And finally, a cartoon by Rea Irvin exploring the trials of the idle rich:

And finally, a cartoon by Rea Irvin exploring the trials of the idle rich:

As much as they affected a refined disinterest in the latest fads, The New Yorker editors were nevertheless impressed by the many electronic innovations in the 1920s consumer market. Although electricity in cities had been around for awhile, inventions to exploit this new resource would come into their own in the Jazz Age with the advent of mass-produced electrical appliances (refrigerators, toasters etc.).

So when the 1926 Radio World’s Fair opened at Madison Square Garden, the magazine was there to report on its many marvels in the Sept. 18 issue:

Although New York’s radio fair was doubtless the largest (akin to today’s annual Consumer Electronics Show), similar fairs were held in other major cities where broadcast radio was taking hold.

…and for comparison, an image from the 2016 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas:

To give you an idea of some of the stranger innovations in the world of 1920s radio, here is an image scanned from the Oct. 16, 1926 issue of Radio World magazine demonstrating the wonders of a wearable cage antenna, apparently through which the wearer could make or receive wireless broadcasts…

…and a detail of an advertisement from the same issue depicting a typical household radio for the time:

If all this looks crude, remember that in September 1926 broadcast radio was less than six years old. But it was big year for radio, with the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) establishing a network of stations that distributed daily programs. Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) would establish a rival network in 1928.

In other items, the magazine offered a lengthy profile on tennis legend Bill Tilden, and later in the sports section described his Davis Cup loss to Frenchman René Lacoste.

The same site today:

The nearby Murray Hill Hotel mentioned in the article would last another 20 years, falling to the wrecking ball in 1947:

American cinema did little to excite the writers or critics of The New Yorker, who considered European films, and particularly German ones, to be far superior to the glitzy and sentimental fare produced in Hollywood.

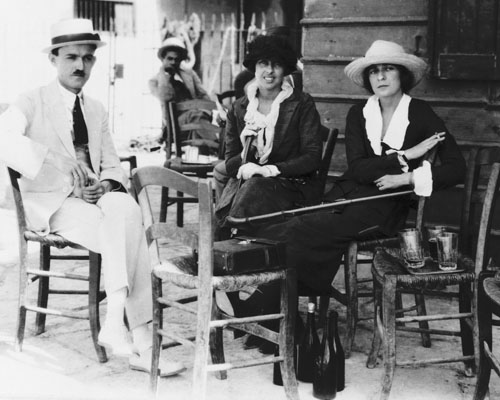

So when it was announced that Russian/Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein would be releasing Battleship Potemkin in New York City, the magazine’s editors in “The Talk of the Town” expressed both anticipation for the masterpiece as well as worries that American censors would slice the film to bits or even ban it outright.

The magazine’s film critic “OC” also expressed his concerns regarding censors:

The film was based on an historical event–a mutiny on the battleship Potemkin that occurred after the crew was served rotten meat for dinner. The sailors rebelled, seized the ship, and then attempted to ignite a revolution in their home port of Odessa, which in turn led to a massacre of citizens by Cossack soldiers on the city’s famed Potemkin Stairs.

The film would ultimately be released in December of 1926. Perhaps more on that in a later post.

The Sept. 11, 1926 issue also noted the passing of famed silent film star Rudolph Valentino, who died at age 31 of peritonitis and other complications. The “Talk” editors suggested that if anything, it was good for newspaper sales:

On the lighter side, The New Yorker men’s fashion columnist “Bowler” offered this observation of a new style suggested by Harpo Marx:

And to close, a couple of advertisements from the Sept. 11 issue…the first is a McCreery & Company ad illustrated by Gluyas Williams. These would become a series, featuring a milquetoast husband facing the daunting task of shopping for his wife, among other challenges…

…and this ad from Park Central Motors, depicting a child who’s all too aware of her standing in society…

Next Time: On the Airwaves…

Since most of us complain about the sad state of air travel these days, it’s nice to get a little historical perspective on this mode of transportation.

Ninety years ago the editors of The New Yorker were enamored with passenger air service, even though it was only available to those who were wealthy and had the stomach to actually fly in one of these things:

In the “Talk of the Town” section, The New Yorker editors marveled at the regular air taxi service available to Manhattanites:

The “huge” Yorktown might look crude to a traveler in 2016, but this was advanced stuff considering the Wright Brothers had made their first flight less than 23 years earlier. Planes like the Yorktown looked less like aircraft we know today and more like a trolley car with wings attached. And that window in the front wasn’t for the pilot. He sat up top in the open air:

But then again, the interiors of these planes were no picnic, either. Imagine sitting in this while crashing through a storm:

Other items from the Sept. 4, 1926 “Talk” section included a bit about the former president and then Supreme Court Justice William Howard Taft, and his rather ordinary life in Murray Bay. An excerpt:

At the movies, The New Yorker gave a lukewarm review of the much-ballyhooed film Beau Geste:

And although Gloria Swanson was one of the biggest stars in the Silent Era, The New Yorker was never a big fan of her films:

And finally, this advertisement from Houbigant, featuring a drawing of an elegant woman with an impossibly long neck. I wouldn’t want her sitting in front of me at the movies…

Another ad (from the Sept. 11 issue) also depicted this ridiculously giraffe-like neckline:

Next Time…Battleship Potemkin…

Next Time…Battleship Potemkin…

It’s the dog days of summer, and the editors of The New Yorker are seeking various distractions to take their minds off of the broiling late season heat.

