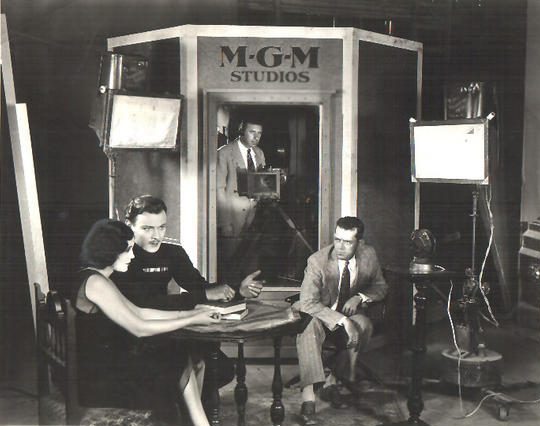

The German actor Emil Jannings was well-known to American audiences when The Blue Angel (Der blaue Engel) premiered at New York’s Rialto Theatre. Although the film was created as a vehicle for the Academy Award-winning Jannings (he won the Academy’s first-ever best actor award in 1929), it was the little-known Marlene Dietrich who stole the show and made it her ticket to international stardom.

New Yorker film critics, including John Mosher, generally found foreign films, particularly those of German or Russian origin, to be superior to the treacle produced in Hollywood, and Jannings was a particular favorite, delivering often heart-wrenching performances in such silent dramas as The Last Laugh (1924) and The Way of All Flesh (1927). In those films he depicted once-proud men who fell on hard times, and such was the storyline for The Blue Angel, in which a respectable professor falls for a cabaret singer and descends into madness.

I was surprised by Mosher’s somewhat tepid review of this landmark film, which was shot simultaneously in German and English (with different supporting casts in each version). He referenced “bum dialogue,” which was doubtless the result of German actors struggling with English pronunciations. Filmed in 1929, it is considered to be Germany’s first “talkie.”

* * *

All Wet

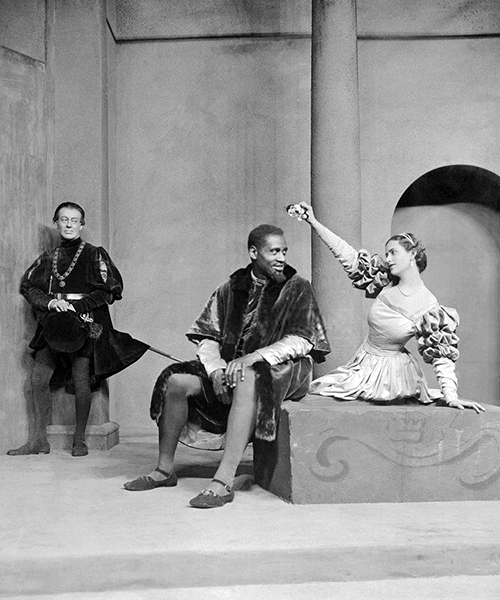

Sergei Tretyakov’s avant-garde play Roar China made an impression on The New Yorker for the striking realism of its set, which featured an 18,000-gallon tank of water onstage at the Martin Beck Theatre. “The Talk of the Town” described some of the demands of the production:

* * *

By Any Other Name

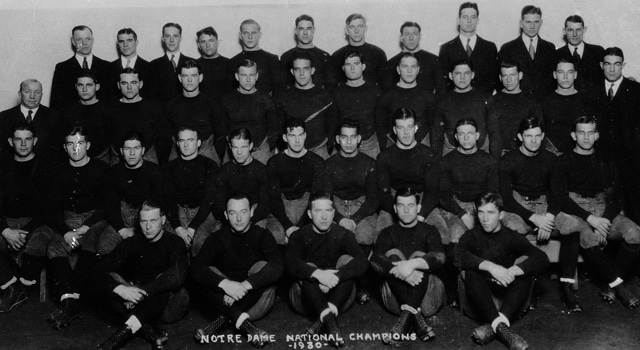

Like many college football teams in first decades of the 20th century, Notre Dame was referred to by a number of nicknames, including the “Fighting Irish.” In this “Talk of the Town” item, however, the team was known as the “Ramblers.” According to the University of Notre Dame, this nickname (along with “The Rovers”) was considered something of an insult: “(Knute) Rockne’s teams were often called the Rovers or the Ramblers because they traveled far and wide, an uncommon practice before the advent of commercial airplanes. These names were also an insult to the school, meant to suggest it was more focused on football than academics.”

* * *

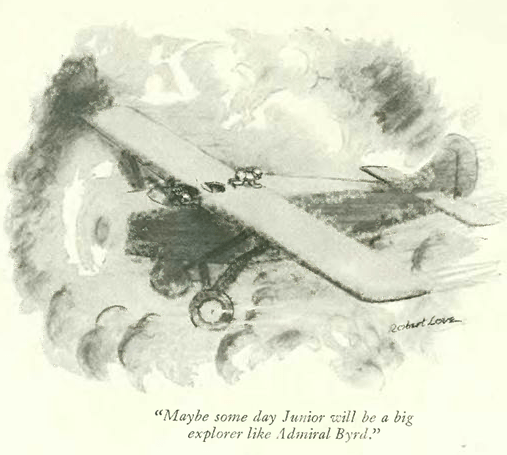

The Wright Stuff

Eric Hodgins penned a profile of aviation pioneer Orville Wright, who just 27 years earlier made a historic “first flight” with his brother, Wilbur, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. An excerpt:

* * *

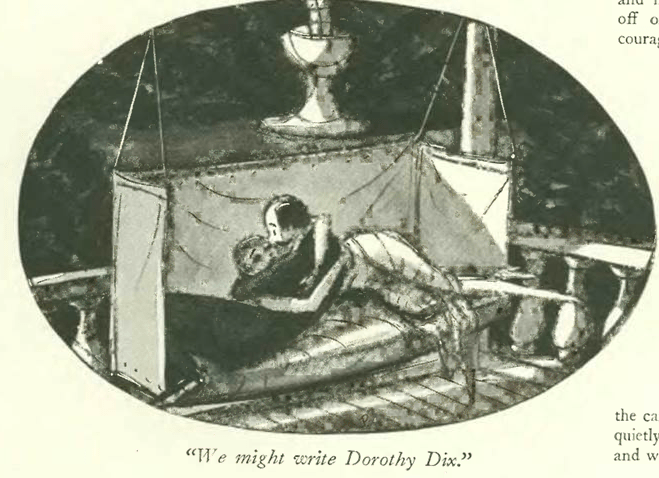

No Love Parade, This

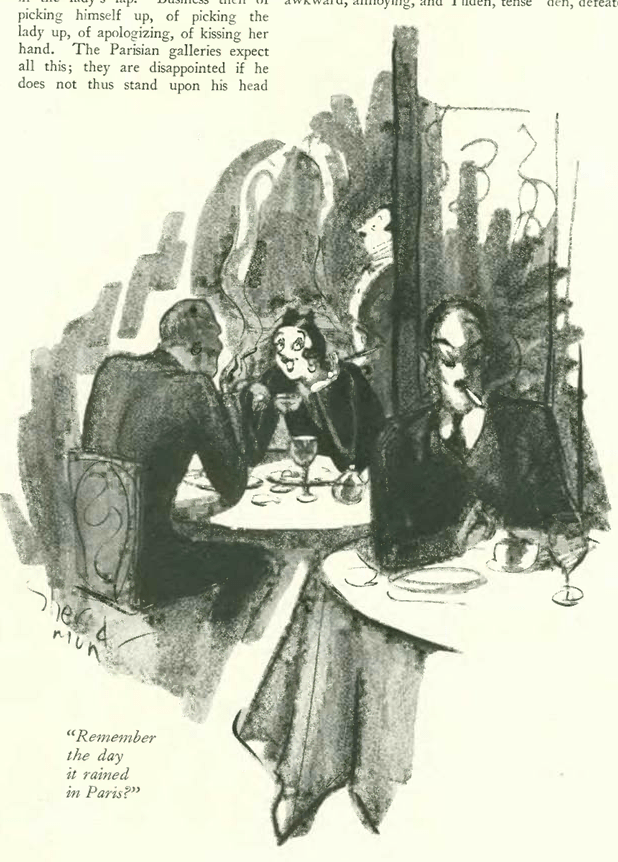

French singer and actor Maurice Chevalier made his Hollywood debut in 1928 and quickly soared to stardom in America. French audiences, however, were not so easily swayed, especially the elite patrons Chevalier faced, alone on the stage, at the cavernous Théâtre du Châtelet. Janet Flanner explained in this dispatch from Paris:

* * *

Man’s Best Friend

The New Yorker’s book section recommended the latest from Rudyard Kipling, Thy Servant a Dog…

* * *

Fun and Games

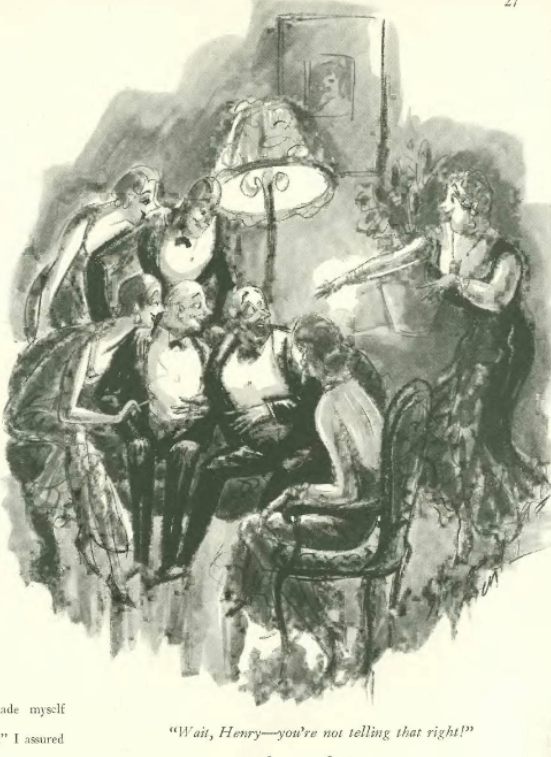

As an extension to her fashion column, Lois Long shared some recommendations for holiday cocktail-party games:

* * *

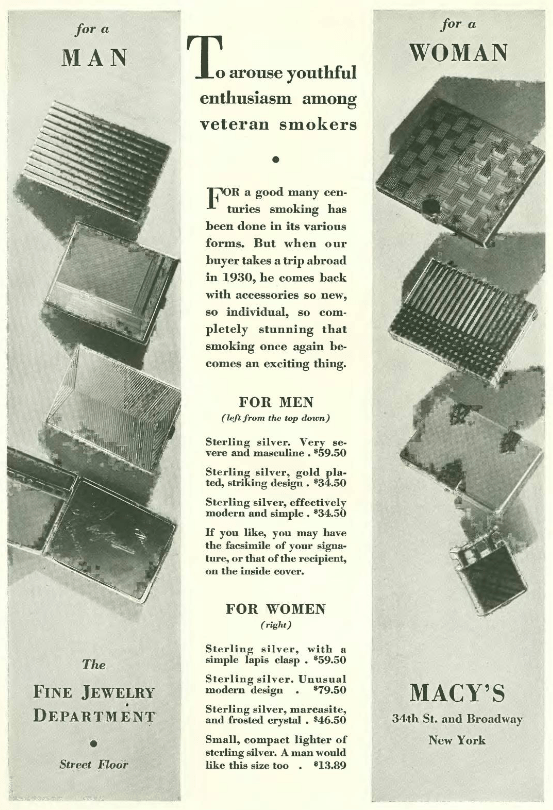

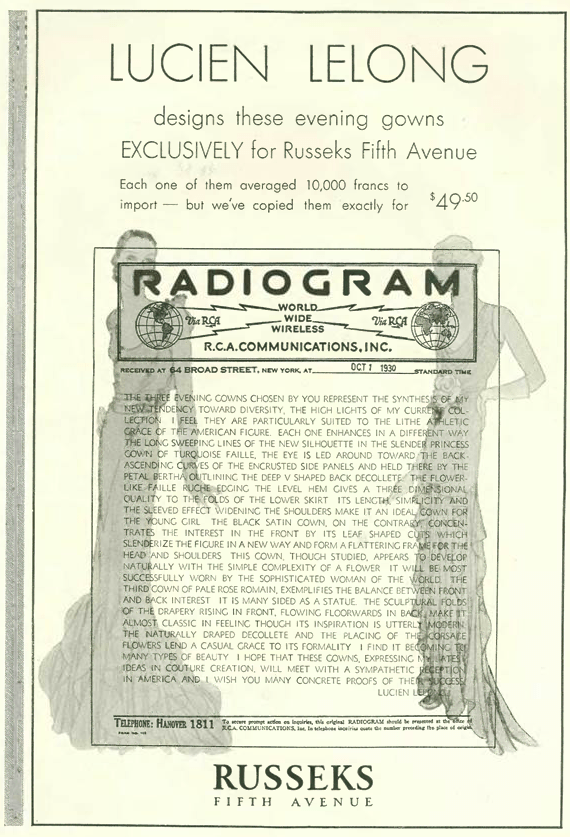

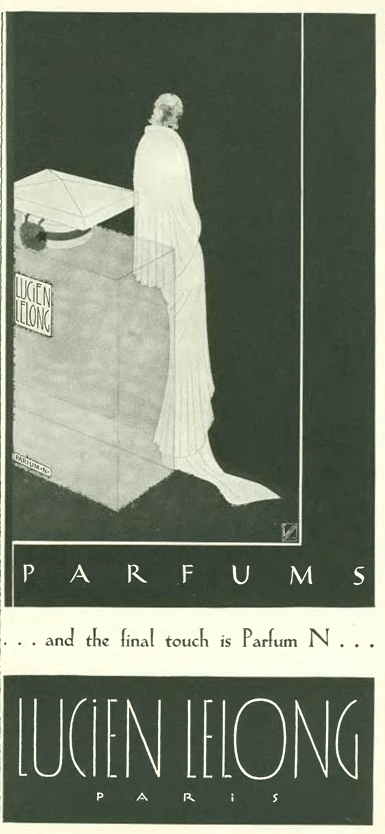

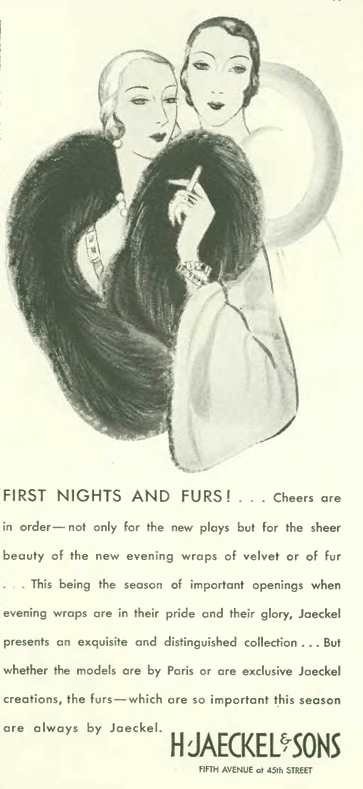

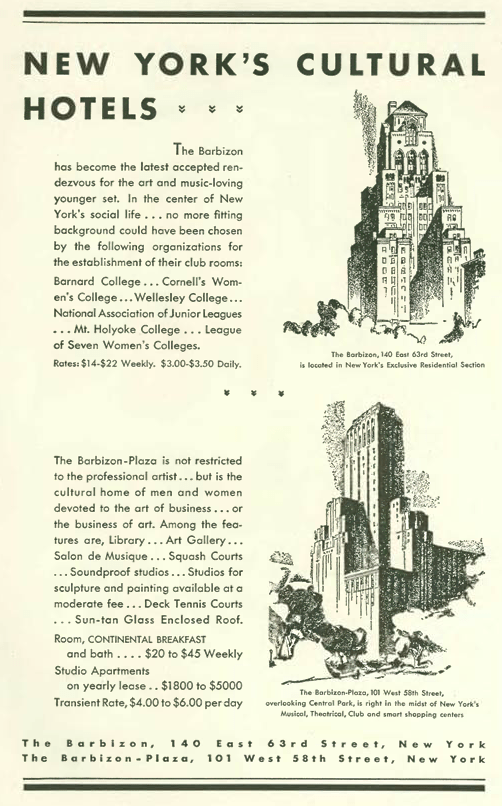

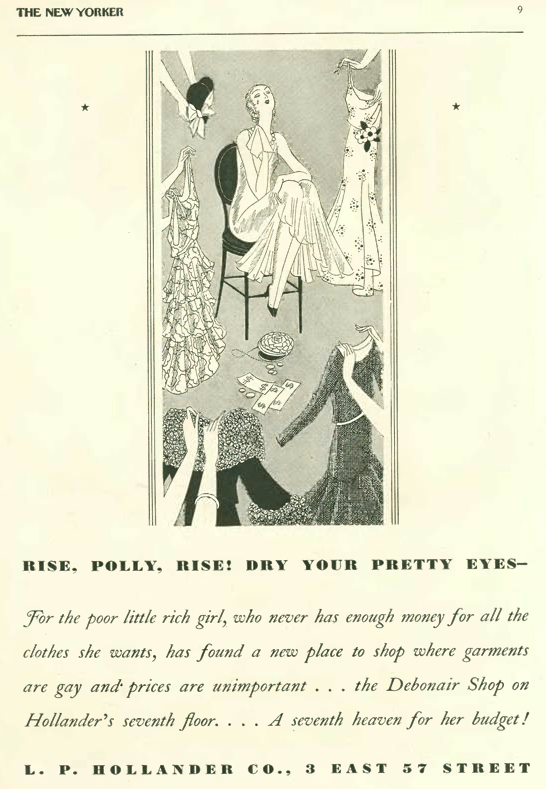

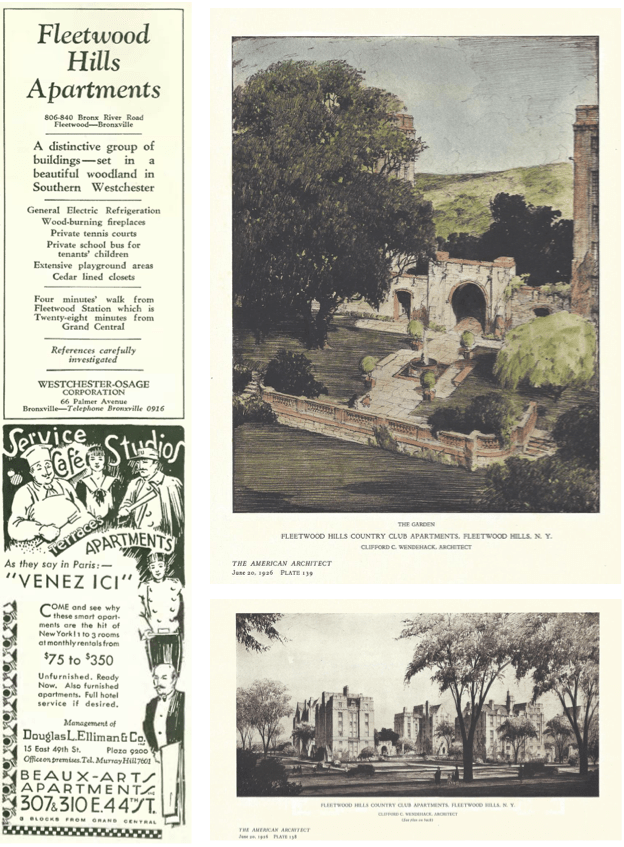

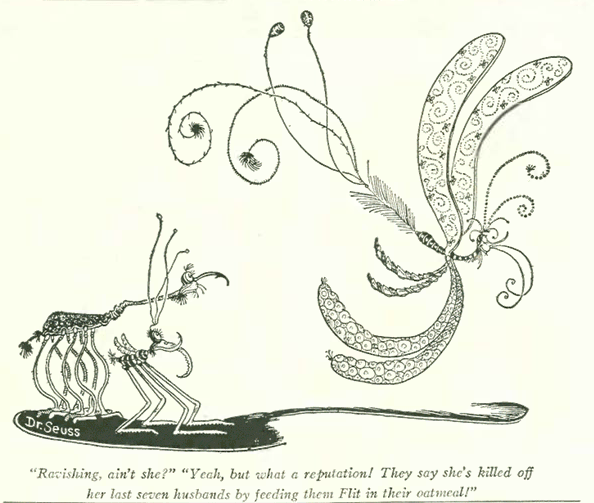

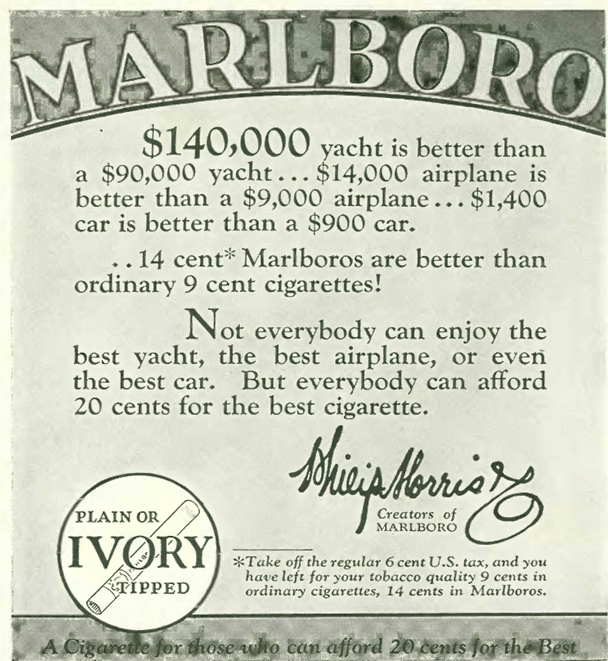

From Our Advertisers

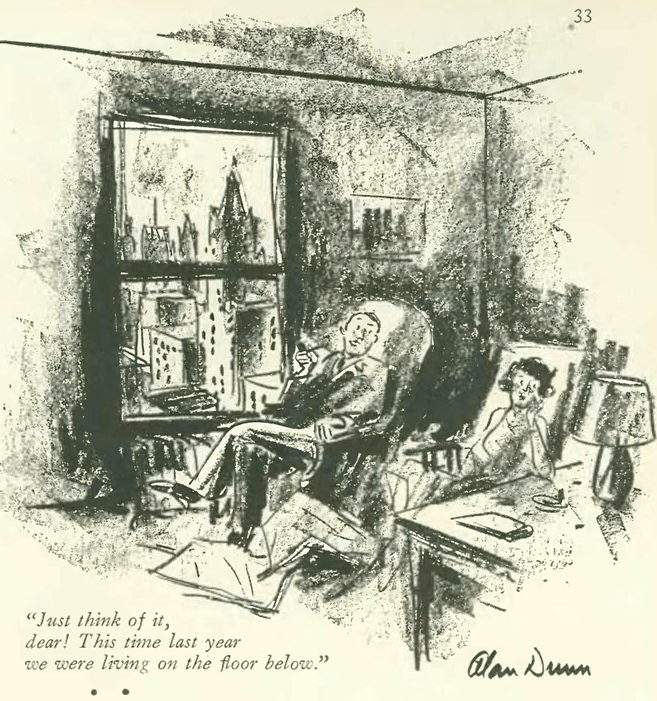

We start with this ad from Horace Liveright promoting Peter Arno’s third cartoon collection, Hullaballoo, featuring one of Arno’s leering old “Walruses”…

