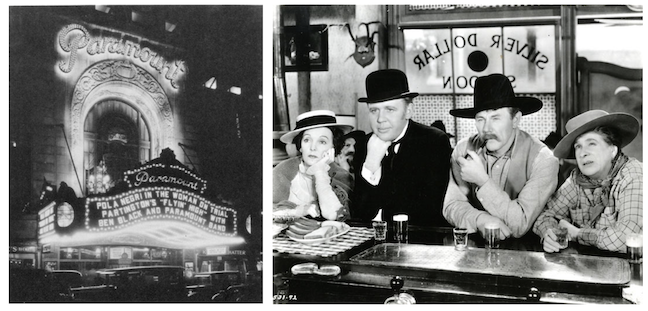

Above: Will Hays (center, top) was the enforcer and Fr. Daniel A. Lord was the author of the Production Code that was rigidly enforced beginning in 1934. They and others were responding to the sex, violence and other forms of "immorality" in such films as 1932's "Scarface" (with Paul Muni, pictured at left) and 1931's "Blonde Crazy" with James Cagney and Joan Blondell. (Wikipedia/cinemasojourns.com)

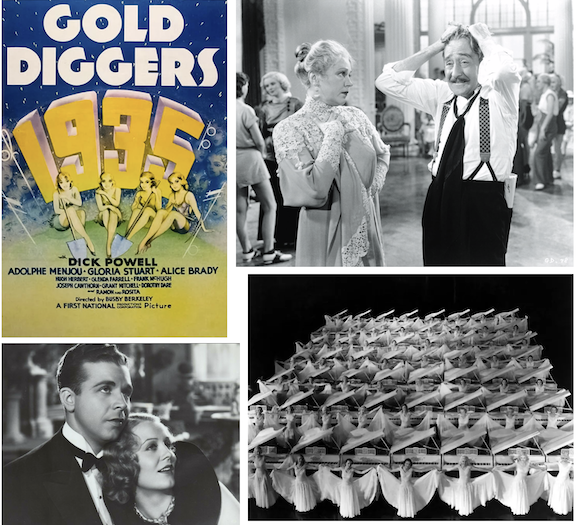

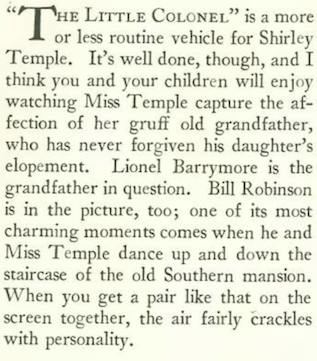

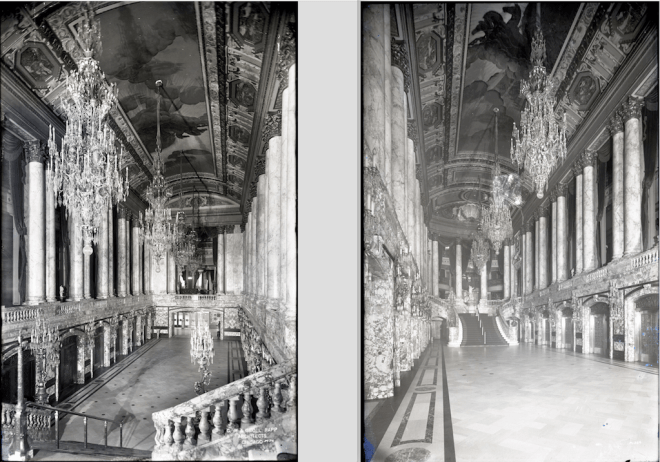

With the Production Code fully enforced, New Yorker film critic John Mosher found even less to get excited about during his visits to Manhattan’s cinemas.

The Motion Picture Production Code—a set of industry guidelines for the self-censorship of content—had been around for awhile, but it was mostly ignored until June 13, 1934, when an amendment to the Code required all films released to obtain a certificate of approval. Hoping to avoid government censorship and preferring self-regulation, studios adopted the Code.

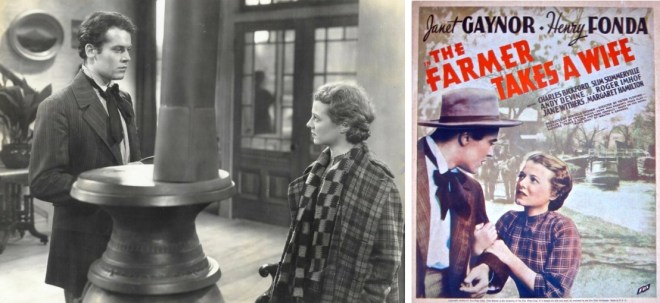

The Code’s effects were felt in such films as The Farmer Takes a Wife, a romantic comedy about a Erie Canal boatman, portrayed by Henry Fonda, who dreams of becoming a farmer (a role reprised by Fonda from the Broadway production of the same name; it was Fonda’s first break in films). Mosher was pleased by Fonda’s performance, but found the film adaptation to be corny and phony, filled with “bastard” dialect and schmaltzy musical numbers. “It is the sort of thing which is okayed by Purity Leagues…” Mosher concluded.

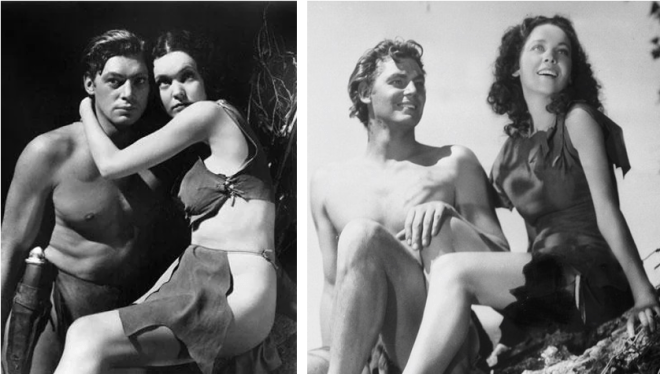

To get a clearer idea of what the Code did to the pictures, compare the scene from 1934’s Tarzan and His Mate (left), which was released two months before the Code went into effect, and Tarzan Escapes (right), from 1936.

* * *

Noted and Notorious

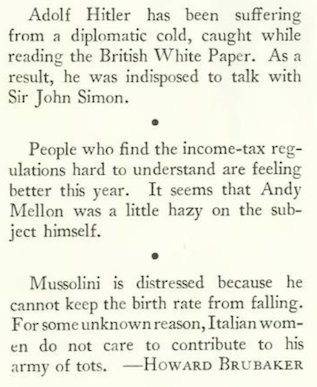

In his weekly column “Of All Things,” Howard Brubaker offered wry observations on the passing scene, including this latest brief that described the rise and fall of a very unlikely quartet of celebrities.

* * *

Titlemania

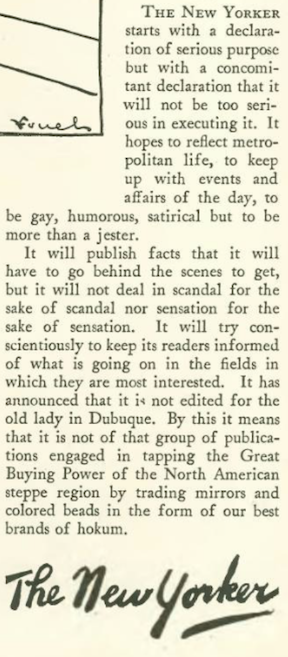

Lacking the strictures of Old World caste systems, Americans have had an anxious relationship with class signifiers. In a land where trade schools become universities overnight and their faculty members refer to one another as “doctor,” there is much confusion and hand-wringing in the honorifics trade. H.L. Mencken examined the proliferation of titles in his country, freely handed out without regard to merit. Excerpts:

* * *

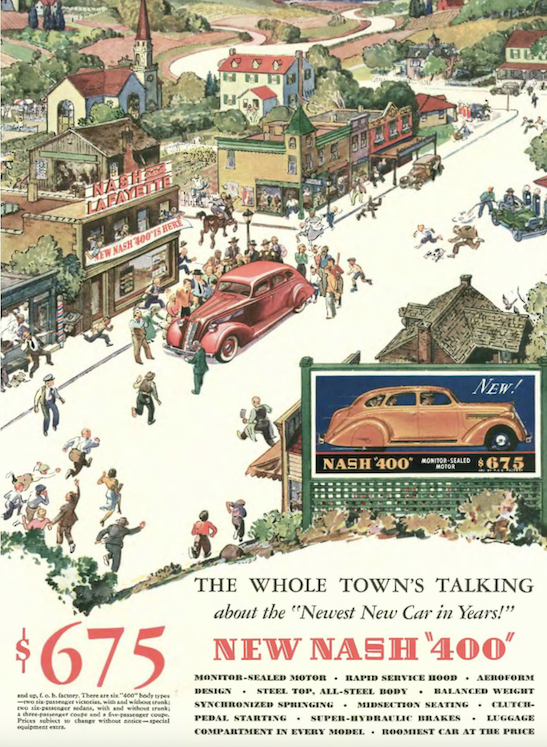

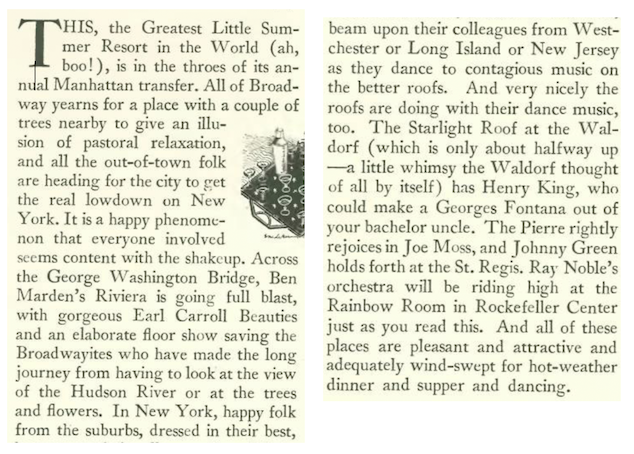

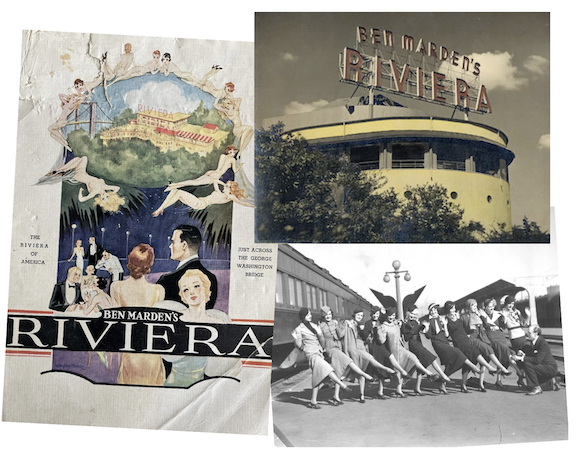

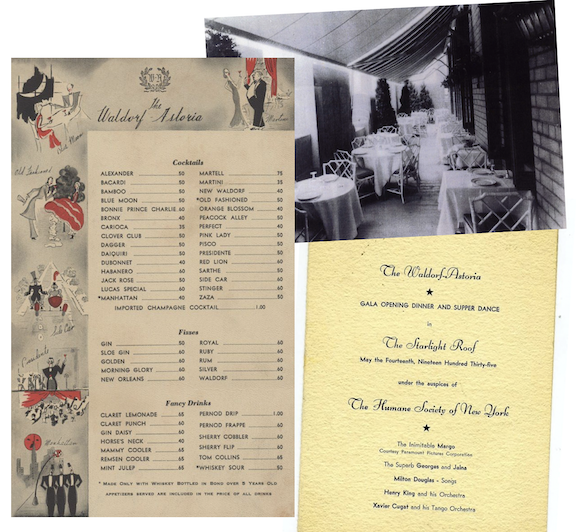

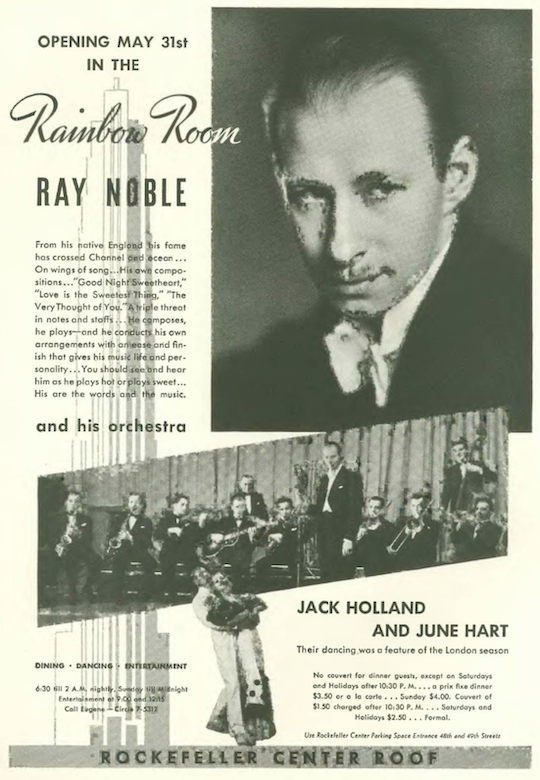

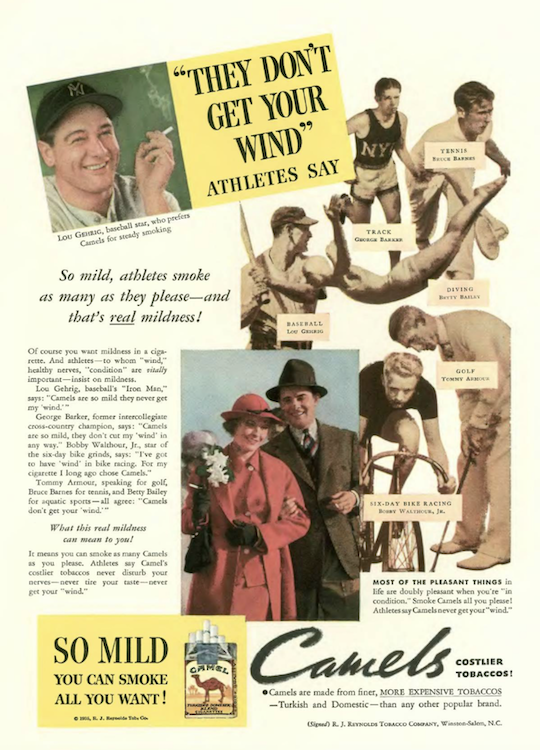

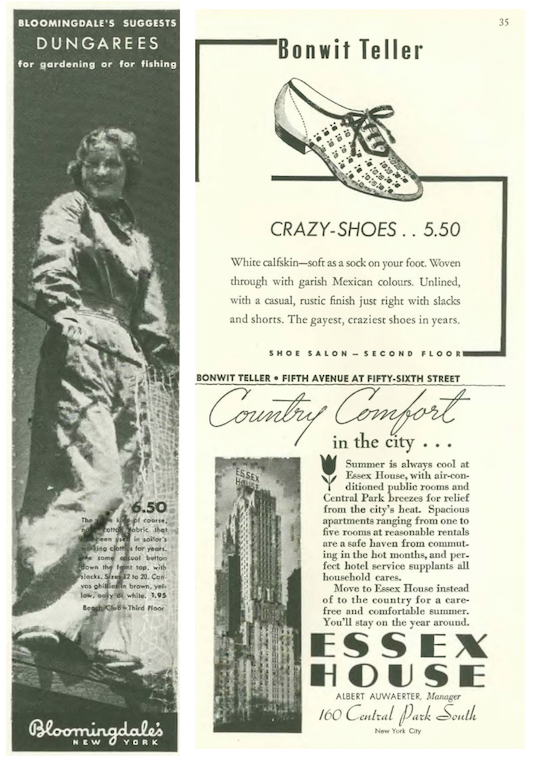

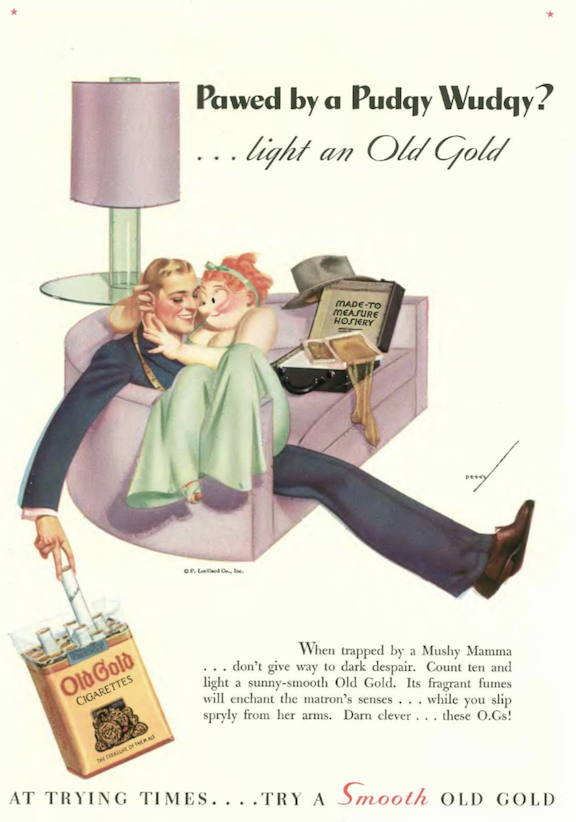

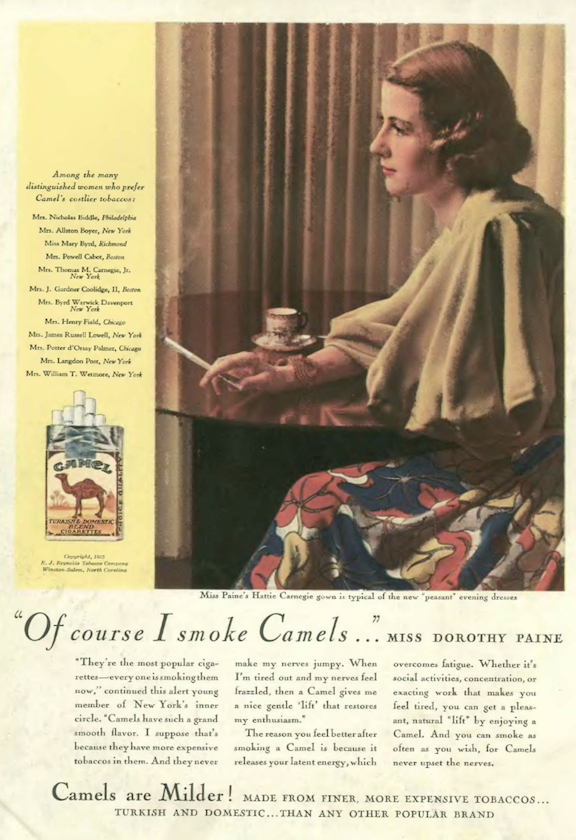

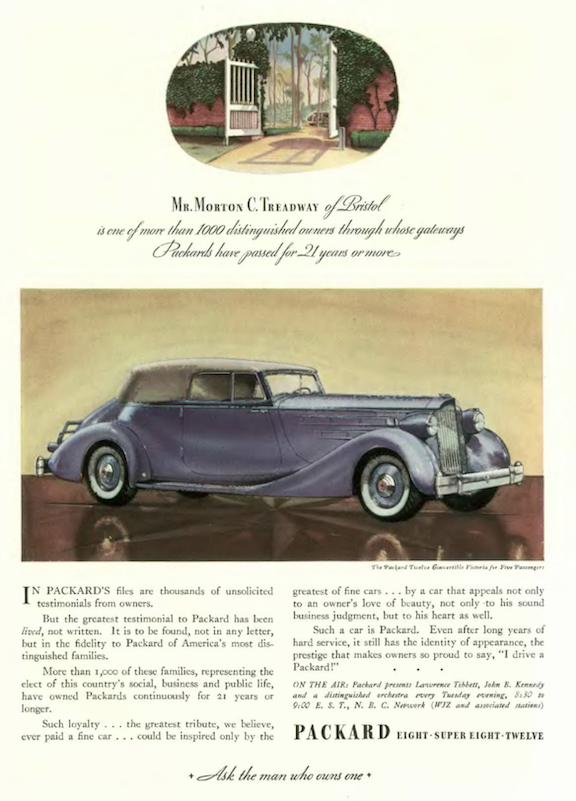

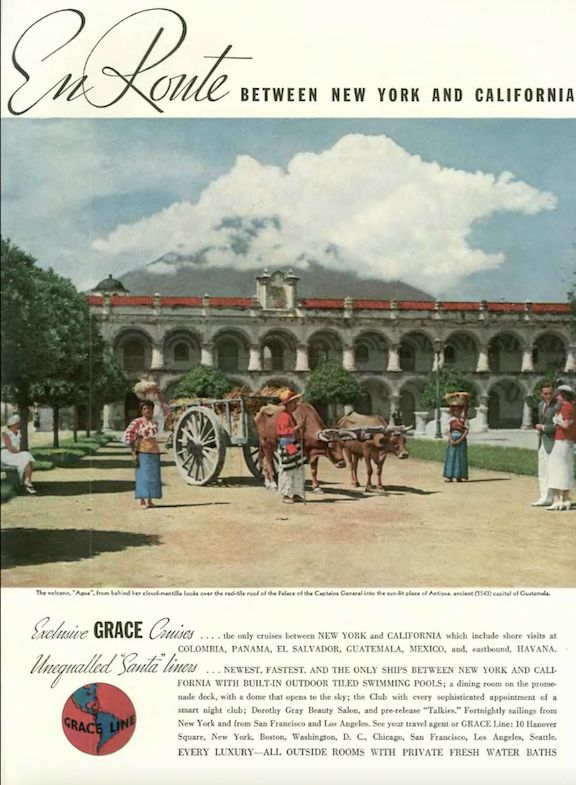

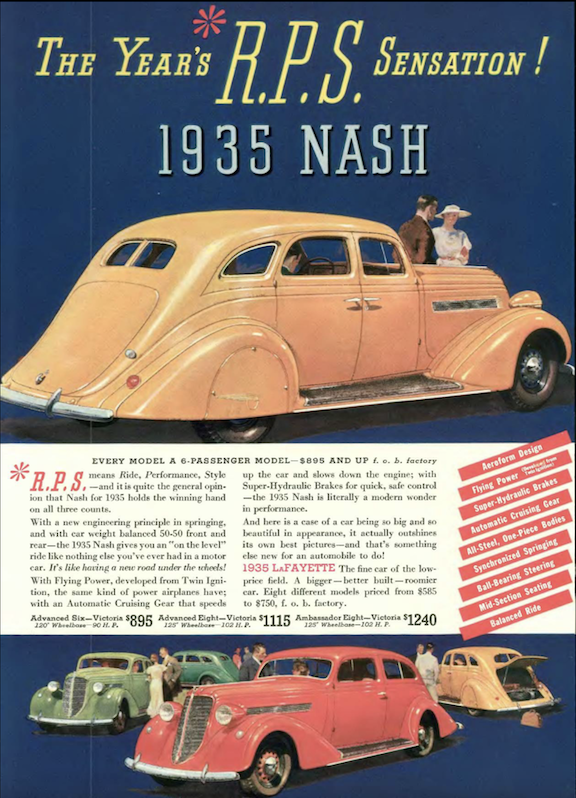

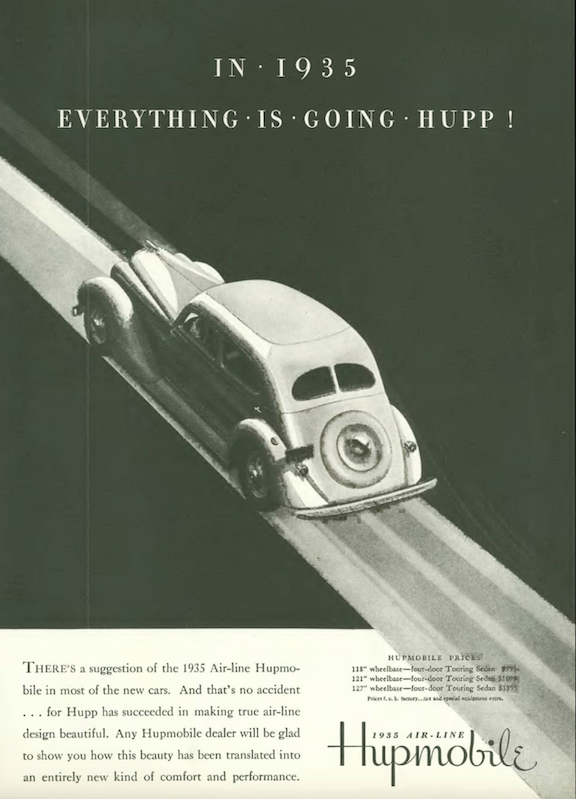

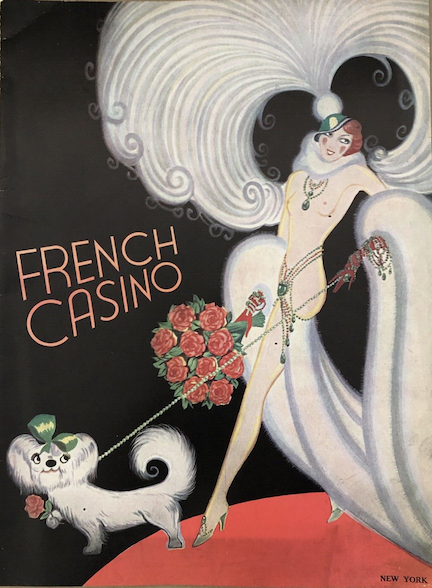

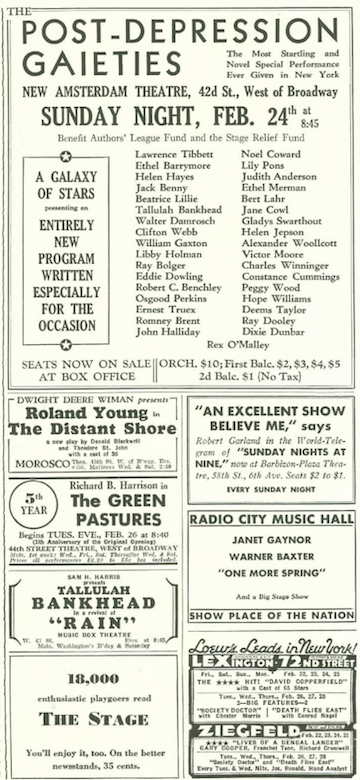

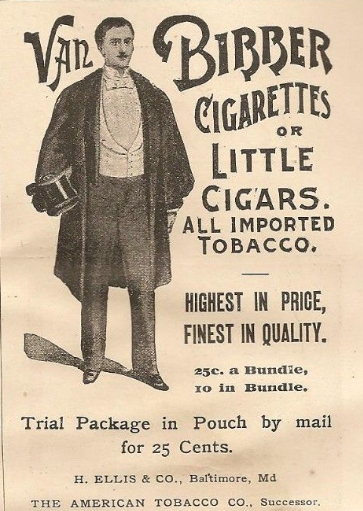

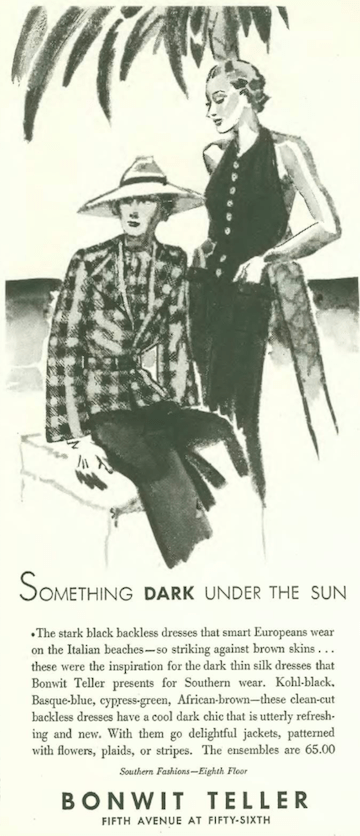

