My last entry featured cartoonist Bud Fisher, inventor of the comic “strip” (Mutt & Jeff) and the subject of The New Yorker’s Nov. 26, 1927 “Profile.” It was something of a surprise, then, to open the next issue, Dec. 3, and find literary critic Dorothy Parker offering her observations on the funny papers, including Sidney Smith’s comic strip, The Gumps.

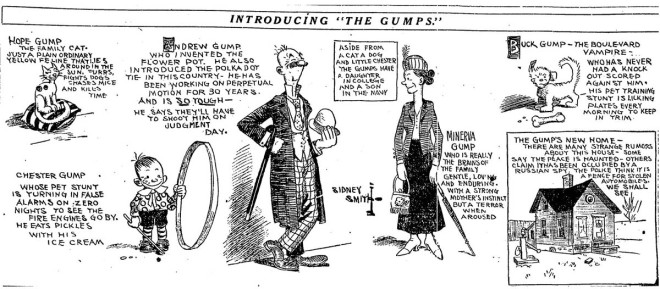

Before we get to Dorothy Parker, let’s have a look at The Gumps, created by Sidney Smith in 1917. Although that strip had plenty of slapstick, it was wordier than Mutt & Jeff and somewhat more realistic (Smith was the first cartoonist to kill off a regular character, in 1929–it caused a national outcry). An example of the strip from around 1920:

Like Bud Fisher, Smith would become wealthy from the merchandising of Gump toys, games, songs, food products, etc…

The Gumps were also featured in nearly 50 animated shorts, and between 1923 and 1928 Universal produced dozens of two-reel comedies starring Joe Murphy (one of the original Keystone Cops) as Andy Gump, Fay Tincher as Min and Jack Morgan as Chester (two-reelers were usually comedies, about 20 minutes in length). The director of these short films, Norman Taurog, would go on to become the youngest director to win an Academy Award (Skippy 1931). He would also direct such films as Boy’s Town (1938) and nine Elvis Presley movies from 1960 to 1968.

His comic strip barely five years old, in 1922 Smith famously signed a 10-year, one million-dollar contract. In 1935 he would sign an even more lucrative contract, but on his way home from the signing he would die in a car accident.

In her column, “Reading and Writing,” Dorothy Parker (writing under the pen name “Constant Reader”) lamented the fact that the comic strips were abandoning simple, light horseplay in favor of “melodramas.” Apparently even Andy Gump wasn’t exempt:

Parker also bemoaned the likes of Little Orphan Annie and the gang from Gasoline Alley, where everyday hijinks were replaced by melodrama:

Parker suffered throughout her life from depression, and no doubt turned to the funnies for respite. However, she wrote that she hadn’t “seen a Pow or a Bam in an egg’s age,” and sadly concluded that melodrama was what the readers wanted.

When Minerva Was a Car

The New Yorker’s Nicholas Trott visited the Automobile Salon at the Hotel Commodore and noted that the latest trend favored an automobile’s “ruggedness” over its “prettiness.” Given the condition of roads in the 1920s, that probably wasn’t a bad thing…

In the early days of the auto industry there were thousands of different manufacturers that eventually went broke or merged with other companies. Trott’s article mentioned new offerings from Chrysler, Mercedes, and Cadillac as well as from such makes as Erskine, Sterns-Knight, Minerva, Holbrook Franklin, Stutz, and Brewster.

In “The Talk of the Town,” however, the editors wrote about another car with a far less colorful name: The Ford Model A. After 18 years of the ubiquitous black Model T, Ford buyers were ready for something different…

New Yorker editors cautioned, however, that buyers of the Model A should “not expect too much” from a car aimed at more modest pocketbooks. In a little more than a year Ford would sell one million of the things, and by the summer of 1929, more than two million.

When Model A production ended in early 1932, nearly five million of the cars had been produced.

German Atrocities?

It’s seemed a bit of an “about face” for New Yorker architecture critic George S. Chappell to write of the “horrific style of modern Germany” after previously writing admiringly of the Bauhaus movement and “International Style” promulgated by Le Corbusier. Chappell’s column “The Sky Line” included this subhead, “German Atrocities Neatly Escaped.” In a few years “German Atrocities” would refer to something very different…

Another monstrous building of note in Chappell’s column was the “huge” Equitable Trust Building at 15 Broad Street…

To save the best for last, Chappell also wrote of Cass Gilbert’s landmark New York Life Building, rising on the site of the old Madison Square Garden…

* * *

She Nearly Made It

Morris Markey wrote about the exploits of pilot and actress Ruth Elder (1902–1977) in his “Reporter at Large” column. Known as the “Miss America of Aviation,” on Oct. 11, 1927, Elder and her co-pilot, George Haldeman, took off from New York in her attempt to become the first woman to make a transatlantic crossing to Paris. Mechanical problems in their airplane (a Stinson Detroiter dubbed American Girl) caused them to ditch into the ocean 350 miles northeast of the Azores. Fortunately they were rescued by a Dutch oil tanker in the vicinity.

Although they were unable to duplicate Charles Lindbergh’s feat, Elder and Haldeman nevertheless established a new over-water endurance flight record of 2,623 miles–the longest flight ever made by a woman. They were honored with a ticker-tape parade upon their return to New York. Despite her derring-do, Elder suggested that she longed for a simpler, more domestic life…

Whether or not she found the simple life it is hard to say. She married six times, perhaps looking for the right “old stuff” and not quite finding it.

* * *

And finally, this ad from the Dec. 3 issue featuring the art of New Yorker contributor John Held Jr…

…and this cartoon by Otto Soglow, depicting how one toff bags his “trophy”…

Next Time: The Perfect Gift for 1927…

One thought on “More Funny Business”