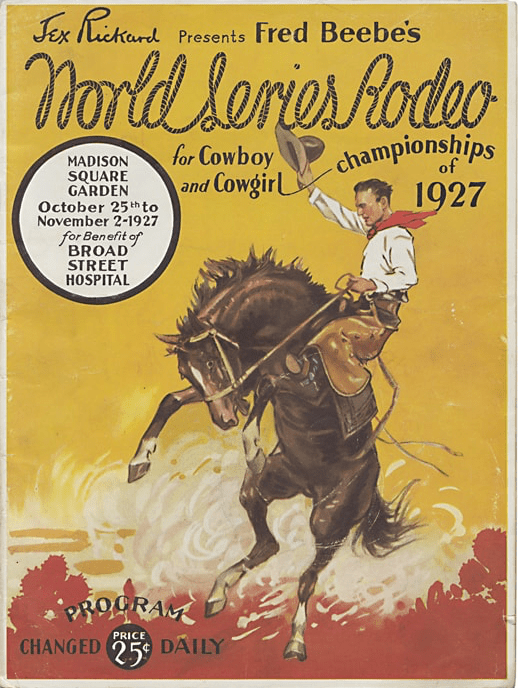

Gene Tunney was not your typical boxer. Holder of the heavyweight title from 1926 to 1928, he defeated his rival Jack Dempsey in 1926 and again in 1927 in the famous “Long Count Fight.” But Tunney was no Palooka—he preferred to be known as a cultured gentleman, and made a number of friends in the literary world including George Bernard Shaw, Ernest Hemingway and Thornton Wilder.

So when given the opportunity to say a few words, Tunney made the most of it, including at a dinner hosted by boxing and hockey promoter Tex Rickard to honor champions in various sports. The New Yorker’s E.B. White was there tell us about it:

While Tunney was doubtless composing his thoughts at the banquet table, baseball legend Babe Ruth was wishing he could be someplace else…

…like hanging out with his old buddy Jack Dempsey…

Instead, the Babe would have to listen to a surprise speech by Tunney, who sought to prove to those in attendance that he had brains to match his brawn. No doubt to the relief of many in attendance, New York City’s flamboyant mayor, Jimmy Walker, was able to return the proceedings to party mode.

* * *

The New Yorker writers found little to like about Hollywood, but Charlie Chaplin could always be counted on to knock out a humorous film. At least most of the time. Here is what “The Talk of the Town” had to say about his latest, The Circus:

* * *

Give ‘Em Dirty Laundry

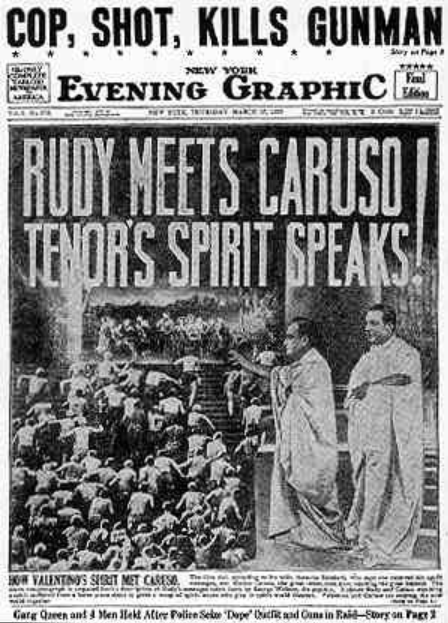

In these days of clickbait and other news designed to attract our prurient interest, we can look back 89 years a see that the tabloids were doing much of the same, particularly in Bernarr Macfadden’s New York Graphic, which was making the most of the final days of death row inmates Ruth Snyder and Judd Gray. “The Talk of the Town” (likely Robert Benchley) made this observation:

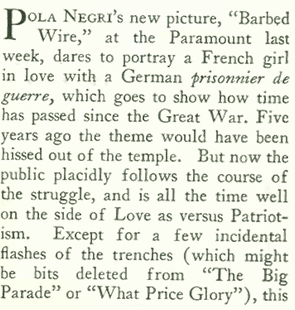

Former lovers Snyder and Gray were sentenced to death in 1927 for the premeditated murder of Snyder’s husband (they went to the electric chair at Sing Sing prison on Jan. 12, 1928). Newspapers across the country sensationalized their trial, but the Graphic went the extra step by paying large sums to celebrity correspondents, including evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, to write about the sordid case. Sister Aimee used her Graphic column to encourage young men to “want a wife like mother — not a Red Hot cutie.” Semple McPherson herself would later be accused of an affair, but then what else is new in the business of casting stones?