From Our Advertisers

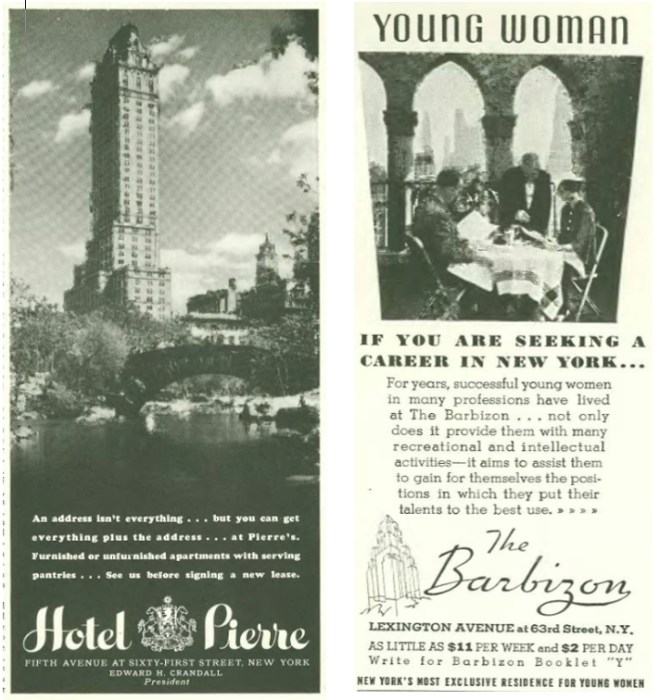

The back of the book was where one could find advertisements for upscale urban living, including these two touting the advantages of the Hotel Pierre and The Barbizon…

…In a joint venture with a group of Wall Street financiers, the former busboy-turned restauranteur Charles Pierre opened the Hotel Pierre in 1930—not the most auspicious time to open a luxury hotel as markets continued to collapse…the Pierre went into bankruptcy in 1932 and was later purchased by oilman J. Paul Getty…the legendary Barbizon Hotel for Women, completed in 1927, was designed as a safe and respectable haven for women seeking to pursue careers in New York, especially in the arts, and would host numerous famous women through the 1970s…

