Above: Actress Gloria Swanson amid the ruins of the Roxy, 1960. The famed theater opened with Swanson's silent film, "The Love of Sunya."(Time Inc.)

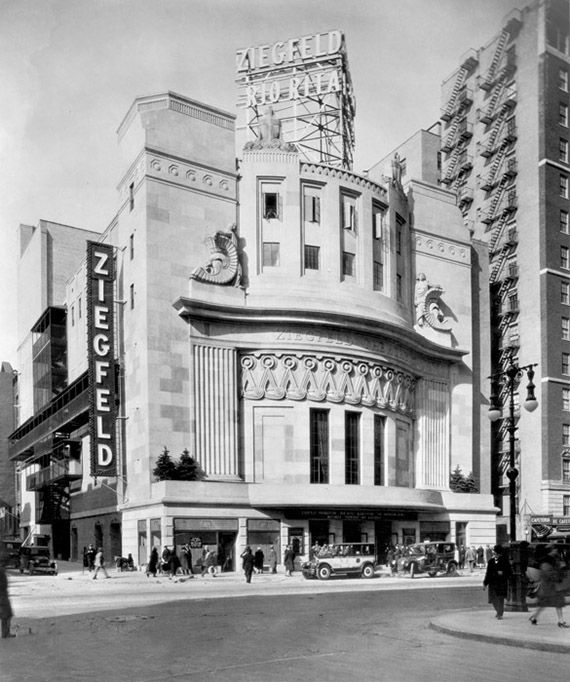

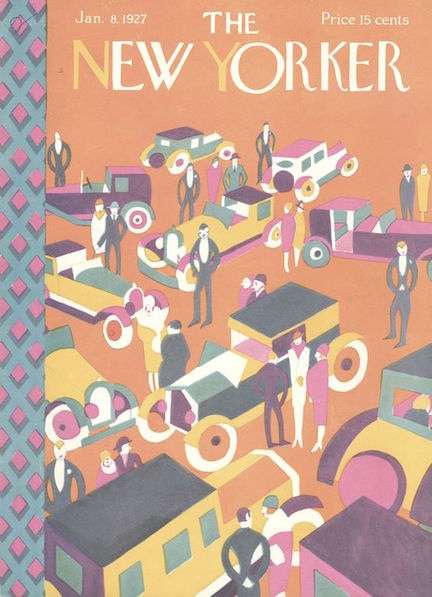

Jazz Age New York City was all about the big and grand, and nothing was bigger and grander than the new Roxy Theatre near Times Square.

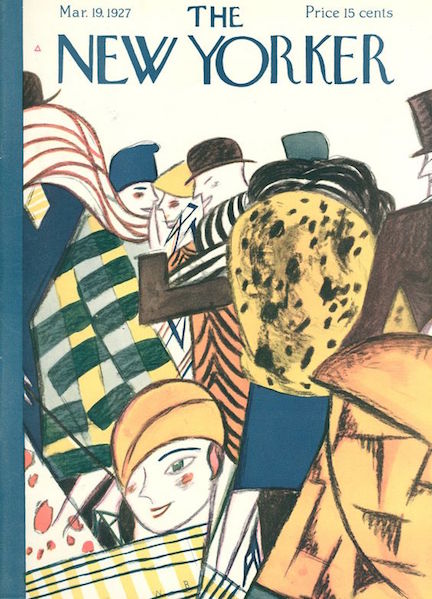

The nearly 6,000-seat theatre was such big news that the March 19, 1927 edition of The New Yorker heralded its arrival in three separate columns.

The Roxy opened with the silent film The Love of Sunya, produced by and starring Gloria Swanson. The film, naturally, was panned by the magazine. Perhaps the critic’s distaste for the film also prompted a certain aloofness about the theatre itself:

“The Talk of the Town” described the Roxy in similar dispassionate terms, tossing a wet blanket not on the film but rather on the rude, gawking masses who shelled out eleven bucks apiece (equivalent to $150 today) for a seat on opening night:

New Yorker architecture critic George S. Chappell (aka “T-Square”) was a bit more generous in his column, “The Sky Line.”

