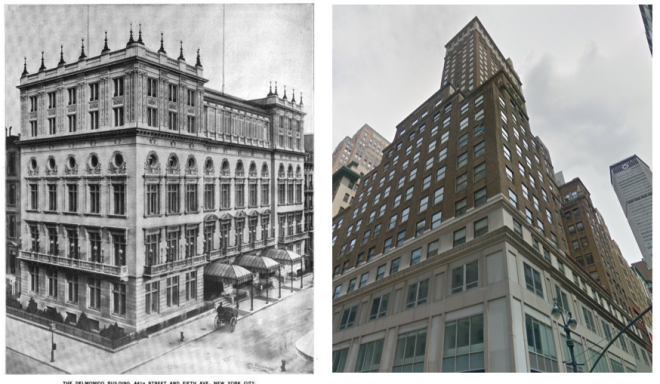

Photo above via themindcircle.com

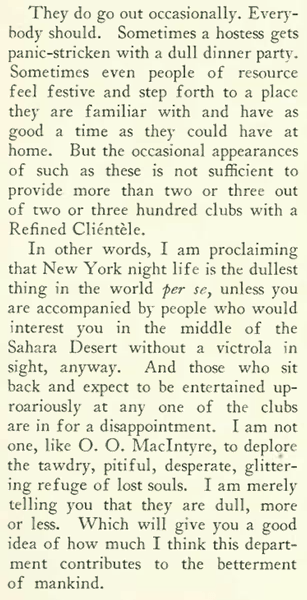

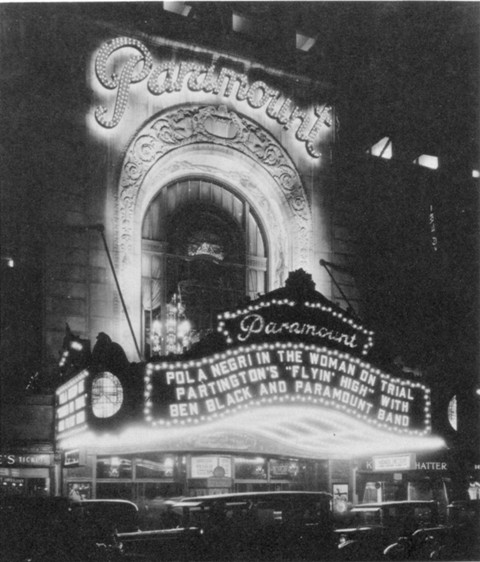

With Christmas fast approaching, The New Yorker was getting into the spirit of holidays, especially with all of the advertising revenue it gained from merchants who targeted its well-heeled readership.

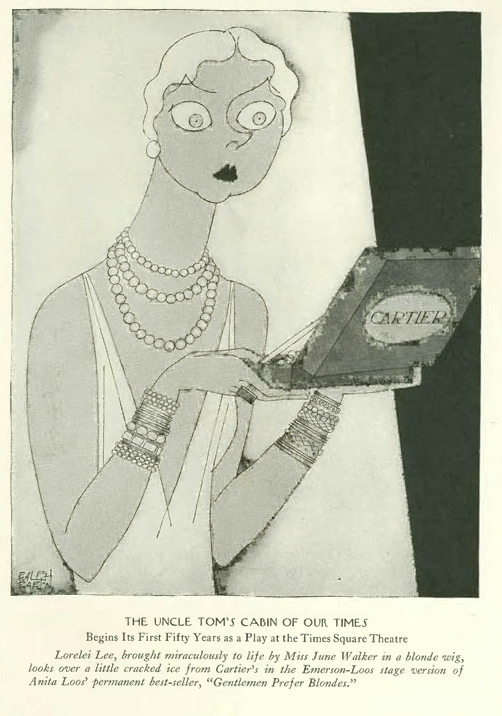

Lois Long continued to write both of her weekly columns for the magazine–her observations on fashion along with ideas for Christmas shoppers in “On and Off the Avenue” (“Saks’ toy department has some of the loveliest French notepaper for tiny children…”) and her musings on nightlife in “Tables for Two.”

In contrast to her rather light mood expressed in the fashion column, Long was feeling far from jolly in her “Tables” observations of New York’s nightlife:

As you might recall, in a previous column Long tossed a “ho-hum” in the direction of the famed Cotton Club. Perhaps Prohibition was taking its toll on the hard-partying columnist.

