In the early years of The New Yorker, baseball as a sport was almost entirely ignored by the magazine, which otherwise gave exhaustive coverage to polo, yacht racing, tennis, and golf. There were also articles on badminton, rowing, and even auto racing, and college football received a lot of enthusiastic ink. But none for baseball. With the Sept. 22, 1928 issue I think I finally understand why.

It has something to do with The New Yorker’s parochial view of the world, so aptly illustrated by Saul Steinberg on the magazine’s March 29, 1976 cover, in which anything beyond the Hudson was essentially terra incognita:

A lot of New York Yankee fans came from “out there,” according to James Thurber in a “Talk of the Town” segment titled “Peanuts and Crackerjack.” Thurber wrote of his experience at a pennant race game between the Yankees and the Philadelphia A’s. The game of baseball was described as something for the out-of-towners who were “a bit mad,” a mass spectacle in which the game itself was of minor importance. In short, it wasn’t cool to be a Yankees fan if you counted yourself among Manhattan’s smart set:

This “Talk” item was written when the Yankees were on the verge of winning their second consecutive World Series championship over the favored St. Louis Cardinals. The 1928 team featured the famed “Murderer’s Row” lineup with the likes of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. In all, nine players from the ’28 team would be elected to the Hall of Fame, a major league record. But as of the Sept. 22 issue neither the 1927 or ’28 Yankees merited a line in The New Yorker’s sports pages.

Thurber wrote that one could learn much about those in attendance at the game by the way they received Yankee star Babe Ruth:

Thurber proved his point about out-of-towners by noting the origin of license plates in the “army of parked cars” outside of the stadium. He also noted the appearance in the game of an ancient Ty Cobb, who hit a weak fly ball while a few old-time fans looked on in reverence:

* * *

An Eye-dropping Art Collector

The Sept. 22 issue A.H. Shaw profiled “De Medici in Merion” Dr. Albert Barnes, who made his fortune by developing in 1901 (with German chemist Hermann Hille) a silver nitrate-based antiseptic marketed as Argyrol. In the days before antibiotics, Argyrol was used to treat eye infections and prevent newborn infant blindness caused by gonorrhea. The profile featured this rather fearsome illustration by Hugo Gellert:

The lengthy piece detailed Barnes’ coming of age, and how his promotion of Argyrol helped bankroll his famed art collection. A brief excerpt:

* * *

A One-eyed Monster Comes to Life

It’s always interesting to note the mentions of emerging technology in the early New Yorker, including this bit in Howard Brubaker’s column “Of All Things” about the successful broadcast of a “radio-television play.” Brubaker mused about what this new invention might called:

The first television broadcast in July 1928 was not exactly must-see TV. For two hours a day, General Electric’s experimental station W2XB broadcast the image of a 13-inch paper mache Felix the Cat, simply rotating on a turntable.

Then on September 11, 1928, W2XB (with WGY radio providing audio) broadcast a 40-minute one-act melodrama, The Queen’s Messenger. Northern State University’s Larry Wild writes that because TV screens were so small, only an actor’s face or hands could be shown. “The play had only two characters. A female Russian spy and a British Diplomatic Courier. Four actors were used. Two for the character’s faces, and two for their hands.”

* * *

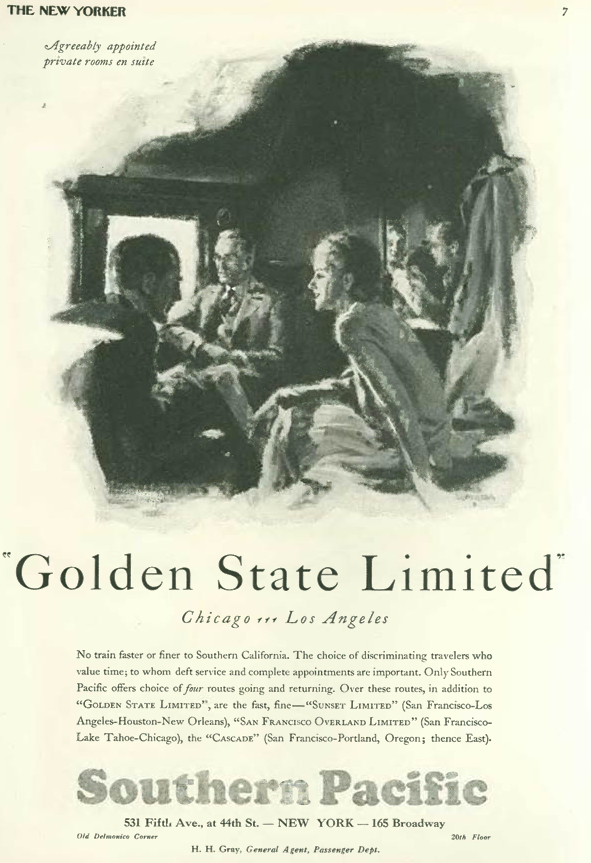

From Our Advertisers

Advertisers were always looking for clever angles to capture the attention of The New Yorker’s upscale readers, including the use of subtle and not-so-subtle racist cues to get their points across. Two examples from the Sept. 22 issue have the makers of Oshkosh trunks helpfully pointing out that their product is not intended for African “natives”…

…or the folks from Longchamps restaurants, who depict the joyless life of a blubber-eating Eskimo as an appropriate juxtaposition to the succulent delicacies awaiting readers at their five New York locations:

We might associate rumble seats with the carefree joys of the Roaring Twenties, but in reality passengers in these jump seats received little protection from the elements (or flying gravel), and the ride was no doubt jarring atop the rear axle. No wonder you needed a special coat:

Our cartoons for Sept. 22 include this whimsy from Gardner Rea…

…and this cartoon by Al Frueh, which depicts the deserted surroundings of the Flatiron Building on Yom Kippur. Robert Mankoff, who served as The New Yorker’s cartoon editor from 1997 to 2017, observed in the Cartoon Desk (Sept. 26, 2012) that “the rapid growth of Jewish-owned businesses in New York made the cartoon relevant in a way that it’s not today. Through modern, politically correct eyes, the cartoon may seem anti-Semitic, but I don’t see it that way. It just depicts the reality of those times, exaggerated for comic effect.”

Next Time: The Tastemakers…