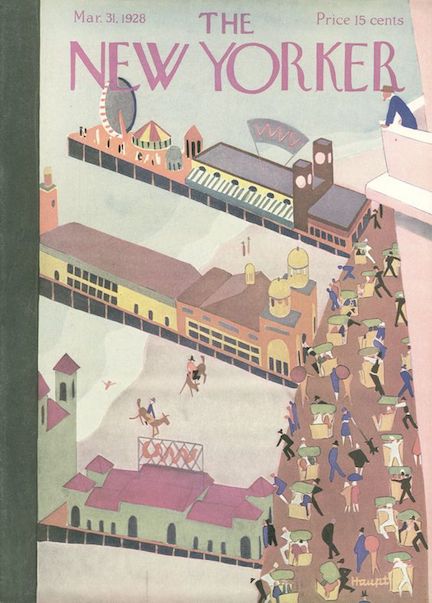

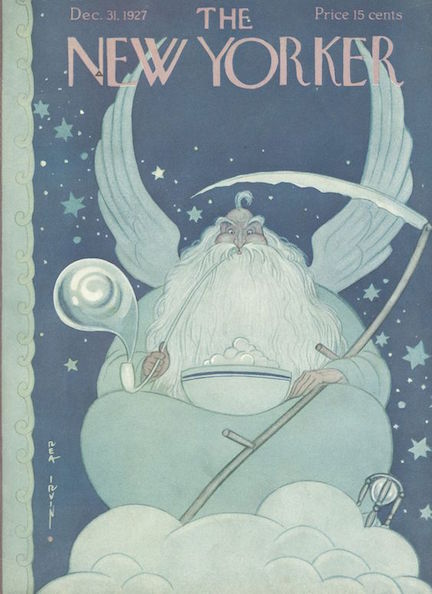

Like many publications, there are defining moments in the New Yorker’s history that make the magazine what it is today.

In a post more than two years ago I wrote about Ellin Mackay’s pivotal essay, “Why We Go To Cabarets: A Post-Debutante Explains.” The debutante daughter of a multi-millionaire (who threatened to disinherit her due to her romance with Irving Berlin), Mackay explained that modern women were abandoning social matchmaking in favor of the more egalitarian night club scene. Mackay’s essay provided a huge boost to the struggling New Yorker, which had dipped to less than 3,000 subscribers in August 1925. A more recent post, “A Bird’s Eye View,” noted how a short story by Thyra Samter Winslow opened the door to serious fiction in the magazine.

