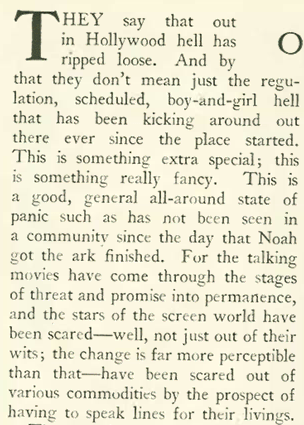

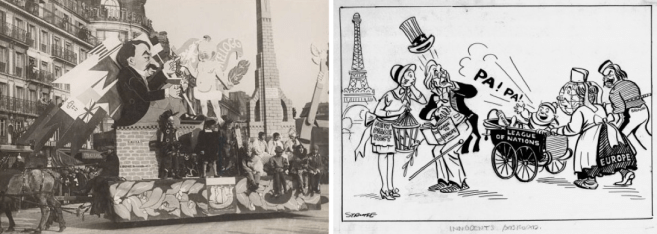

In July of 1928, war was officially banned from the earth. Or so it was hoped when the Kellogg–Briand Pact became effective on July 24, 1929.

Also known as the “Pact of Paris” and more officially the “General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy,” its authors, United States Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg and French foreign minister Aristide Briand, gathered world powers in Paris on Aug. 28, 1928 to sign a treaty that denounced the use of war and called for the peaceful settlement of all future disputes. The New Yorker, in the opening “Notes and Comment” section of “The Talk of the Town,” took its usual “What, Me Worry?” approach to world affairs, finding the whole thing unnecessary given that (in its view) Europe was already a peaceful, even benign continent:

In January 1929 the U.S. Senate officially ratified the Kellogg–Briand Pact with a nearly unanimous vote, 85-1. John James Blaine, senator from Wisconsin, cast the lone dissenting vote (although four years later Blaine would author another piece of legislation that would have a much greater impact, at least at the time: the 21st Amendment, which ended Prohibition).

Another item in “The Talk of the Town” made further reference to the pact…

…and Howard Brubaker, in his column “Of All Things,” made special mention of the Sino-Soviet border conflict in referencing the pact:

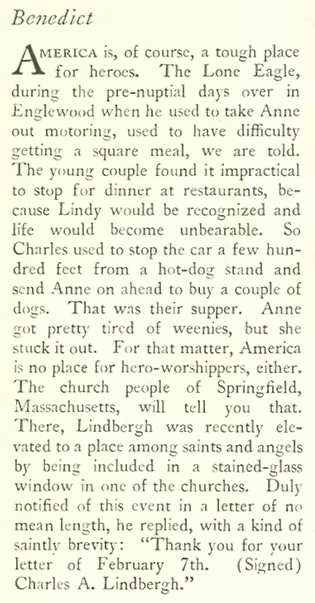

Brubaker mockingly suggested that the pact marked the beginning of a thousand years of peace, an inadvertently prescient remark considering that in less than four years Hitler would seize power in Germany and announce the beginning of his “Thousand Year Reich” — which we know was quite the opposite of peace. Brubaker was also off the mark with this crude observation:

Just two years after Brubaker wrote those words, Japan would invade Manchuria. And only a decade would pass before Germany and Russia would invade Poland and ignite the biggest war of all time.

Although the pact was ridiculed for its perceived naïveté, and for the fact that it did not prevent the largest war in human history, some modern scholars see otherwise. Political scientists Oona A. Hathaway and Scott J. Shapiro observed (in 2017) that the pact “catalyzed the human rights revolution, enabled the use of economic sanctions as a tool of law enforcement, and ignited the explosion in the number of international organizations that regulate so many aspects of our daily lives.” In his recent book Enlightenment Now, Steven Pinker notes “virtually every acre of land that was conquered after 1928 has been returned to the state that lost it. Frank Kellogg and Aristide Briand may deserve the last laugh.”

