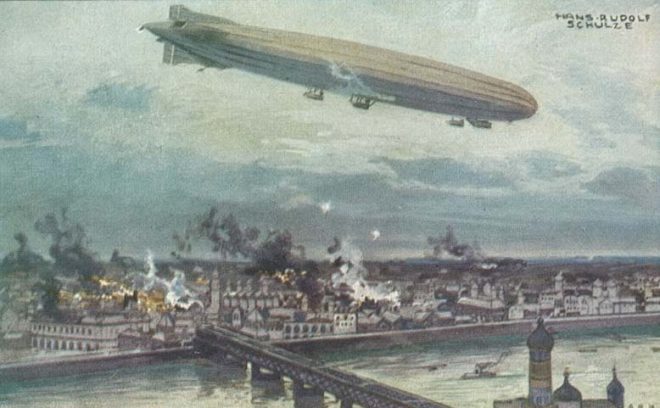

Just a decade after German Zeppelins sowed terror across the skies of Europe and Great Britain, Germany’s new Graf Zeppelin was enthusiastically welcomed by a throng gathered at Lakehurst, New Jersey, the massive airship having completed its first intercontinental trip across the Atlantic.

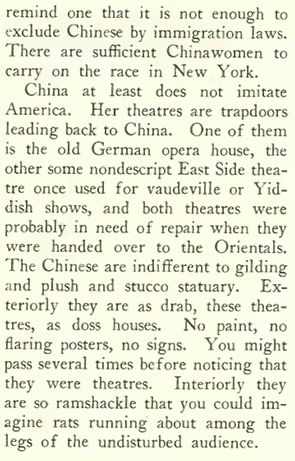

It had been only ten years and two months since German Zeppelins dropped their last bombs on the British, which had dubbed the airships “baby killers” for the mostly civilian casualties they inflicted. Beginning in 1915, Zeppelin raids on London killed nearly 700 and seriously injured almost 2,000 over the course of more than 50 attacks. It must have been a terrifying sight, something straight out of science fiction — flying ships more than the length of two football fields, blotting out the stars as they loomed overhead. Their size, however, was also their downfall, as Britain soon developed air defenses (searchlights, antiaircraft guns, and fighter planes) that shot many of these hydrogen gasbags out of the sky (77 of Germany’s 115 airships were either shot down or disabled).

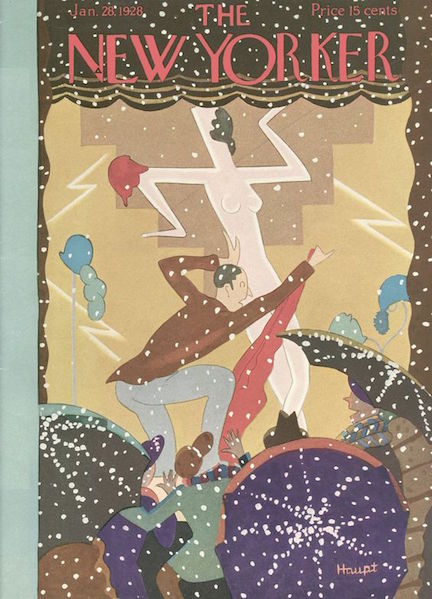

So when the 776-foot Graf Zeppelin loomed over the New York City skyline on Oct. 15, 1928, the reaction was one of awe rather than terror. The New York Times heralded its safe arrival on the front page…

