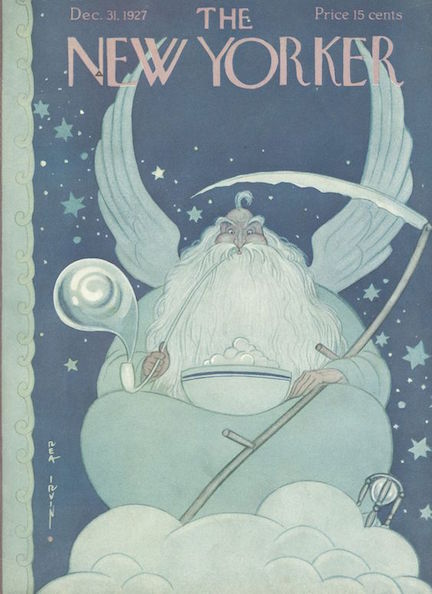

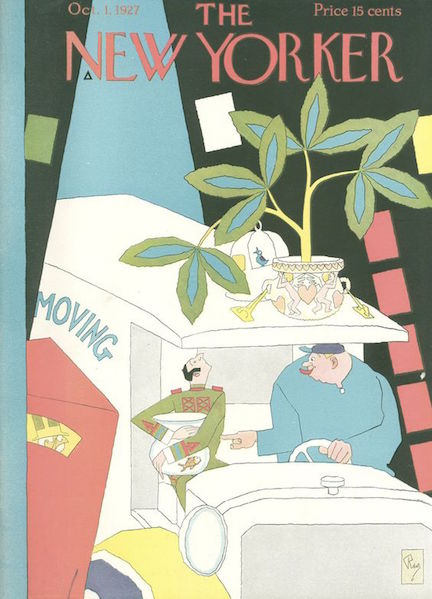

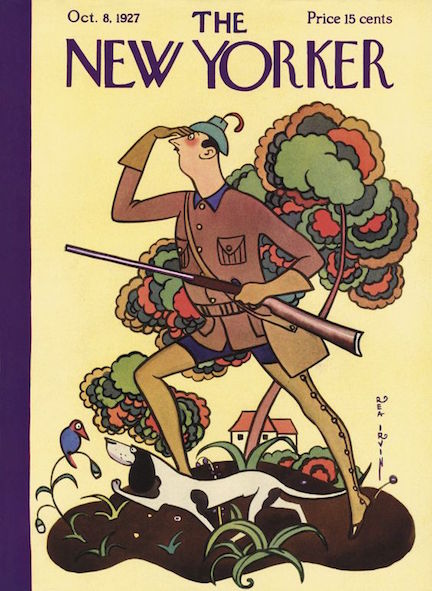

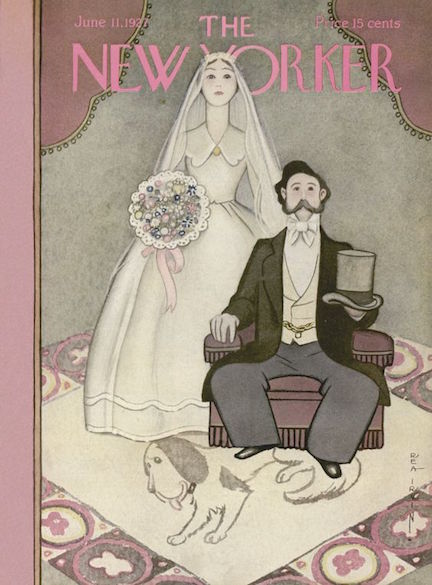

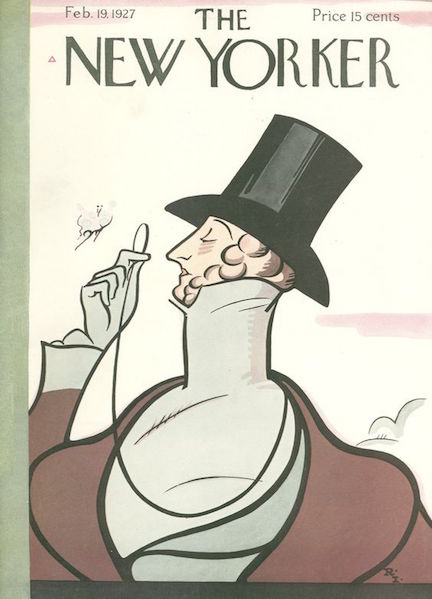

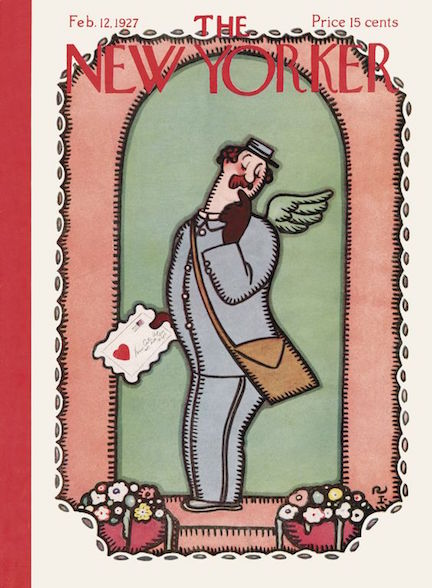

It what would become a longstanding tradition, The New Yorker marked its third anniversary by featuring the original Rea Irvin cover illustration from Issue No. 1. The New Yorker was a very different magazine by its third year, fat with advertising and its editorial content bolstered by such talents as Peter Arno, E.B. White and Dorothy Parker.

Parker livened up the magazine’s books section, mincing few words as she took on writers both great and not so great.

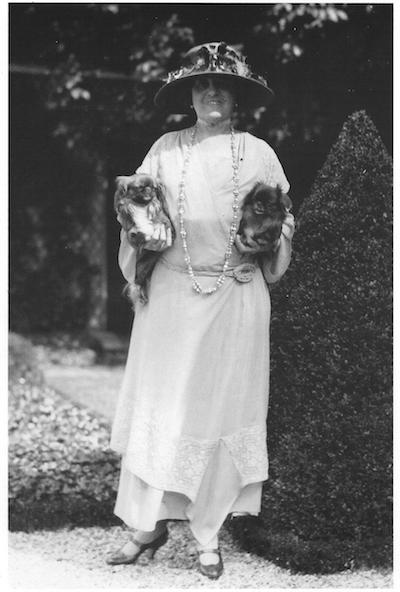

In the latter category was Aimee Semple McPherson, a 1920s forerunner of today’s glitzy televangelists. In her column “Reading and Writing,” Parker took aim at McPherson — “Our Lady of the Loud-speaker” — who had just published a book titled In the Service of the King.

McPherson (1890–1944) was a Pentecostal-style preacher who practiced “speaking in tongues” and faith healing in her services, which drew huge crowds at revival events between 1919 and 1922. She took to the radio in the early 1920s and in 1923 she based her ministry in Los Angeles at her newly completed Angelus Temple, which served as the center of the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel.

McPherson’s book detailed her conversion and her various hardships, including her mysterious “kidnapping” in 1926. Parker was having none of it:

