Lux Toilet Soap was launched in the United States in 1925 by its British parent company, Lever Brothers, which had been making soap since 1899. To capture the hearts and pocketbooks of American women, the company launched an advertising blitz that featured advertisements in a number of magazines including The New Yorker.

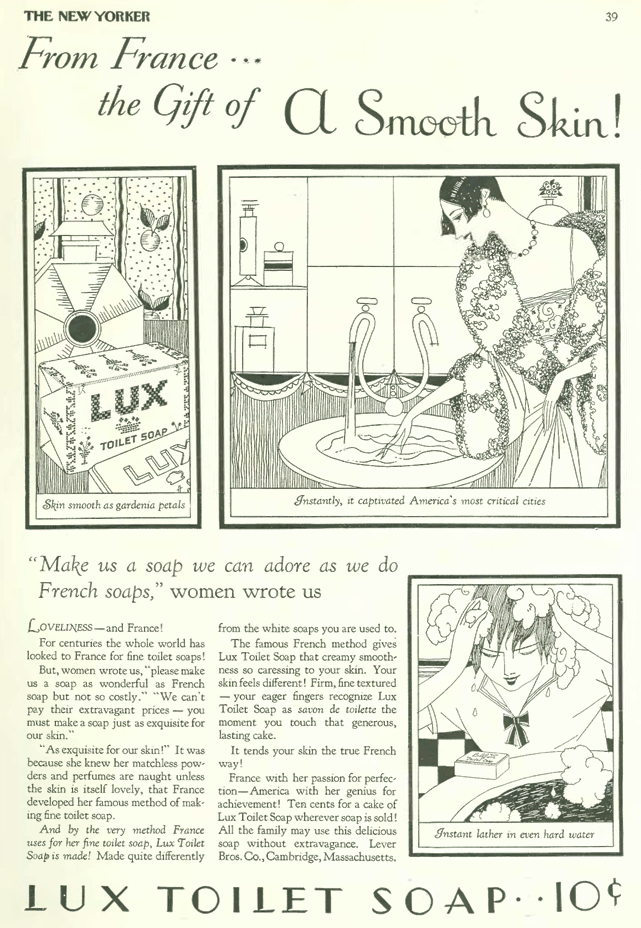

The earliest ads appealed to upscale women who saw the French as arbiters of taste and style. In the following Lux ad (from the Feb. 5, 1927 New Yorker), note that every paragraph and headline includes the words France or French:

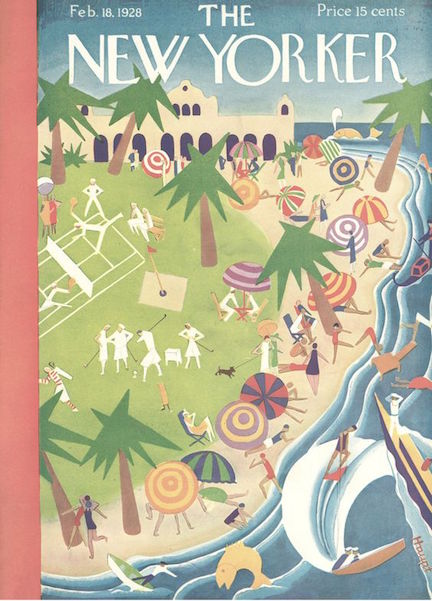

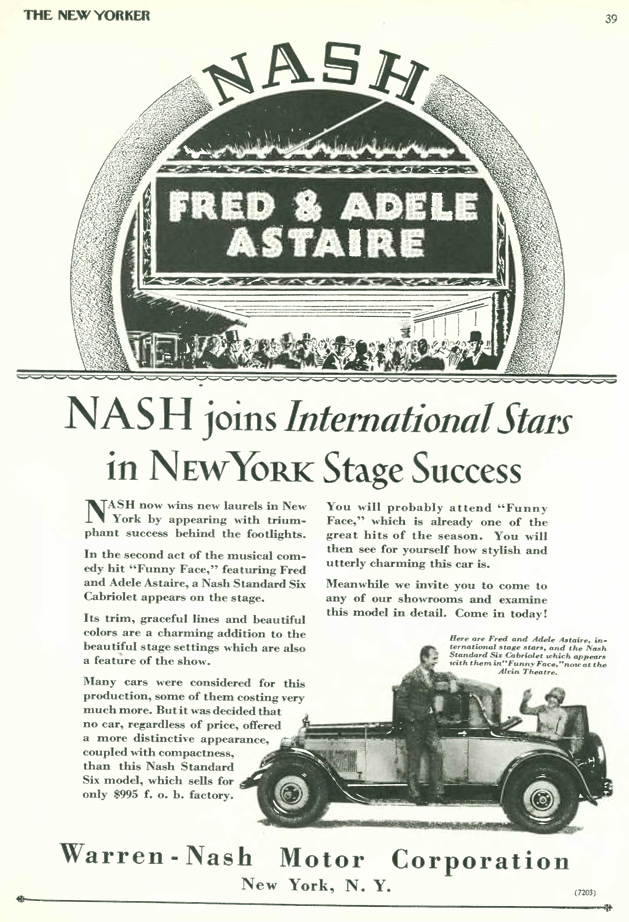

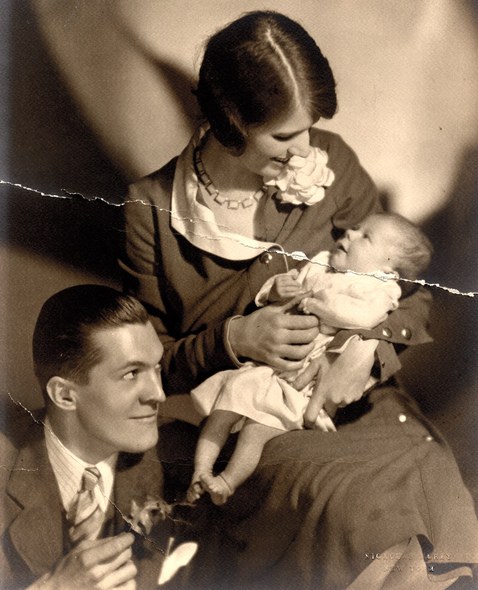

The big blitz came in 1928, when Lux pioneered the use of female celebrity endorsements on a mass scale. The campaign focused more on the roles played by Broadway and movie stars than on the product itself. The March 24, 1928 issue of The New Yorker featured these ads splashed across two center spreads.

The captions I have provided below the ads give brief information on each actress. Note that many of these actresses did stints with Broadway’s popular Ziegfeld Follies. Most also had long lives, including Mary Ellis, who lived in three centuries, sang with Enrico Caruso, and died at age 105.

Click Images to Enlarge

Over the years dozens of famous actresses would appear in colorful ads singing the praises of Lux soap…

A final note. Lever Brothers began selling Lux soap in India in 1909, years before it was introduced in the U.S., and through the decades Bollywood actresses were prominently featured in their advertising…