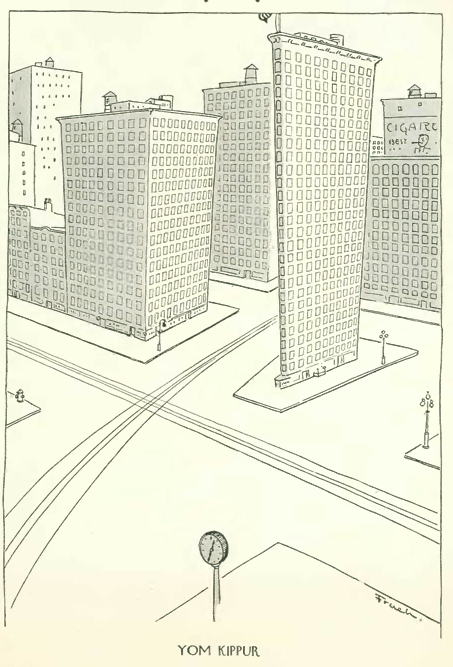

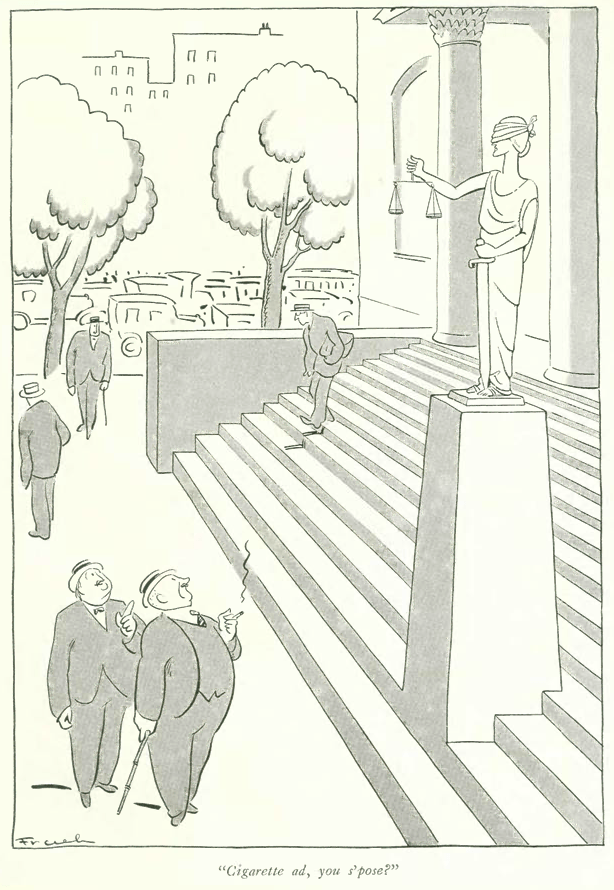

The Dec. 8, 1928 issue was significant for a cartoon by Carl Rose that appeared on the bottom of page 27:

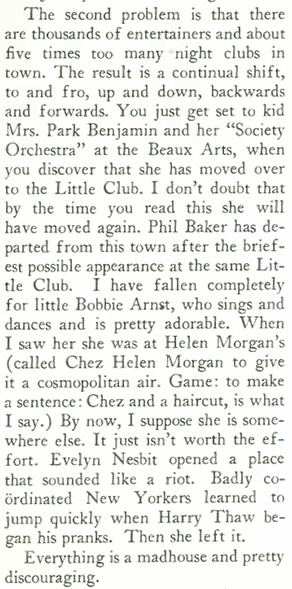

It remains one of The New Yorker’s most famous cartoons, and for good reason. In his book About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made, Ben Yagoda writes that the cartoon (drawn by Rose, with spinach line provided by E.B. White) “was picking up on something in the culture: it was a moment when the air reverberated with the sound of speech.” Yagoda notes that although “the cartoons led the way,” the magazine has always been filled with the sound of voices in “The Talk of the Town.” Naturalistic rendering of speech could also be found under the heading of such features as “Overheard,” which ran from 1927-1929 and included such contributors as the young writer John O’Hara.

Another New Yorker contributor whose work resounded with the sound of speech, Robert Benchley, received some kind words from the magazine on his latest book, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea or David Copperfield:

* * *

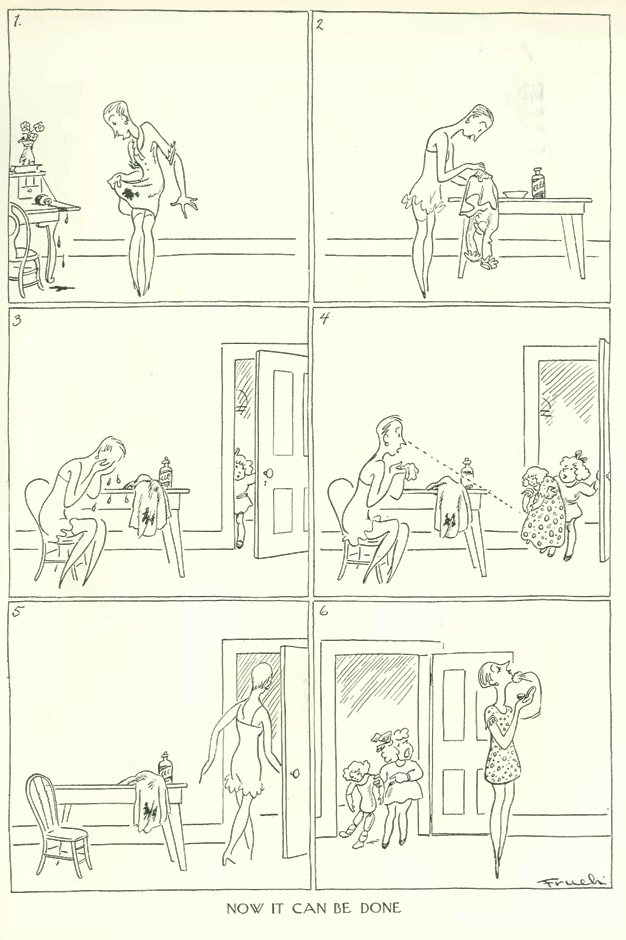

Appearing at the Civic Repertory Theatre (founded by actress Eva Le Gallienne in 1926) was Alla Nazimova and Eva herself in Anton Chekov’s last play, The Cherry Orchard. Al Frueh offered this sketch for the theatre review section.