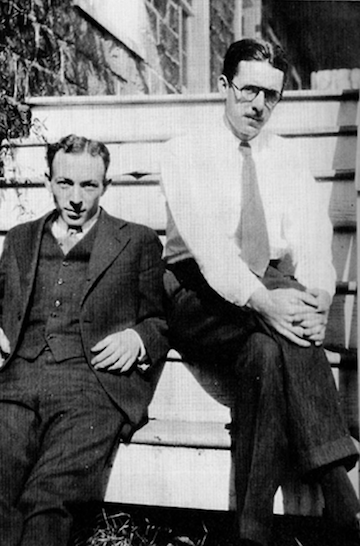

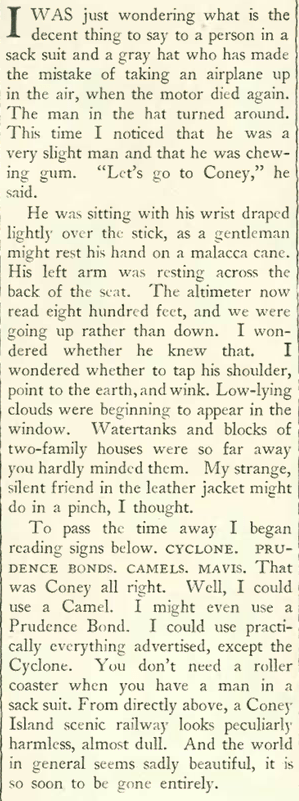

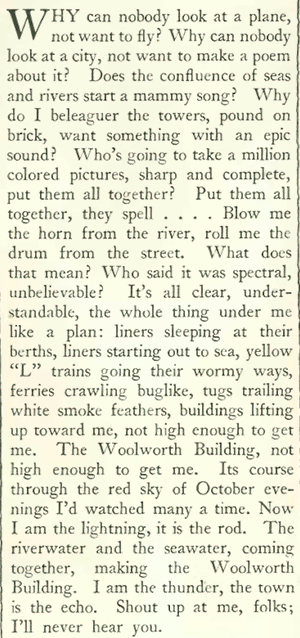

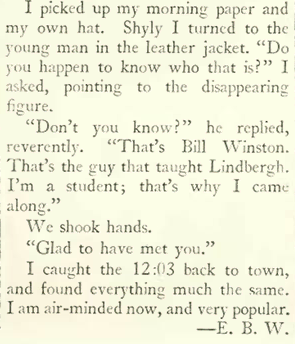

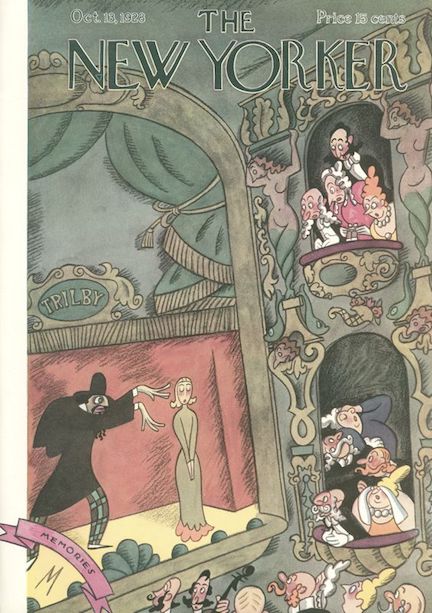

…and The New Yorker’s James Thurber (writing in “The Talk of the Town”) was on hand to assess the welcoming crowds gathered at Lakehurst, N.J….

…who in their enthusiasm could have easily destroyed the vessel, which had already sustained damage during a storm over Bermuda…

Reuben’s restaurant in New York seized the opportunity to cash in on the spectacle, boasting (in this hastily placed ad in the Oct. 27 issue) that the Graf Zeppelin’s passengers dined at their establishment on the very night of their arrival…

A final note: Considering the hazards of flying these ungainly, flammable machines (e.g. the Hindenburg in 1937) Graf Zeppelin flew more than one million miles in its career (the first aircraft in history to do so), making 590 flights (144 of them oceanic crossings, including one across the Pacific), and carrying more than 13,000 passengers — all without injury to passengers or crew.

