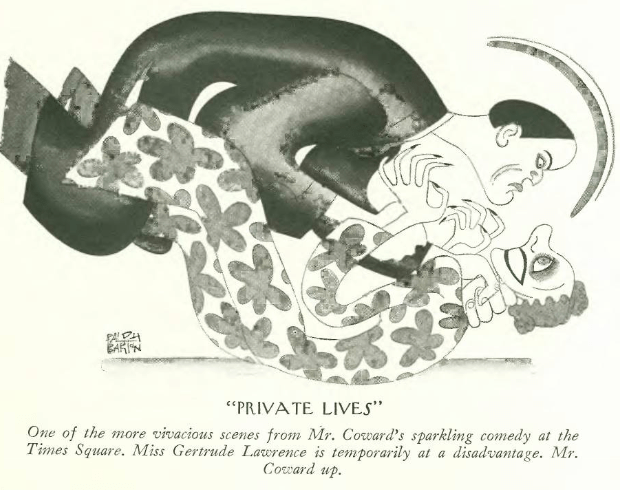

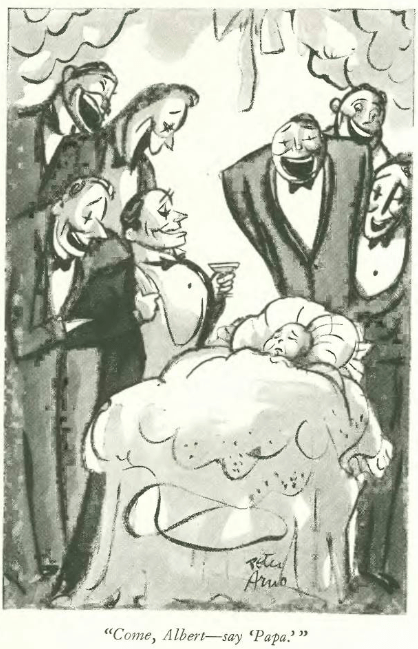

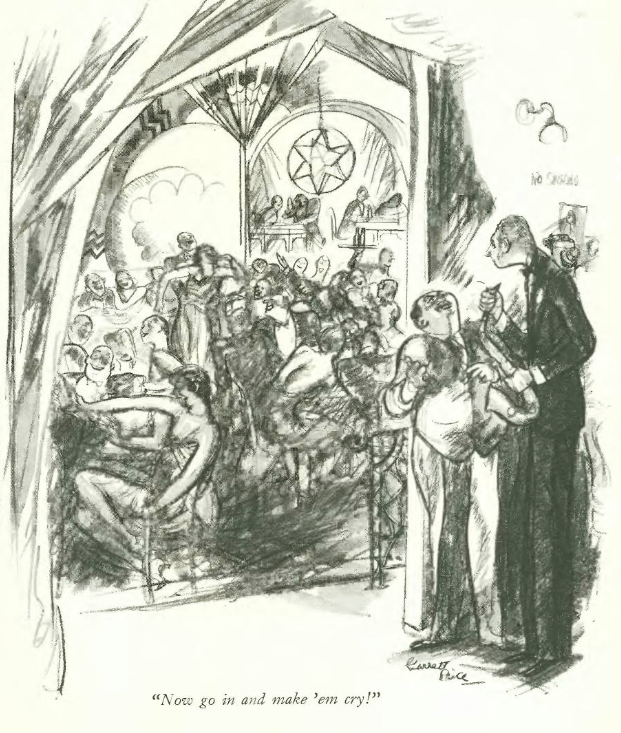

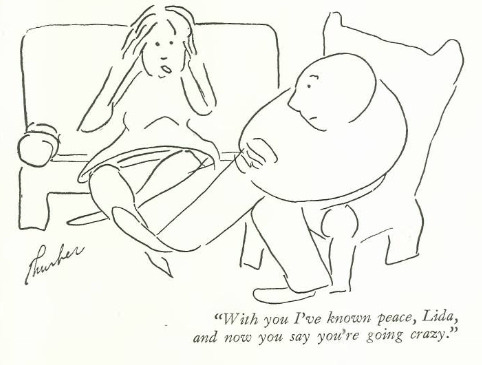

…on to our cartoonists, we begin again with Ralph Barton’s “Hero of the Week”…

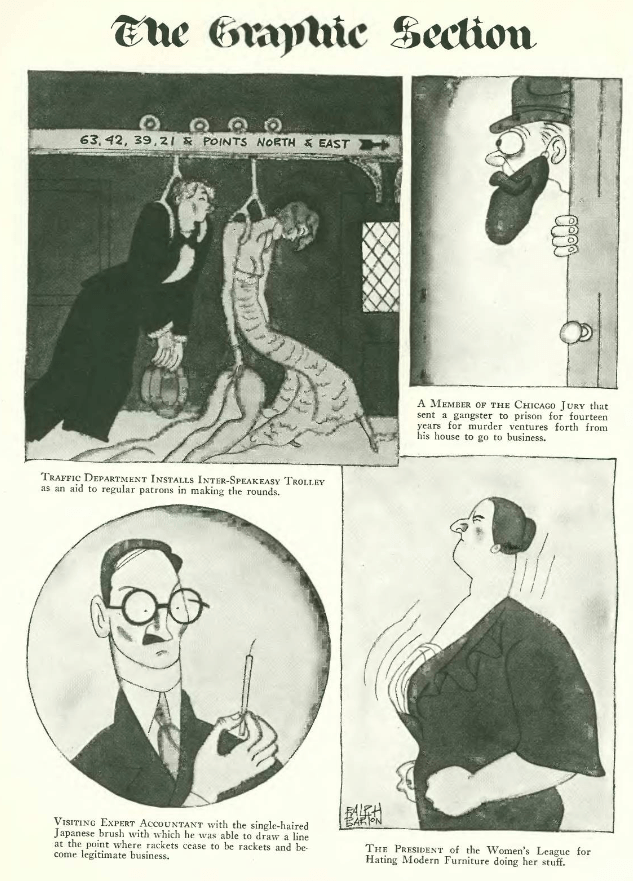

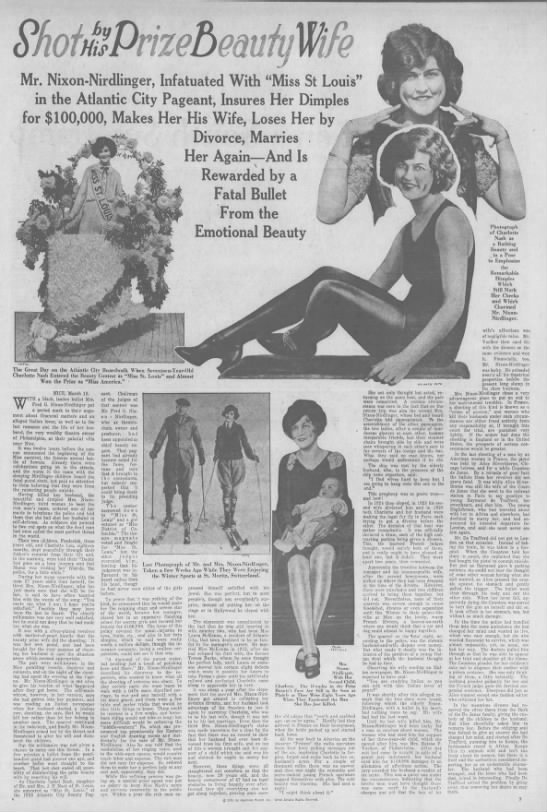