In the Aug. 21, 1926 issue (bearing an appropriate cover image by H.O. Hofman of bathers taking a refreshing dip), “The Talk of the Town” suggested that it was a good time for even the natives to take a boat tour of their beloved island:

In the following Aug. 28 issue, the “Talk” editors ducked out of the sun to visit the American Museum of Natural History.

There they found curators busy reorganizing displays of dinosaurs and various stuffed beasts of the wild:

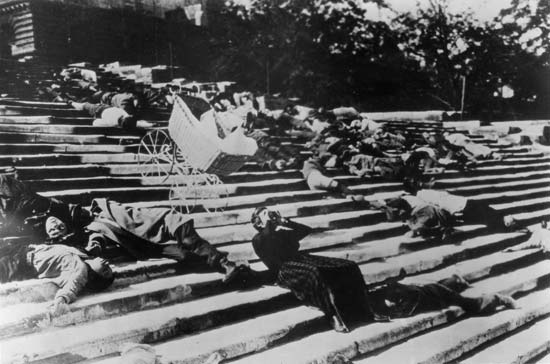

The magazine also profiled New York City native Gertrude Ederle, who became the first woman to swim across the English Channel in August of 1926:

Even Janet Flanner, the magazine’s Paris correspondent, commented on the event, noting Europe’s jealous reaction to an American’s seizing of the record:

Ederle would return home to a ticker tape parade along the Canyon of Heroes in the Financial District, and would also be feted by 5,000 people who turned out on West 65th Street for a block party in her honor.

According to the excellent blog Ephemeral New York, Ederle received offers from Hollywood and Broadway and was deluged by marriage proposals. But she returned to a quiet life, moving to Queens and working as a swimming instructor for deaf children–Ederle’s hearing was seriously damaged in the water of the Channel, but otherwise swimming must have been good for her health. She died at age 98 in 2003.

Keeping with the summertime theme, the magazine covered the Gold Cup Regatta, complete with illustrations by Johan Bull:

An early Barbara Shermund cartoon, always a delight…

Lois Long took her “On and Off the Avenue” column to Paris, where she cast a jaded eye at the behavior of American buyers of French fashion:

And finally, from the advertising department, this strange ad from Ovington’s, which seemed to be more concerned with promoting racial stereotypes than in selling dinnerware:

Next Time: Come Fly With Me…

It was 1926 and another marvel of science—talking pictures—was unveiled to audiences at Broadway’s Warners’ Theatre. It was here that the Warner Brothers launched their ‘Vitaphone’ talkies including The Jazz Singer, which would premiere the following year.

The Vitaphone soundtrack was not printed on the film itself, but rather recorded separately on phonograph record, the sound synchronized by physically coupling the record turntable to the film projection motor.

Don Juan was the first feature-length film to use the Vitaphone system, which was not a continuous soundtrack but rather a sprinkling of sound shorts (the musical score, performed by the New York Philharmonic, and various sound effects) throughout the film. No spoken dialogue was recorded.

Produced at a cost of $789,963 (the largest budget of any Warner film up to that point), the film was critically acclaimed and a box-office success. However, and predictably, The New Yorker was not so impressed with Vitaphone…

…or the acting of John Barrymore…

I have to agree with the critic, identified only as O.C., after viewing this TCM clip of the film on YouTube. Lacking a voice, silent actors had to exaggerate emotions onscreen, but Barrymore here is every bit the ham. This screen grab from the clip says it all:

The object of his gaze, Adriana della Varnese (played here by a young Mary Astor), reacts rather dramatically to his advances…can’t say I blame her…(however, the 44-year-old Barrymore and the 20-year-old Astor were having an affair at the time…)

A couple of interesting ads in the Aug. 14, 1926 issue, including this one featuring a couple of sneaky gents who’ve found a solution to life in dry America…

…and this not-too-subtle message from a swanky shop on Fifth Avenue:

Next Time: Time for a Facelift…

Above: Samuel Herman Gottscho photograph, New York City, Times Square South from 46th Street. General view of “Whiteway” toward Times Building, December 9, 1930. Museum of the City of New York

The lights of Broadway dazzled the editors of “The Talk of Town,” who commented on the changing displays that brightened The Great White Way.

Broadway hit its prime in the 1920s, when many old buildings originally used for housing or commercial interests became more valuable as places to hang brightly lit signs.