* * *

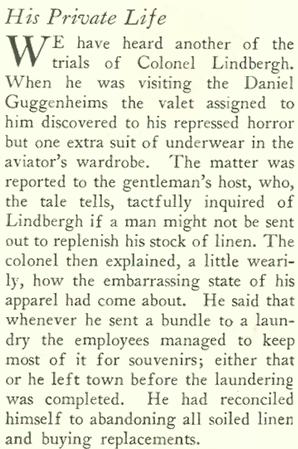

Even His Skivvies?

We can also look back 89 years and see that people were just as celebrity-crazed then as they are now. Charles Lindbergh could barely keep the clothes on his back while being pursued by adoring mobs, according to “The Talk of the Town”…

* * *

Kindred Spirits

Dorothy Parker wrote a vigorous, even impassioned defense of the late dancer Isadora Duncan in her column, “Reading and Writing.” Parker reviewed Duncan’s posthumously published autobiography, My Life, which she found “interesting and proudly moving” even if the book itself was “abominably written,” filled with passages of “idiotic naïveté” and “horrendously flowery verbiage.” In this “mess of prose” Parker also found passion, suffering and glamour—three words that Parker could have used to describe her own life.

Parker elaborated on the word “glamour,” which she thought had been cheapened in her day to something merely glittery and all surface. True glamour, wrote Parker, was that of Isadora Duncan, coming from her “great, torn, bewildered, foolhardy soul.” Parker concluded with this plea:

* * *

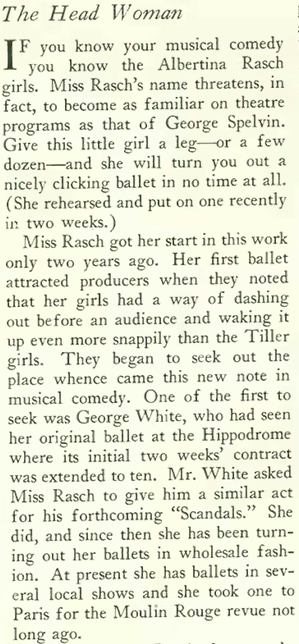

New Kid on the Block

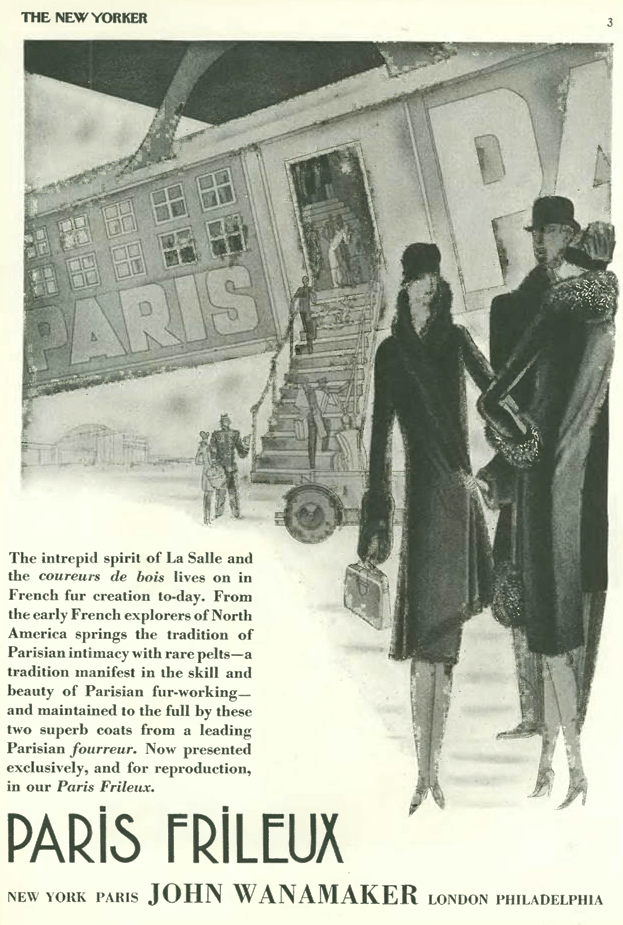

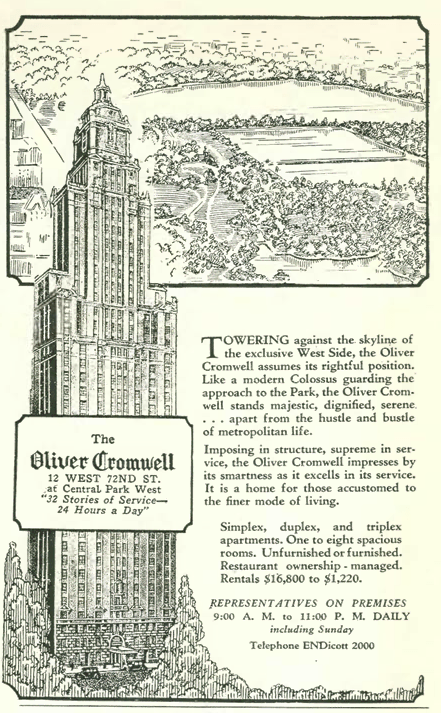

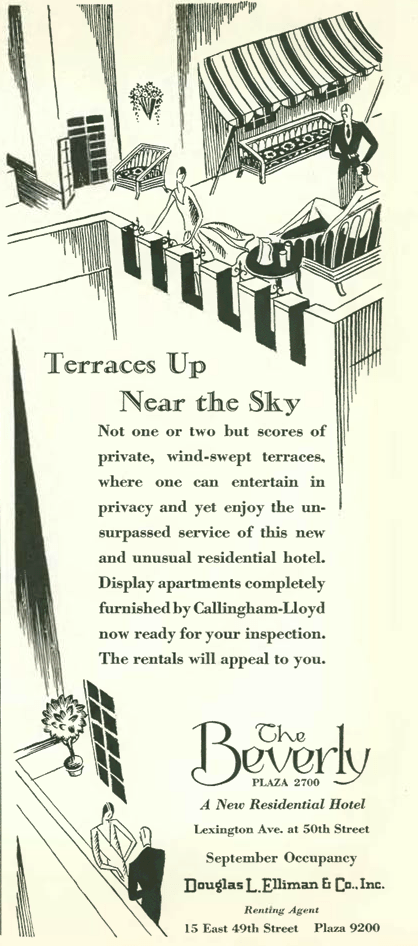

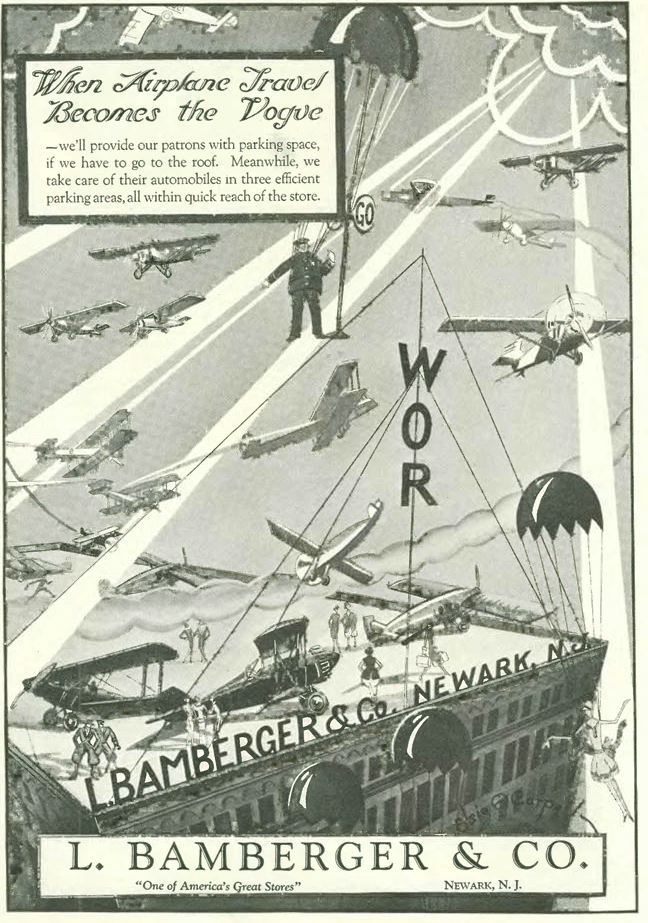

Yet another high-rise dwelling was available to Jazz Age New Yorkers—One Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village. One Fifth Avenue was an apartment with the word “hotel” attached to justify its 27-story height. To meet zoning requirements, the apartments had “pantries” instead of kitchens. But then again, your “servant” would fetch your dinner anyway…

Historical note: One Fifth Avenue marked a dramatic change in the character of Washington Square, one of the most prestigious residential neighborhoods of