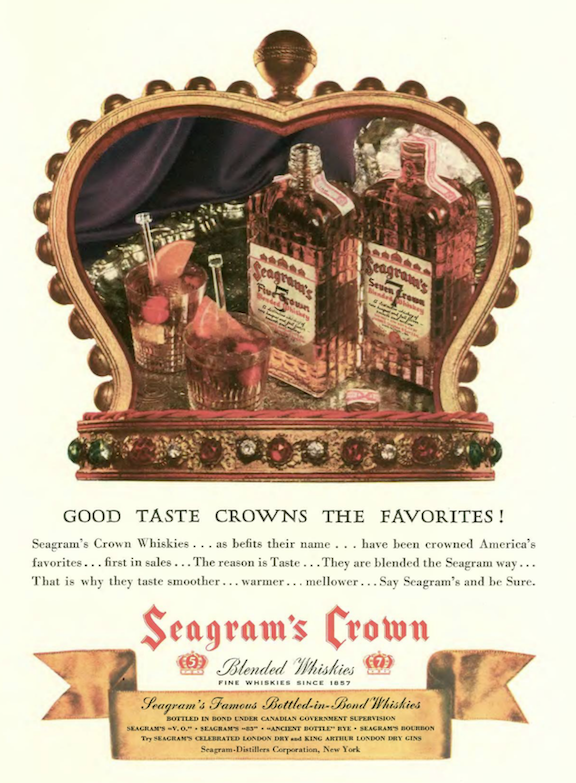

…like the tobacco companies, brewers targeted women as a growth market for a product mostly associated with men…

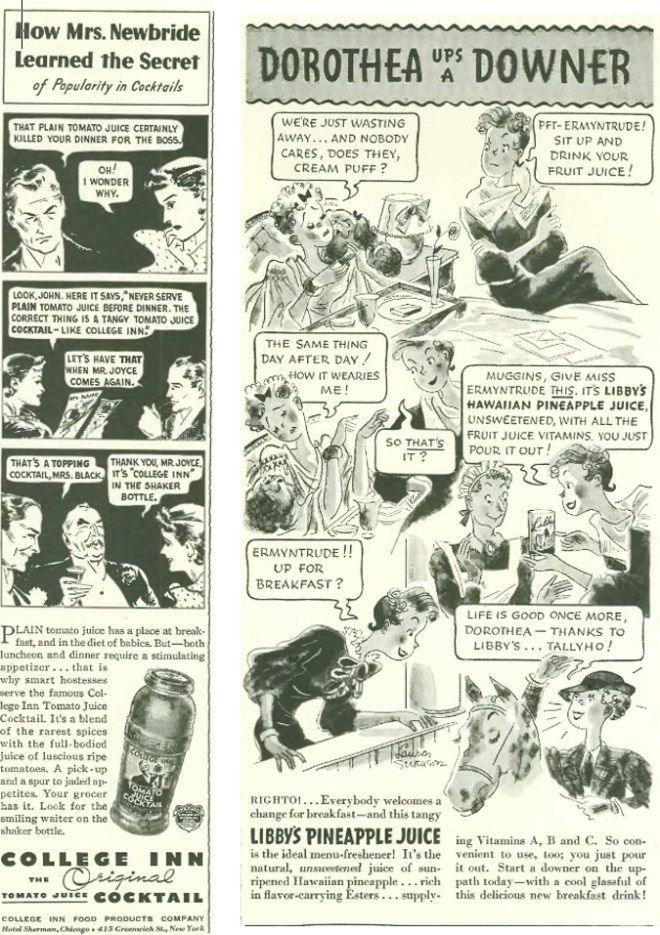

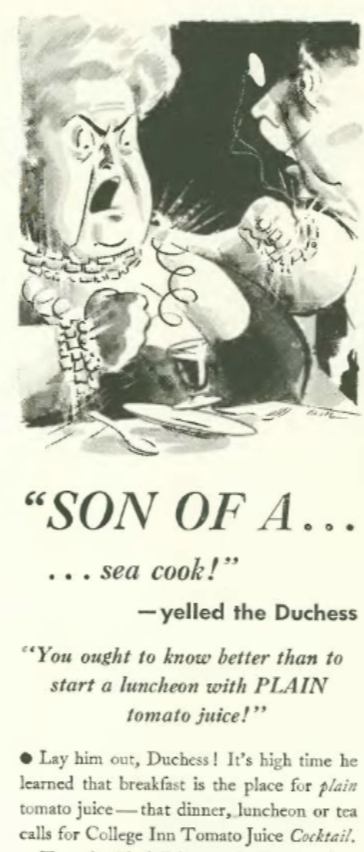

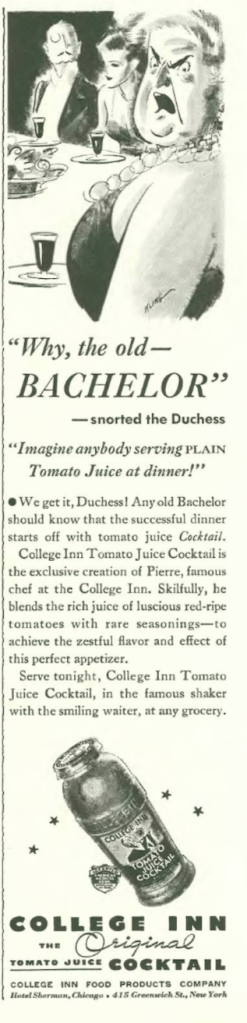

…the makers of juices, meanwhile, created comic strips to promote their products…College Inn still went negative with their ads—recall the violent outbursts of the Duchess…

…here a spiteful husband blames his wife’s choice of tomato juice for his lack of success with the boss…Libby’s, on the other hand, promoted their pineapple juice as a surefire cure for a young woman’s ennui…