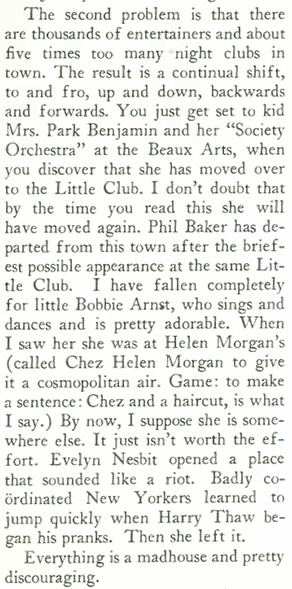

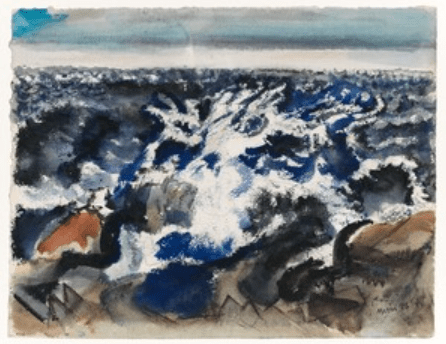

Parker was referring to events beginning on May 18, 1926, when the evangelist visited Venice Beach for a swim and went missing. Some thought she had drown, others claimed they saw a “sea monster” in the area. McPherson reemerged in June on the Mexico-Arizona border, claiming she had been kidnapped and held captive by three strangers.

Numerous allegations of illicit love affairs targeted McPherson during her years of fame, so some were inclined to believe she went missing in order to engage in a love affair with her sound engineer.

Upon her return to Los Angeles she was greeted by a huge crowd (est. 30,000 to 50,000) that paraded her back to the Angelus Temple. However many others in the city found McPherson’s homecoming gaudy and annoying. A grand jury was subsequently convened to determine if evidence of a kidnapping could be found, but the court soon turned its focus to McPherson herself to determine if she had faked the kidnapping. Parker thought the condition of the preacher’s shoes, after a long trek through the desert, were evidence enough of a sham:

McPherson, who was married three times and twice divorced, died in September 1944 from an apparent overdose of sleeping pills. She was 53. Her son Rolf took over the ministry after her death. Today McPherson’s Foursquare Church has a worldwide membership of about 8 million, and is still based in Los Angeles.

