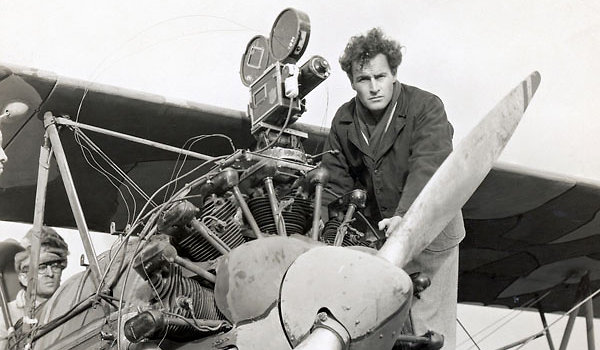

American inventor Thomas Edison was a hero to the young Henry Ford, who grew up to become something of a tinkerer himself with his pioneering development of the assembly line and mass production techniques. Over a matter of decades in the late 19th and early 20th century these two men would play outsized roles in transforming the American landscape and our way of life.

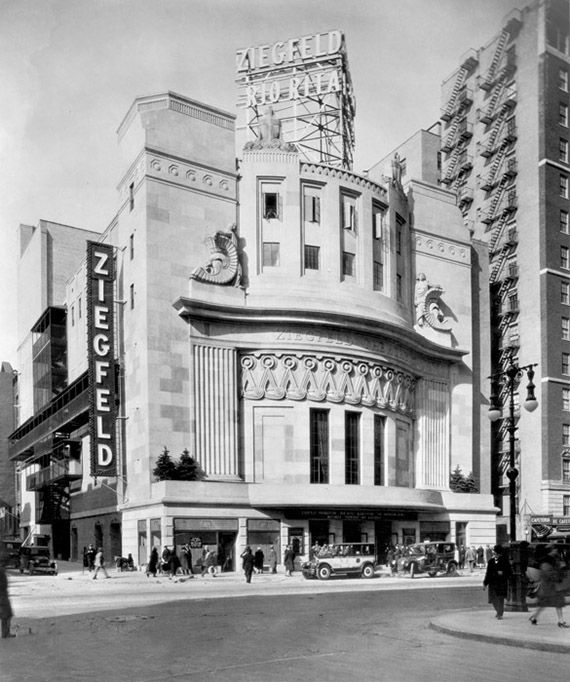

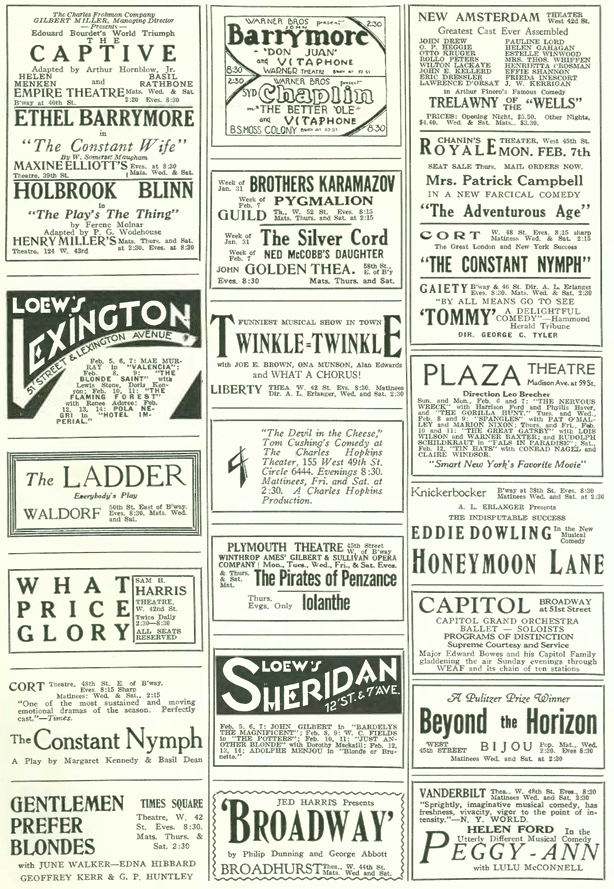

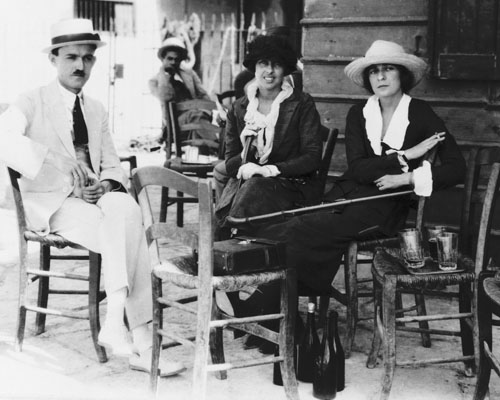

Ford would first meet Edison in August 1896, at a convention of the Association of Edison Illuminating Companies held at the Oriental Hotel in Brooklyn—it was just two months after the 33-year-old Ford had finished work on his first car—a “quadricycle”—consisting of a simple frame, an ethanol-powered engine and four bicycle wheels. In contrast, by 1896 the 49-year-old Edison was a worldwide celebrity, having already invented the phonograph (1877), the incandescent lamp (1879), public electricity (1883) and motion pictures (1888).

* * *

E.B. Drives the ‘A’

In the same issue (Jan. 21, 1928) E.B. White told readers how to drive the new Model A—in his roundabout way. Some excerpts:

No doubt White was feeling a bit wistful with the arrival of the Model A, which supplanted its predecessor, the ubiquitous Model T. White even penned a farewell to the old automobile under a pseudonym that conflated White’s name with Richard Lee Strout’s, whose original submission to The New Yorker inspired White’s book (illustrated by New Yorker cartoonist Daniel ‘Alain’ Brustlein).

In Farewell to Model T White recalled his days after graduating from college, when in 1922 he set off across America with his typewriter and his Model T. White wrote that “(his) own vision of the land—my own discovery of it—was shaped, more than by any other instrument, by a Model T Ford…a slow-motion roadster of miraculous design—strong, tremulous, and tireless, from sea to shining sea.”

The Eternal Debate

In his “Reporter at Large” column, Morris Markey commented on the execution of former lovers and convicted murderers Ruth Snyder and Judd Gray, noting that once again the debate over the death penalty had been stirred, but as usual there was no resolution in sight. Little could Markey know that we would still be holding the debate 89 years later, with no resolution in sight.

* * *

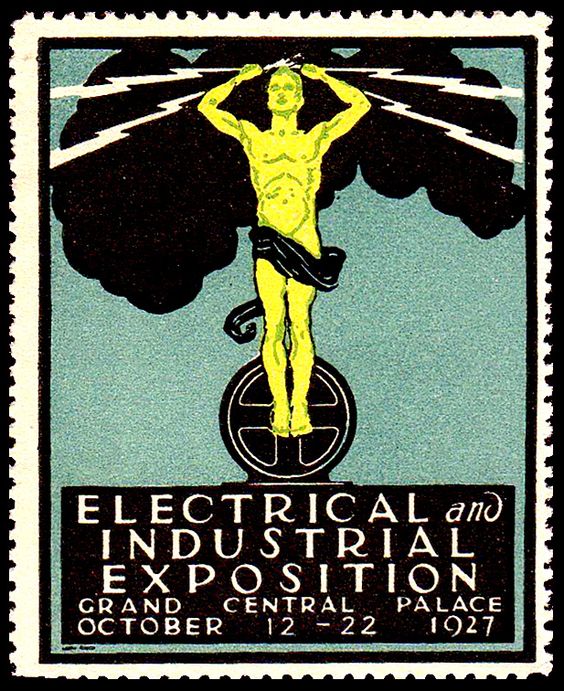

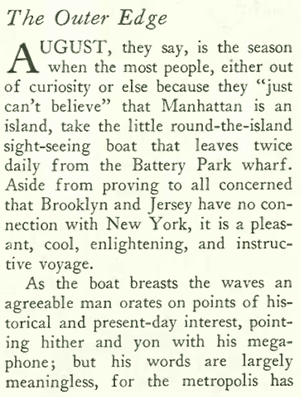

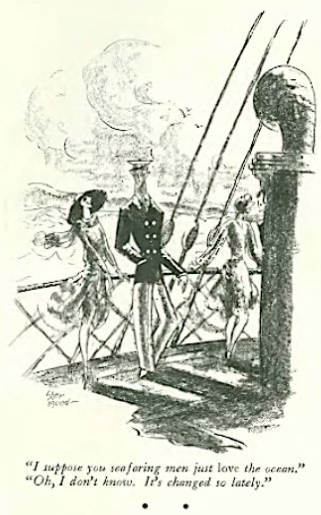

Ahoy there

The New York Boat Show was back in town at the Grand Central Palace, enticing both the rich and the not-so-rich to answer the call of the sea. Correspondent Nicholas Trott observed:

An advertisement in the same issue touted Elco’s “floating home”…

But if you aspired to something larger than a modest cruiser, the Boat Show also featured an 85-foot yacht…

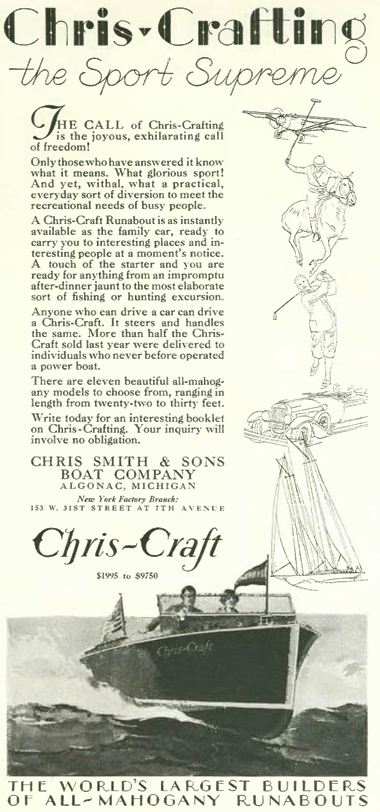

But for the rest of the grasping orders, Chris-Craft offered the Cadet, an affordable 22′ runabout sold on an installment plan. Another ad from the issue asking those of modest means to answer “the call of freedom!”

For an affordable boat, the Chris-Craft was really quite beautiful—its mahogany construction puts today’s fiberglass tubs to shame…

* * *

Odds & Ends

The boat show was one indication that spring was already in the air. The various ads for clothing in the Jan. 21 issue had also thrown off the woolens, such as this one from Dobbs on Fifth Avenue, which featured a woman with all the lines of a skyscraper.

And to achieve those lines, another advertisement advised young women to visit Marjorie Dork…

…who seemed to do quite well for herself in the early days of fitness training…

And then there was a back page ad that said to hell with healthy living…

The actress featured in the advertisement, Lenore Ulric, was considered one of the American theater’s top stars. Born in 1892 as Lenore Ulrich in New Ulm, Minnesota, she got her start on stage when she was still a teen, a protégé of the famed David Belasco. Though she primarily became a stage actress, she also made the occasional film appearance, portraying fiery, hot-blooded women of the femme fatale variety.

* * *

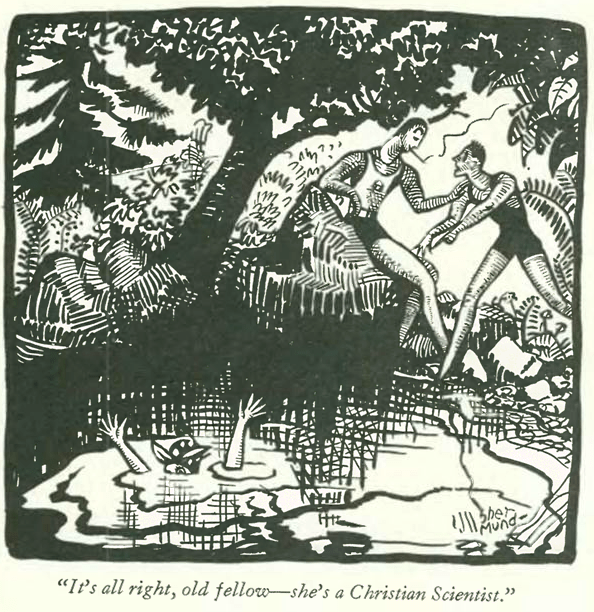

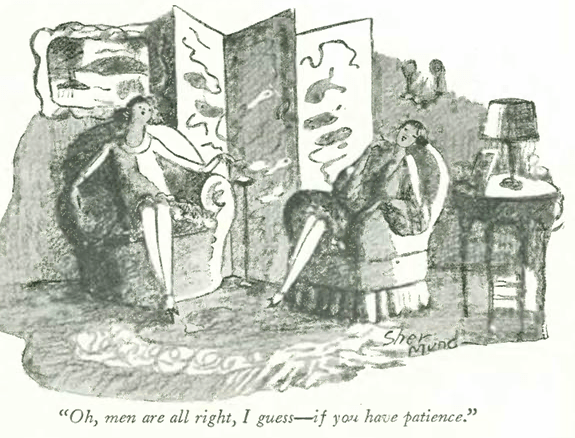

And we close with this post with a peek into the into upper class social scene, courtesy of Barbara Shermund…

Next Time: Distant Rumblings…