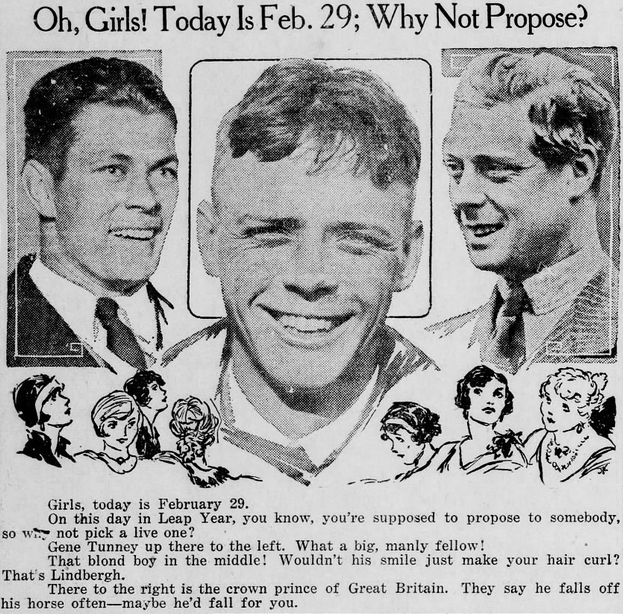

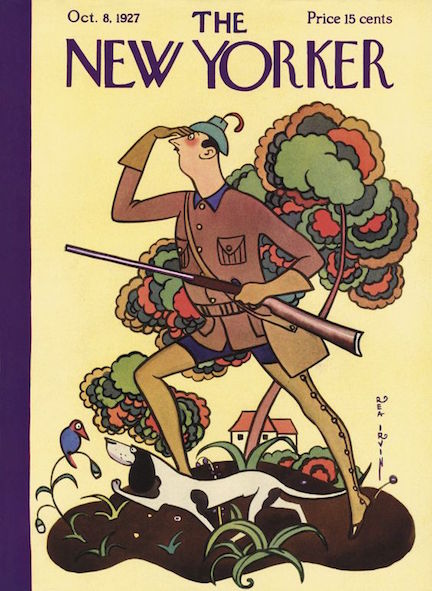

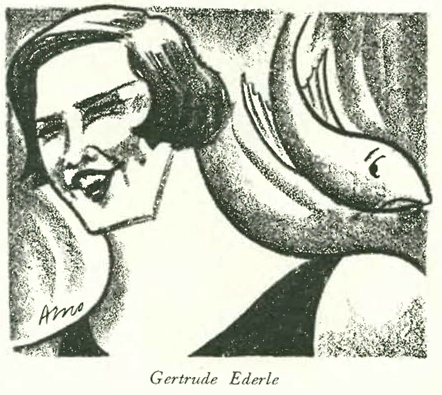

It seems that each generation has its “Fight of the Century,” a phenomenon that emerges from the alchemy of mass marketing, a lust for blood sport, and the madness of crowds. Gene Tunney — a boxer who also wanted to be a public intellectual — was party to at least two of these spectacles in the 1920s.

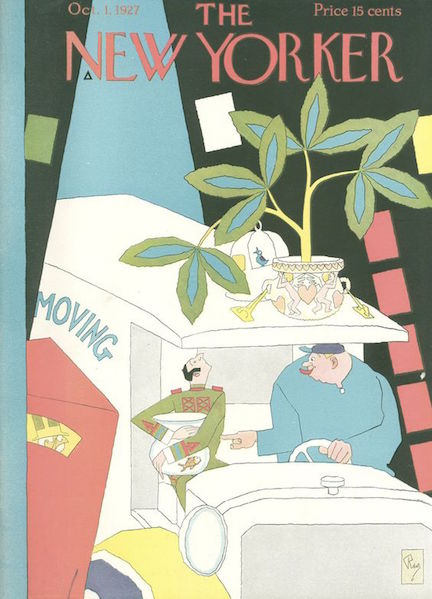

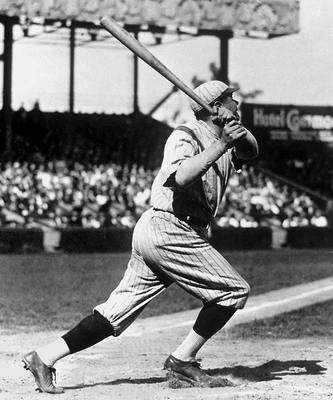

Tunney is most famous for his fights against Jack Dempsey—in some ways they were the Ali–Frazier of their day. Tunney took the heavyweight title from Dempsey in 1926, and again defeated Dempsey in the controversial “long count” rematch one year later, on Sept. 22, 1927. That match was a huge spectacle, staged at Chicago’s Soldier Field in front of 105,000 spectators.

