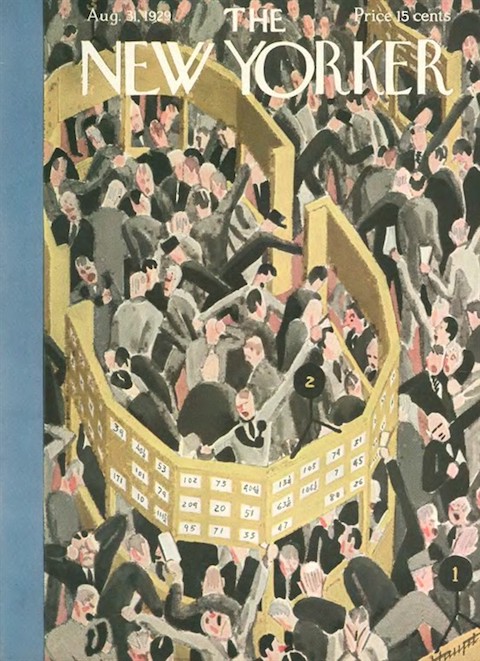

When Charles Lindbergh gunned his Wright Whirlwind engine on Roosevelt Field and took to the skies on his historic flight, he sparked such an interest in flying that just two years later that very same field was hosting huge weekend crowds that came to marvel at the airborne wonders of a new age.

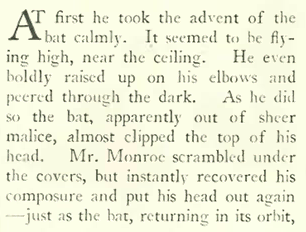

Writing for “The Talk of the Town,” James Thurber was on hand to take in the spectacle, noting how the announcer sold air-mindedness to the mob “in great clamorous phrases and resonant assurances.” Among those taking their first flight was a “Mr. Galleger, aged 101.” Thurber also observed:

Although there were thrills galore up in the sky, Thurber seemed equally impressed by the spectacle on the ground…

One of the big attractions was Texaco Oil’s Spokane Sun God, which traveled around the country to demonstrate the art of mid-air refueling. Note in the excerpt below (second paragraph) how the Sun God’s pilot communicated with his ground crew: He tossed some notes—tied to a heavy piece of lead(!)—out of the airplane’s window. It nearly landed in a crowd of onlookers…

* * *

Falling Short

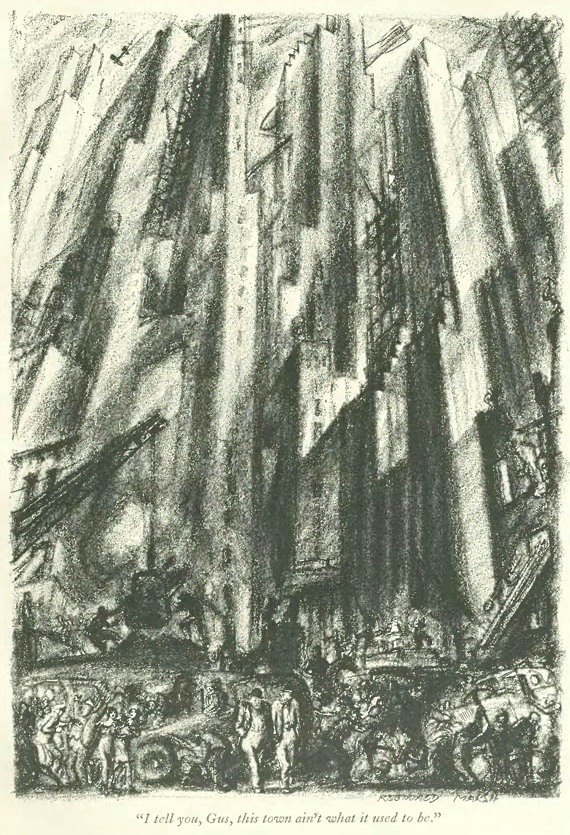

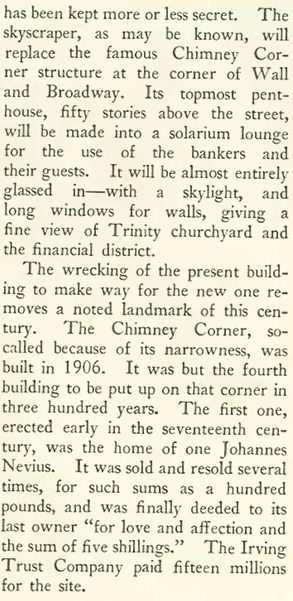

As I noted in a previous post (The Last Summer), the race to build the tallest building was erroneously reported by The New Yorker as a man against himself (namely, architect William Van Allen). In the Aug. 31 issue, the magazine’s “Talk of the Town” corrected the error, and added another curious note about another plan to build an “airplane lighthouse” taller than the Eiffel Tower…