The “Talk” editors were more or less impressed by the displays. Despite their garishness, the Broadway lights were also a symbol of the youthful exuberance of Roaring Twenties New York:

The “Talk” editors sang the praises of the “aortic” Grand Central Station, which they dubbed a place of both dignity and efficiency that sorts a “surprisingly cheerful stream” of travelers with a certain rhythm, set in motion by an impassive gateman:

The Talk writers also added this lyrical observation of the traveling masses:

Talk also noted the recent travels of Cornelius Vanderbilt Jr., who was an apparent heir to the Vanderbilt fortune until he shunned high society and was disinherited by his parents for becoming a journalist and newspaper publisher. The Talk segment noted that Vanderbilt had returned from travels in Europe, where among other things until he rubbed elbows the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and observed the curious habits of people under his fascist rule:

Next Time: Talking Pictures…

Withering under a July heat wave, The New Yorker editors turned their thoughts to the cooling breezes that could be found blowing across the penthouse garden of real estate developer Robert M. Catts.

Catts erected the 20-story Park-Lexington office building at 247 Park Avenue in 1922, topping the building with his own penthouse apartment. Located near Grand Central Station, the building was innovative in the way it was built directly over underground railroad tracks leading into the station. The editors of The New Yorker, however, were more impressed by what was on top:

It was the rooftop garden, however, that sent the editors into a swoon:

Before World War II the apartment would have other notable tenants who would succeed Catts, including the violinist Jascha Heifitz. The apartment, and the building beneath it, were demolished in 1963 along with the adjoining Grand Central Palace building, which was replaced in 1967 with 245 Park Avenue:

In other news, Arthur Robinson wrote a somewhat sympathetic profile of Babe Ruth, observing that Ruth’s “thousand and one failings are more than offset by his sheer likableness.”

Curiously, the Yankees were having a better year in 1926, but there was scant mention of baseball in the pages of The New Yorker, the magazine preferring to cover classier sports such as golf, polo, tennis and horse racing. Another sport of interest was yacht racing, with Eric Hatch covering the races at Larchmont augmented by Johan Bull’s illustrations:

The magazine continued to have fun with the androgynous fashion trends of the Roaring Twenties. This appears to be an early Barbara Shermund cartoon:

Next Time: The Lights of Broadway…

The Roaring Twenties were an age when many social norms were challenged, including gender roles. Stars such as Marlene Dietrich wore men’s clothing, and many women went to work (women in the workplace increased by 25 percent) and they smoked in public.

At first smoking in public was associated with the wild behavior of flappers, but thanks to American advertising know-how, things quickly changed. What helped spark that change was this controversial 1926 magazine and billboard advertisement:

Naturally, the editors of “The Talk of the Town” had something to say about all the fuss:

Give dubious credit to Chesterfield for cracking a barrier. And thanks to mass marketing, what was rare and shocking quickly became commonplace. Subsequent cigarette ads featured women who didn’t need a man to blow them any smoke; they were independent, successful and famous:

The editors of The New Yorker obviously loved cars and the advertising they attracted, so for the July 24 edition they dispatched a writer and an artist to the motor races at Atlantic City to record the momentous event. However, staff writer Eric Hatch seemed as interested in the attire of the drivers as in the race itself:

And then there were Dave Lewis’s breeches…

…and the wild stockings worn by the race’s starter, Fred Wagner:

Illustrator Johan Bull offered his own observation about Wagner’s stockings, among other things:

In a separate column in the magazine (simply titled “Motors”) Hatch marveled at the amazing new road to Jamaica (Queens) that featured four lanes, two in each direction, with drivers approaching breakneck speeds near 40 miles per hour:

As for speed, back then a basic car was a far cry from an Indy racer, and strained to do more than 45 mph. Luxury cars could go faster, but the quality of tires, brakes and roads were so poor that anyone exceeding 60 mph would likely blow a tire.

Next Time: A Castle in Air…

The glories of summertime filled the pages of the July 17, 1926 issue. The cover featured a stylish young couple enjoying a romantic evening on a moonlit lake, while the inside pages were filled with all sorts of outdoor activities ranging from dining and dancing to open air concerts and golf, lots of it.

There was a lengthy profile by Herbert Reed on golfing great Bobby Jones, a mere boy of 24 who competed as an amateur but often beat top pros such as Walter Hagen and Gene Sarazen (in a few years Jones would help design the Augusta National Golf Club and co-found the Masters Tournament).

In “Sports of the Week,” Reed wrote about Jones’s second U.S. Open win, in Columbus, Ohio. Johan Bull offered this rendering of the runners-up:

And with the warm weather the tops were open on automobiles for both the rich:

And the not-so-rich:

And finally, Lois Long, fed up with reviewing restaurants, fires off a column about the sad state of drinking in America:

Next Time: Blowing Smoke…