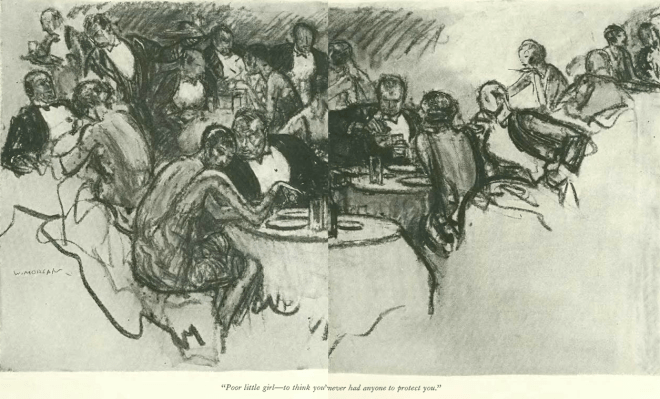

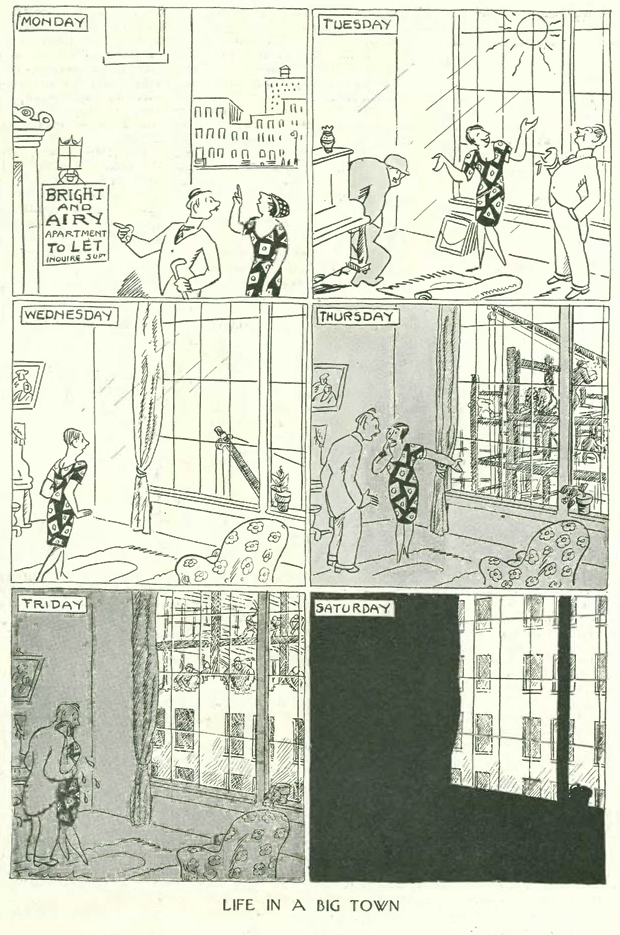

Nevertheless, the holiday spirit was upon with The New Yorker, in the cartoons (this one by Helen Hokinson)…