As noted above, Col. Edward Howland Robinson Green (son of the notorious miser Hetty Green) wanted to build a thousand-foot tower on his estate in Massachusetts. Here is what he settled for instead:

* * *

When Trains Fly

Cashing in on the enthusiasm over aviation, the City of New York promoted its elevated train system as an “Air Line.” According to “Talk”…

Click on the video below to take a ride on the “L”. Most of the 1929 footage begins at 4:47…

* * *

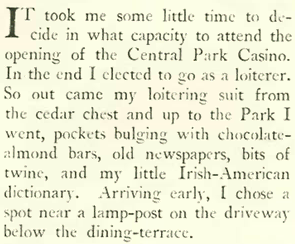

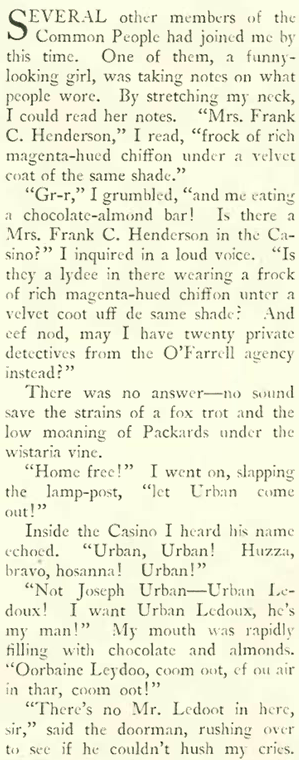

Haw Haw

One more “Talk” item: a self-referential piece in which The New Yorker pondered its “mission” as a humor magazine…

* * *

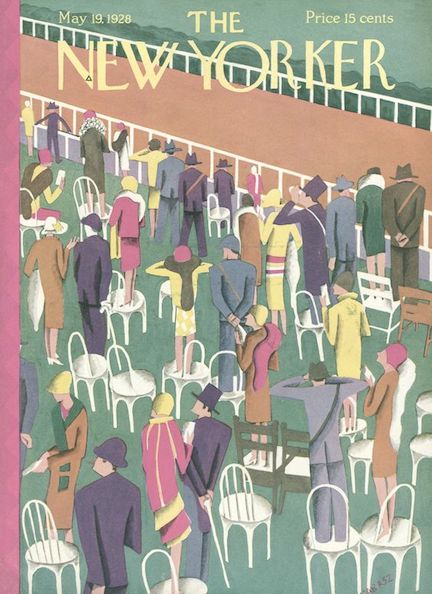

Audax Minor

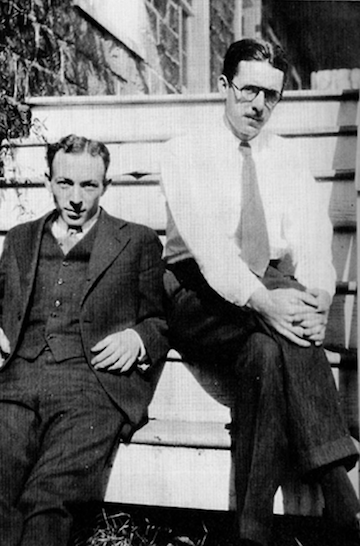

For more than five decades, George Francis Trafford Ryall (1887-1979) wrote the horse racing column for the New Yorker under the pseudonym Audax Minor. He published his first column on July 10, 1926, and his last on Dec. 18, 1978. He was the writer of longest record at the magazine when he died at age 92 in 1979 (52 years, a record that has been shattered by the nearly 98-year-old Roger Angell, who has published in the New Yorker from 1944 to 2018).

According to Ryall’s obituary in the New York Times, he adopted the nom de plume Audax Minor in a nod to Arthur F. B. Portman, who wrote about racing in England under the name of Audax Major. Ryall’s writing was so entertaining that many of his readers had never even been to a racetrack. According to Brendan Gill in his book, Here at the New Yorker, “(Ryall’s) world is a romantic fiction and they (the readers) are grateful when they learn that, with his green tweeds, his binoculars hung smartly athwart his chest, and his jaunty stride, Ryall resembles a character out of some sunny Edwardian novel.” An excerpt of his column from the Aug. 31 issue, with illustrations by Johan Bull:

* * *

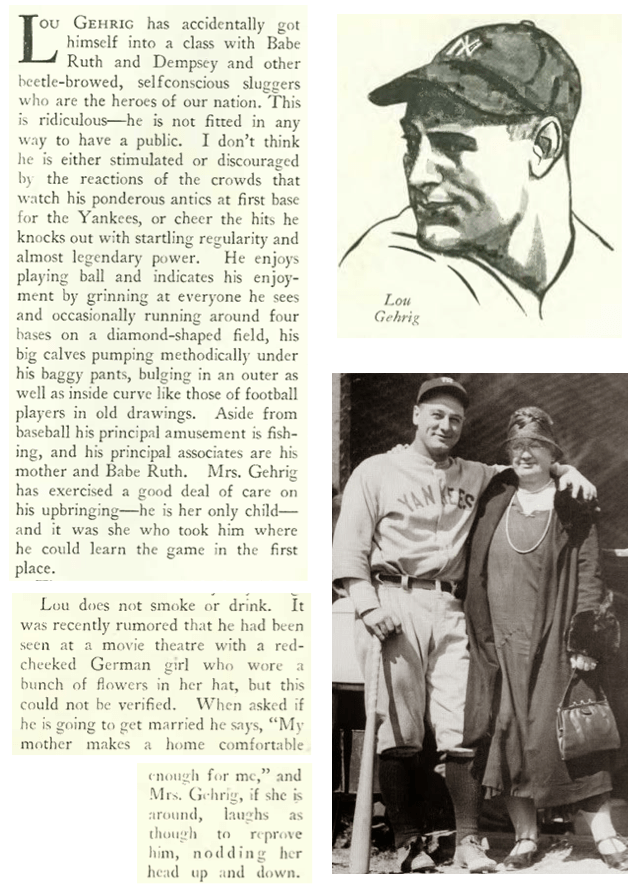

Shut Out

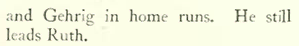

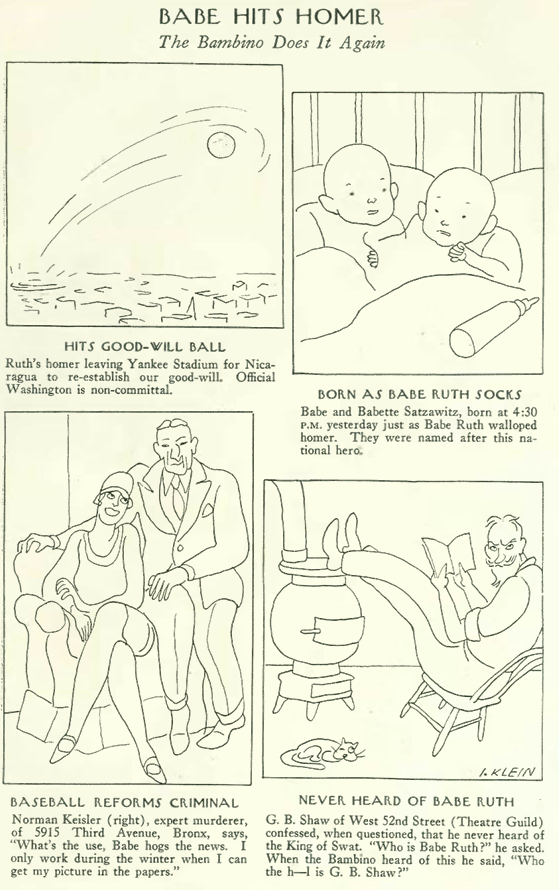

As I’ve noted before, the New Yorker covered nearly every imaginable sport except baseball. Here is a rare mention of the game in Howard Brubaker’s “Of All Things” column:

The Cubs would win the NL pennant, but they would fall to the Philadelphia Athletics in the 1929 World Series.

Rough and Ready

When Fiorello La Guardia challenged incumbent Jimmy Walker for New York City mayor in 1929, the city’s voters were presented with two colorful candidates who could not have been more different in their styles. Walker, a product of Tammany Hall, was a svelte dandy with a taste for the refined, whereas the reform-minded La Guardia was often coarse and unkempt. If they had anything in common, it was their dislike of Prohibition. La Guardia was featured in the Aug. 31 profile, written by Henry F. Pringle. Some excerpts:

* * *

Praise for the King

The New Yorker’s film critic John Mosher found most of Hollywood’s output to be pedestrian, but occasionally he saw a bright spot, including King Vidor’s latest production, Hallelujah:

As for another film, Paramount’s The Sophomore, Mosher probably felt a bit obligated to say something nice, since it was a derived from a story by humorist Corey Ford, an early contributor to The New Yorker and part of the Algonquin Round Table orbit:

* * *

A Bright Interval

The New Yorker gave a brief but approving mention of Nancy Hoyt’s latest book, Bright Intervals, in its book review section…

Hoyt was a member of a socially prominent but deeply troubled family that included her recently deceased sister, the poet and writer Elinor Wylie (I wrote about the Hoyt family in my post Generation of Vipers). Characters in Hoyt’s novels often resembled the women in her family.