…notable in these somewhat thin, late summer issues is the lack of full-color ads…this was on the back inside cover…

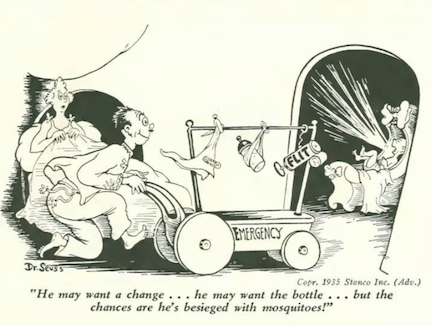

…Flit and Dr. Seuss continued to be a weekly presence…

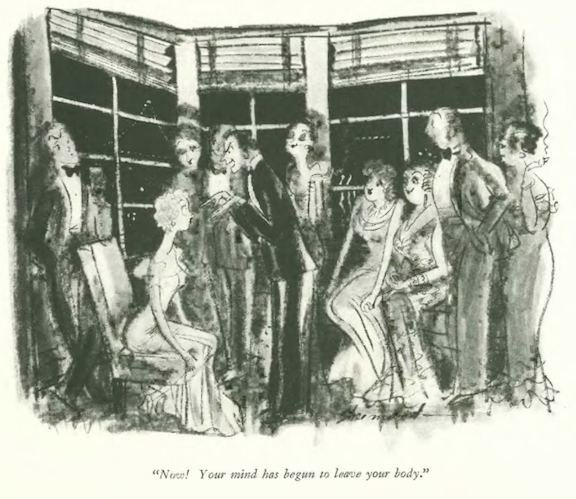

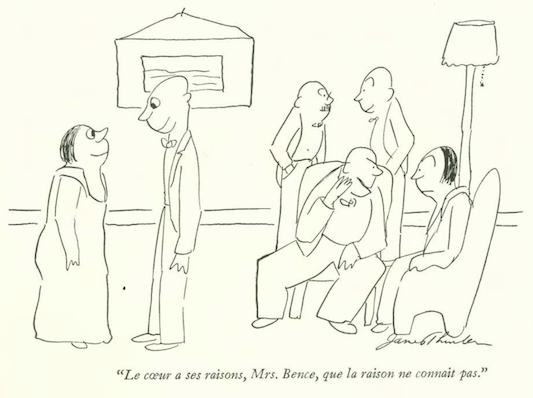

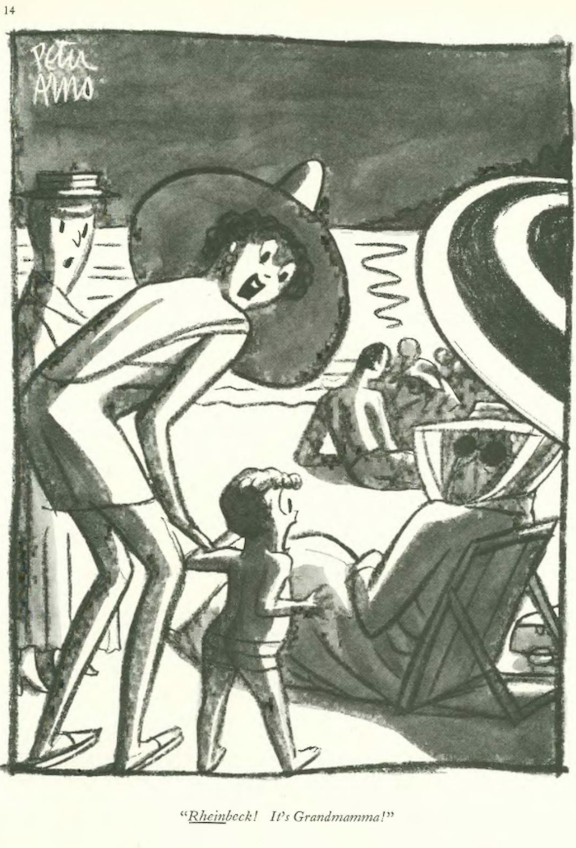

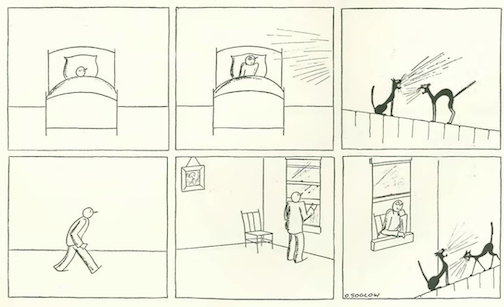

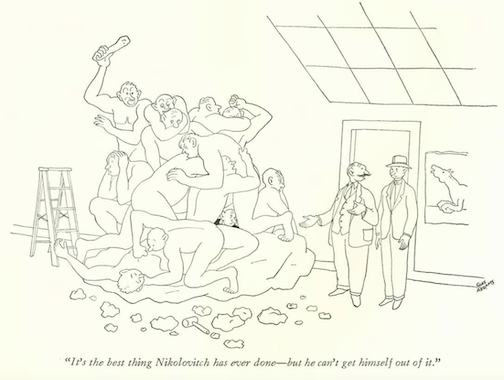

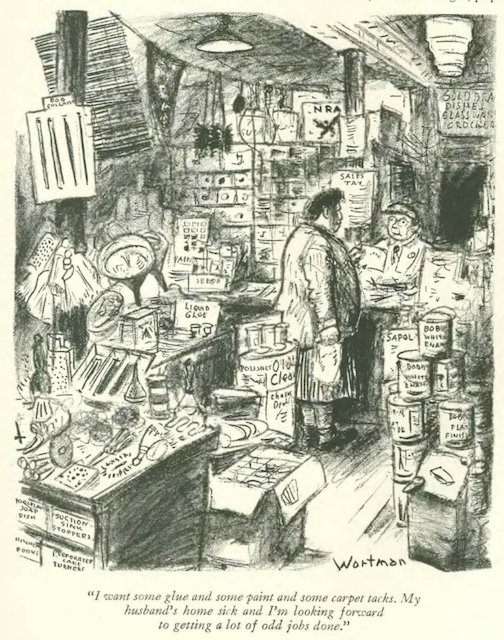

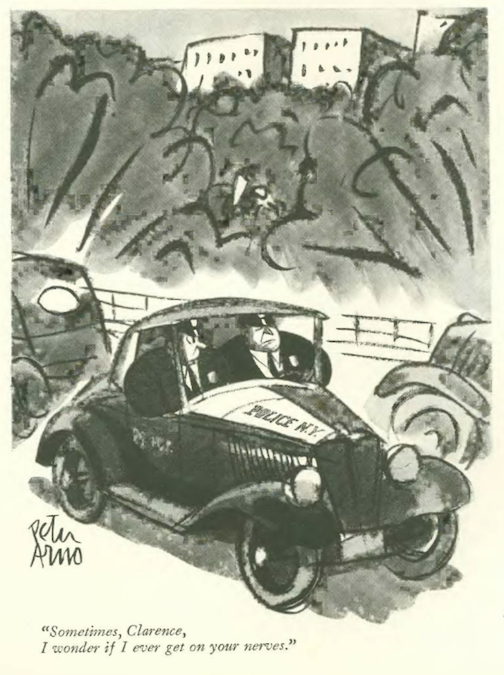

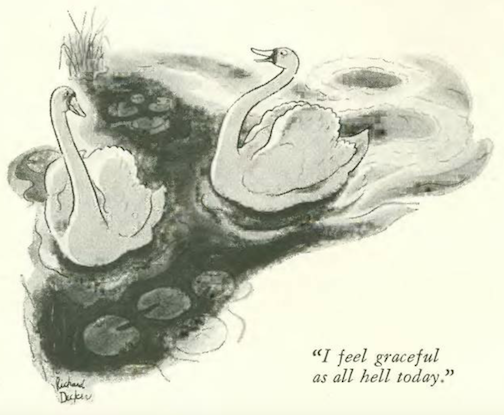

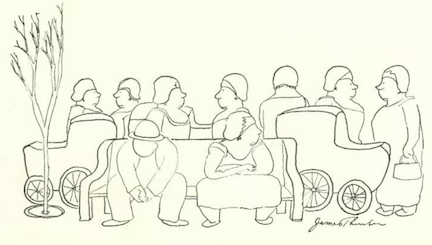

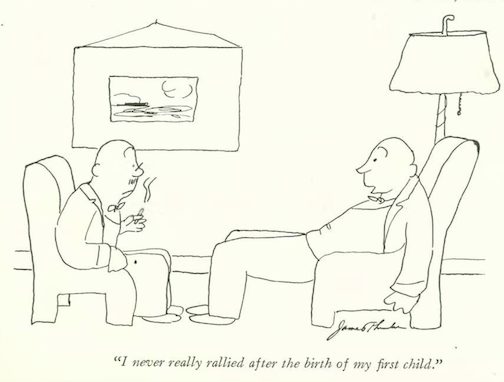