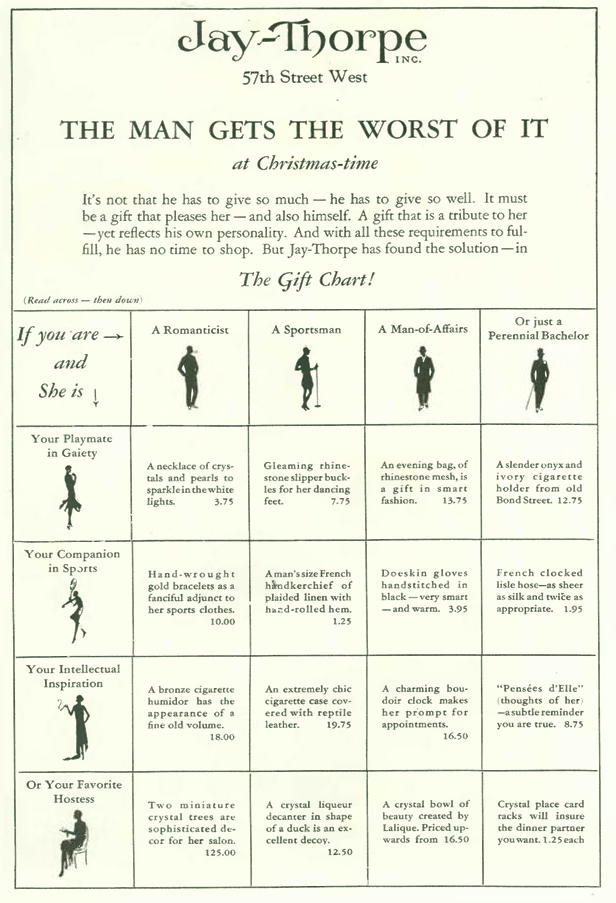

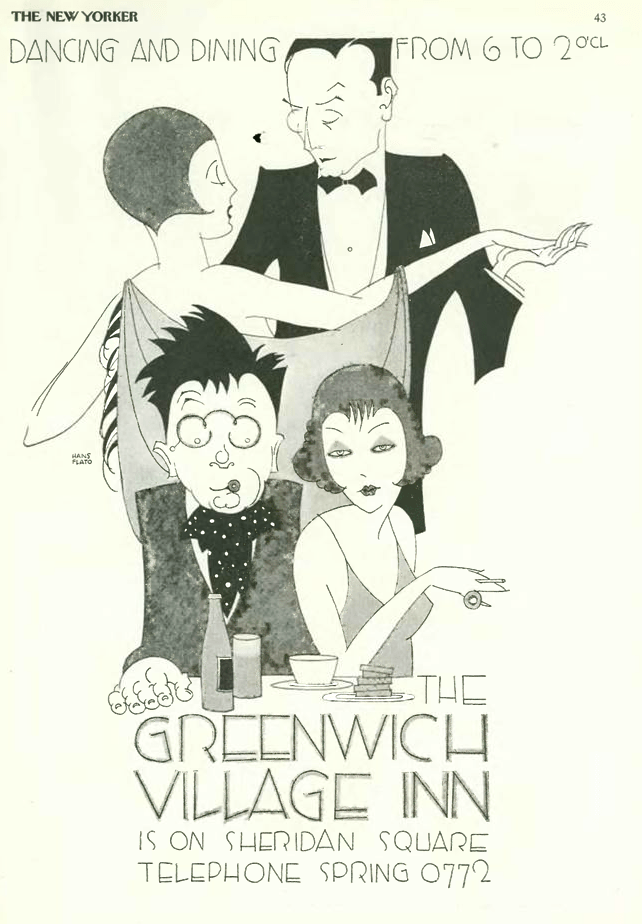

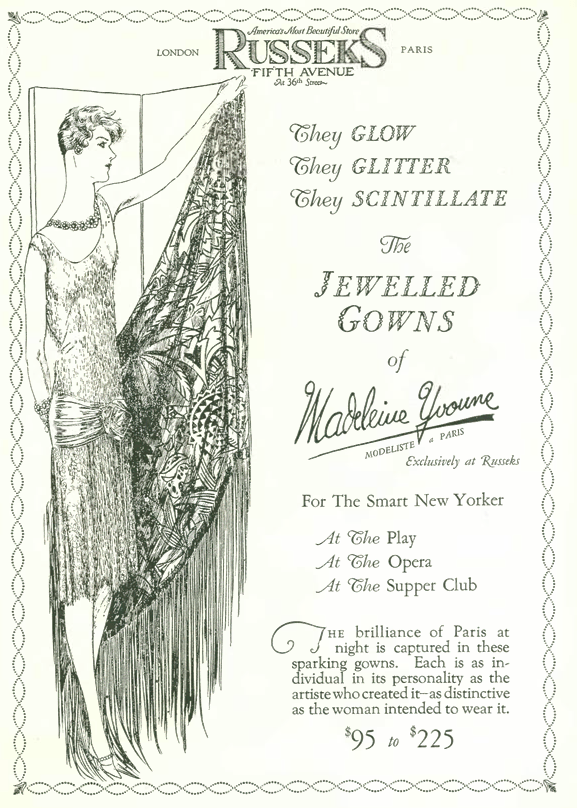

…and in various advertisements.

Note this advertisement (below) from Russeks. The comics in The New Yorker famously poked fun at the comic pairings of rich old men and their young mistresses, but this ad seemed to glorify such a pairing while suggesting that an older man of means must invest in fine furs if he is going to hang on to his trophy wife or mistress, in this case a young woman who appears to be nearly eight feet tall…

I liked this ad from Nat Lewis for the simple line drawing…

…but the ads for Elizabeth Arden, which for years featured this “Vienna Youth Mask” image, always creep me out.

The mask was made of papier-mâché lined with tinfoil. Although not pictured in the ad, it was also fitted to the client’s face. The Vienna Youth Mask used diathermy to warm up the facial tissues and stimulate blood circulation.

In a 1930 advertisement, Elizabeth Arden claimed that “The Vienna Youth Mask stimulates the circulation, producing health as Nature herself does, through a constantly renewed blood supply. The amazing value of this treatment lies in the depth to which it penetrates, causing the blood to flow in a rich purifying stream to underlying tissues and muscles…charging them with new youth and vigor. It stirs the circulation as no external friction or massage can possible do.”

I don’t believe this claim was backed up by medical research, but as we all know, Elizabeth Arden made a bundle from these treatments and the various creams and potions that came with it.

Next Time: Race Matters…