* * *

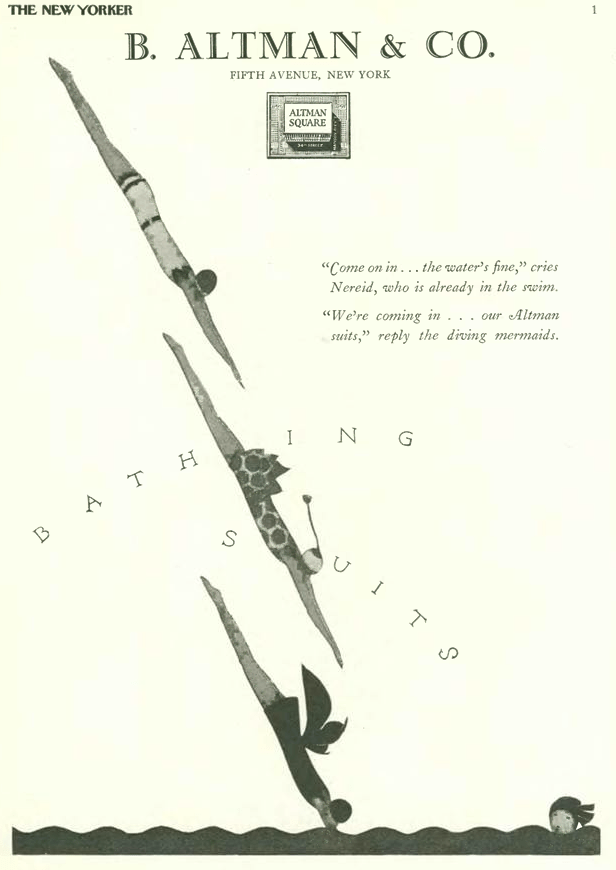

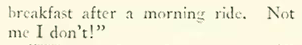

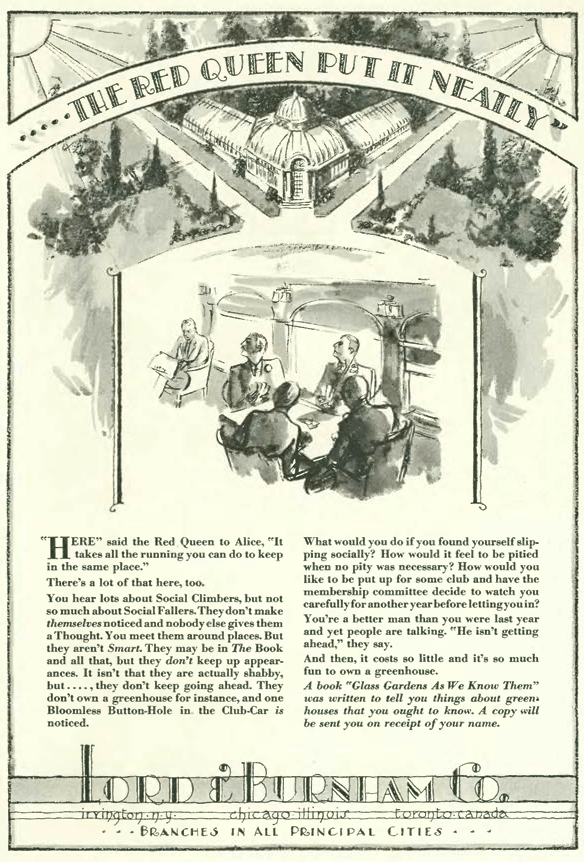

From Our Advertisers

It was back to college time, and Macy’s had a thrifty new fall lineup ready for the “Junior Deb”…