Boxing promoter Tex Rickard saw dollar signs when a scrappy New Zealander named Tom Heeney challenged the champ to a match. Heeney had won the Australian heavyweight title in 1922, and after arriving in the U.S. in 1926 found enough success in the ring to be ranked fourth among the world’s heavyweight boxers.

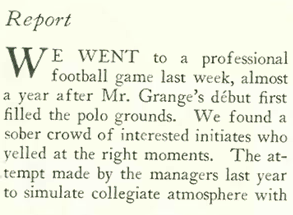

Writing in his column, “Sports of the Week,” in the July 21, 1928 issue of The New Yorker, Niven Busch Jr. assessed Heeney as a formidable opponent:

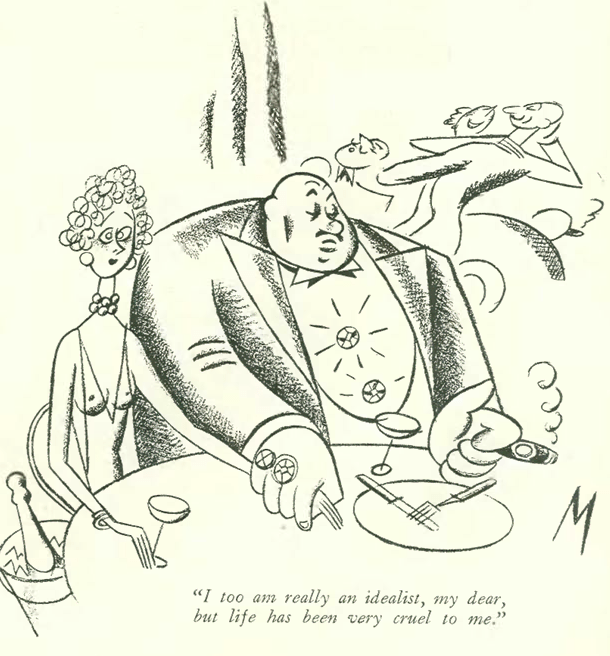

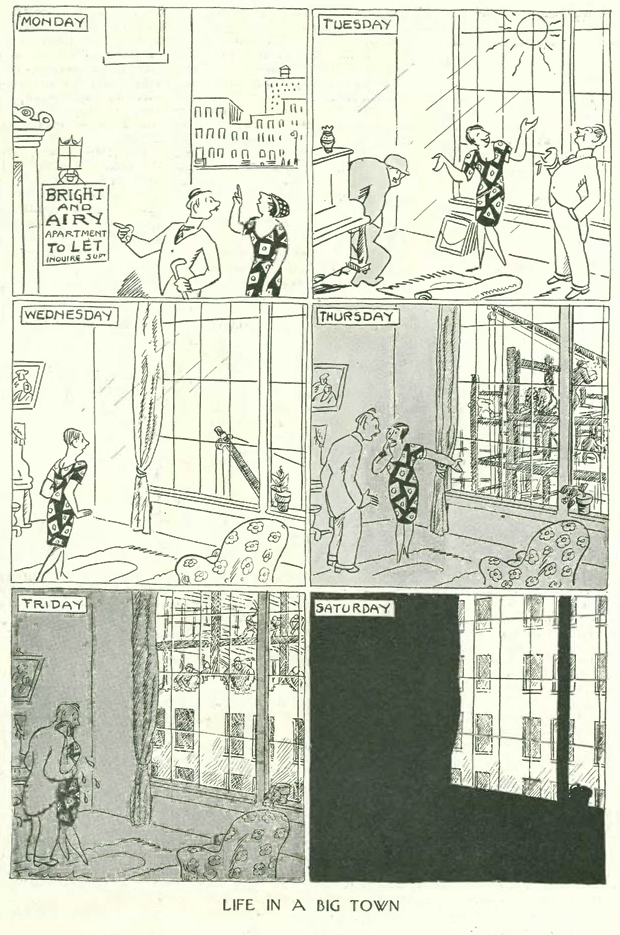

This cartoon by Leonard Dove, also in the July 21 issue, joined in the fun…

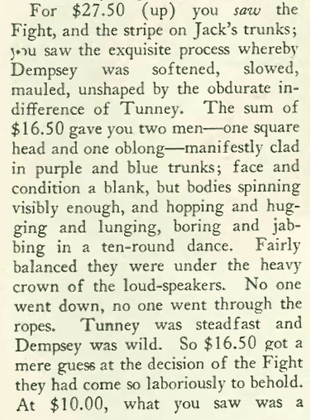

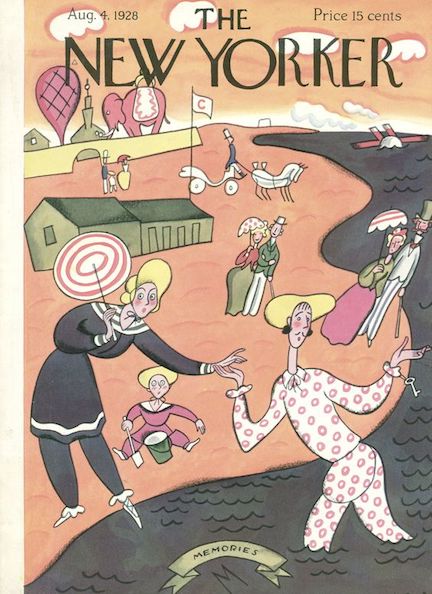