* * *

Meanwhile, back on earth…

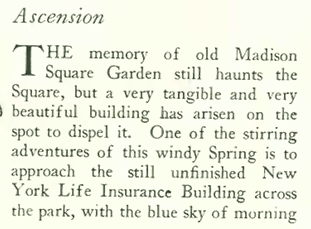

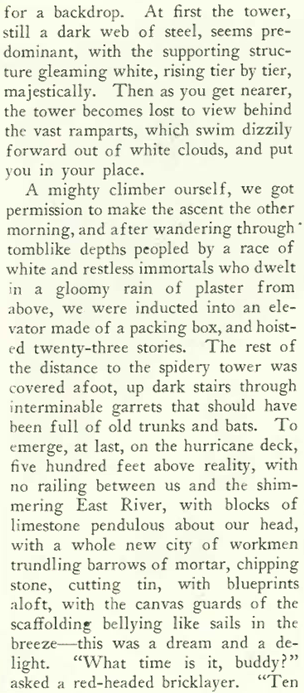

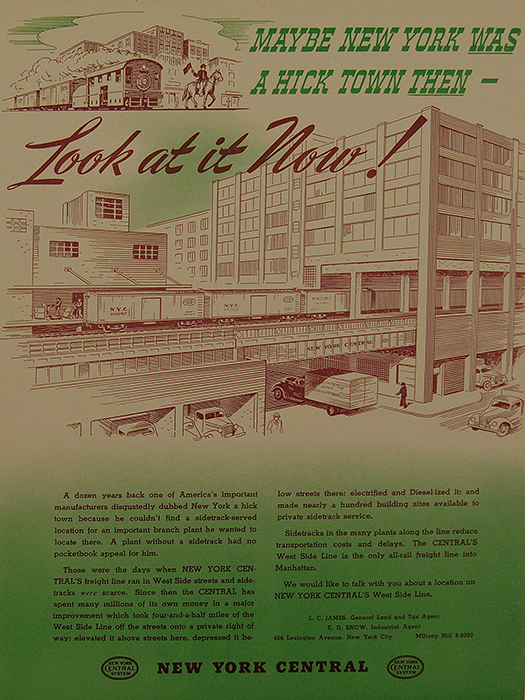

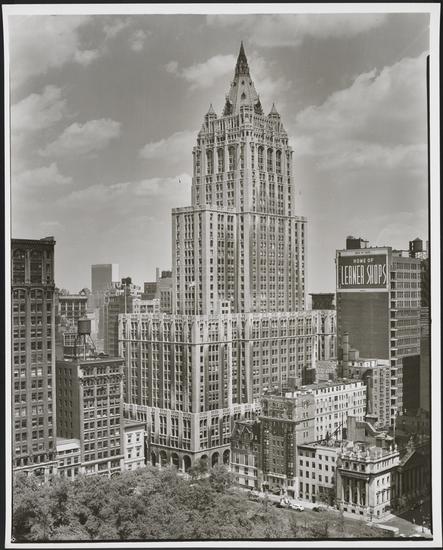

The March 17, 1928 “Talk of the Town” marveled at the rising structure between Madison and Park avenues that would become the New York Life Building. Designed by Cass Gilbert, who also designed the Woolworth Building, its gilded roof, consisting of 25,000 gold-leaf tiles, remains an iconic Manhattan landmark.

From 1837–1889, the site was occupied by the Union Depot, a concert garden, and P.T Barnum’s Hippodrome. Until 1925, the site housed the first two Madison Square Gardens, a memory that lingered amidst the city’s rapidly changing skyline…

* * *

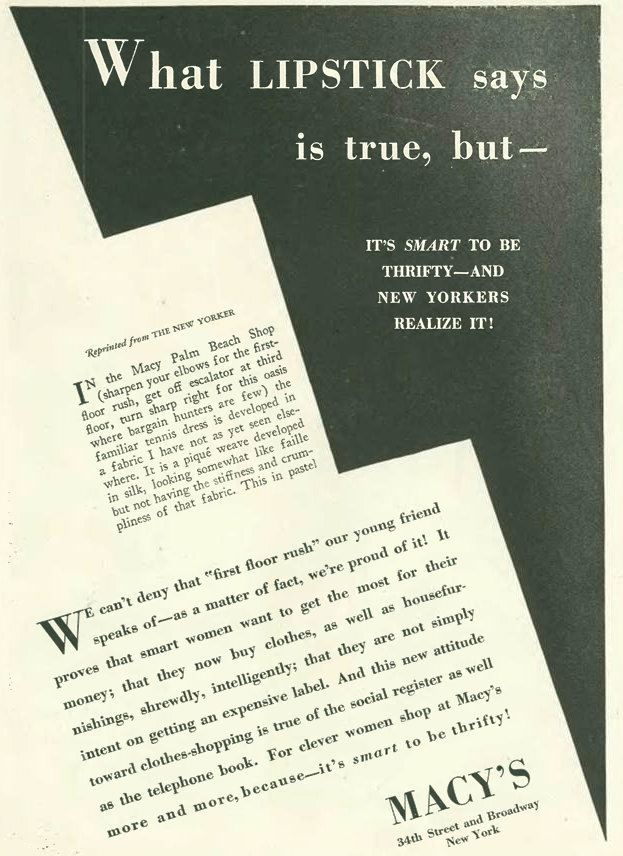

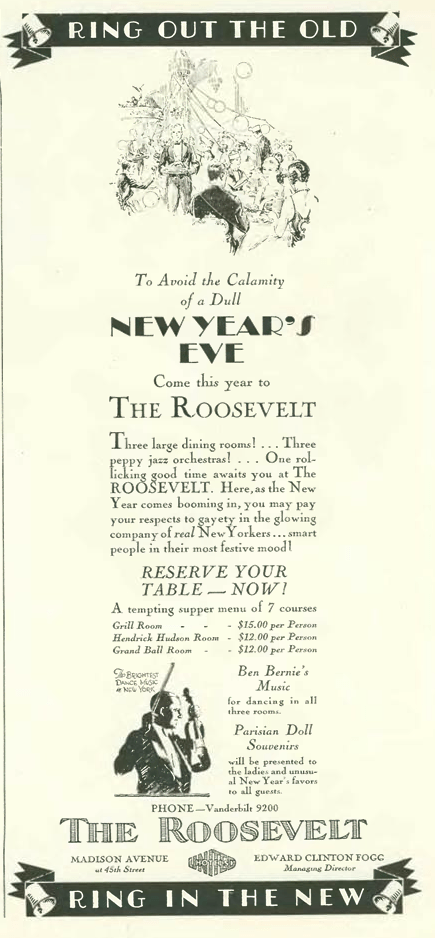

Following the lead of a Roosevelt Hotel advertisement in a previous issue, Macy’s Department Store also called out The New Yorker’s popular nightlife columnist “Lipstick” (Lois Long) in this ad featured in the March 17 issue…