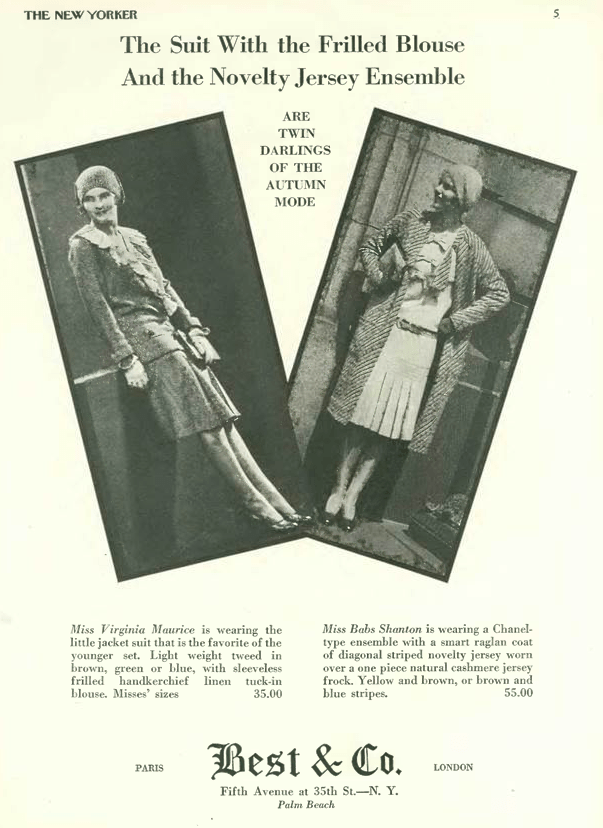

…and on the less thrifty side, Best & Company offered these new looks for fall…

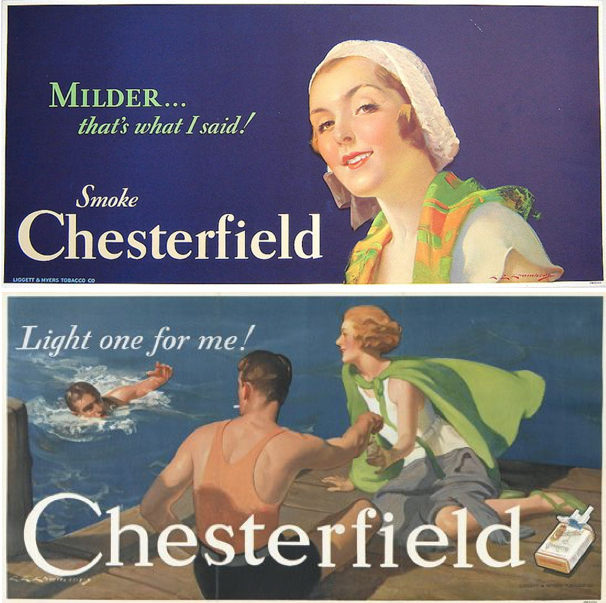

…note in the above ad that the first model is Virginia Maurice, the very same model we encountered in a recent post (The Last Summer) posing for Chesterfield cigarettes…

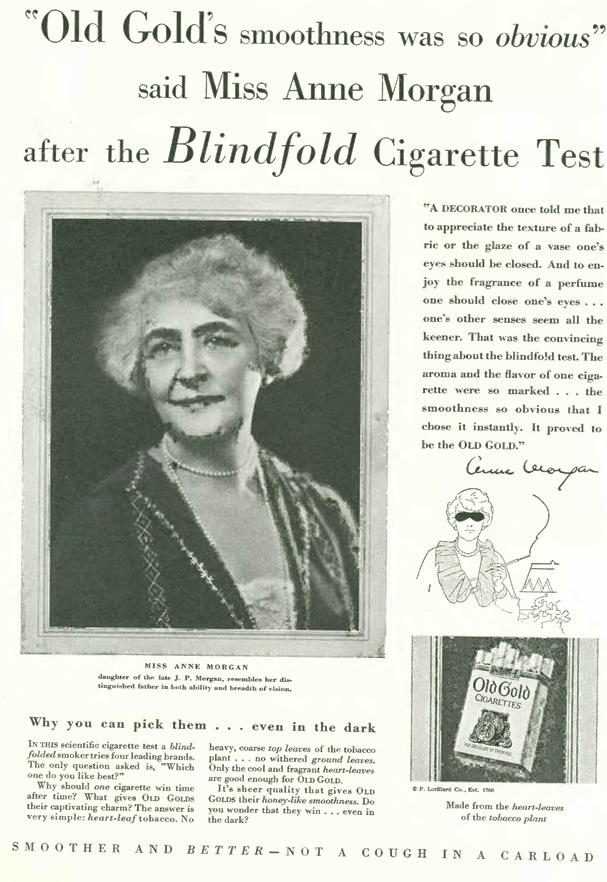

…the other model in the Best & Company ad, Babs Shanton, also wasn’t averse to taking money from the tobacco companies…

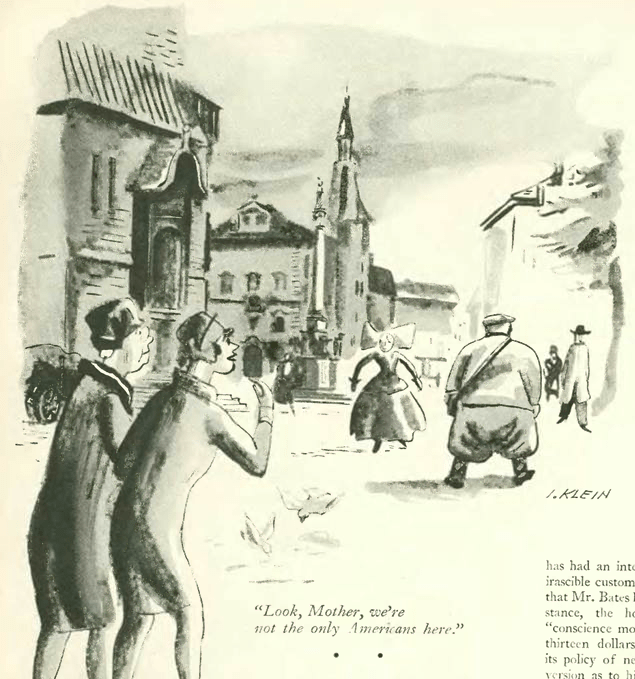

…the makers of Studebakers tried to add sex appeal in this ad for their President Roadster. The artist was obviously challenged to work all of the necessary elements into the picture—car, swimming pool, diving board—not to mention the block of superfluous text where the steps to this impossibly long diving board should have been located…