As for the actual fight at Yankee Stadium on July 26, 1928, Tunney won by a TKO in the 11th round. Perhaps the boxer from Down Under wasn’t in such great shape after all, or so surmised Niven Busch Jr in the August 4 issue:

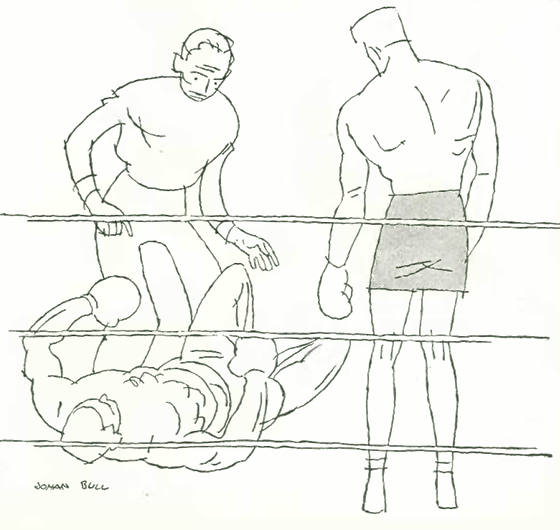

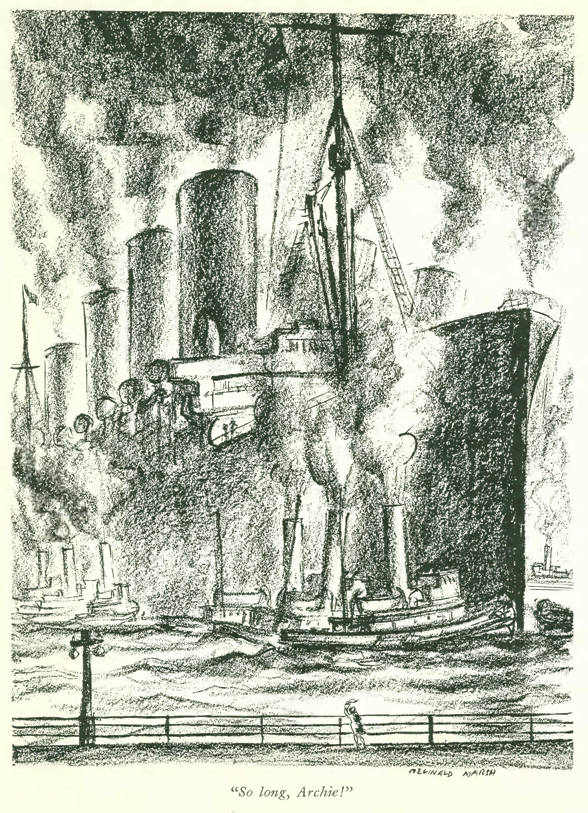

New Yorker illustrator Johan Bull offered this perspective in artwork that accompanied Busch’s article…

Tunney’s winning purse was $525,000 (about $7.3 million today) and Heeney’s was $100,000 ($1.4 million), modest when compared to the recent debacle in Las Vegas that pitted professional boxer Floyd Mayweather Jr. against mixed martial arts champion Conor McGregor. Mayweather earned a disclosed purse of $100 million while Conor McGregor brought home $30 million.

