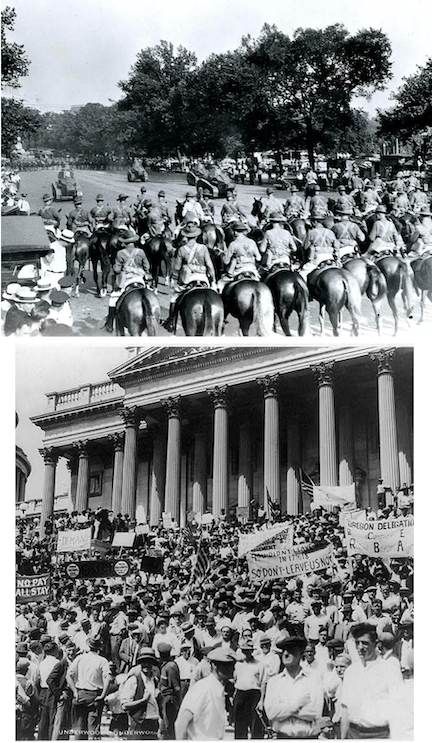

From the 1930s until the 1950s, New York City was the one place where American communists almost became a mass movement.

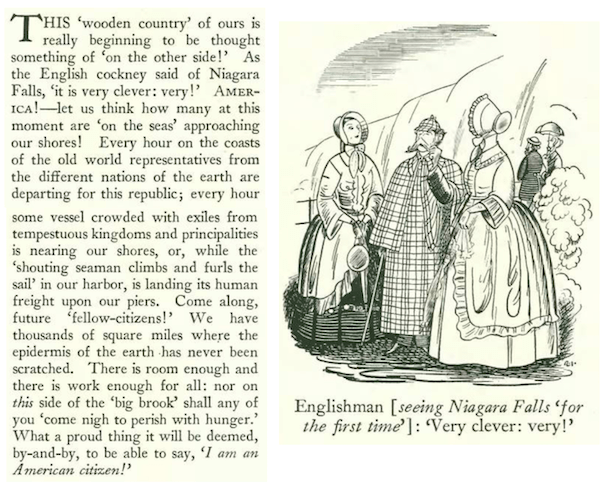

Writing in The New York Times opinion section (Oct. 20, 2017), Maurice Isserman observed how in those days New York party members “could live in a milieu where co-workers, neighbors and the family dentist were fellow Communists; they bought life insurance policies from party-controlled fraternal organizations; they could even spend their evenings out in night clubs run by Communist sympathizers…” we skip to the Sept . 17 issue in which journalist Matthew Josephson penned a report on the movement for the “Reporter at Large” column titled “The Red House”…excerpts:

According to Isserman (a professor of history at Hamilton College), in 1938 the Communist Party of America counted 38,000 members in New York State alone, most of them living in New York City. A Communist candidate for president of the board of aldermen received nearly 100,000 votes that same year, with party members playing a central role in promoting trade unions.

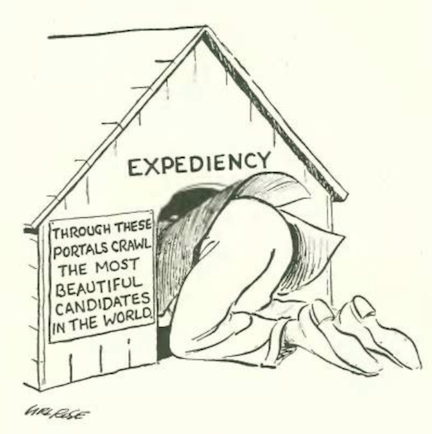

Josephson commented on the candidates appearing on the Communist ticket in the 1932 U.S. presidential elections, finding James W. Ford to be “much more intellectual” than his running mate:

Josephson concluded his article with observation of a party protest event, and one unmoved police officer…

Postscript: The Cold War in the 1950s and a renewed Red Scare spelled the end of the party’s heyday, as did Nikita Khrushchev’s 1956 speech that denounced the murderous legacy of his predecessor, Josef Stalin.

* * *

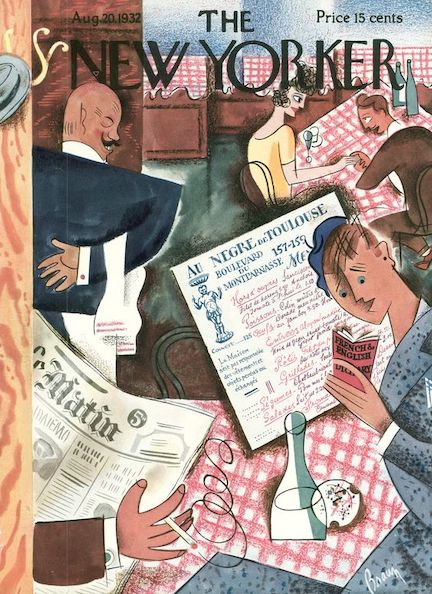

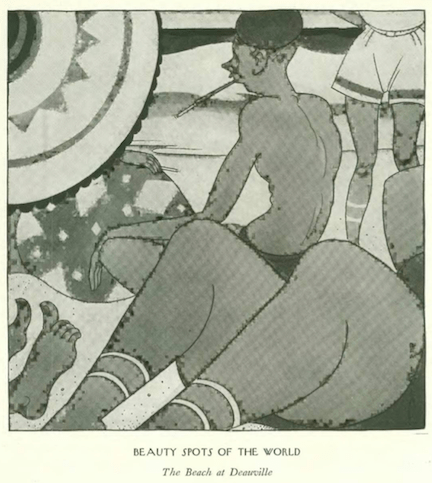

Très Chic

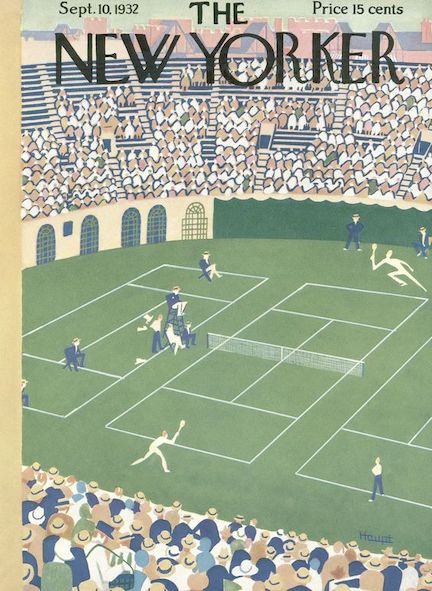

For those with means, the idea of living in the same building with other non-family humans seemed unseemly, but in 1870 Rutherford Stuyvesant hired Richard Morris Hunt to design a five-story apartment building for middle-class folks that had a decidedly Parisian flair. The Sept. 10 “Talk of the Town” explained:

According to Ephemeral New York, the apartments were initially dubbed a “folly,” but the building’s 16 apartments and four artists’ studios—located near chic Union Square—were quickly snapped up, creating a demand for more apartments. The building remained fully occupied until it was demolished in 1958. According to another favorite blog—Daytonian in Manhattan—demolition of Morris Hunt’s soundly built, sound-proof building was a challenge.