* * *

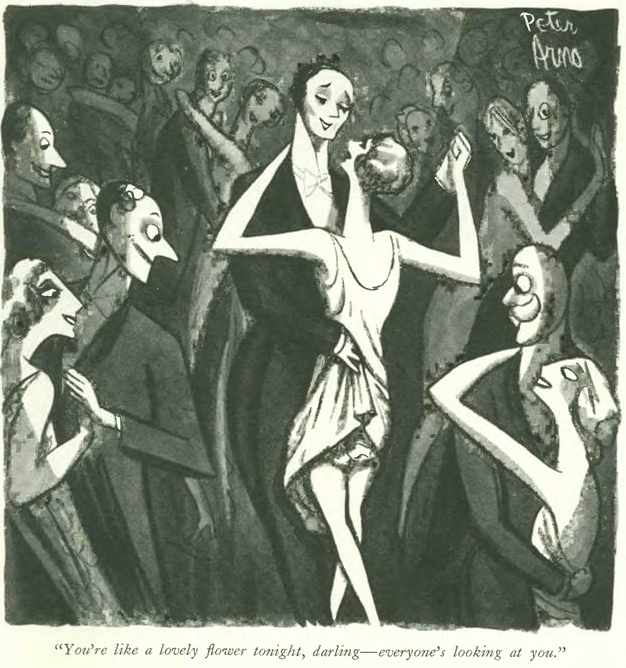

The magazine took an unusual approach to its “Profile” section by featuring an autobiographical profile of poet Elinor Wylie in verse, a portion of which is shown below with an illustration by Peter Arno:

* * *

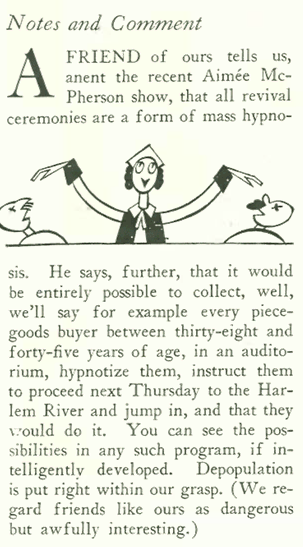

Morality-themed books got the attention of New Yorker book reviewer Ernest Boyd (pen name “Alceste), who devoted considerable ink to Anthony Comstock: Roundsman of the Lord by Heywood Broun and Margaret Leech (both of Algonquin Round Table fame). Comstock was a United States Postal Inspector and politician known for the “Comstock Law,” which sought to censor materials he considered indecent and obscene. That included birth control information, which led to famous clashes between Comstock and family planning advocate Margaret Sanger.

An advertisement for the book appeared in the back pages of the magazine:

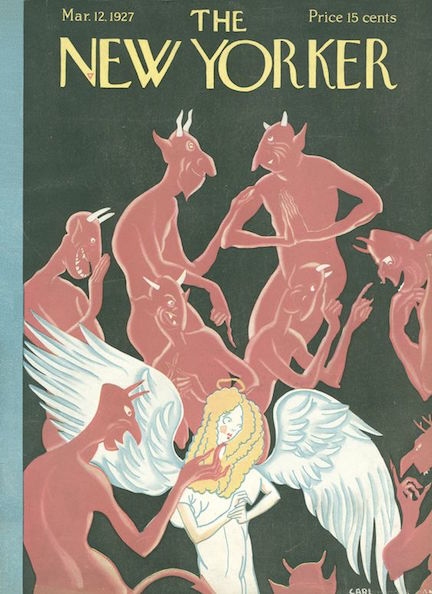

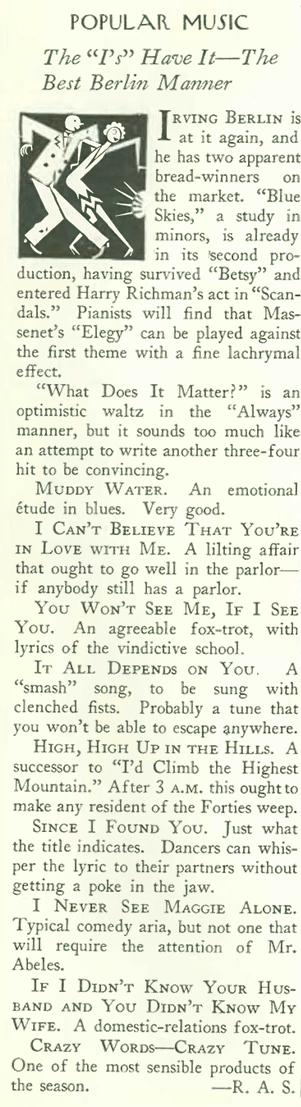

Boyd also reviewed Sinclair Lewis’s Elmer Gantry, a controversial novel that exposed the hypocrisy of some 1920s evangelical preachers:

* * *

This advertisement began to appear in the pages of the New Yorker for a new restaurant that claimed to replace the beloved Delmonico’s. Despite its status as a New York institution, Delmonico’s had fallen victim to the changing dining habits of Prohibition New York and had closed its doors in 1923:

The restaurant was operated by the Happiness Candy Stores chain, which according to the ad also operated restaurants in two other locations in the city. The restaurants must have been short-lived, as I could find no record of them apart from the ads.

Next Time: The Garden City…