But How Do I Look?

The Feb. 25 issue profiled the young Jascha Heifetz, a Russian-born violin prodigy who seemed more interested in how he looked than in how he performed. An excerpt:

* * *

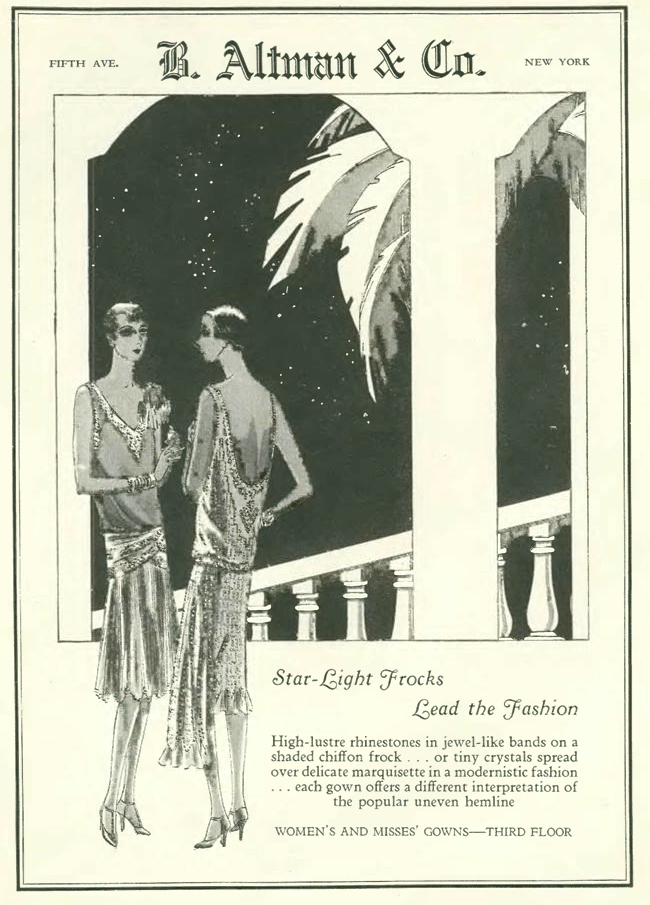

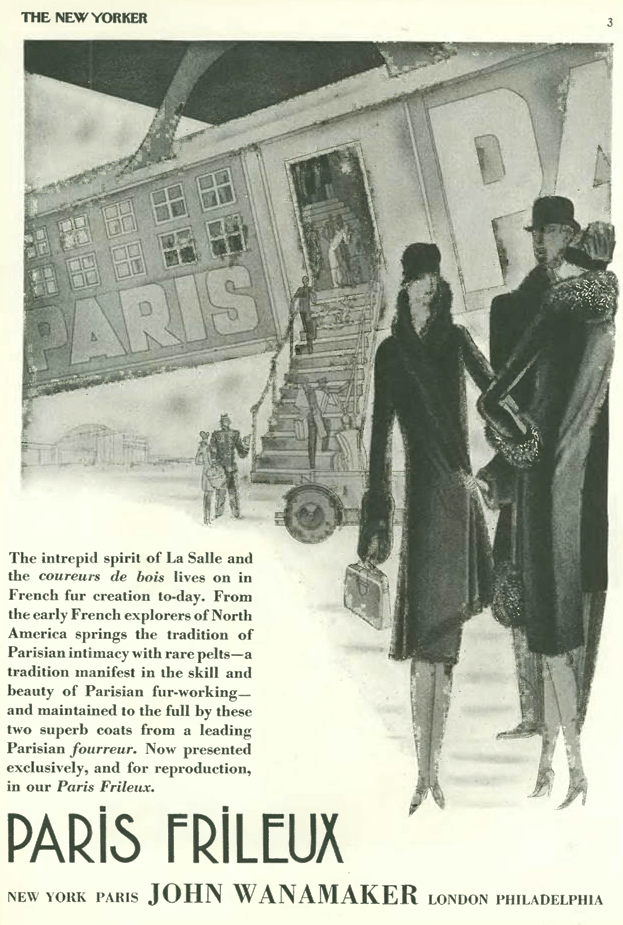

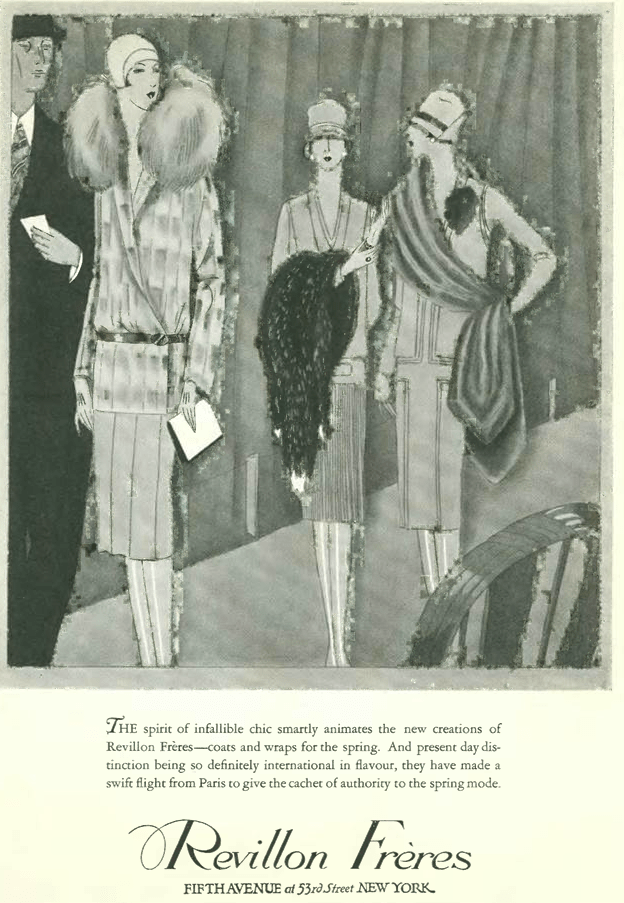

Speaking of fashion, one of the world’s greatest fashion designers, Paul Poiret, was seeing hard times in the late 1920s with his designs losing popularity in his native France and his formidable fashion empire on the brink of collapse. But Francophile New Yorkers, always hungry for French fashion, greeted Poiret with open arms when he arrived in the city in the fall of 1927.