* * *

Some Characters

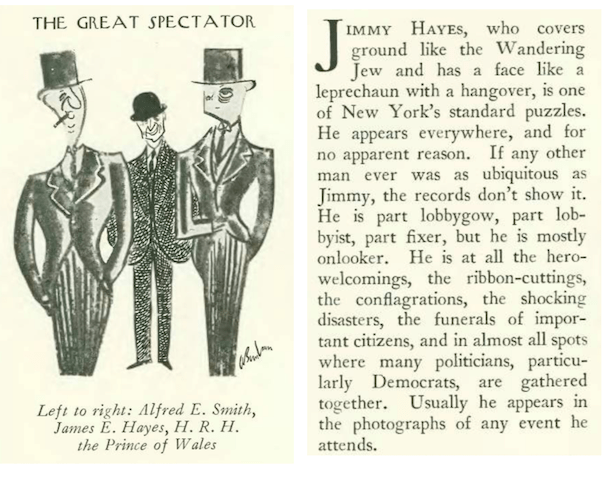

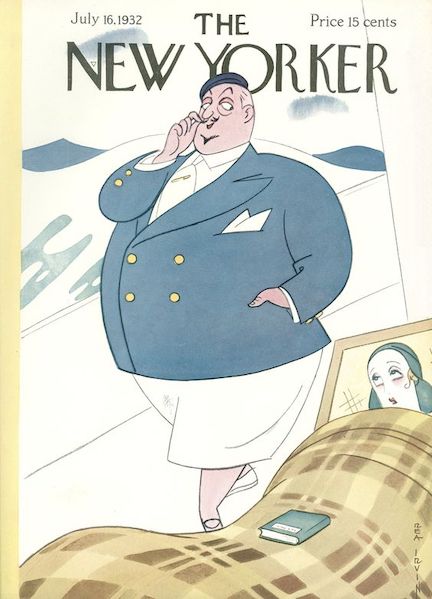

I include this brief snippet of the Sept. 10 “Profile” for the jolly illustration by Abe Birnbaum of Al Smith, Jimmy Hayes and the Prince of Wales…

* * *

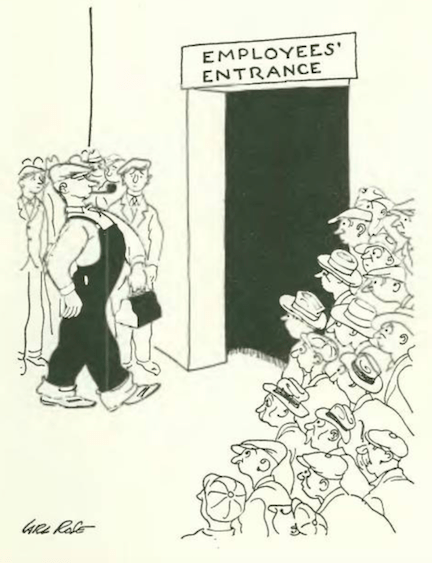

Down In Front

E.B. White was always on the lookout for the newfangled in the world of transportation, but this latest development by the Long Island Railroad was not a breath of fresh air…

White also looked in on the latest news from the world of genetics—with hindsight we can read about these developments with a degree of alarm, since Hitler was months away from taking control of Germany…

* * *

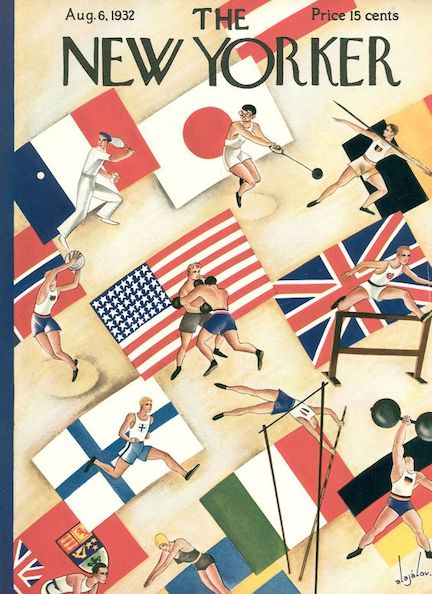

Showing His Colors

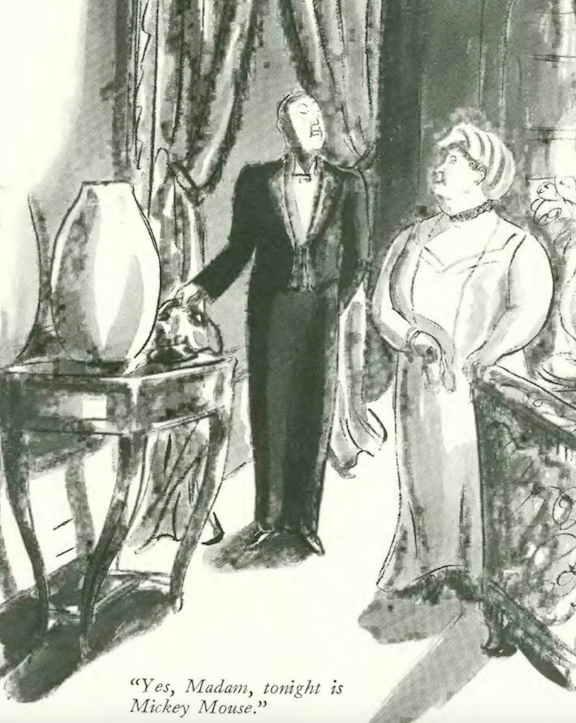

On to lighter matters, critic John Mosher enjoyed an eight-minute animated Walt Disney short, Flowers and Trees—the first commercially released film made in full-color Technicolor…

…Mosher also took in light entertainment of the live-action variety with Marion Davies and Billie Dove providing some amusement in Blonde of the Follies, although the picture could have used a bit more Jimmy Durante, billed as a co-star but making an all-too-brief appearance…