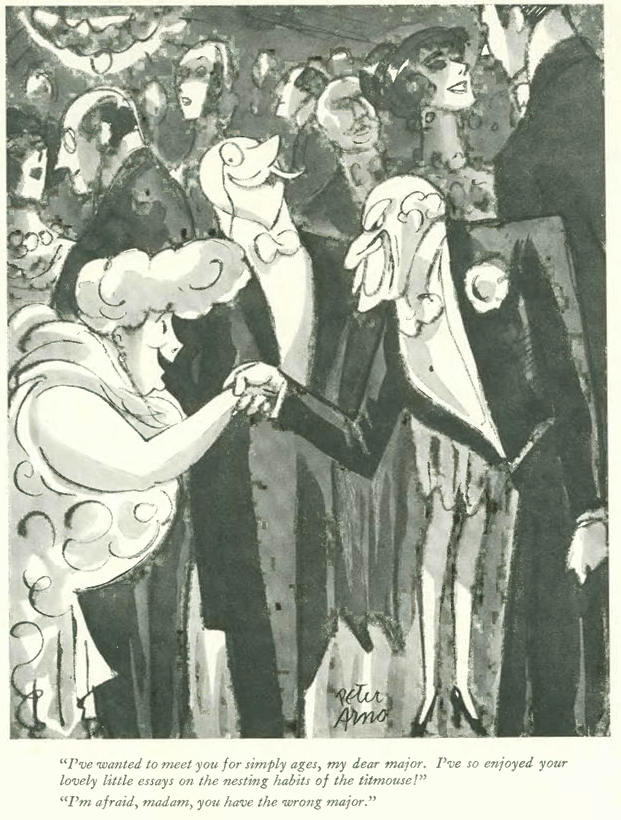

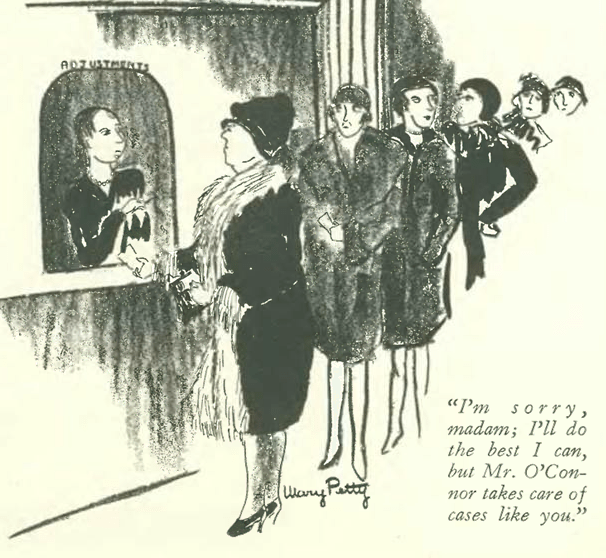

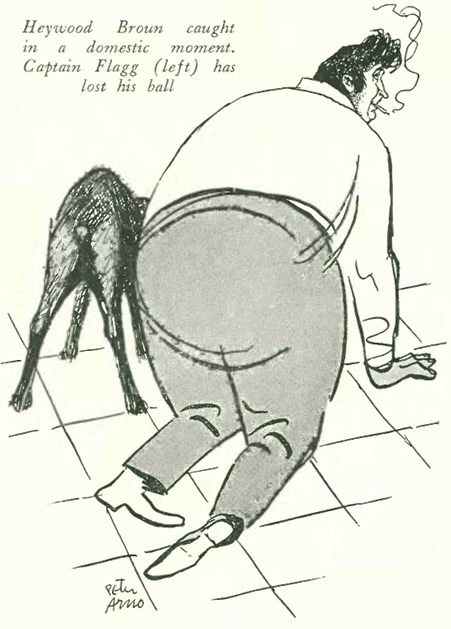

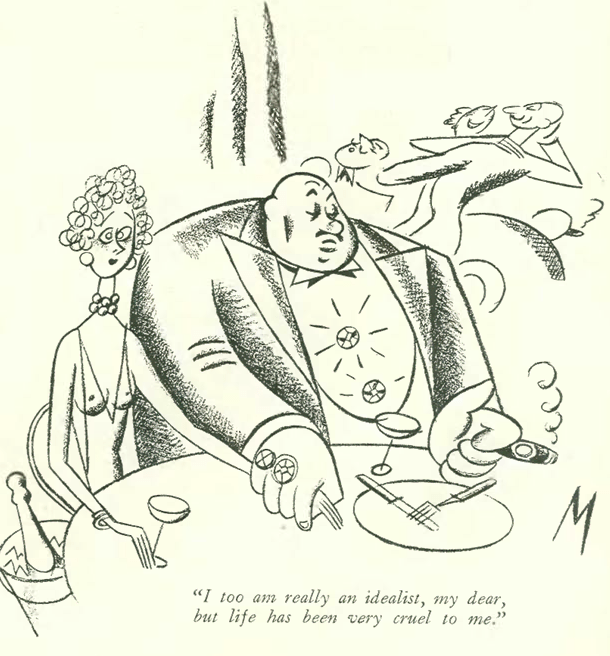

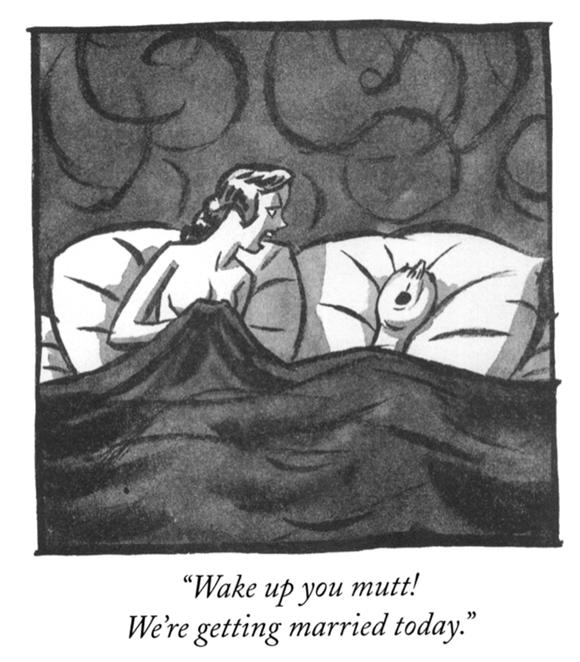

Our cartoon from the March 17 issue explored the hurried life of the idle rich, as depicted by Long’s husband, Peter Arno…

Landmark in Name Only

In the March 24, 1928 issue another building caught the attention of the magazine–a six-story structure designed by theatrical scenic artist and architect Joseph Urban for William Randolph Hearst. The International Magazine Building was completed in 1928 to house the twelve magazines Hearst owned at the time.