…Doubleday Doran offered a few selections for last-minute Christmas shoppers, led by the Third New Yorker Album…

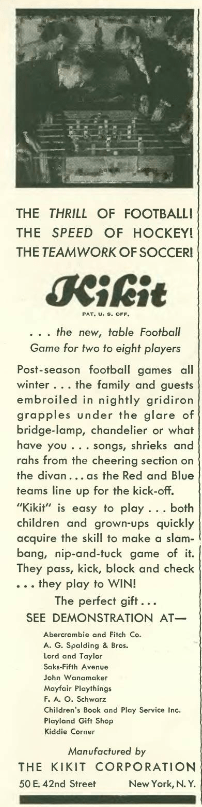

…The UK’s Harold Searles Thorton invented the table top game we now call “foosball” in 1921 and had it patented in 1923. Below is possibly the game’s first appearance in the U.S. — an ad for a “new” game called “Kikit.” Foosball would be slow to catch on, but would rapidly gain popularity in Europe in the 1950s and in the U.S. in the 1970s…

…Horace Heidt and his Californians were doing their best to make the season bright at the Hotel New Yorker…

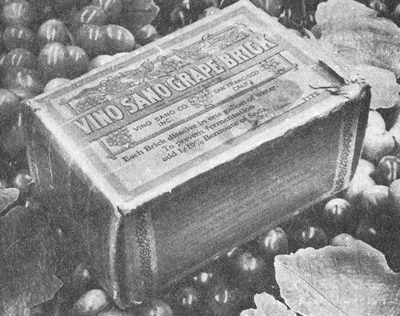

…Peck & Peck tried to make the most of Prohibition by stuffing scarves and other wares into empty Champagne bottles…

…and Franklin Simon reminded readers that it would be a “Pajama-Negligee Christmas,” whatever that meant…

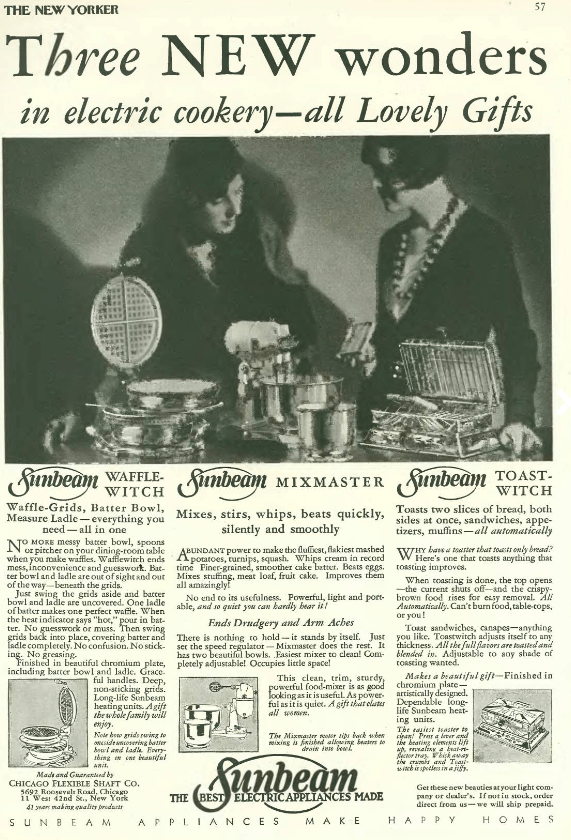

…pajamas and negligees were doubtless preferable, and more romantic, than this array of kitchen appliances…