It is something of a surprise, however, to find this advertisement in the Feb. 25 issue in which Poiret endorses Rayon, a man-made substitute for silk. We don’t usually associate synthetics with haute couture, but then again maybe Poiret just needed the money. Better living through chemistry, as they say…

Also in the issue was a sad, Prohibition-era advertisement that extolled the virtues of an oxymoronic “non-alcoholic vermouth”…

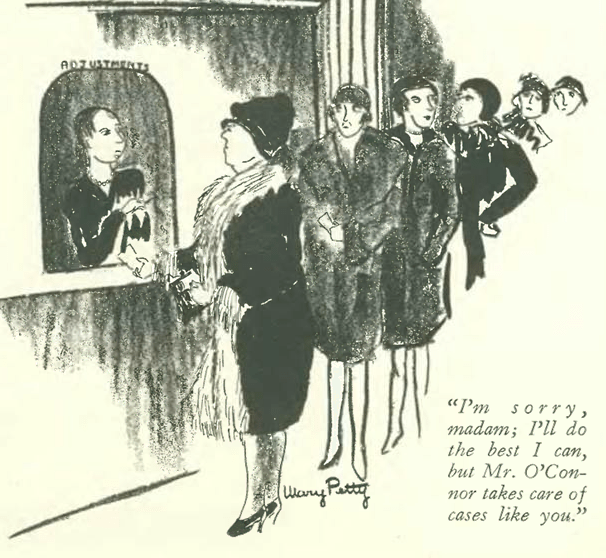

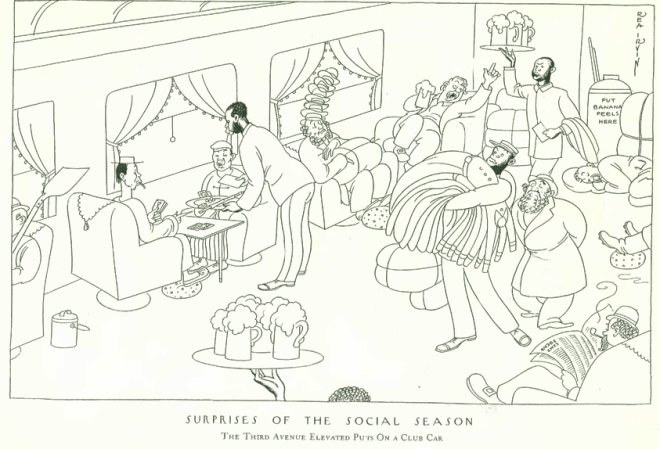

And finally from the Feb. 25 issue, a cartoon by Carl Rose…

* * *

One-eyed Monster

In the March 3 issue “The Talk of the Town” discovered the miracle of television during a visit to the Bell Telephone laboratories.