…and sex not only sold cars…its also sold printing services…

…instead of sex, the promoters of Tudor City chose strangulation to get their pitch across, equating a man’s daily train commute to death at the gallows (“Danny Deevers” refers to a character in a Rudyard Kipling poem who is hanged for murder)…

…the gawkers at Roosevelt Field weren’t the only folks with their heads in the clouds…an ad for Flit insecticide by Dr. Seuss…

…this ad for Raleigh cigarettes, which appeared on the back cover of the Aug. 31 issue, assumed that folks were so familiar with their mascot that no further explanation was needed…

…here is a 1929 ad from House Beautiful that featured the same mascot with the Van Dyke beard…both ads were rendered by French illustrator Guy Arnoux…

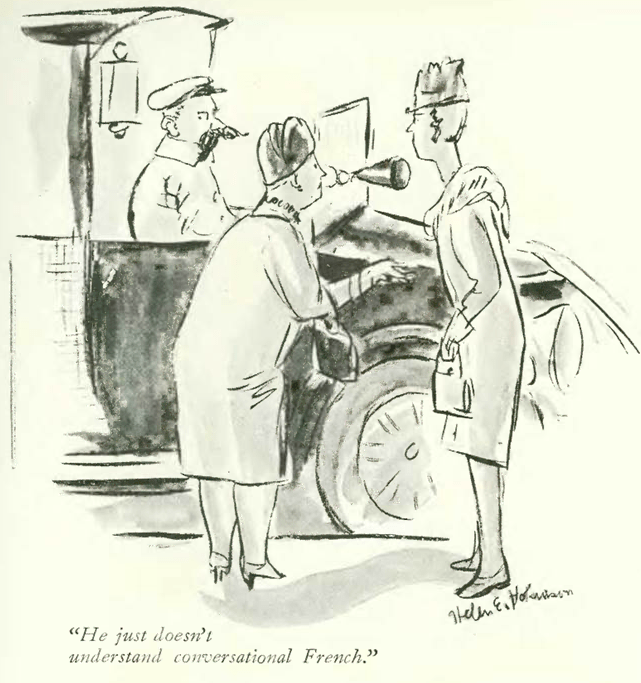

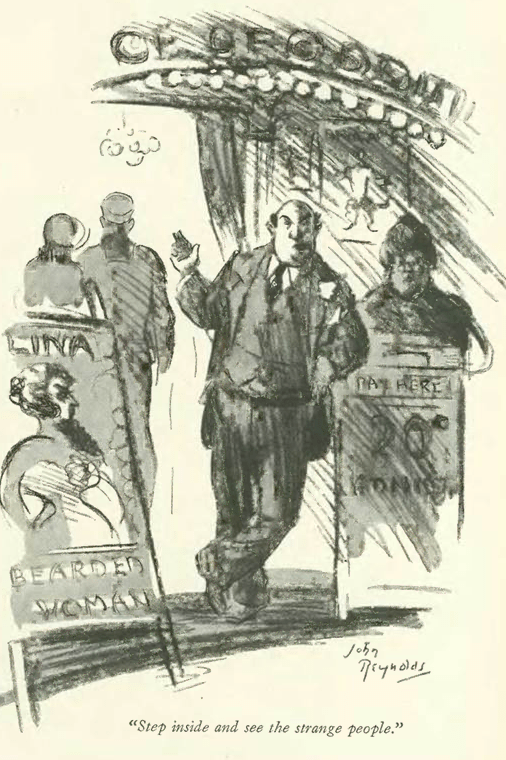

…on to our cartoonists…Helen Hokinson contributed this two-page spread on the challenges of visiting an old friend (click to enlarge)…