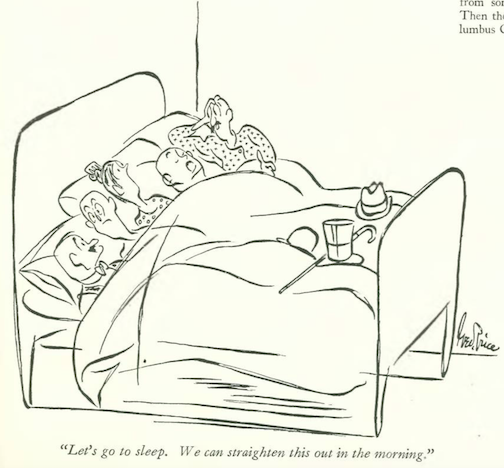

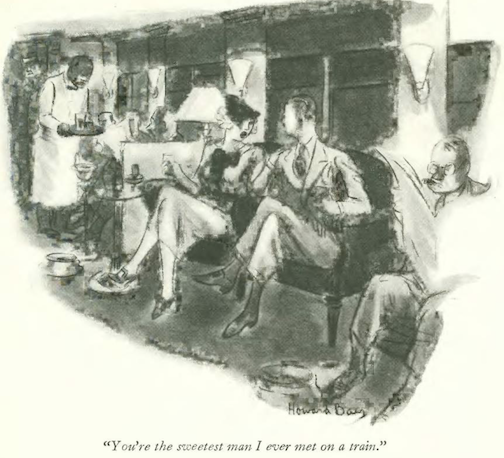

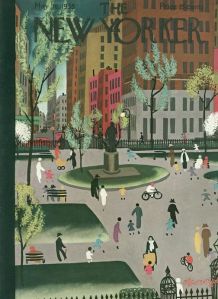

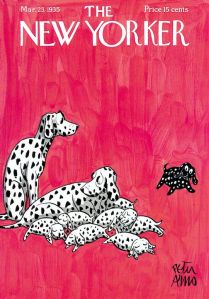

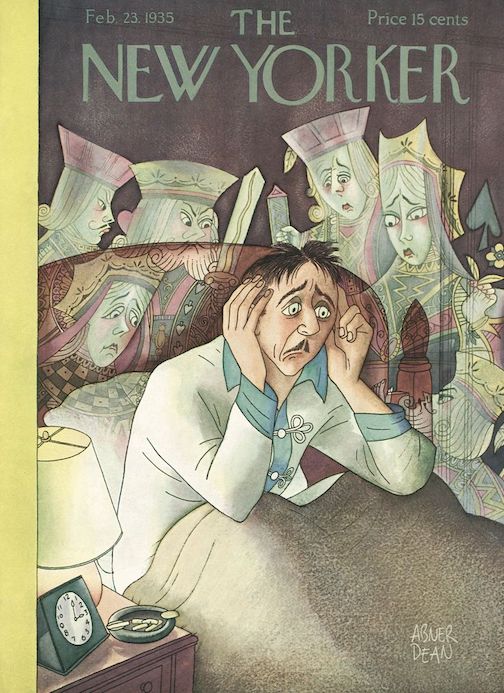

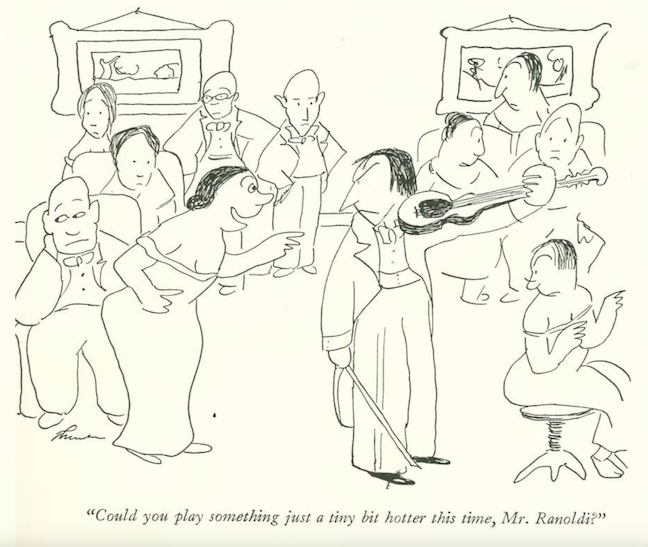

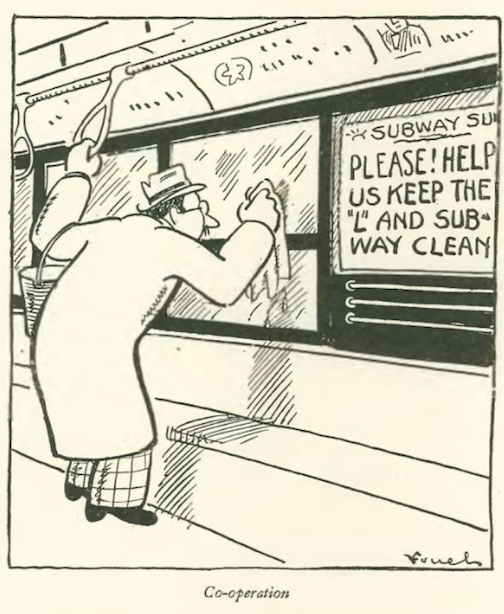

…which brings us to our cartoonists, and a spot drawing by Constantin Alajalov…

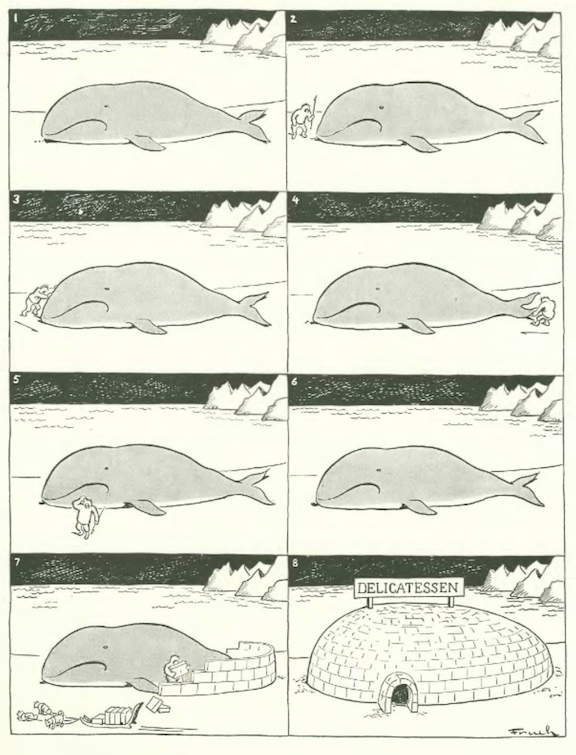

…also a modest spot by Robert Day, keeping us cool with this polar bear…

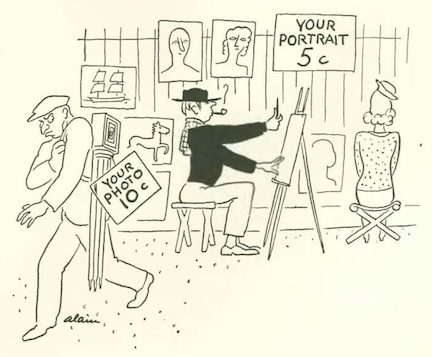

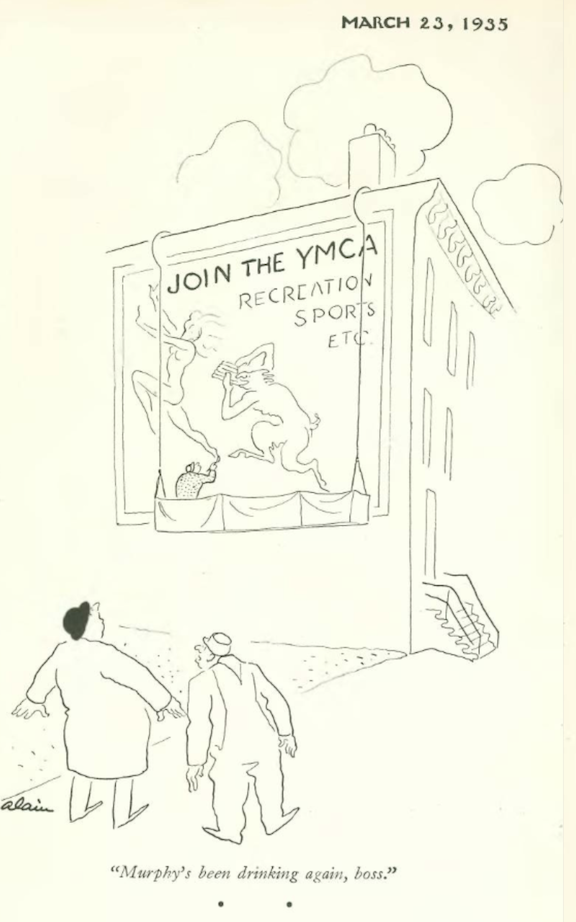