* * *

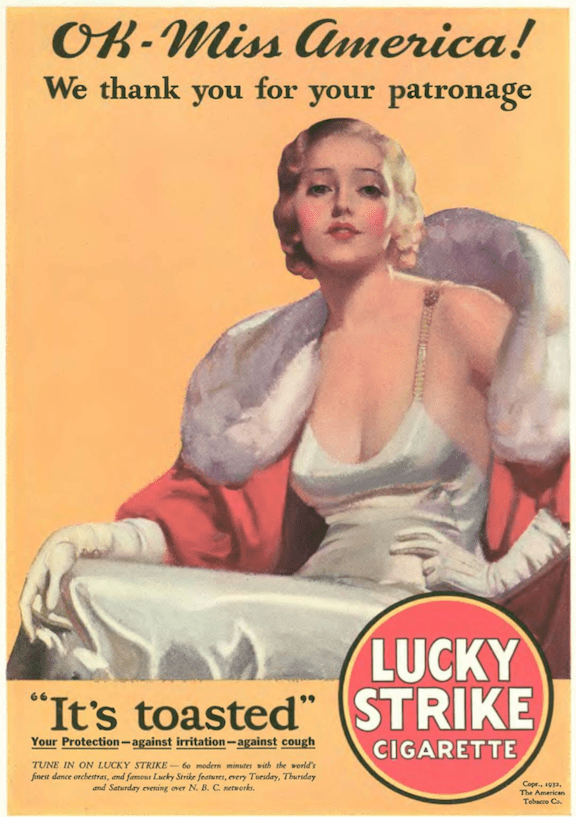

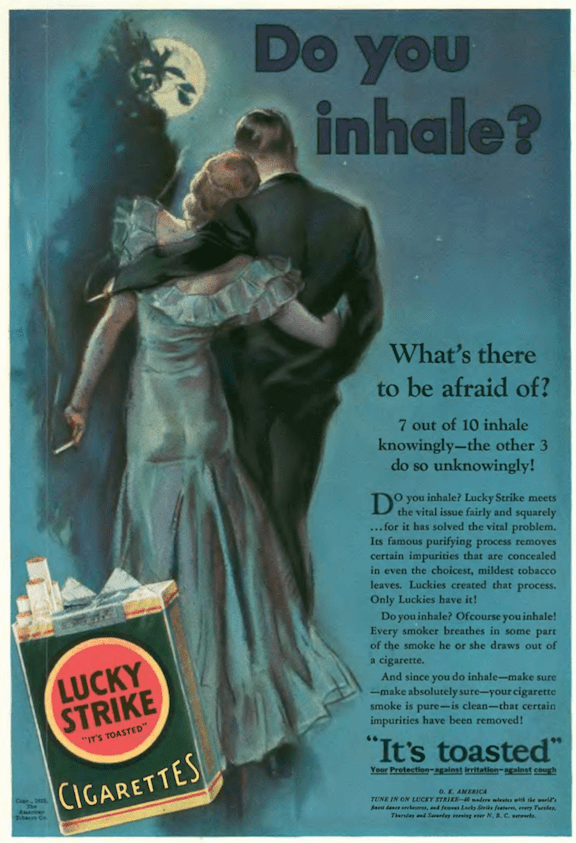

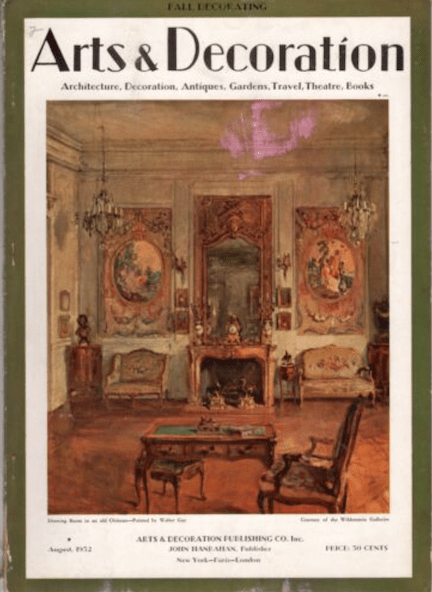

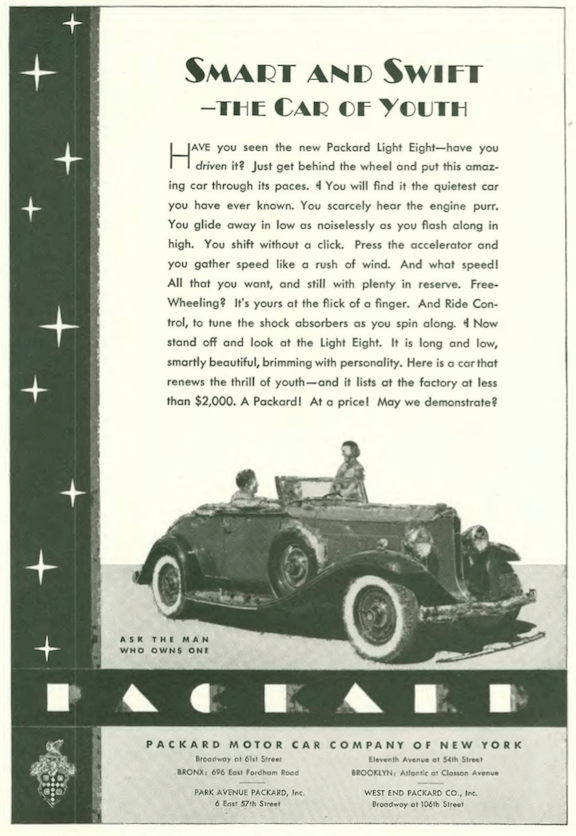

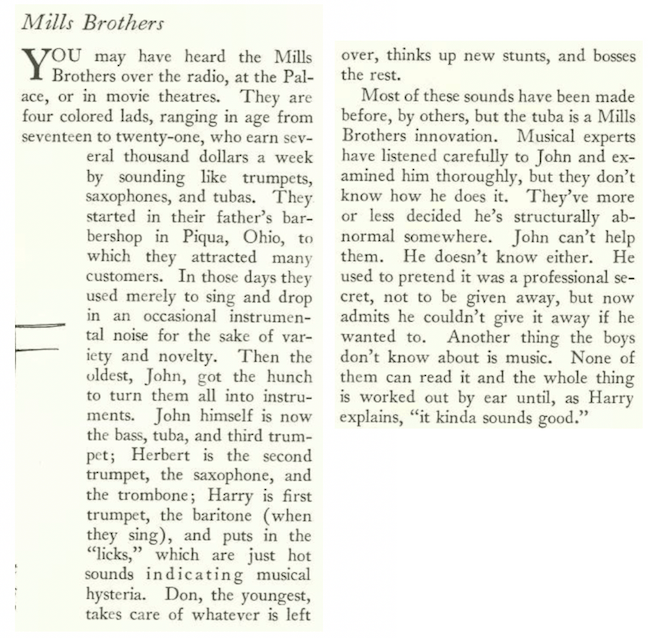

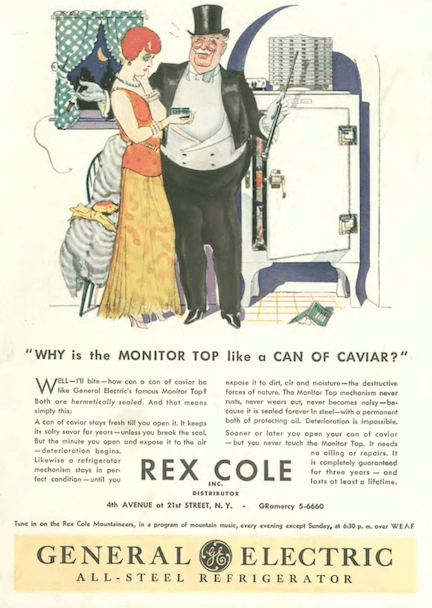

From Our Advertisers

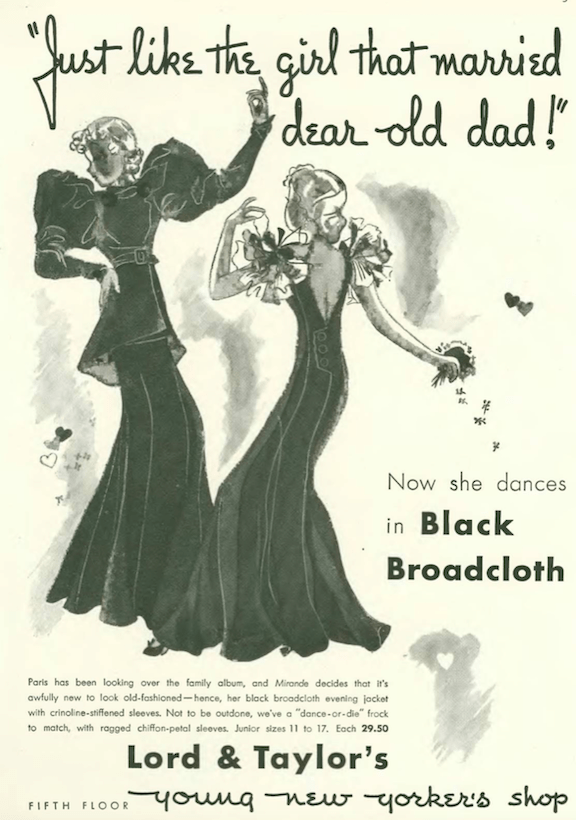

Lord & Taylor announced the return of Edwardian styles as the latest in fashion among the younger set, once again proving what goes around comes around, ad infinitum…