* * *

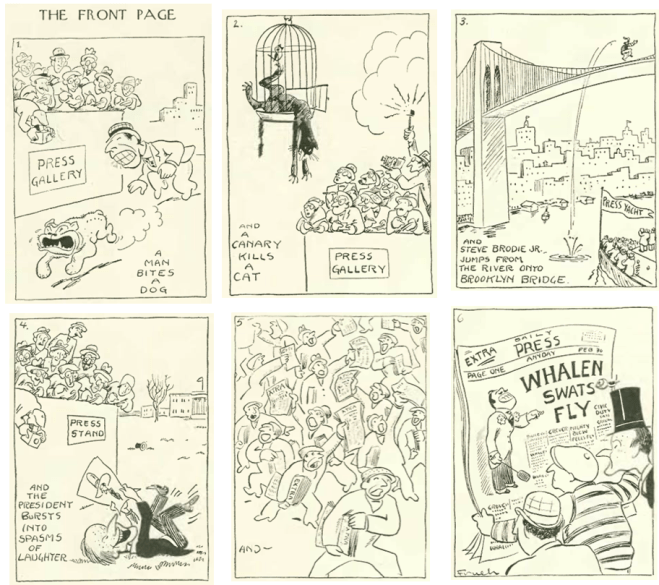

Gallows Humor

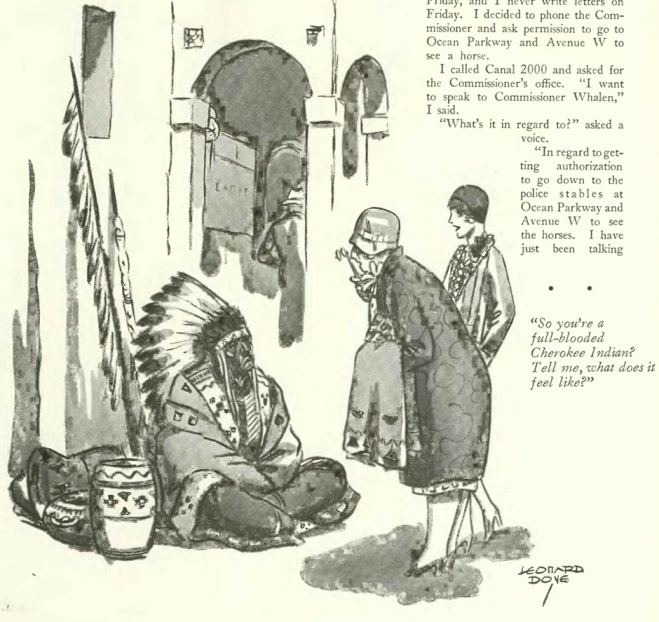

Other items in “The Talk of Town” included this brief anecdote, which I doubt many would find humorous today:

* * *

On The Bowery

In the “Reporter at Large” column, Niven Busch Jr. paid a visit to “The Yellow Bowery,” as the piece was titled. Notable in this article (and in Brubaker’s quip above) is the use of term “Chinaman,” a term considered offensive today but in the 1920s was used indiscriminately for East Asians. Here it seems pejorative:

Busch’s piece was rife with stereotypes…

…and referenced the unsolved Bowery murder of 19-year-old Elsie Sigel, a missionary in Chinatown who was found in a trunk, strangled, in 1909…