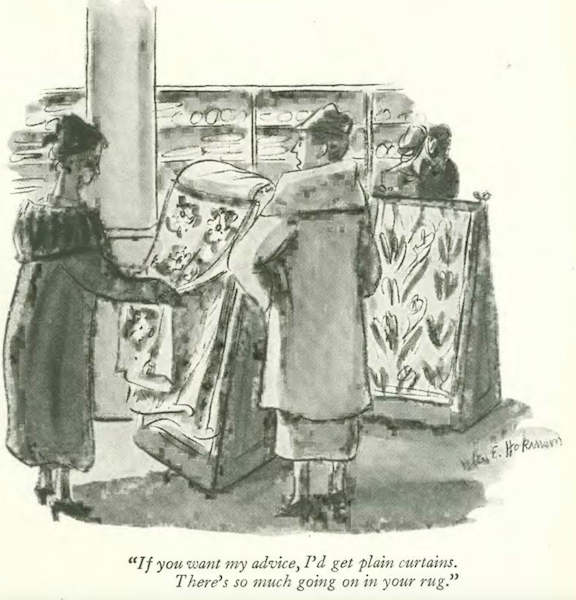

…Alain offered a short course in art appreciation…

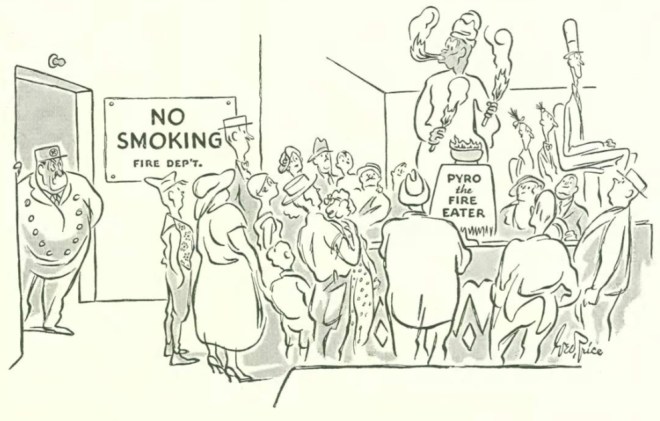

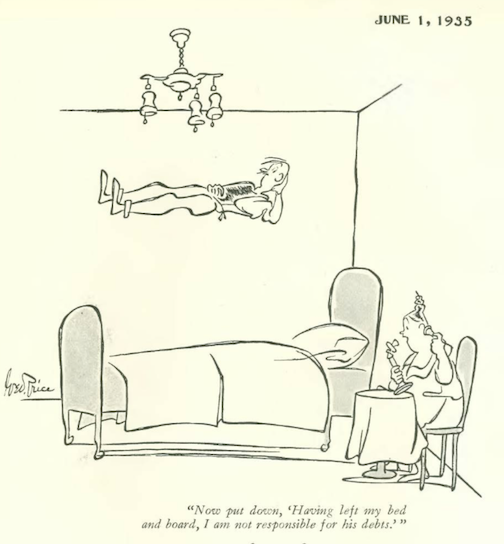

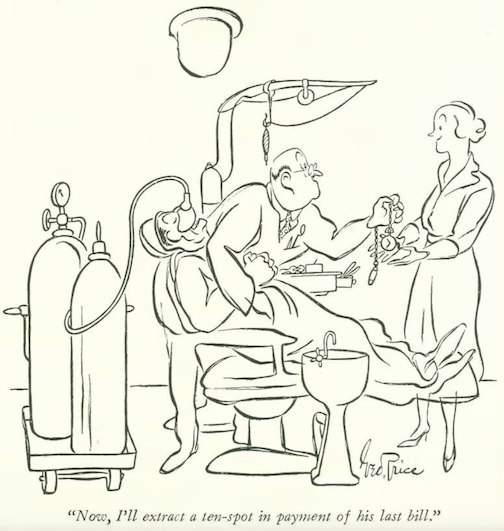

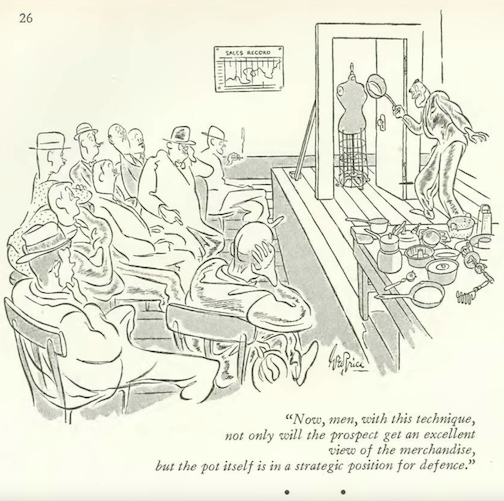

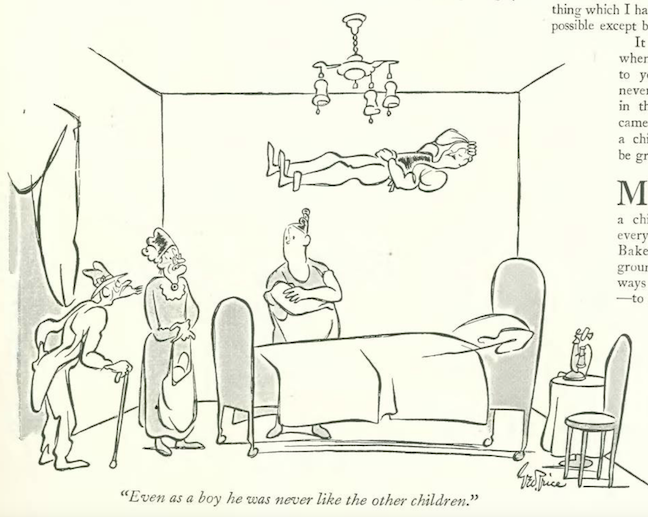

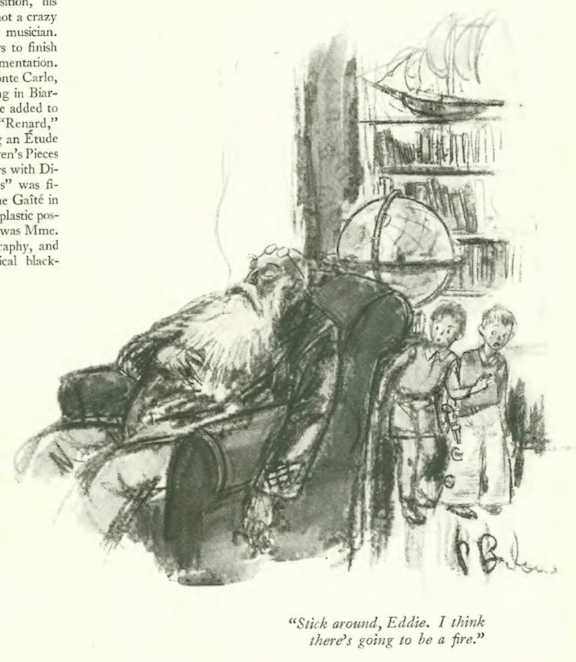

…George Price ran afoul of the fire code…

…Carl Rose ran his tracks across this two-page spread…

…William Steig gave us the small fry’s perspective on the world’s wonders…

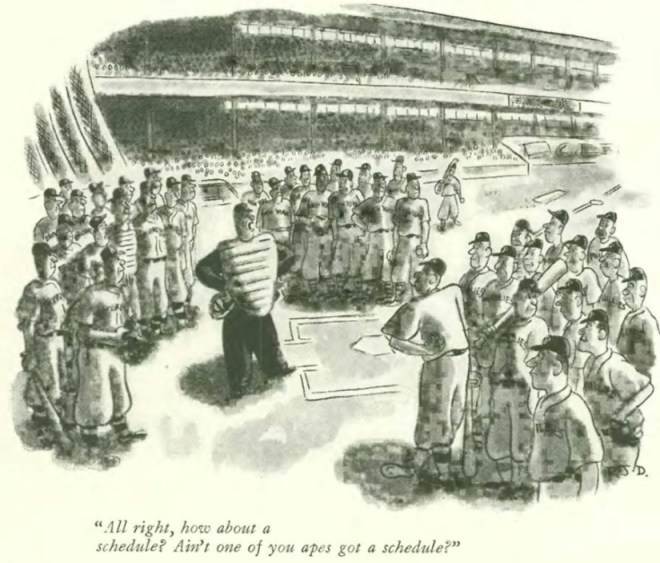

…a rare appearance of baseball in the magazine, thanks to Robert Day...