…except when it comes to “college styles”…I don’t see this look returning to our campuses anytime soon…

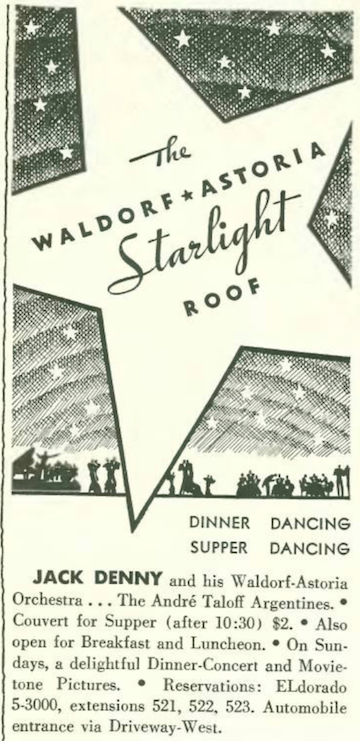

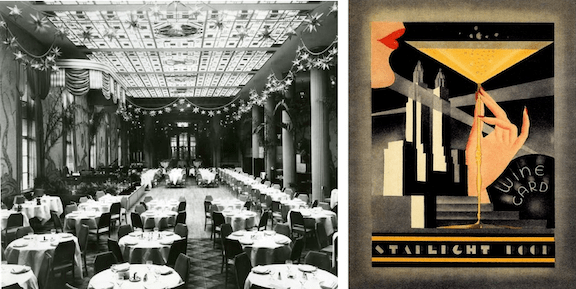

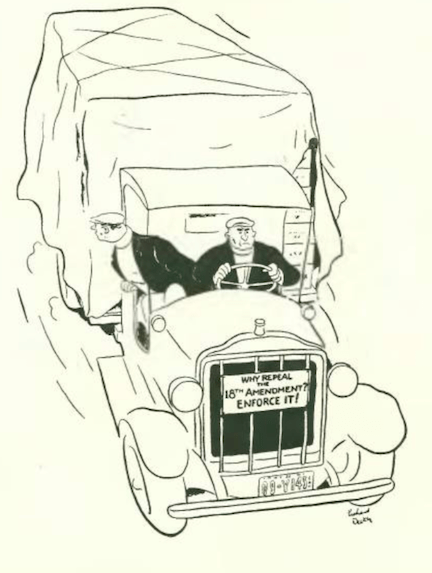

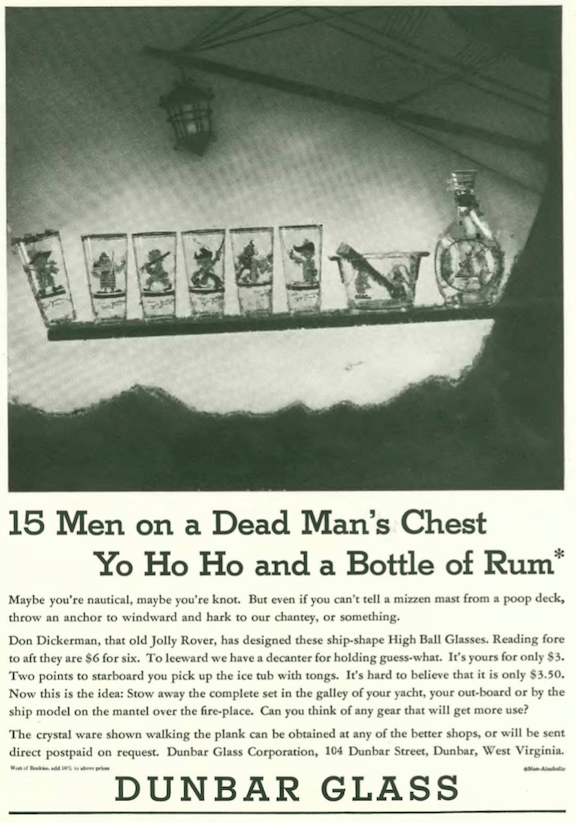

…the end of Prohibition was still a year away, but at least in New York it was all but over…I like the Hoffman ad and its winking line “with or without”…

…as a courtesy to readers (and to fill a blank space) the New Yorker “presented” a full page of signature ads touting a variety of specialty schools and courses…the Carson Long Military Academy (right hand column) closed in 2018 after 182 years of “making men”…