Lab researchers demonstrated a “receiving grid” with a tiny screen that displayed images broadcast across the expanse of an auditorium:

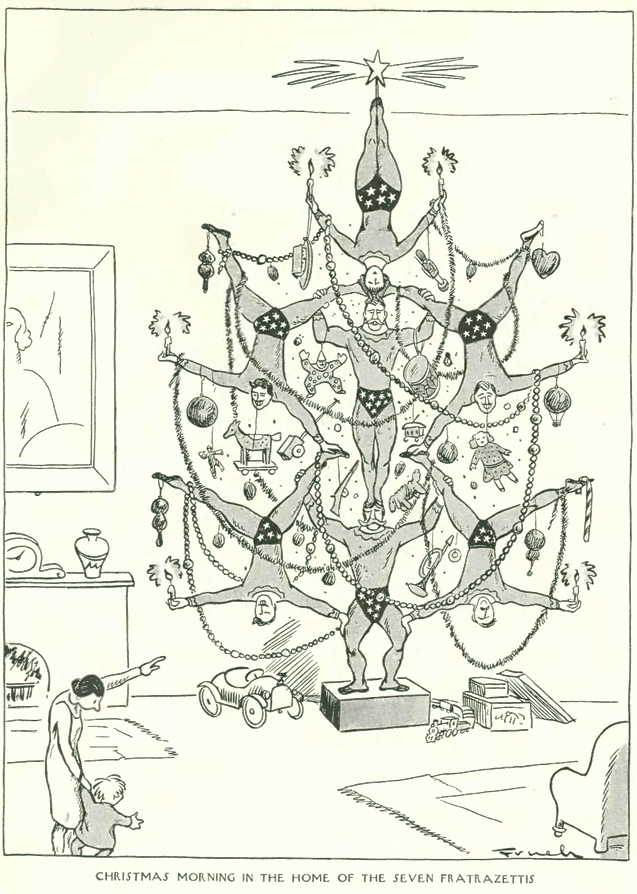

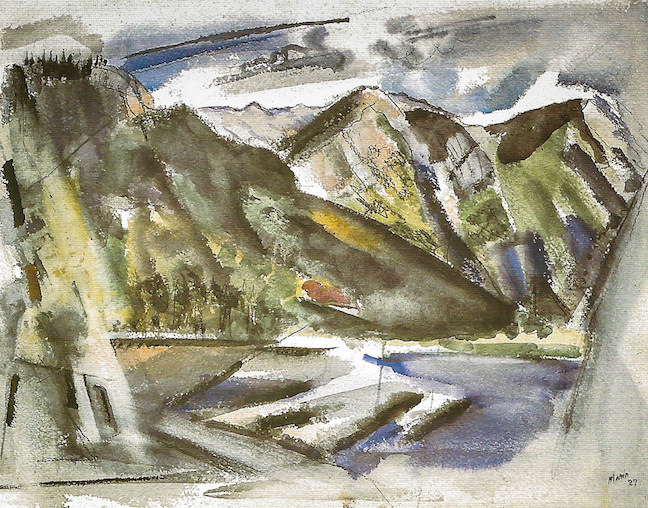

Another glimpse into the future in the March 3 issue came courtesy illustrator Al Frueh, who offered this fanciful look at the skyscraper of tomorrow:

* * *

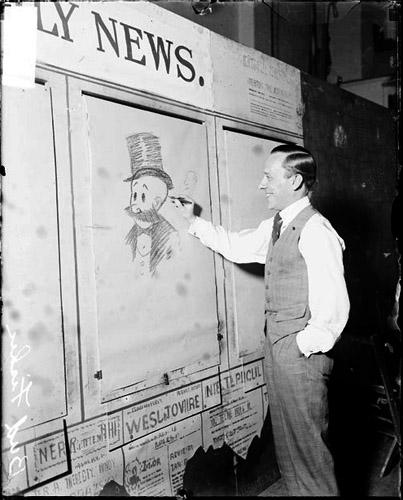

“Profile” featured the first installment of a four-part article (by Niven Busch Jr.) on a man who put America on wheels and into traffic jams. Excerpts:

And finally, from W.P. Trent, an analogy that would take on new meaning after the market crash…

Next Time: To Bob, Or Not to Bob…