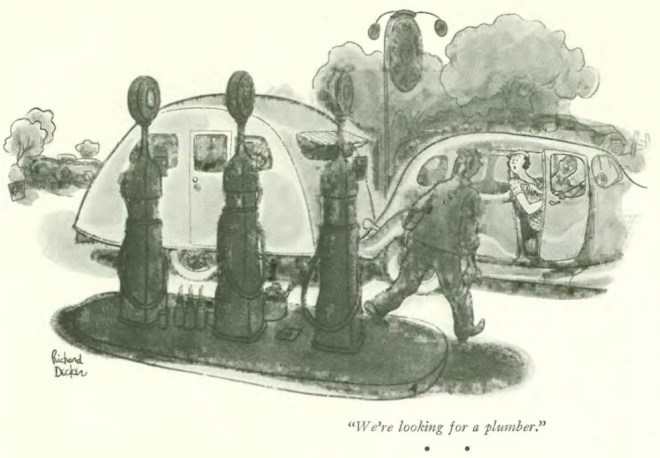

…Richard Decker brought a modern world challenge to one filling station…

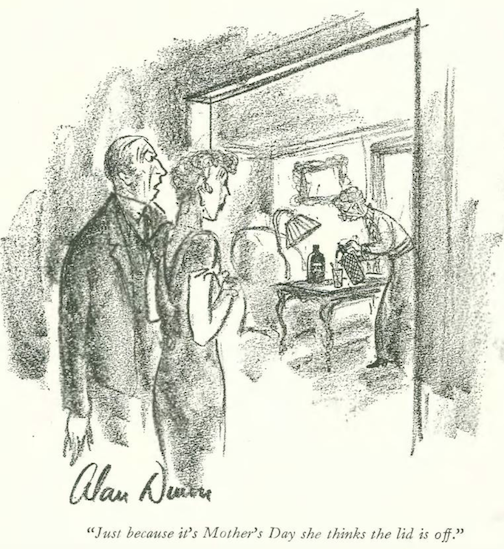

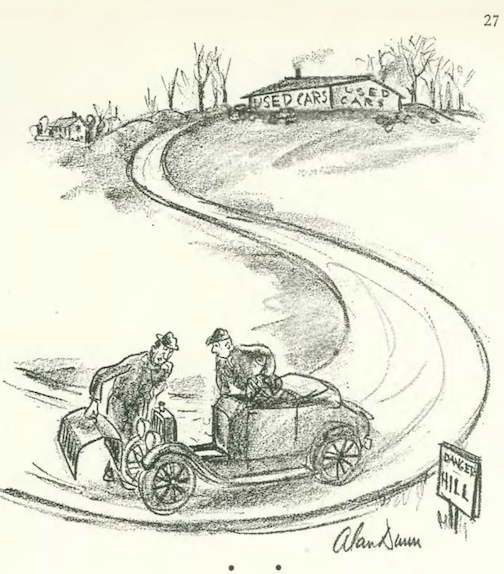

…A sailor’s return to bachelorhood required a new paint job, per Alan Dunn…

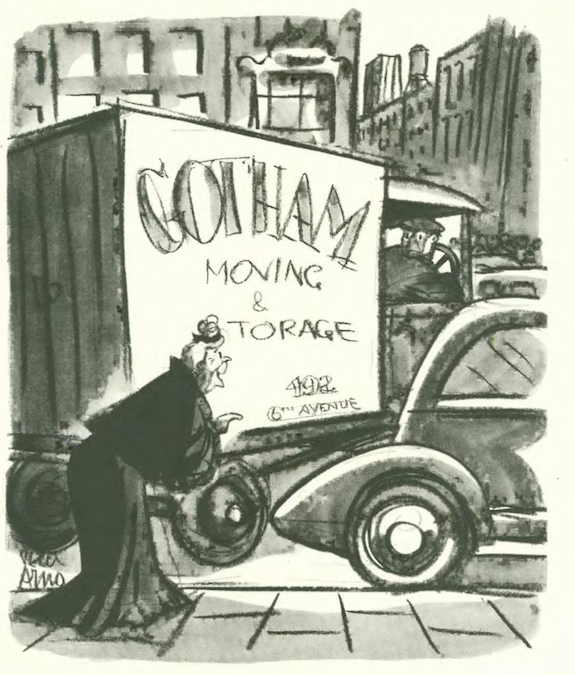

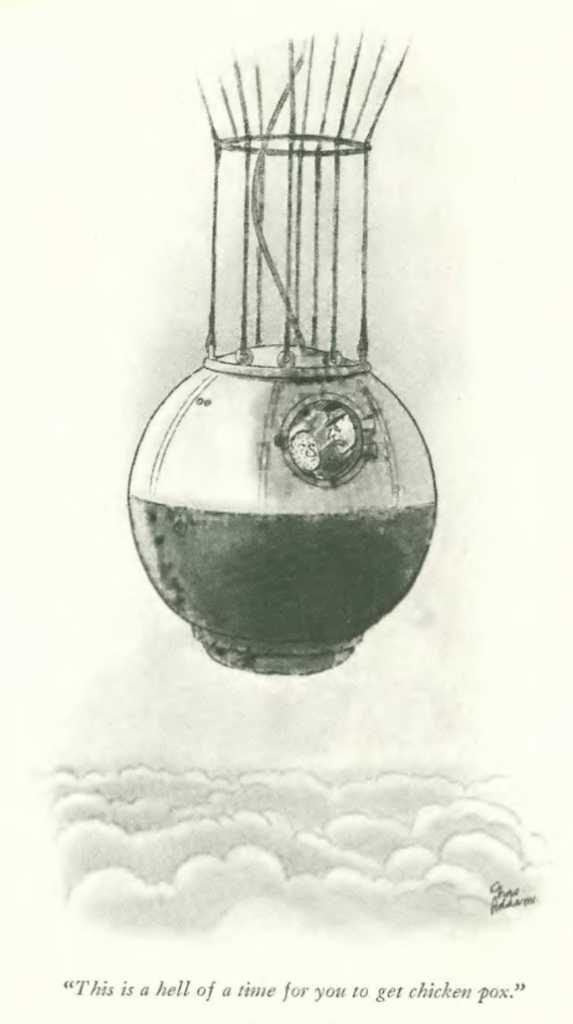

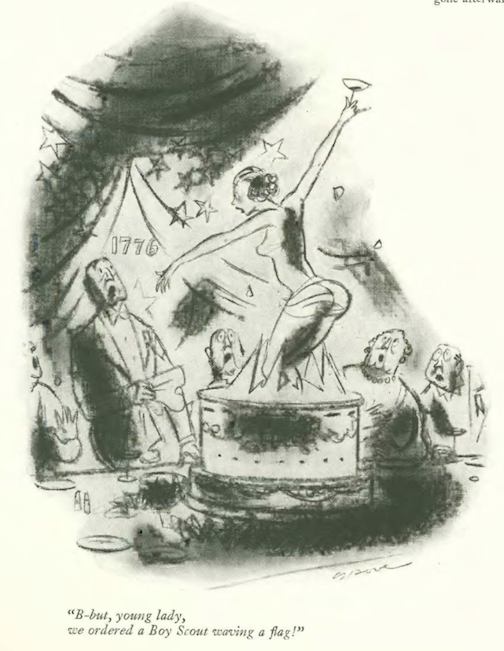

…and who else but Charles Addams would circle vultures over an amusement park?…

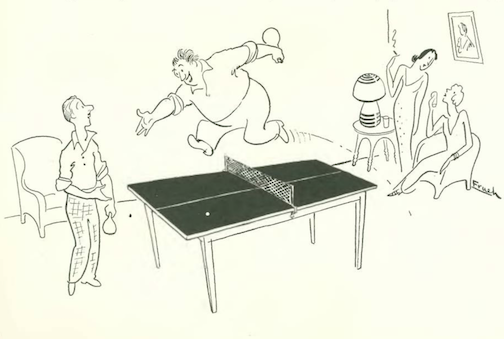

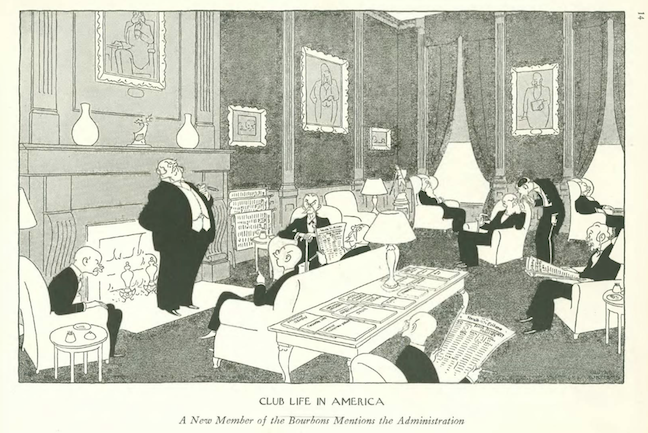

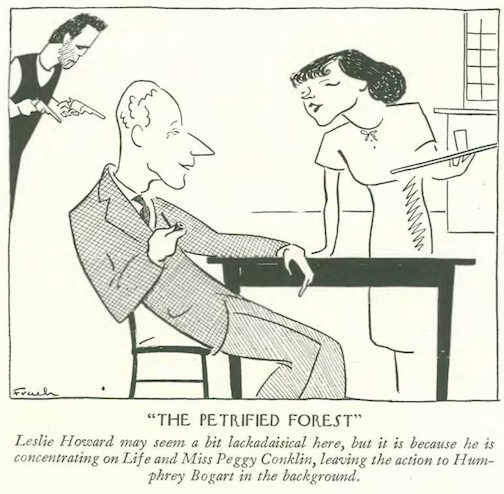

…and we close with Al Frueh, and a Union Club member not concerned with a dress code…

Next Time: The Din and Bustle…