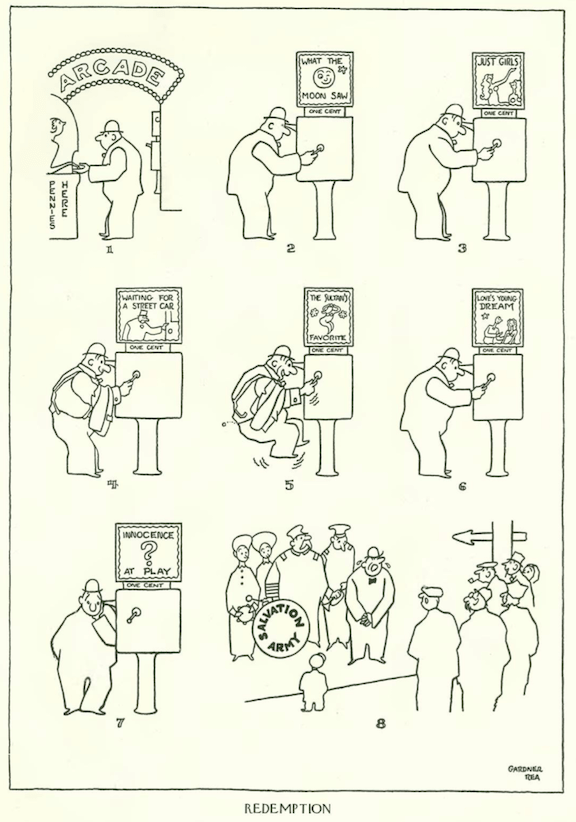

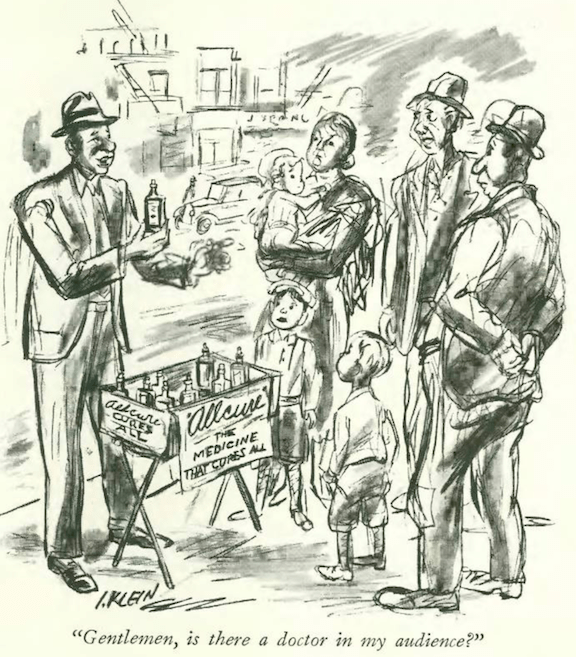

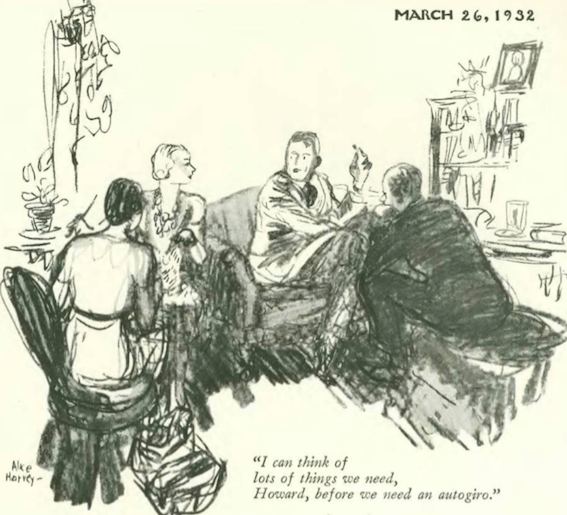

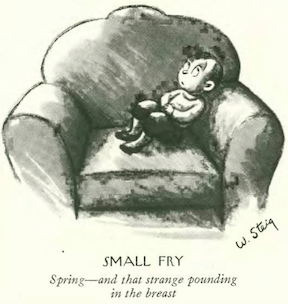

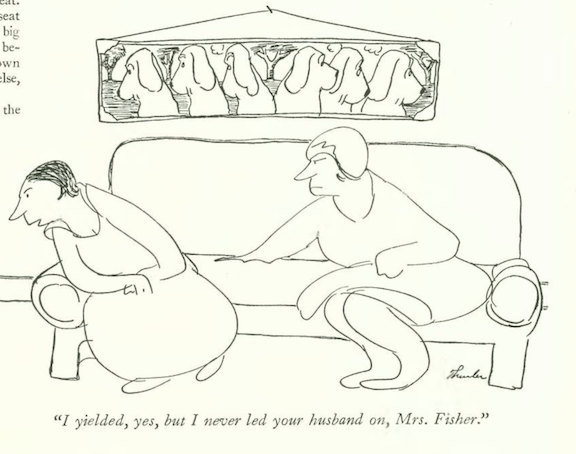

…on to our cartoonists and illustrators, we begin with this Isadore Klein illustration in the opening pages…