…and Barton’s graphic take on the week’s headlines…

…Carl Rose examined new heights in envy…

…or in the case of Leonard Dove, romance…

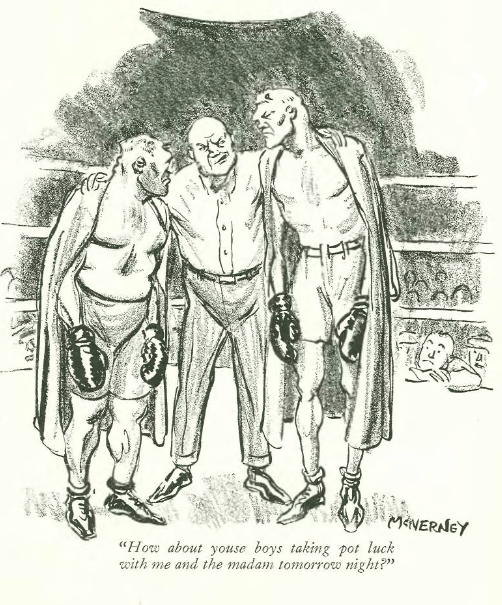

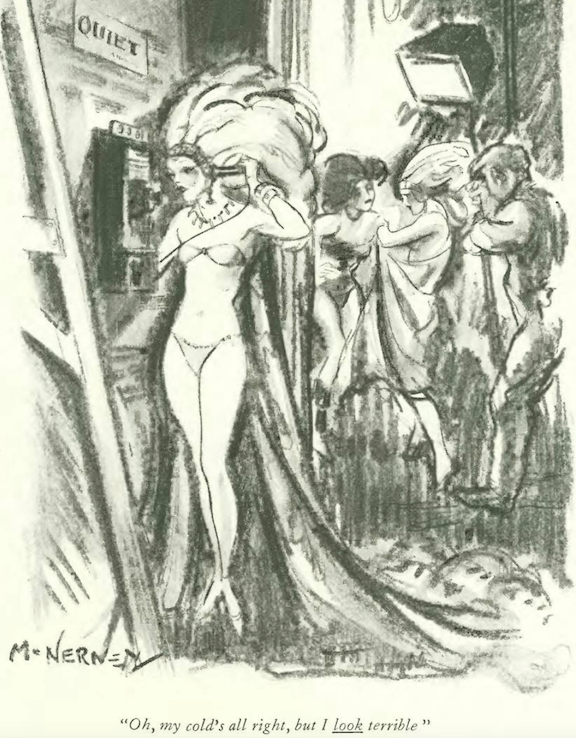

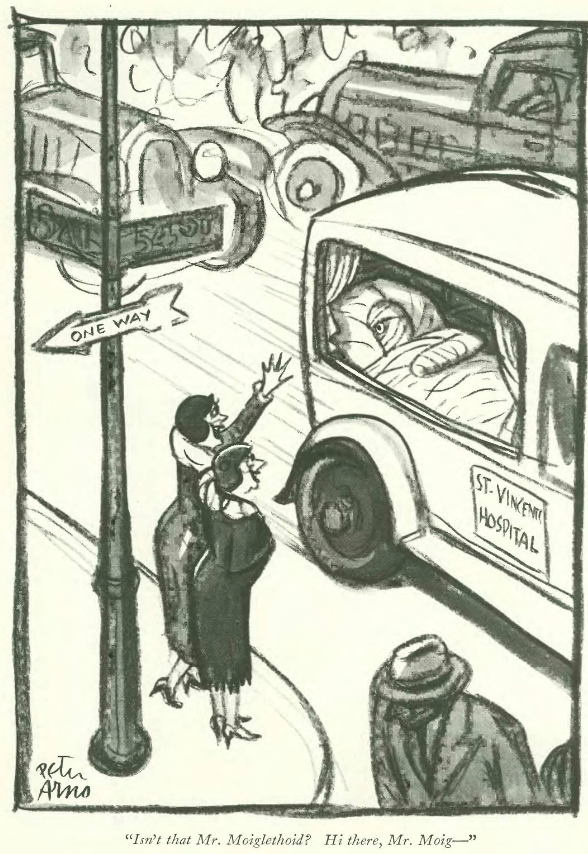

…back to earth, more romance from E. McNerney…