* * *

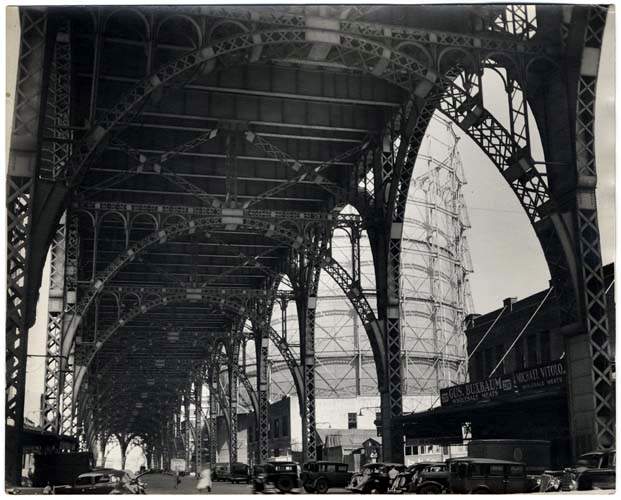

It Grows on You

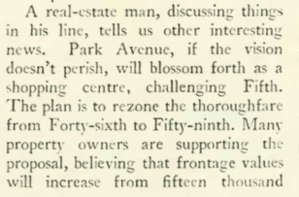

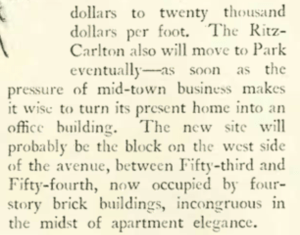

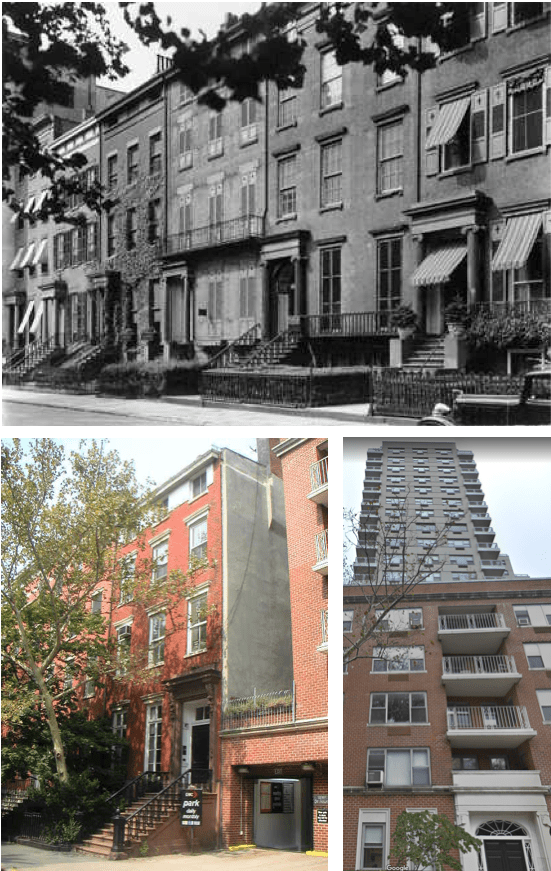

The rapid demolition of old New York was a recurring theme in The New Yorker of the 1920s, the magazine often wavering between nostalgia and the thrill of the new. No place was perhaps more sacred than the stately row houses of Washington Square. When news circulated that a section consisting of the old Rhinelander mansion would soon fall (for the sake of a new apartment building), “Talk” tried its best to process the change:

* * *

Old Boy

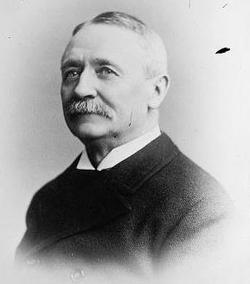

In one of my recent posts (Not Your Grandpa’s Tammany Hall) I noted a “Talk” item that described the new Tammany headquarters. In the August 3 issue the magazine introduced the patriotic society’s new leader, John Francis Curry, in a profile written by Henry F. Pringle. In the piece, titled “Local Boy Makes Good,” Pringle suggested that Curry’s old-fashioned approach to politics stood in contrast to the new image Tammany Hall was attempting to project:

Curry’s tenure would end abruptly in 1934 — the first Tammany boss to be booted out by his own followers. Curry made some bad decisions during a time when the political winds were shifting away from machine politics. It was under his leadership that Tammany backed Al Smith over the reform-minded Franklin Roosevelt for the 1932 Democratic presidential nomination. That same year, Tammany-backed New York Mayor Jimmy Walker would be forced from office amid scandal.