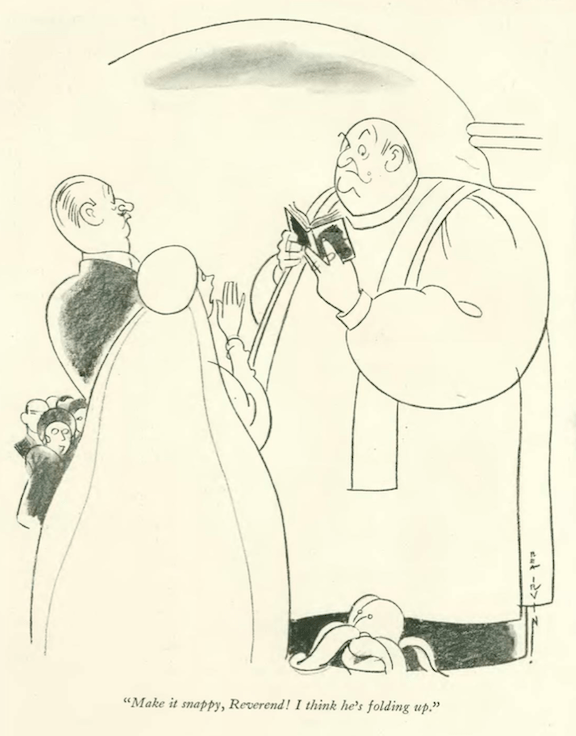

…Rea Irvin gave us a nervous moment at the altar…

…and Richard Decker showed us one groovy grandma…

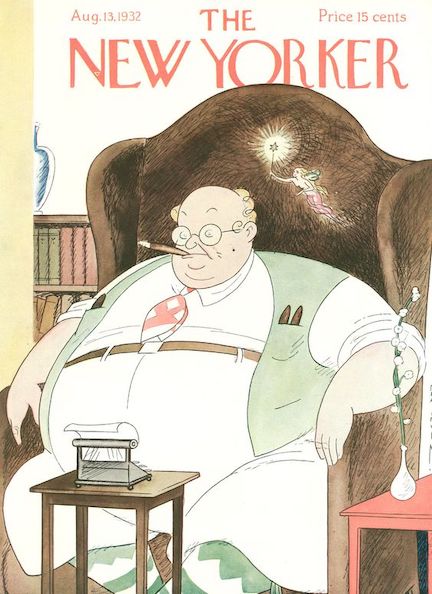

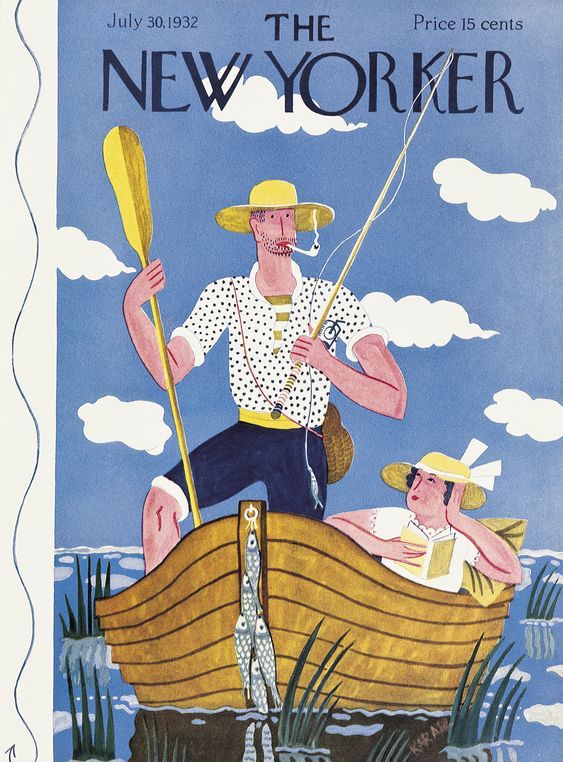

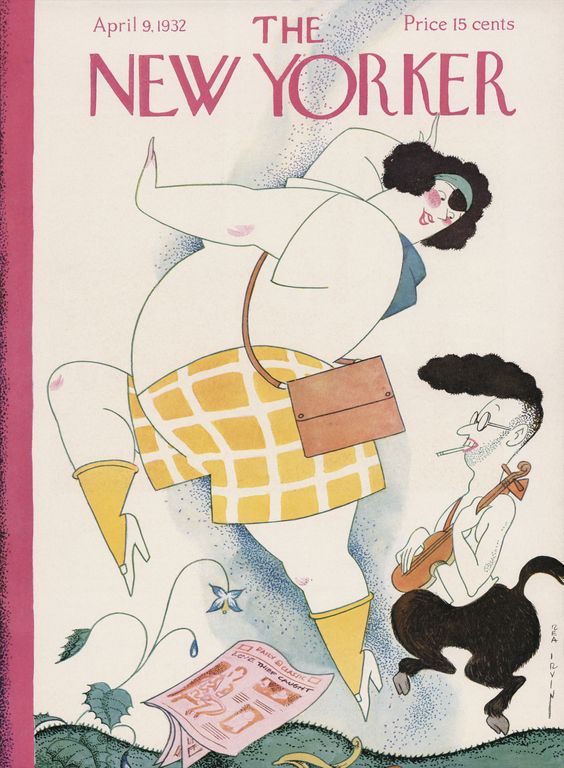

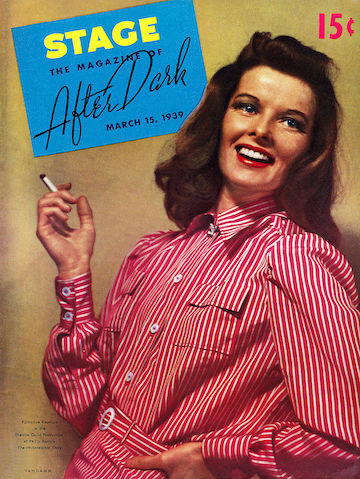

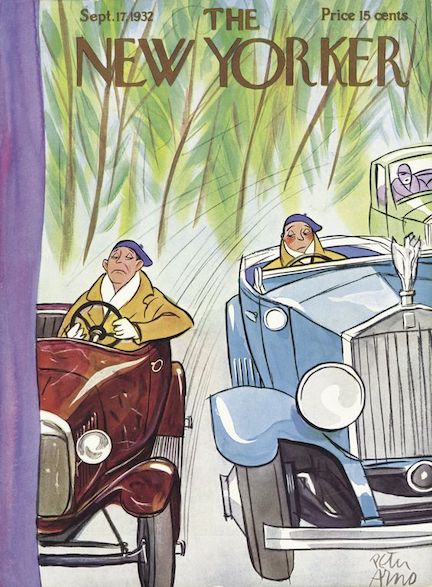

…on to the Sept. 17 issue (which we dipped into at the start)…and what a way to begin with this terrific cover by Peter Arno…

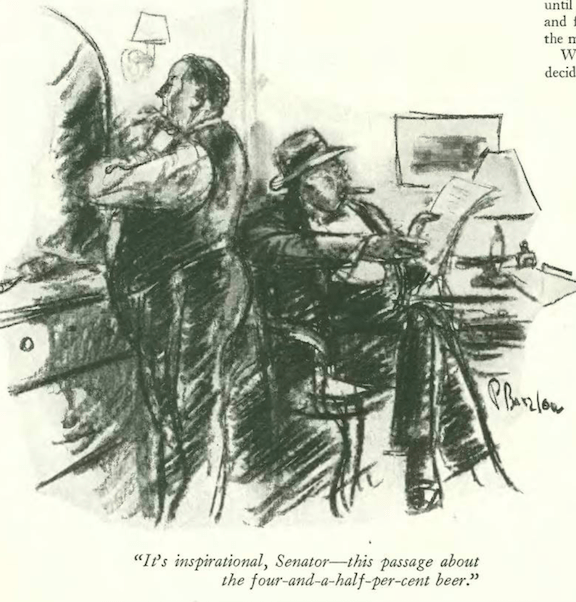

…in his “Notes and Comments,” E.B. White offered some parting words for the departing (and scandal-ridden) Mayor Jimmy Walker…

…and Howard Brubaker added his two cents regarding Walker and his replacement, Joseph McKee, who served as acting mayor until Dec. 31, 1932…

* * *

Heady Role

The British actor Claude Rains earned his acting chops on the London Stage before coming to Broadway, where in 1932 he appeared in The Man Who Reclaimed His Head — E.B. White was subbing for regular critic Robert Benchley, and concluded that Rains should have used his own head before agreeing to appear in such silly stuff…

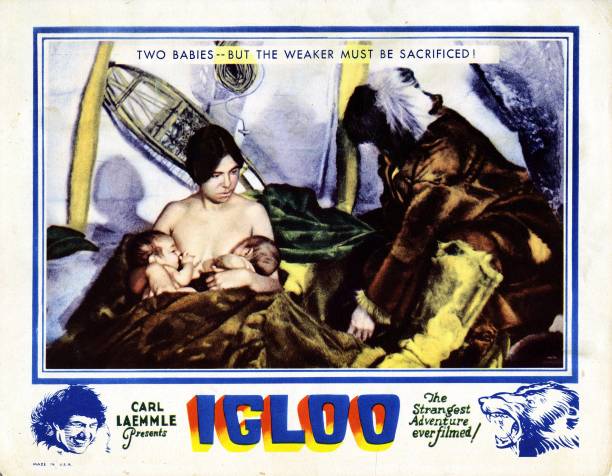

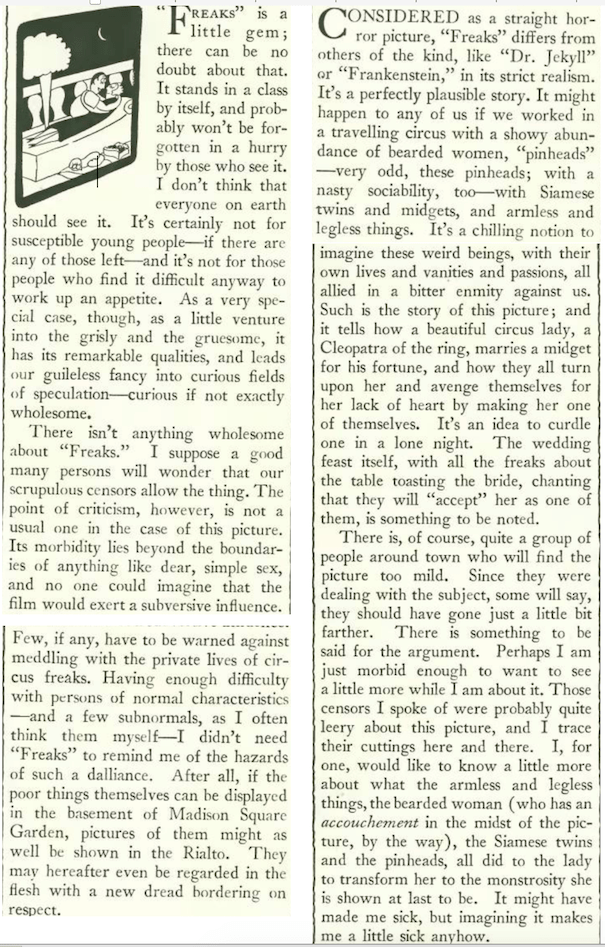

…and speaking of the silver screen, we turn to critic John Mosher and his review of the 1931 German film

Mädchen in Uniform was almost banned in the U.S., but Eleanor Roosevelt spoke highly of the film, resulting in a limited US release (albeit a heavily-cut version) in 1932–33.

* * *

From Our Advertisers

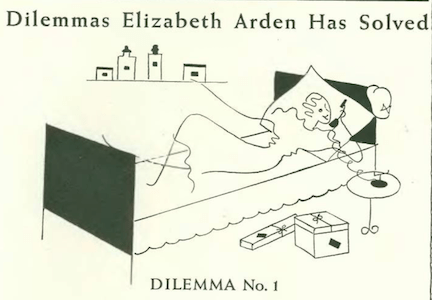

I’m featuring this detail from an Elizabeth Arden ad because the illustrator’s style is so distinct…if someone knows the identity of the artist, please let us know (on other drawings I’ve seen a signature that looks like “coco”)…