* * *

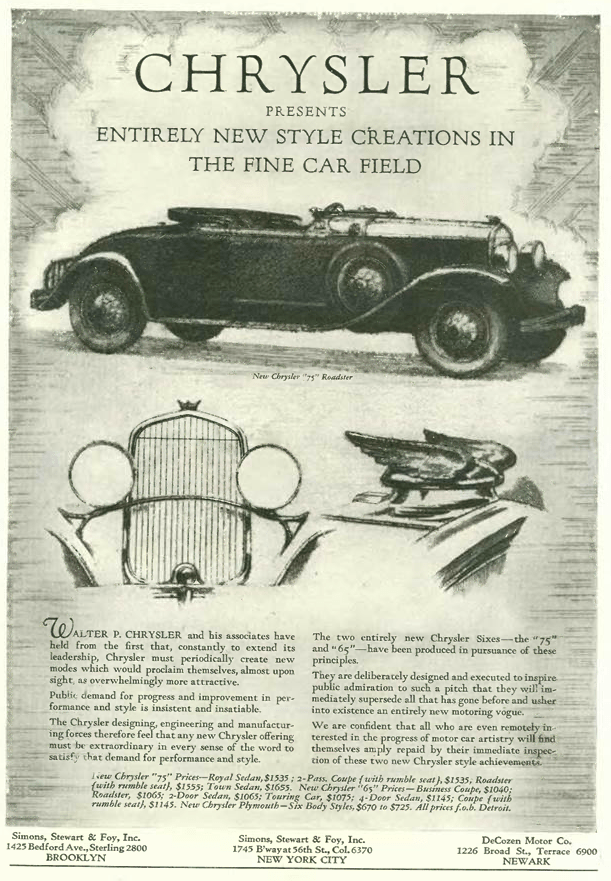

From Our Advertisers

Advertisements from the Dec. 8 issue offered this study in contrasts…a “modern” take on the holidays by Wanamaker’s, featuring the unfortunately titled “Psycho-Gifts for Christmas”…

…versus the staid offerings of Brooks Brothers on the following page…

* * *

On to the Dec. 15 issue, we find The New Yorker enjoying the debut of the Ziegfeld Follies latest revue…

…the show “Whoopee” at the New Amsterdam, featuring Eddie Cantor:

And lest you think audiences were flocking to only see Eddie Cantor…

* * *

On to less glamorous pursuits, The New Yorker also paid a visit to the new “Fish Wing” at the Museum of Natural History, as recounted in “Talk of the Town.” A brief excerpt:

From Our Advertisers…

…comes this house ad from The New Yorker itself, promoting its first-ever Album:

Chris Wheeler has gathered all of the albums at this site.