* * *

Well, She Didn’t Write the Script

We all know Greta Garbo as one of the greatest film stars of classic Hollywood. Her mysterious aura and subtlety of expression are still lauded by film critics today. The New Yorker, however, never seemed particularly enamored of the star’s performances. Here is a review of her 1929 silent film, The Single Standard:

* * *

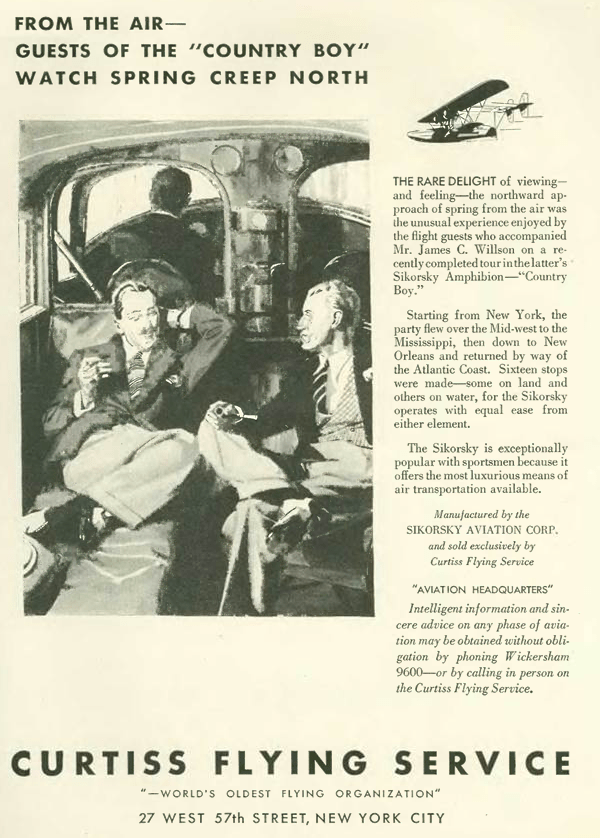

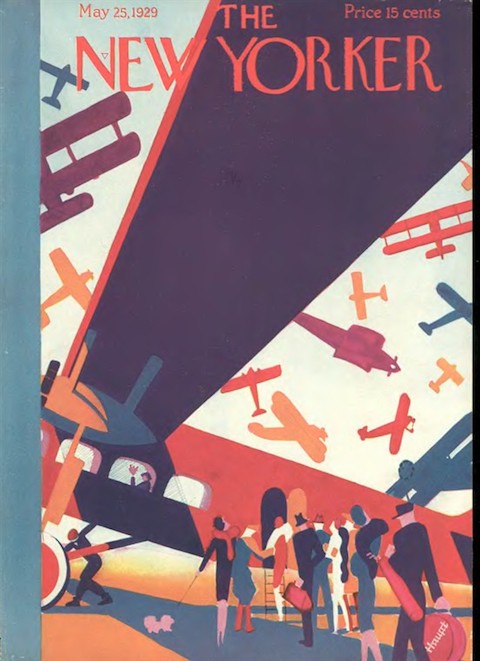

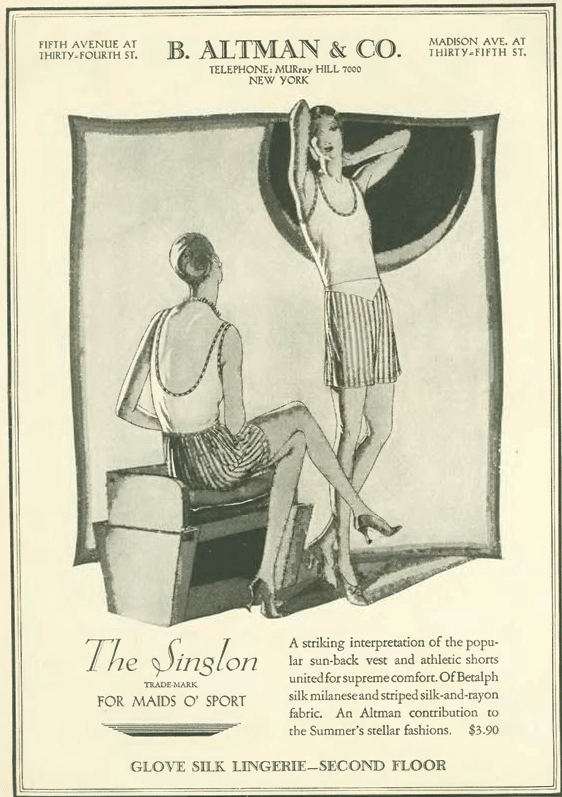

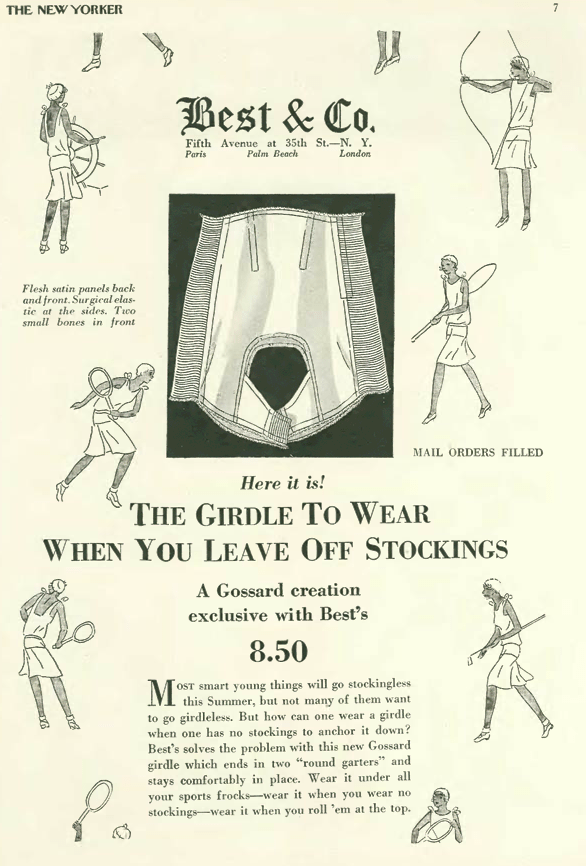

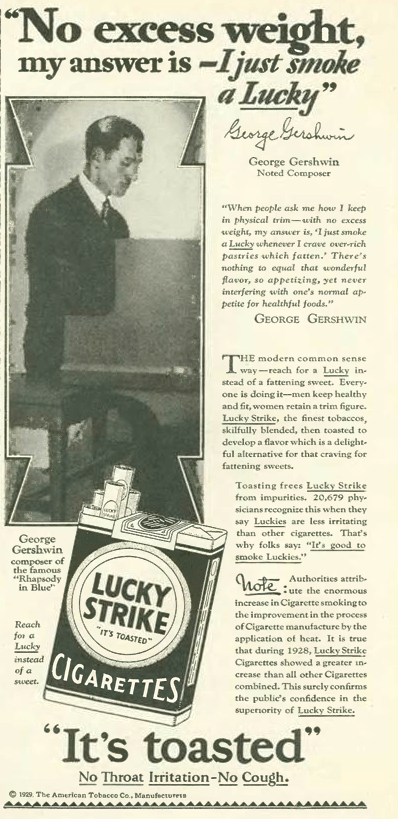

From Our Advertisers

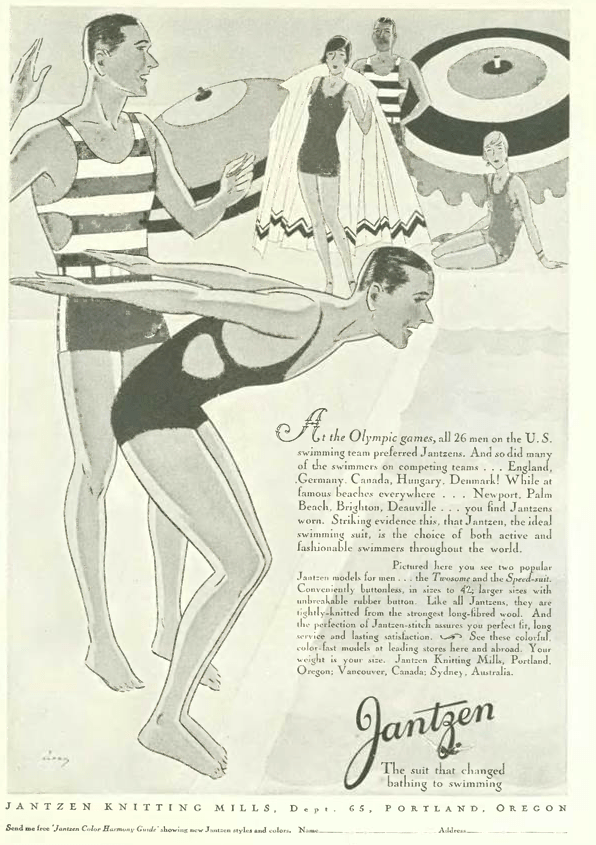

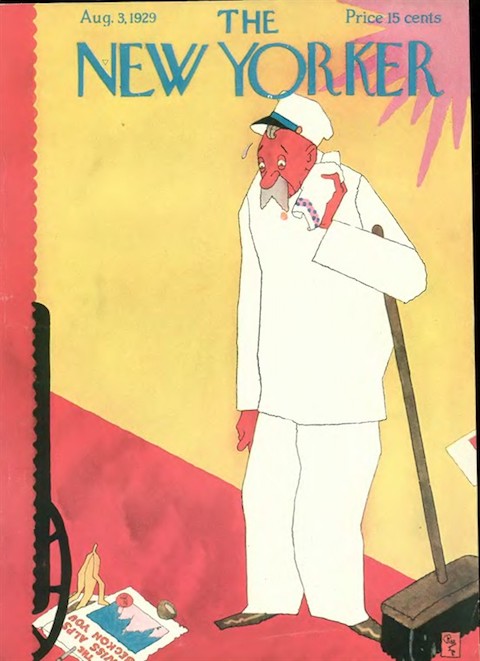