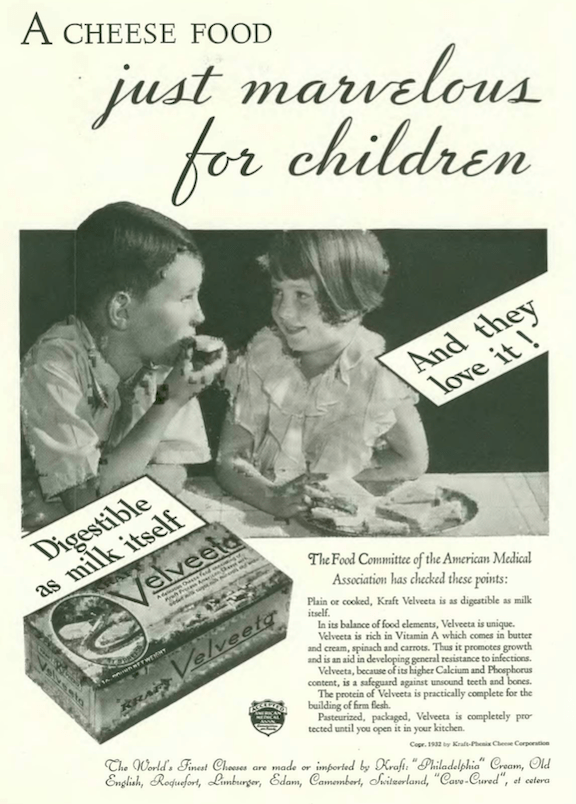

…invented in 1918, this “cheese food” made from milk, water, whey, milk protein concentrate, milkfat, whey protein concentrate and sodium phosphates—among other things—was acquired by Kraft in 1927 and marketed in the 1930s as a nutritious health food…I have to say I haven’t seen any Velveeta ads in The New Yorker as of late…

…”Pier 57, North River!” barks the successful-looking man to the admiring cabby who’s thinking “lucky dog!”…

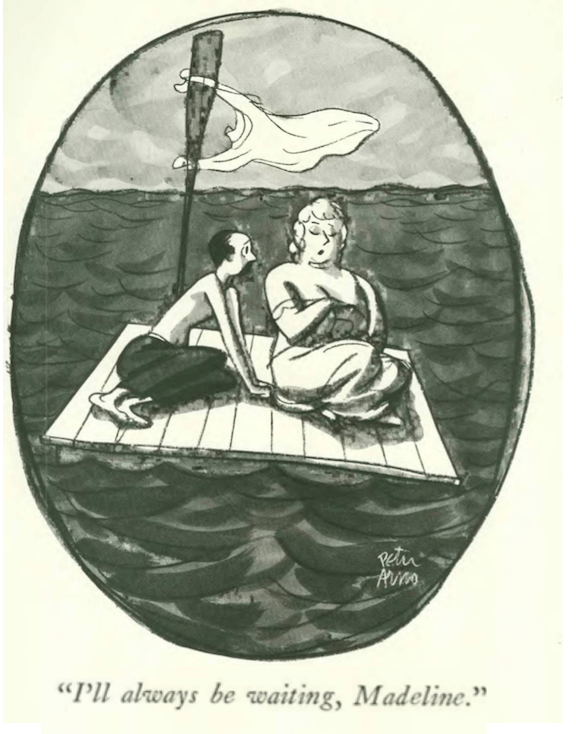

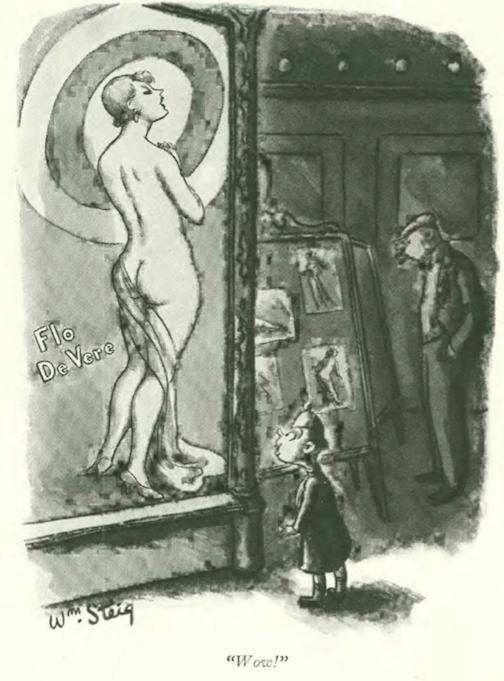

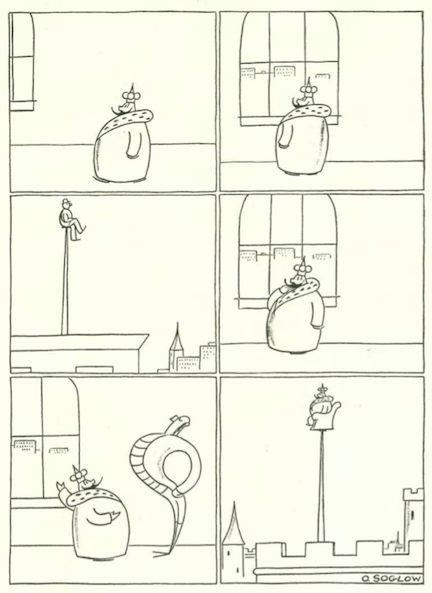

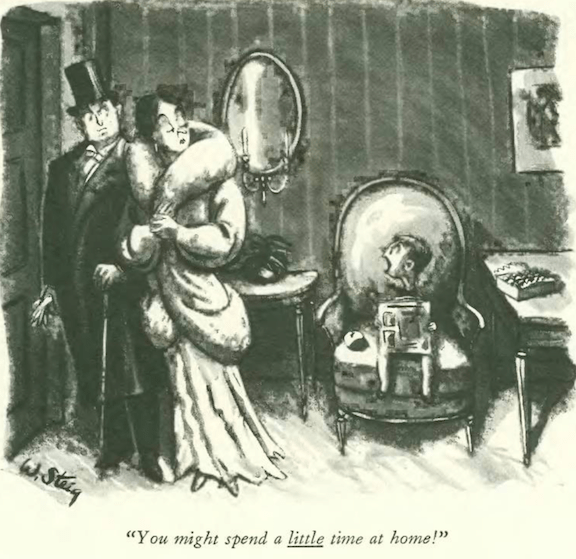

…on the other hand, Peter Arno (kicking off our Sept. 17 cartoons) gave us a Milquetoast who wasn’t getting anywhere near the French Line, or First Base…

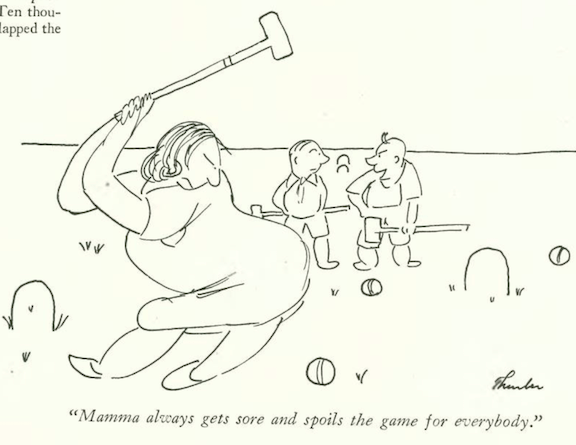

…and speaking of the mild-mannered, James Thurber offered up this fellow…

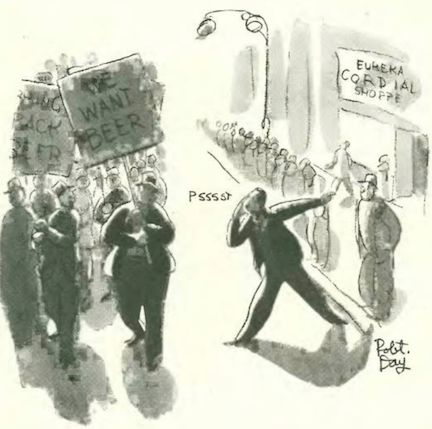

…Helen Hokinson’s “girls” were perhaps wondering if their driver was among the Commies at Union Square…