…whatever the holiday revelry, the makers of Milk of Magnesia had our backs…

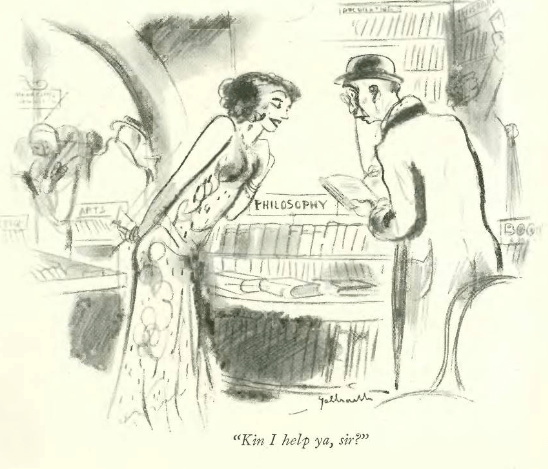

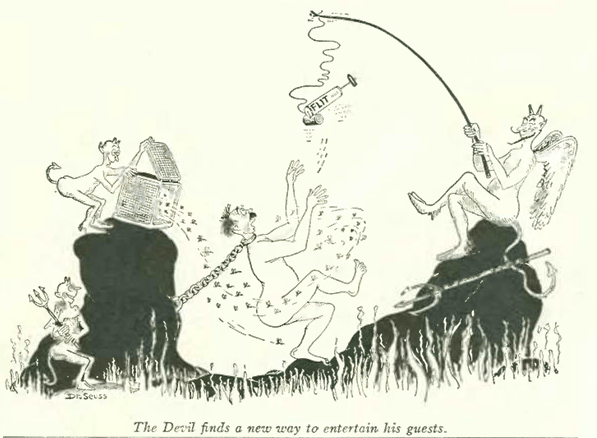

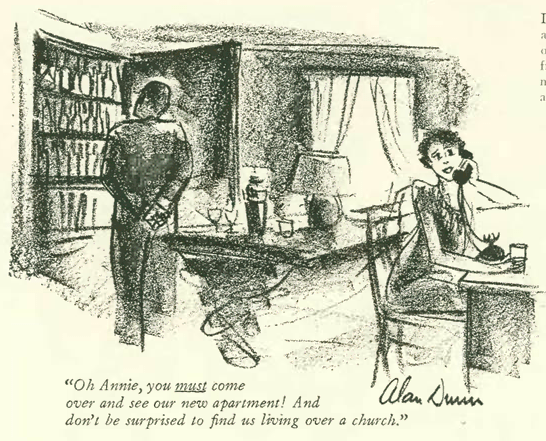

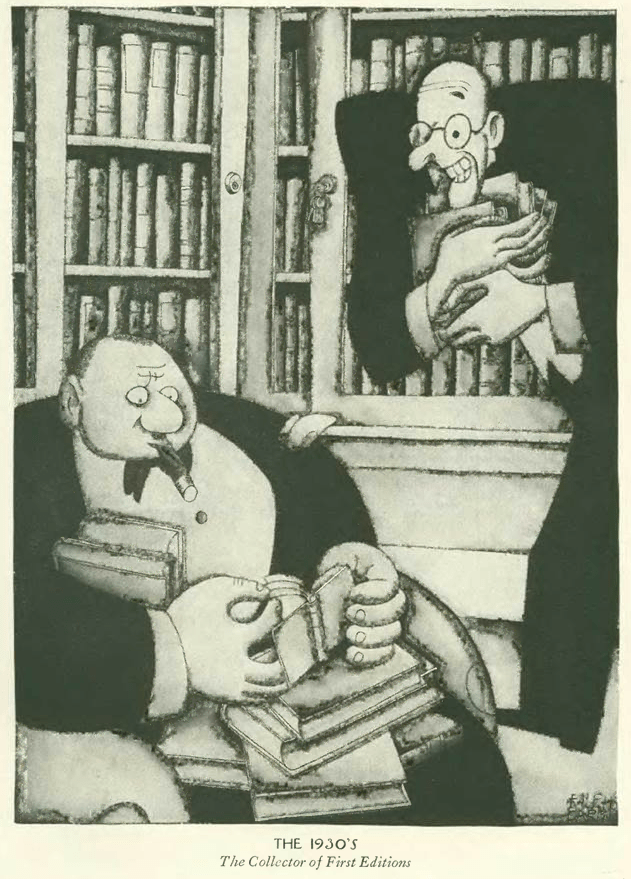