Our first advertisement (image at right) is from the back pages of the Aug. 3 issue. It announced the opening of Long Island’s Atlantic Beach Club, which featured the entertainment of Rudy Vallée and his orchestra…

…a brand-new car—The Ruxton— was introduced to New Yorker readers in this color advertisement that spanned four pages (click image to enlarge)…

…produced in 1929-30 by the New Era Motors company of New York, the car was marketed for its innovative front-wheel drive and its distinctive low profile (a feat accomplished by eliminating the drive shaft to the rear wheels). While most cars in the late 1920s had an average height of 6 feet (1.8 meters); the Ruxton was less than 4 and half feet (1.3 meters) high. Producers of the car hoped to sell the rights of the Ruxton to an established car manufacturer. Moon Motors of St. Louis built just 96 of the cars during regular production (from June to October, 1930) before the whole deal fell apart…

…if you were one of the fortunate few to own a Ruxton, you might take it for a spin on the Lincoln Highway…or maybe not. Despite the appearance of this ad, a fully paved, transcontinental highway was still an incomplete dream in 1929. Although sections of the road were quite smooth from New York to Omaha, further west things could get a bit bumpy, especially on the unpaved stretches. However, as the ad claims, what really made the road viable was the availability of regularly spaced gas stations along the way…

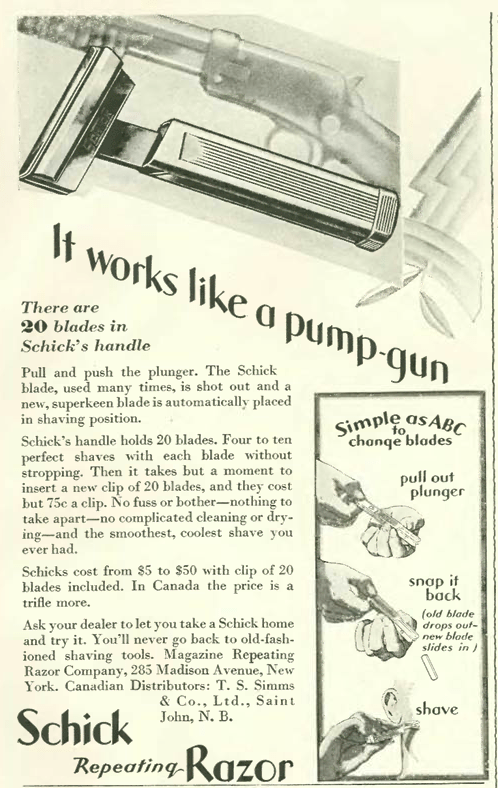

…I liked this ad for its sheer complexity…

…and then we have this ad from Saks, which somehow conflated new shoes with an intimate encounter with Aphrodite.,,