…John Held Jr. entertained with another “naughty” Victorian portrait…

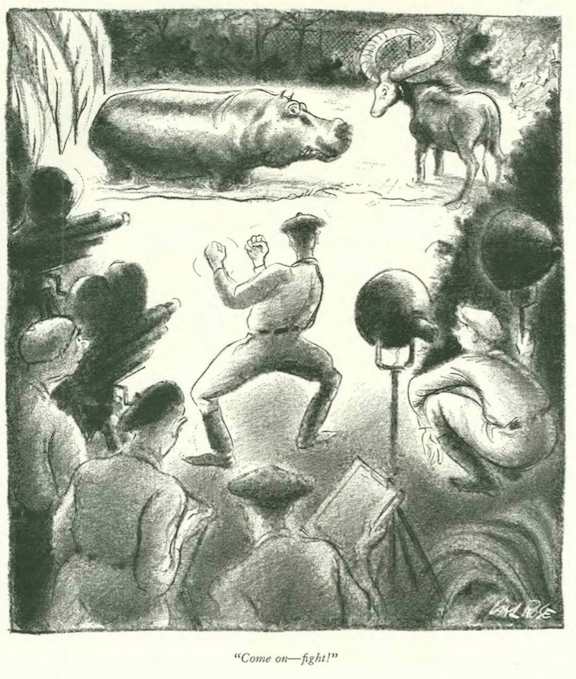

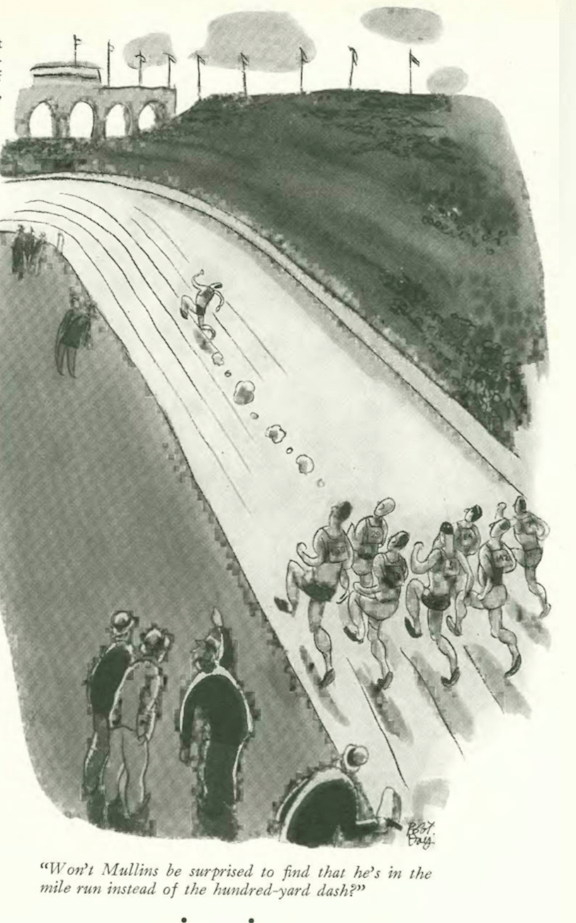

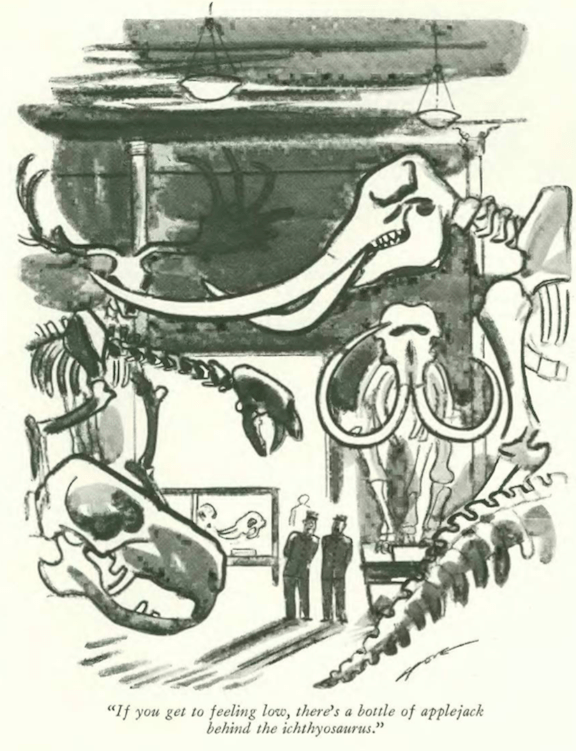

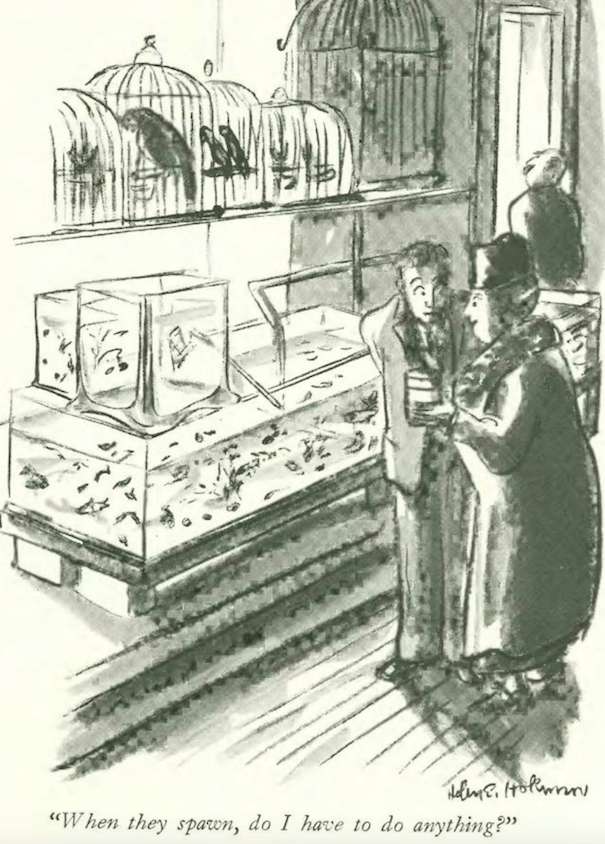

…Robert Day, and wish unfulfilled at the zoo…

…and we close with Richard Decker, and trouble in the Yankee dugout…

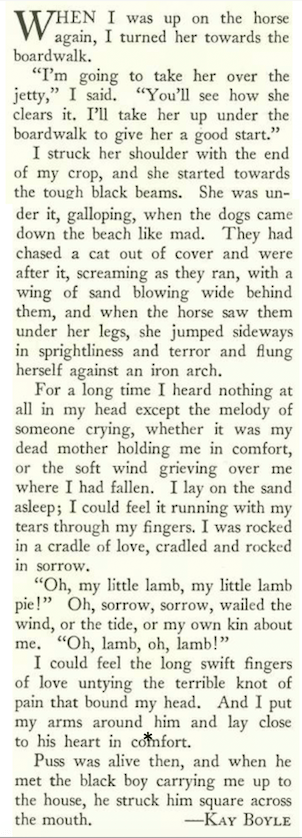

Next Time: A Picture’s Worth…