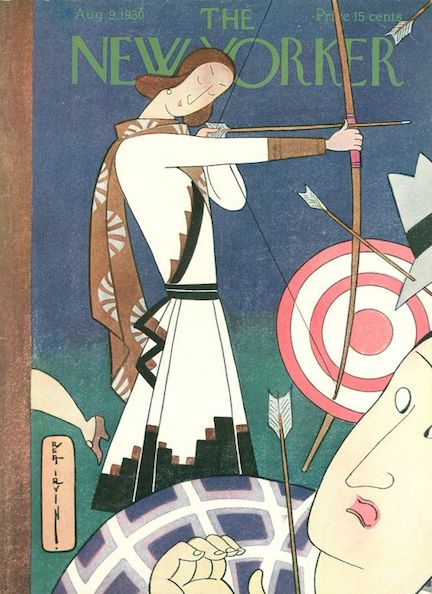

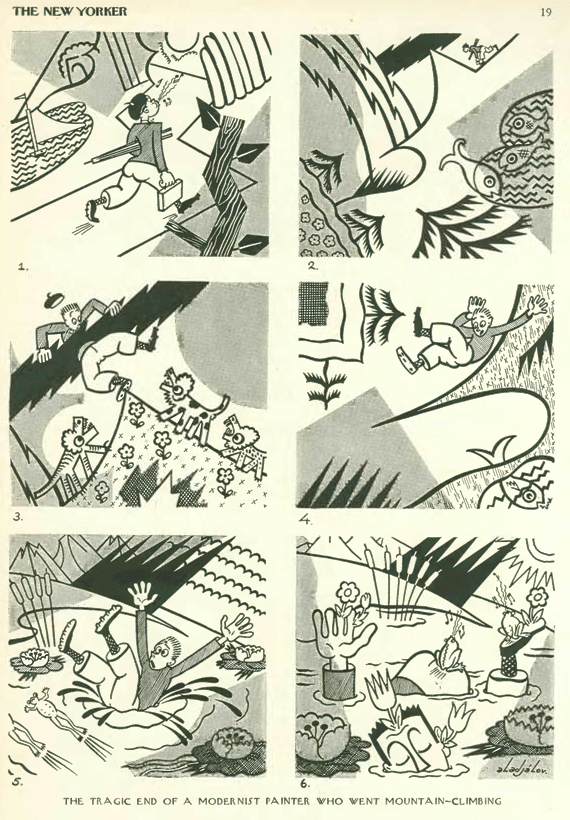

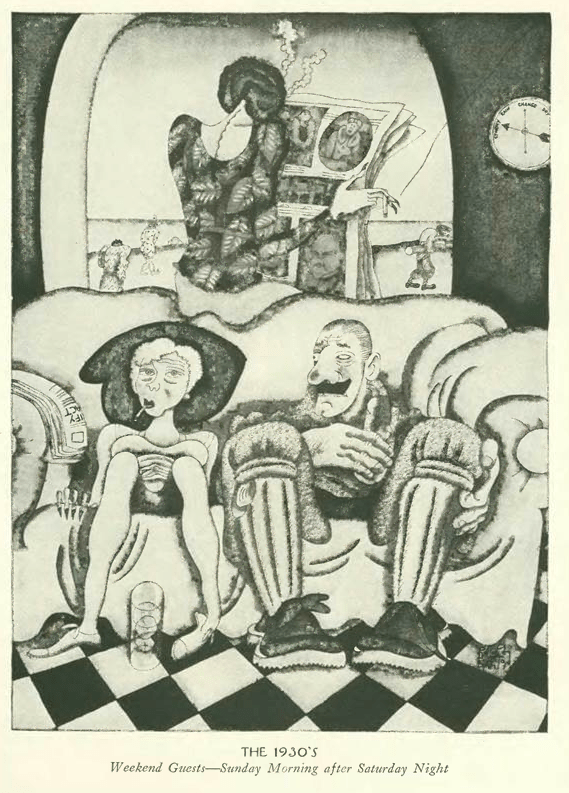

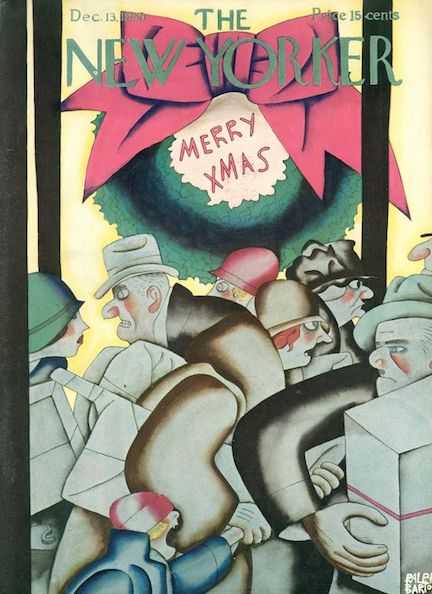

…on to our cartoonists, Julian De Miskey and Constantin Alajalov contributed spot drawings to mark the season…