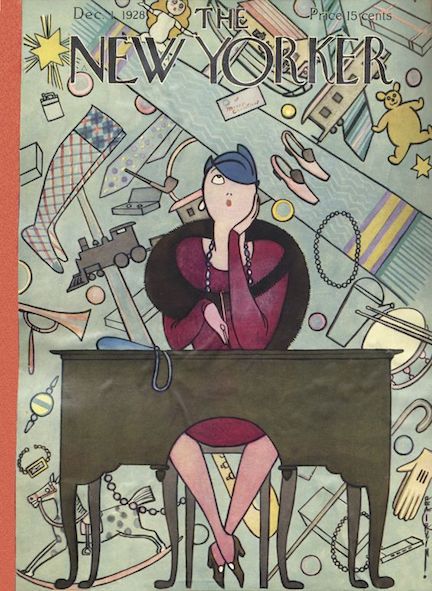

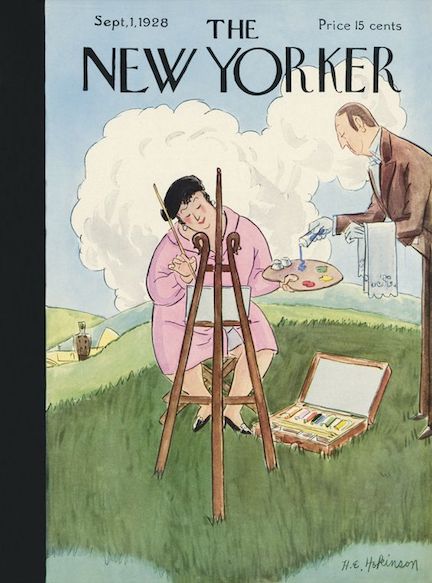

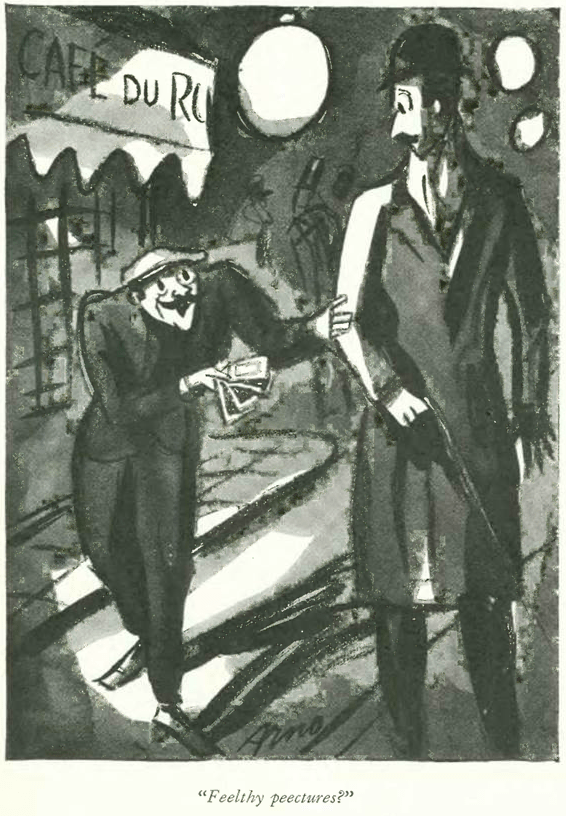

…on to our cartoonists, we have Helen Hokinson’s observations at “Old Narragansett…