* * *

Rough Riders

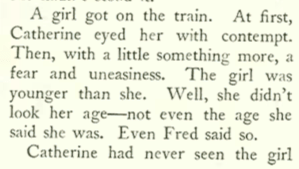

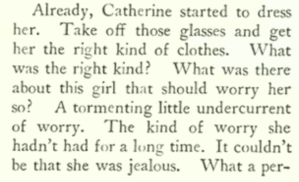

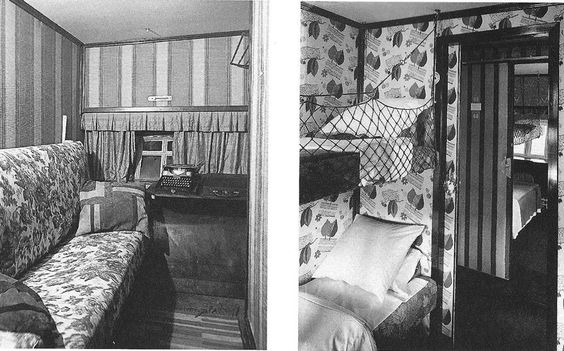

Back on the ground, “The Talk of the Town” looked in on a somewhat less exotic form of long-distance travel — the recently inaugurated coast-to-coast bus service from New York to Los Angeles:

* * *

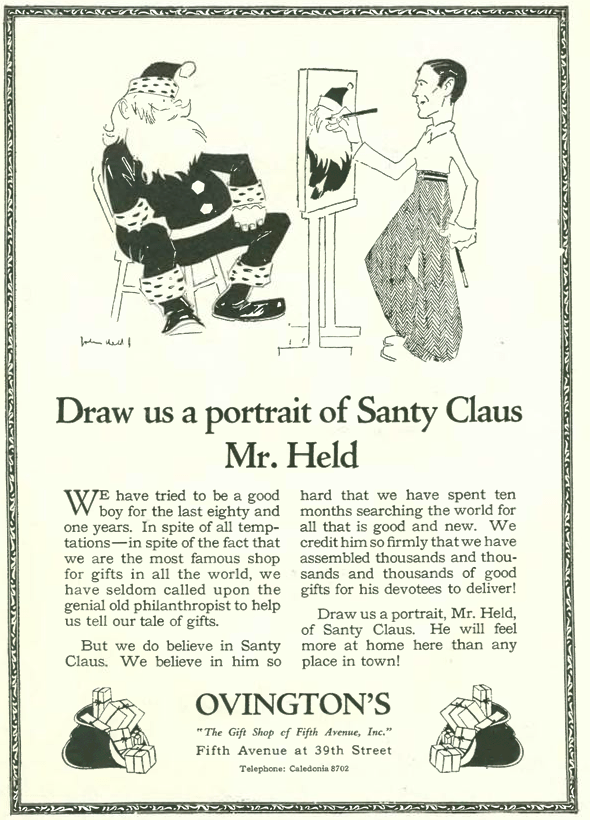

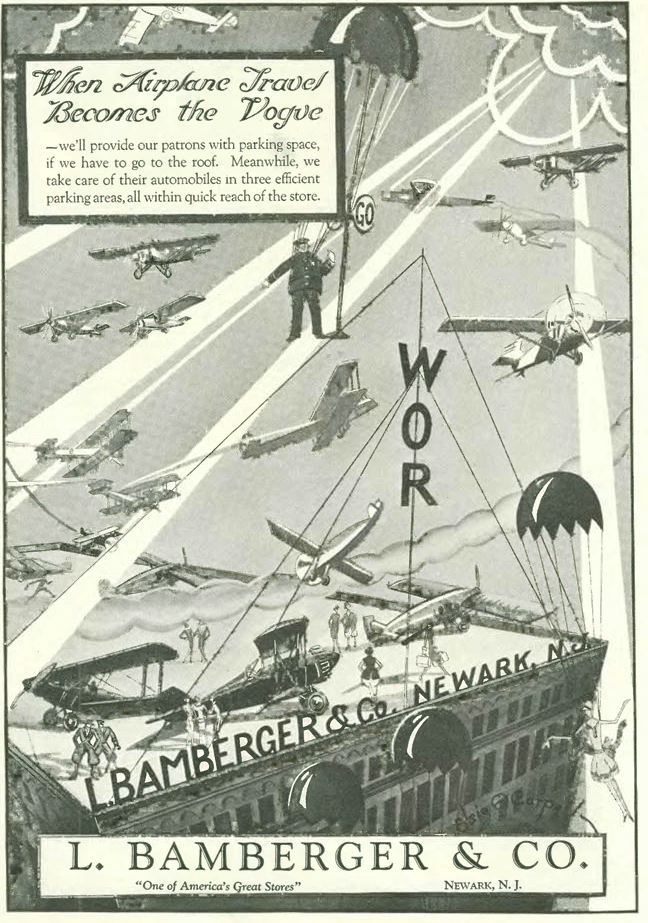

From Our Advertisers

On the subject of rolling transportation, Buick trumpeted the introduction of “adjustable front seats” in its silver anniversary model. Curiously, this improvement was touted as a convenience solely for women drivers…

Our cartoon (a two-pager) for Oct. 27 comes from Gardner Rea, the latest among The New Yorker’s staff to mock the quality of sound motion pictures. The cartoon is labeled at the bottom: “The Firtht One Hundred Per Thent Thound Movie Breakth All Houth Recordth.” (click image to enlarge)

* * *

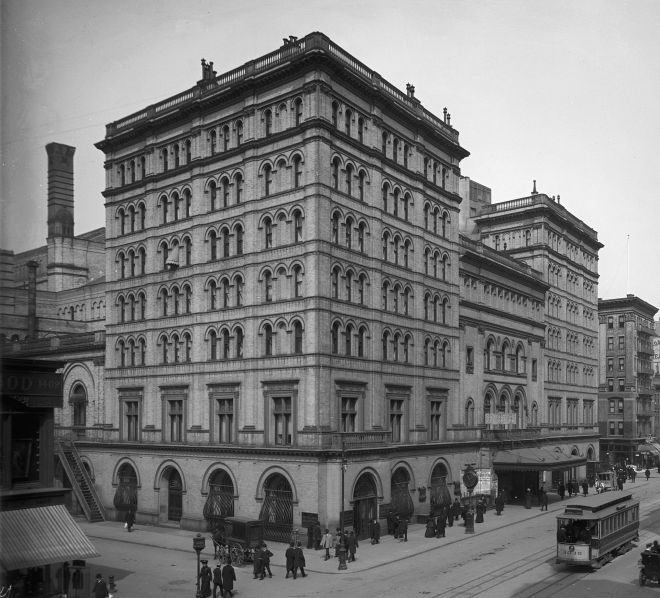

If you wanted to get a glimpse of New York’s “royalty” in 1928, you could secure a seat at the Metropolitan Opera, especially one with a view of its famed “Diamond Horseshoe” seats.

The “Diamond Horseshoe” described a ring of seats at the Metropolitan Opera House occupied by New York’s social elite. Not unlike today’s stadium skyboxes, the Met reserved these boxes for purchase by the wealthy. “The Talk of Town” for Nov. 3, 1928 noted how many of these were still held by the same families that had secured spots after the Met opened in 1883:

“Talk” also noted that some of the boxes in the Diamond Horseshoe were coming into new ownerships among the newly rich (E.F. Hutton) and even (gasp) immigrants such as Otto Kahn:

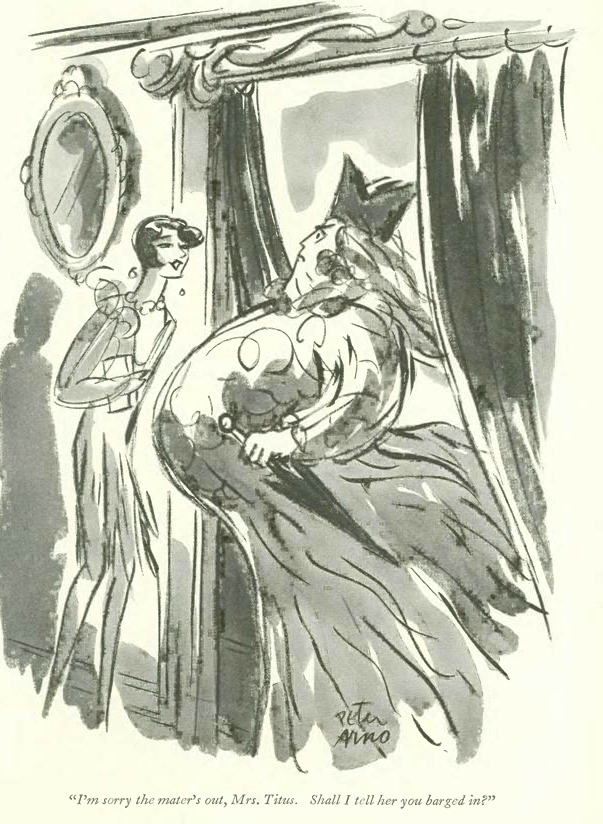

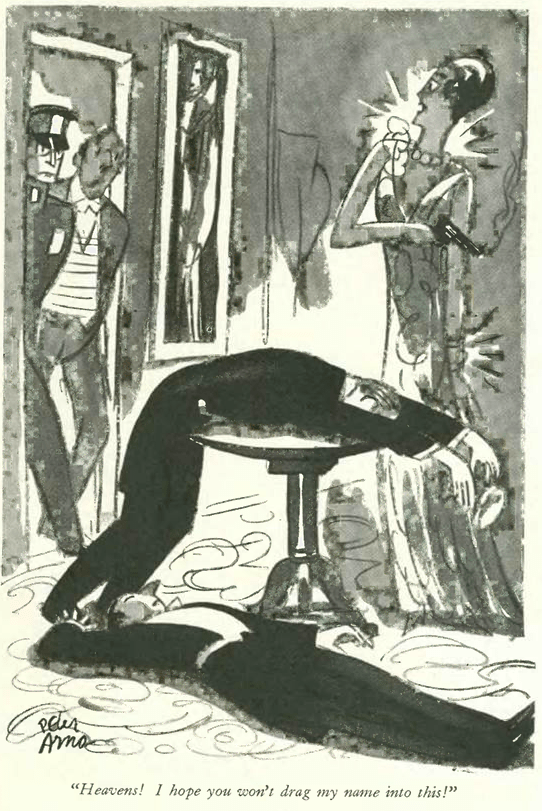

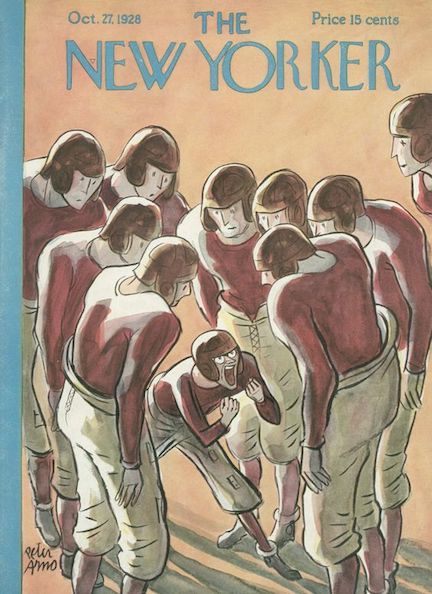

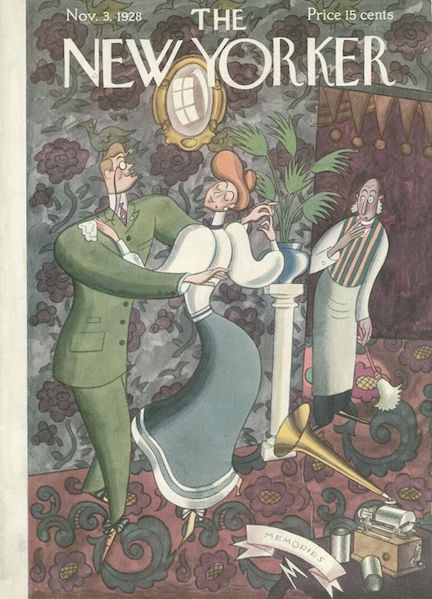

Also in the Nov. 3 issue was this cartoon by Peter Arno depicting one of the Met’s boxes stuffed with overfed toffs:

* * *

Poet With a Green Thumb

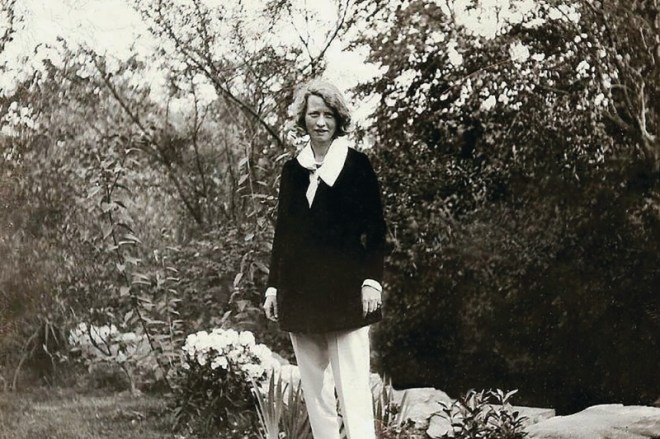

The Nov. 3 “Talk” also featured a bit by James Thurber on American poet and playwright Edna St. Vincent Millay, a major figure in New York’s Greenwich Village literary scene as well as a feminist leader. A Pulitzer-Prize winner (1923), Millay was also an avid gardener who preferred the solitude of her farm, Steepletop, to the limelight usually accorded a literary star:

Thurber noted that even her publisher, Harper & Sons, had to use an old photo of the publicity-shy poet for a new book release:

On the topic of photography, “Profiles” (written by film historian Terry Ramsaye) looked in on the quiet life of photography pioneer George Eastman, who founded the Eastman Kodak Company and popularized the use of roll film.

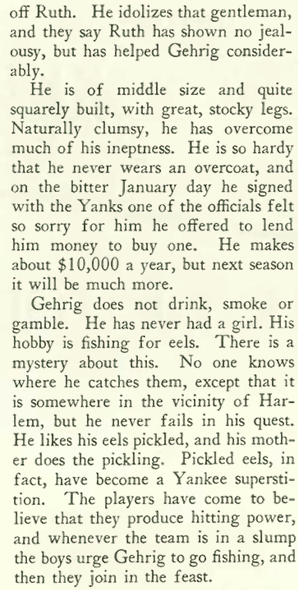

A quintessential “mamma’s boy,” Eastman never married…

…and by all accounts died a celibate less than four years after this profile was written, taking his own life at age 77. Suffering from intense pain caused by a spinal disorder, Eastman shot himself in the heart on March 14, 1932, leaving a note which simply read, “To my friends: my work is done. Why wait?”

Odds and Ends

Other items of note from the Nov. 3 issue included a humorous piece by Rube Goldberg, “The Red Light District,” in which the president of the Blink Stop-Go Traffic Company summons a doctor to treat a strange malady. The doctor gets held up by traffic lights on the way to the “emergency,” and when he discovers the problem is only hives, he shoots the patient. The piece was headlined by this artwork, also by Goldberg (shades of George Herriman and R. Crumb, yes?)…

Goldberg is still known today thanks to his series of cartoons depicting deliberately complex contraptions invented to perform simple tasks, such as the “Self-Operating Napkin” below, from 1931:

Cartooning’s highest honor, The Reuben Award, was named after Goldberg, who was a longtime honorary president of the National Cartoonists Society.