early New York City. A previous occupant of the One Fifth Avenue site was the brownstone mansion of William Butler Duncan. In addition to One Fifth Avenue, the residences at 3, 5, and 7 Fifth Avenue were also demolished to make way for the new art deco “apartment hotel.”

* * *

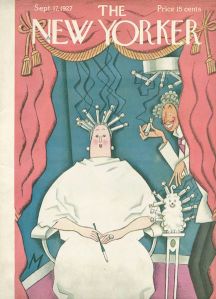

To close, a two-page spread by Helen Hokinson exploring one woman’s challenge with the “flapper bob” (sorry about the crease in the scan–that is how it is reproduced in the online archive). Click the image to enlarge.

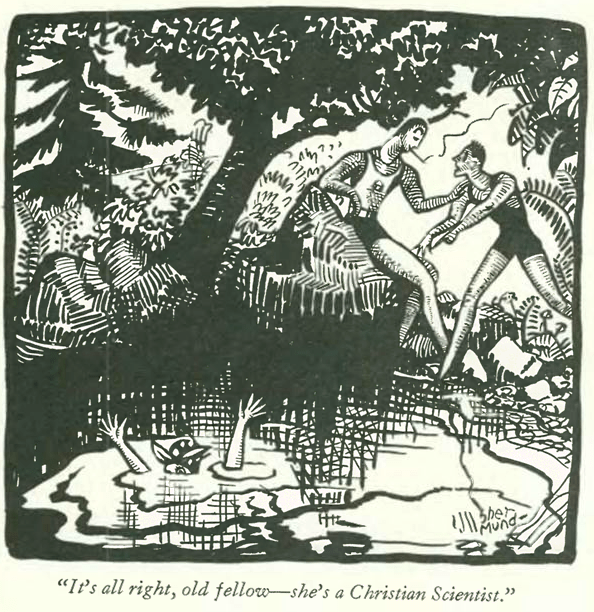

And a bit of fun on the streetcar, courtesy of cartoonist Leonard Dove…

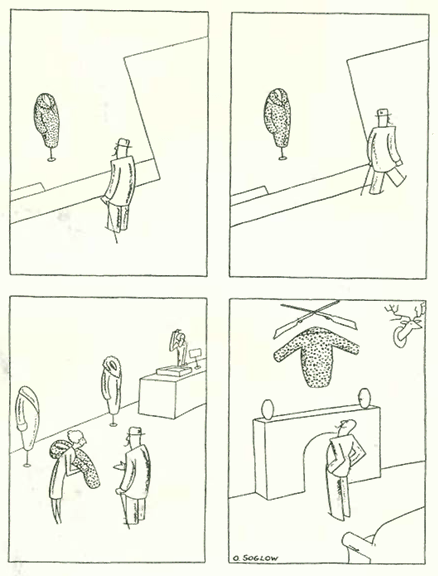

…and a confession, from Otto Soglow…

Next Time: Machine Age Bromance…