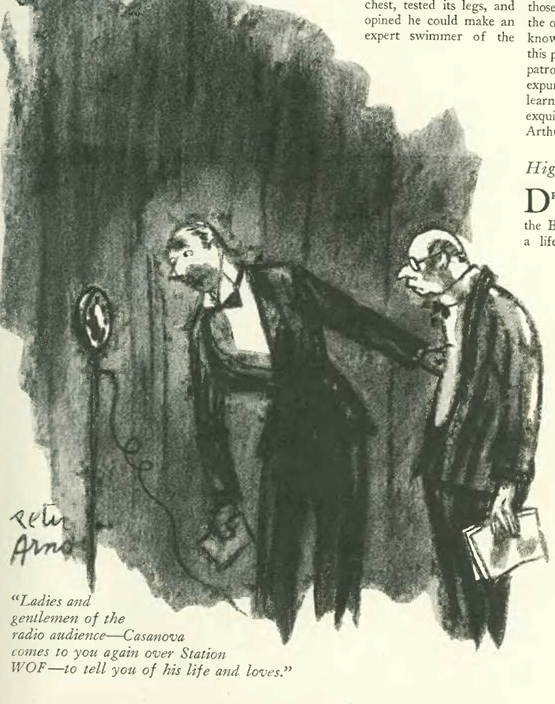

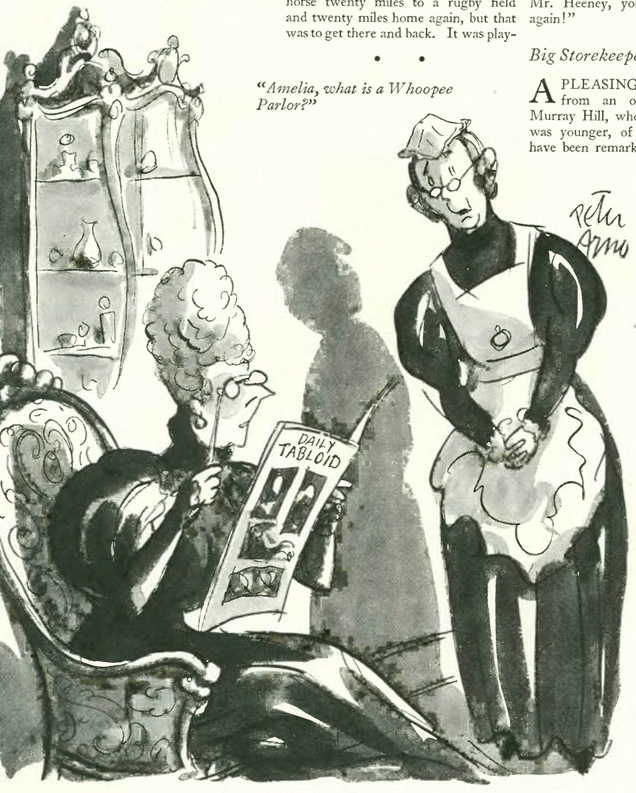

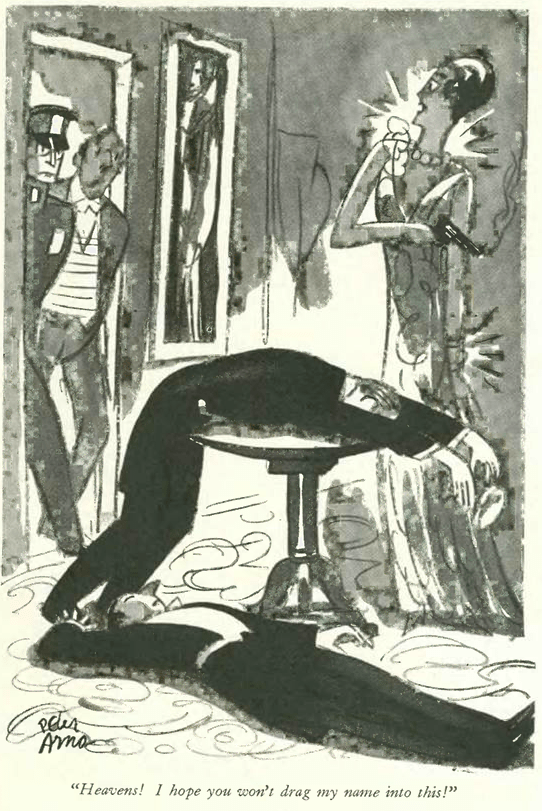

…Peter Arno looked in on a cheapskate at a posh restaurant…

…Bruce Bairnsfather visited the talkies…

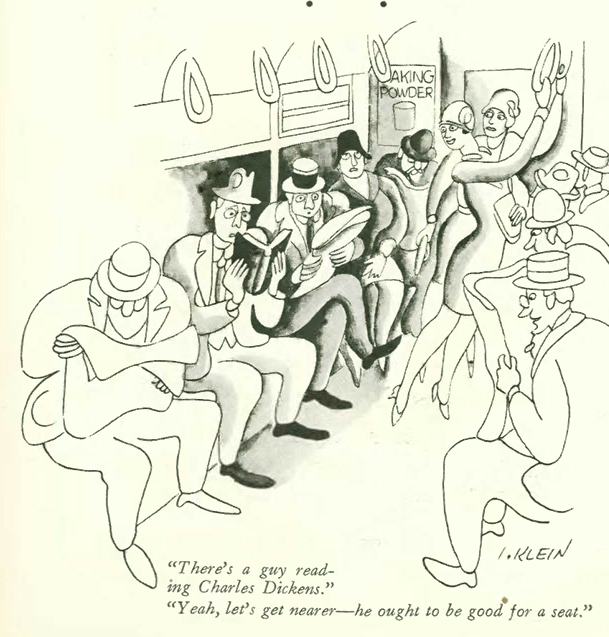

…Justin Herman examined the literary life of the street…

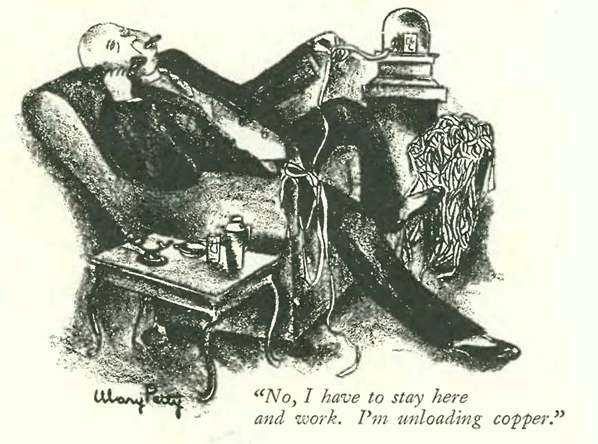

…Carl Kindl explored an awkward moment from the annals of technological advancements…