…and below ground, C.W. Anderson showed how romantic notions can go sour, in this case a man who felt duped by those rags-to-riches tales…

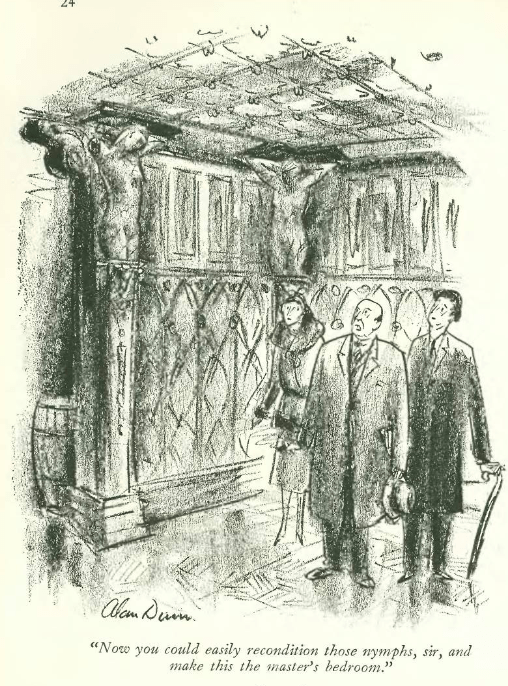

…and we end with Alan Dunn, and a little girl getting an education through the pages of a scandal rag…

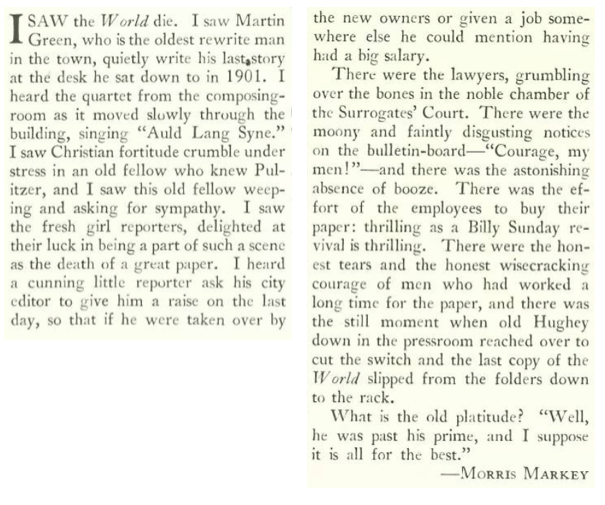

Next Time: Through the Looking Glass…