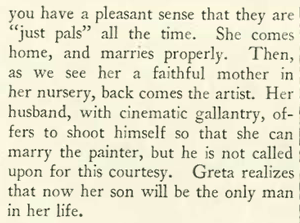

…while out to sea, Alan Dunn found humor in a sensitive swabbie…

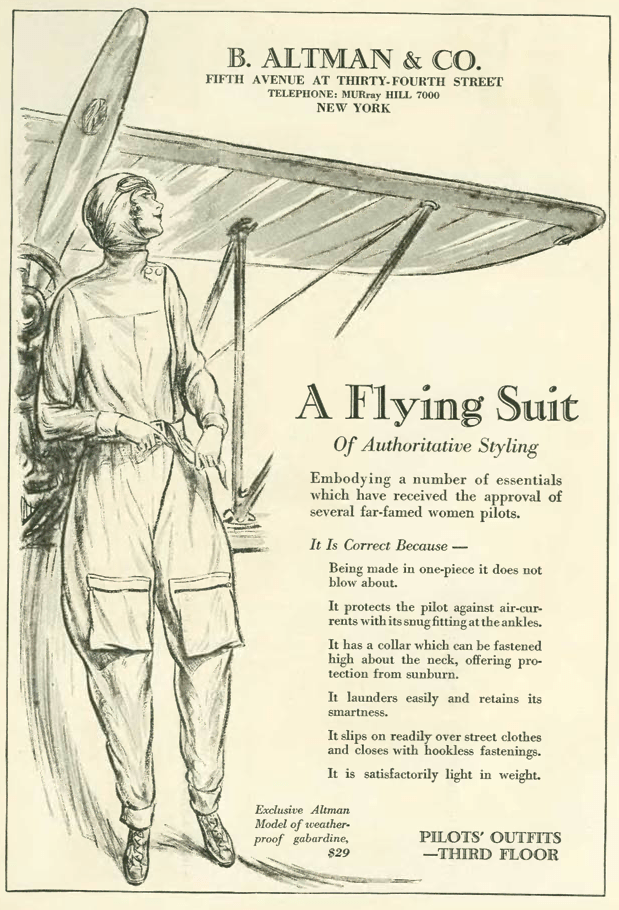

…Alice Harvey observed those still skeptical of human flight…

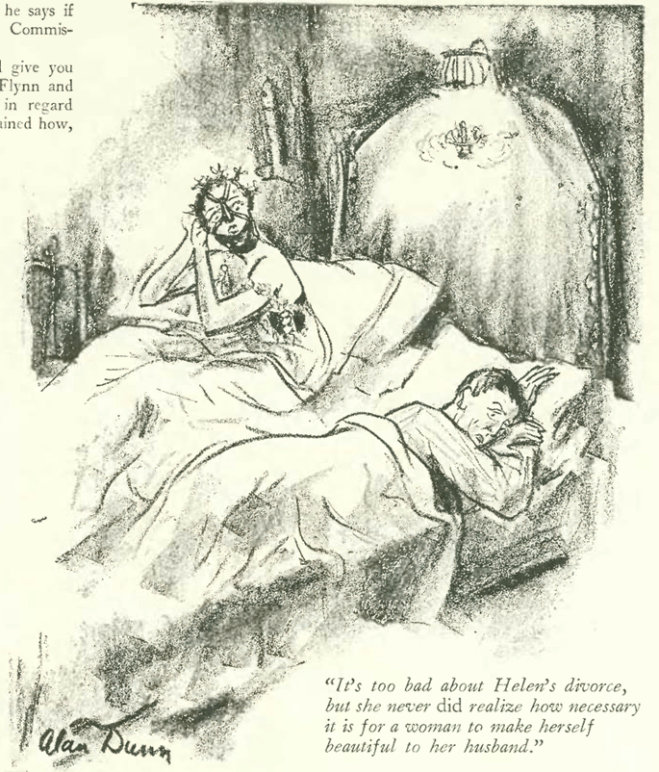

…Perry Barlow peeked in on a moonstruck woman…

…and finally, Isadore Klein visited an antique shop…

Next Time: The Last Summer…