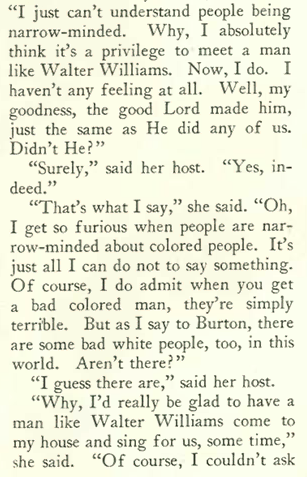

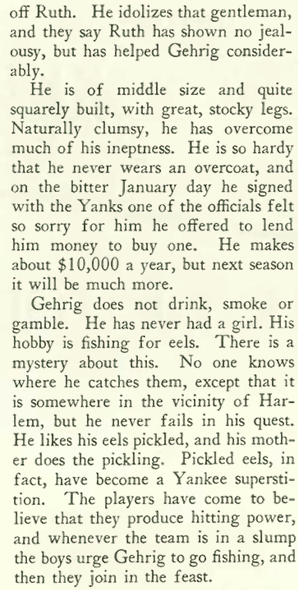

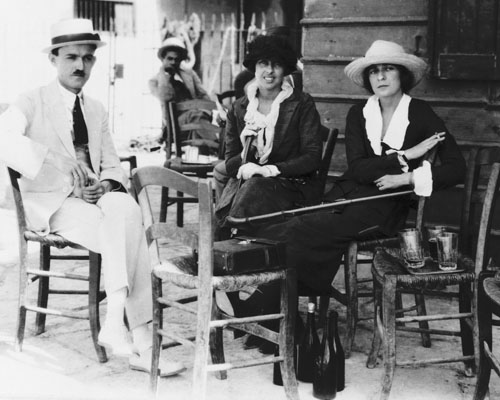

Heeney would remain in the U.S. and fight a few more bouts before retiring to Florida, where he ran a bar and fished with his friend, Ernest Hemingway. Tunney, on the other hand, announced his retirement from boxing just five days after the fight. It was time to finally devote himself to a life of the mind. Norman Klein, writing in the Aug. 4 “Talk of Town,” offered a glimpse into that new life:

Still not getting enough of The Champ, “Talk” also related this story about Lucky Strike cigarettes, and how that company’s publicists tried unsuccessfully to persuade Tunney to endorse their product:

However the promoter of the Tunney–Heeney fight, Tex Rickard, had no problem taking money from the American Tobacco Company:

* * *

Tunney Was More Exciting

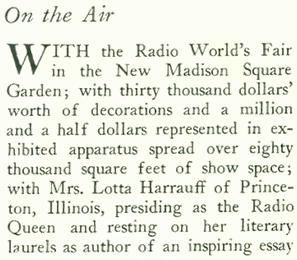

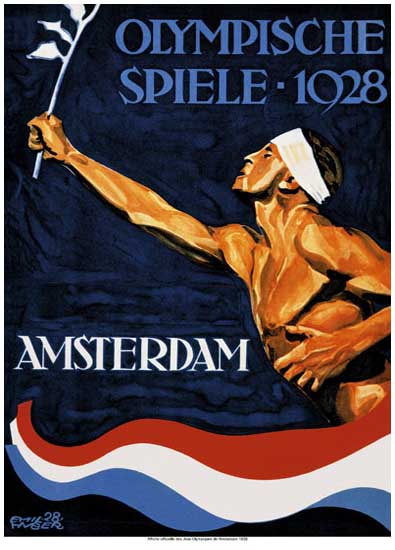

“The Talk of the Town” cast a jaded eye toward the Ninth Olympic Games in Amsterdam:

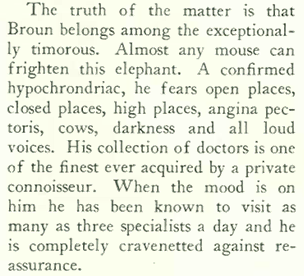

And perhaps even less exciting than the Olympics was the magazine’s “Profile” subject, Andrew W. Mellon, referred to in the title as “Croesus in Politics.” Mellon was no Gene Tunney, but he did ensure his immortal fame through his philanthropy, still expressed today by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Below are the concluding lines of the profile, written by Homer Joseph Dodge:

The article featured this terrific caricature by illustrator Abe Birnbaum…

Planned Obsolescence

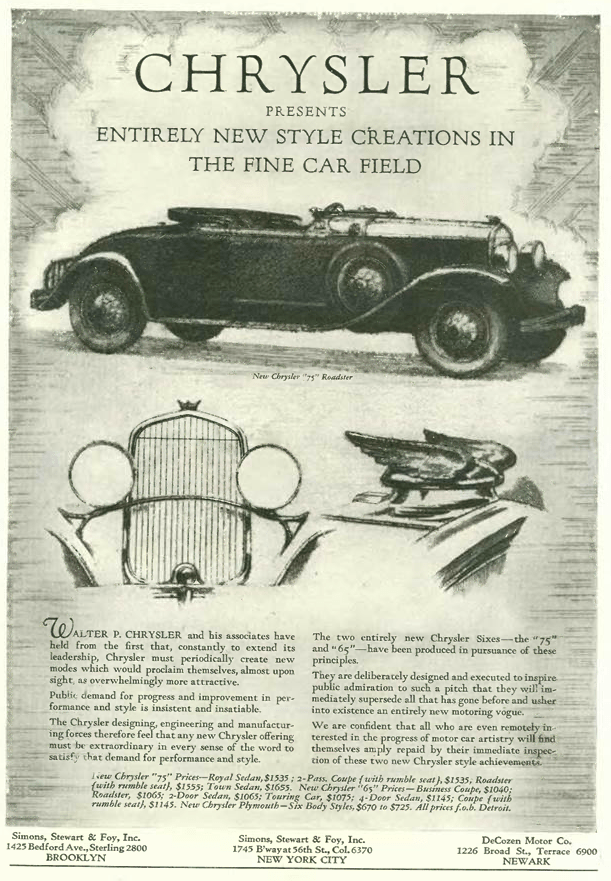

The magazine’s “Motors” column touted Chrysler’s new “peaked” radiators, which no doubt caused many insecure Chrysler owners to consider junking their non-peaked models of yesteryear:

This ad in the same issue screamed “new, new, new” for what appeared to be mostly the same old, same old…

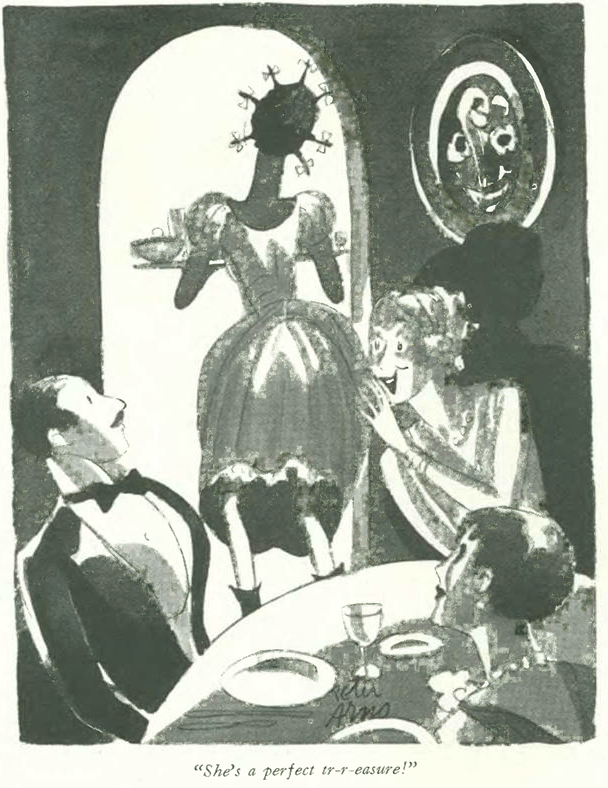

Our comic comes courtesy Al Frueh, who looks in on the workings of a printing press at a celebrity tabloid:

Next Time: Shadows of the South Seas…