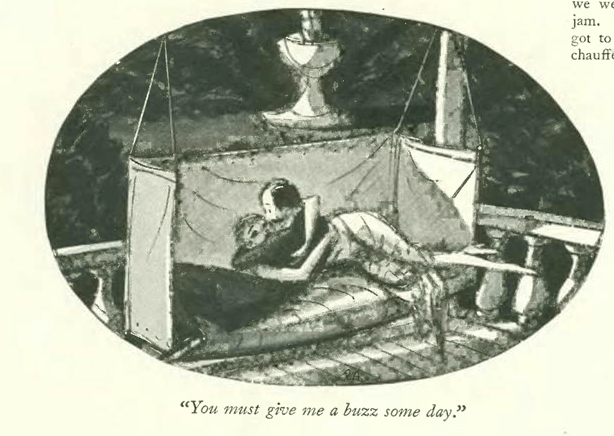

…A.S. Foster contributed two cartoons to the issue…

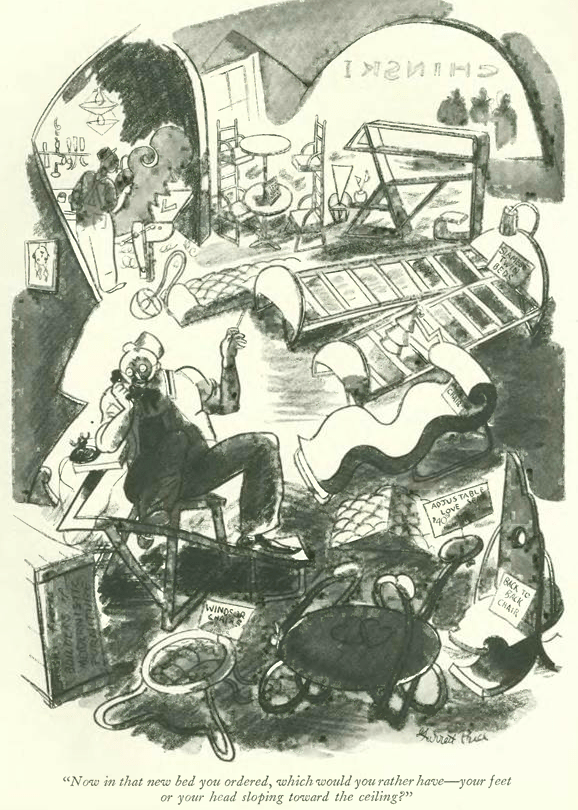

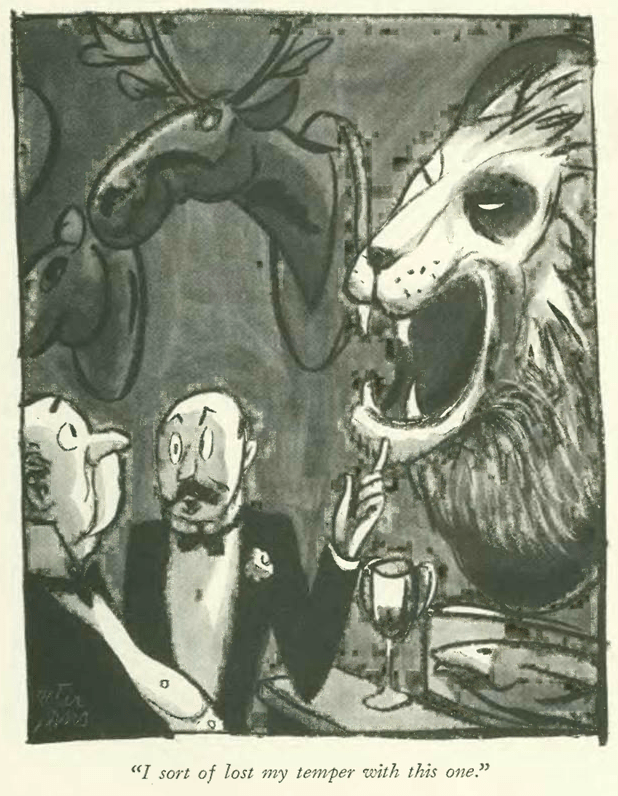

…Gardner Rea, a full-pager…

…Leonard Dove, possibly having some fun with playwright Marc Connelly…

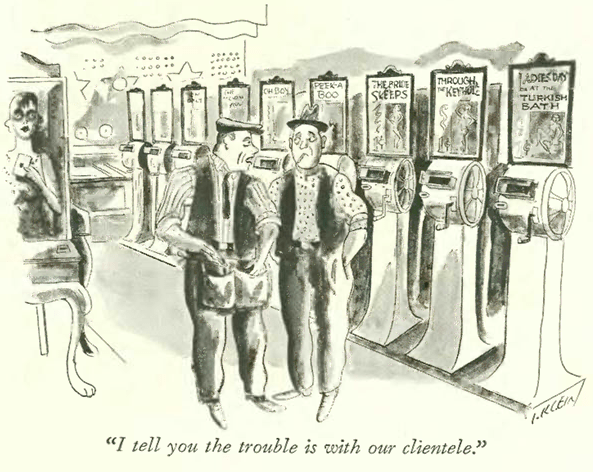

…Isadore Klein demonstrated the fun to be had with a kiddie scooter, before they had motors…

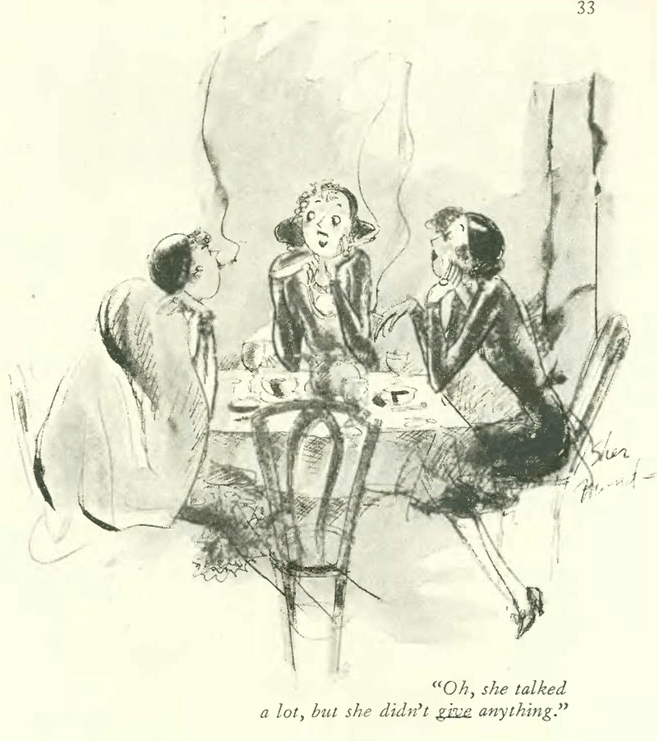

…and we close with John Reynolds, and some bad table manners…

Next Time: Happy Holidays…