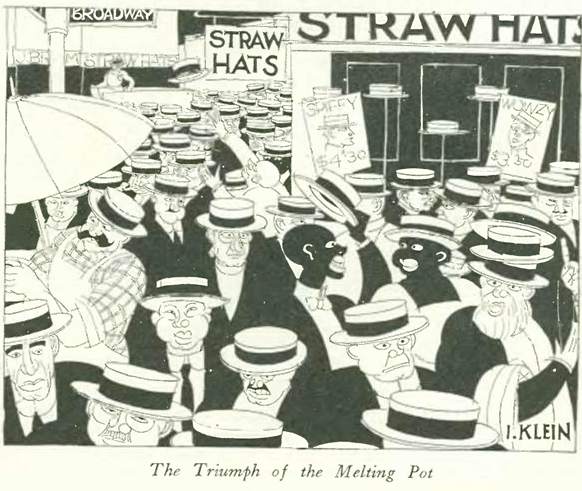

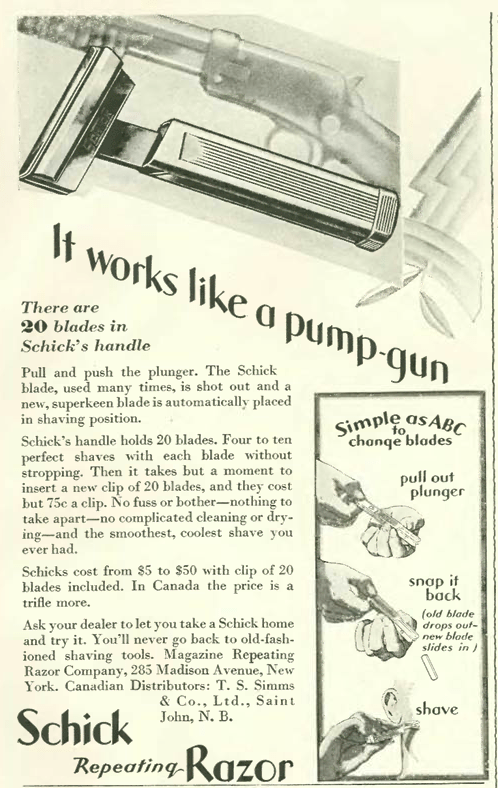

…and Isadore Klein illustrated the hazards of the tonsorial trade…

Next Time: The Last Hurrah…

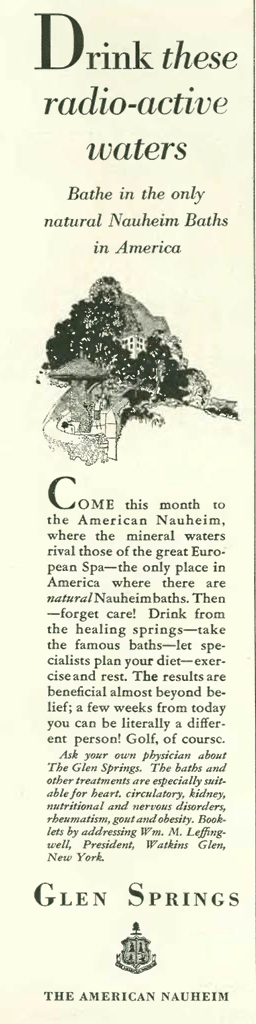

Why they called the waters “radio-active” escapes me. There were a lot of quack medical cures floating around in the 1920s—some of them quite dangerous—so I’m guessing that the proprietors of Glen Springs were adding radium to the water in some of their treatments, or maybe just claiming that radium was present in the water. Although Marie Curie (a pioneering researcher on radioactivity) and others protested against radiation therapies, a number of corporations and physicians marketed radioactive substances as miracle cure-alls, including radium enema treatments and radium-containing water tonics.

Why they called the waters “radio-active” escapes me. There were a lot of quack medical cures floating around in the 1920s—some of them quite dangerous—so I’m guessing that the proprietors of Glen Springs were adding radium to the water in some of their treatments, or maybe just claiming that radium was present in the water. Although Marie Curie (a pioneering researcher on radioactivity) and others protested against radiation therapies, a number of corporations and physicians marketed radioactive substances as miracle cure-alls, including radium enema treatments and radium-containing water tonics.