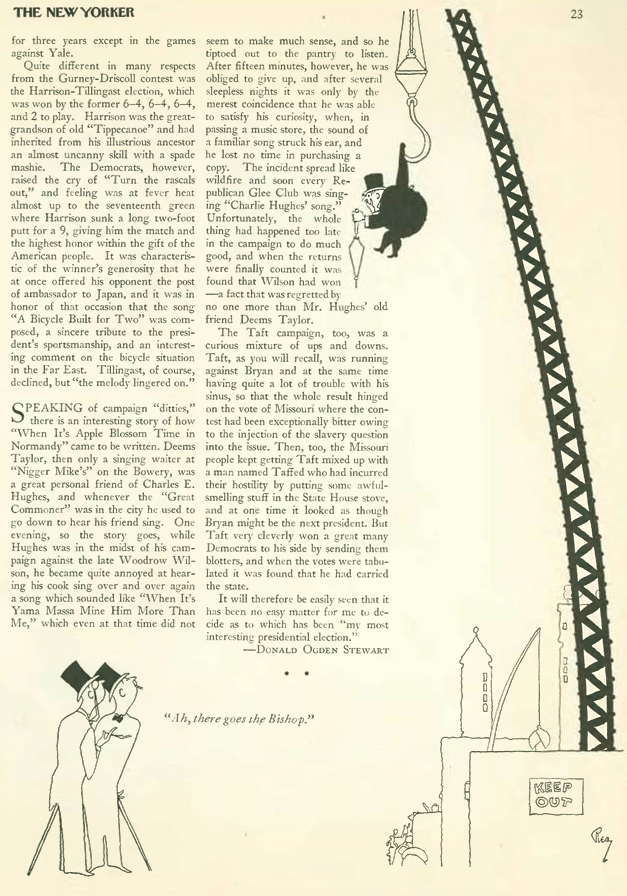

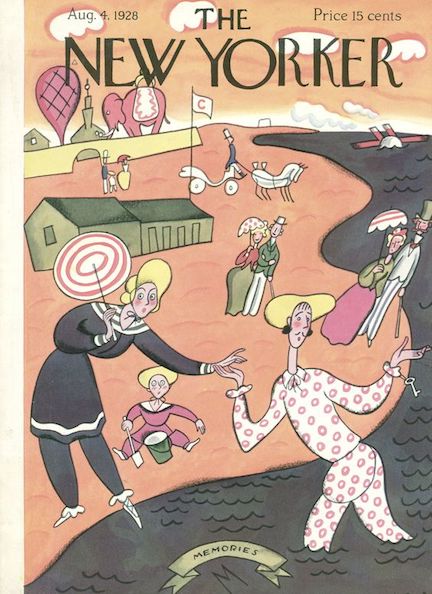

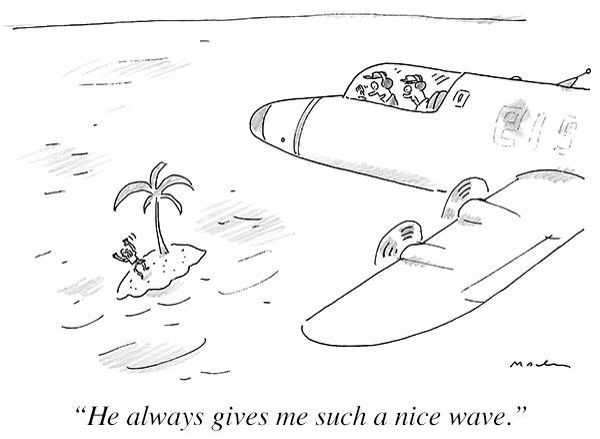

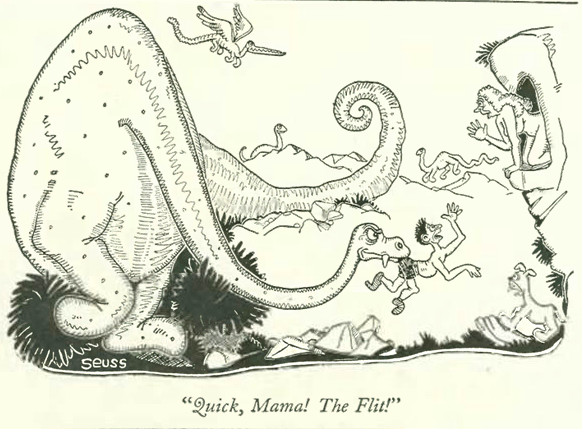

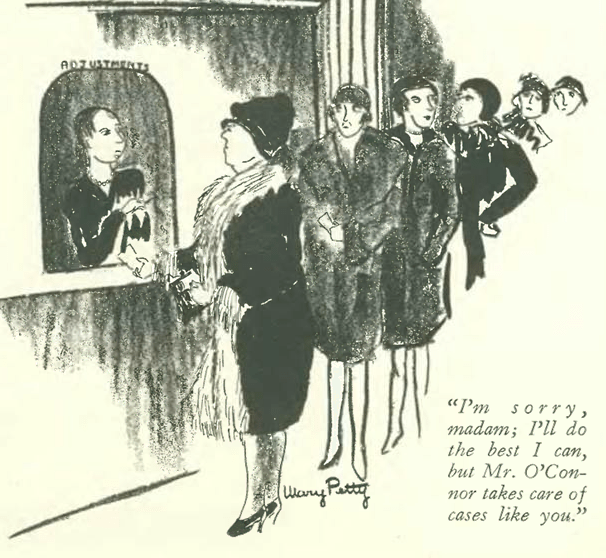

And finally, our cartoon, courtesy Peter Arno:

Next Time: Happy 1929!