* * *

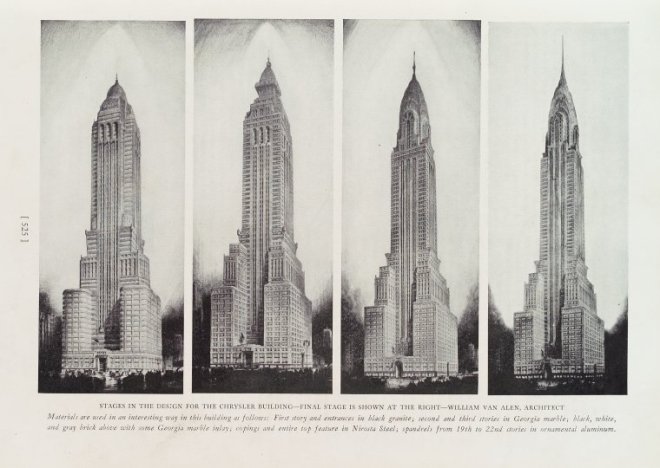

The Roaring 20s saw a rapid transformation of the New York skyline, with massive skyscrapers rising from the dust of old 18th and 19th century institutions. But few would signal the new age more than the Chrysler Building, an Art Deco landmark that would stand as the world’s tallest building for nearly a year (knocked from the top spot in May 1931 by the Empire State Building). Architecture critic George S. Chappell (“T-Square”) had this observation about the planned building:

* * *

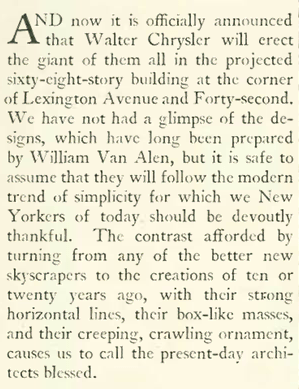

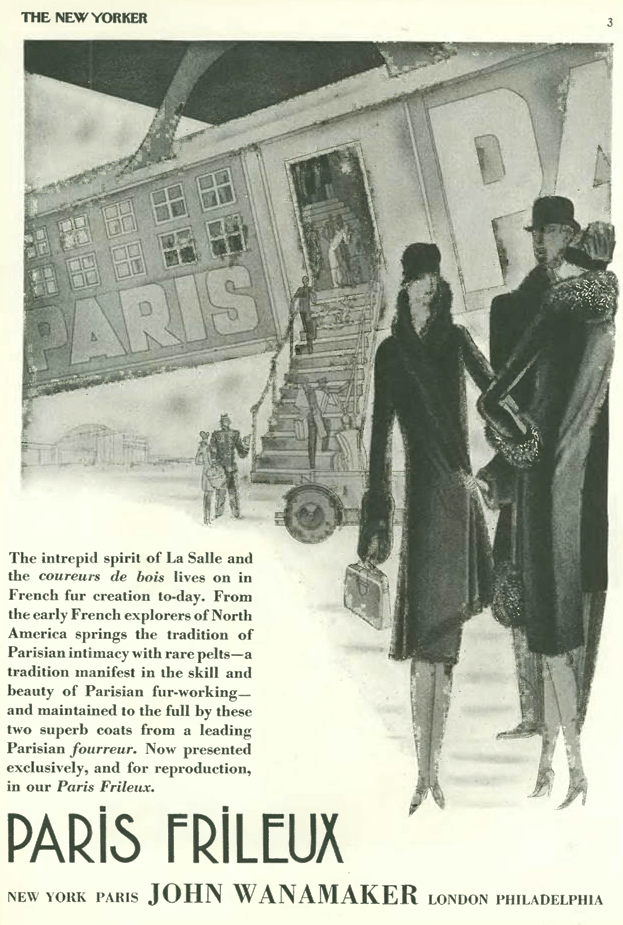

More from our advertisers…in the Nov. 3 issue Hawaii beckoned well-heeled New Yorkers who were contemplating the coming winter…

…and then there was this poorly executed ad for Kolster radios, the whole point seeming to be the drawing they commissioned from New Yorker cartoonist Peter Arno:

And finally, a cartoon by Alan Dunn, who looked in on an Ivy League football huddle:

Next Time: Diamond Lil…