An important monument in the architectural heritage of New York, the building was designated as a Landmark Site by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1988. The six-story International Magazine Building was originally built to serve as the base for a proposed skyscraper, but the construction of the tower was postponed due to the Great Depression. The new tower addition by Norman Foster was finally completed nearly eighty years later, in 2006. It is probably not what either Hearst or Urban had in mind in 1928:

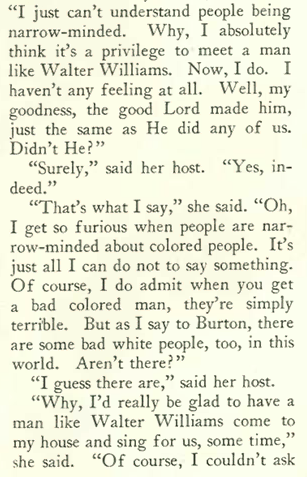

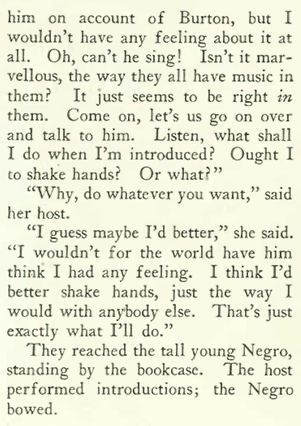

And finally, cartoonist Leonard Dove listens in on some tea time chatter…

Next Time: Conventional Follies of ’28…