Although there are some good indie and foreign films being made these days, not to mention some decent stuff on cable and streaming services, we still have plenty of bland popcorn fare coming out of Hollywood that combines the worst of unscrupulous producers and their fawning writers and directors.

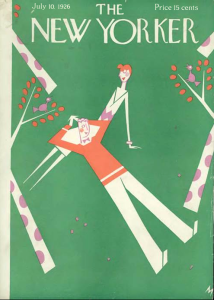

That’s how The New Yorker viewed Hollywood 90 years ago. Movie critic Theodore Shane weekly voiced his disappointment over American cinematic fare (while generally praising the work of European, and particularly German directors), and writer Morris Markey took the industry to task in the July 10, 1926 edition of the magazine, finding the whole lot of Hollywood to be a cesspool of mediocrity and dishonesty. It also didn’t help that Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers, was trying to enforce his morality code on the motion picture industry:

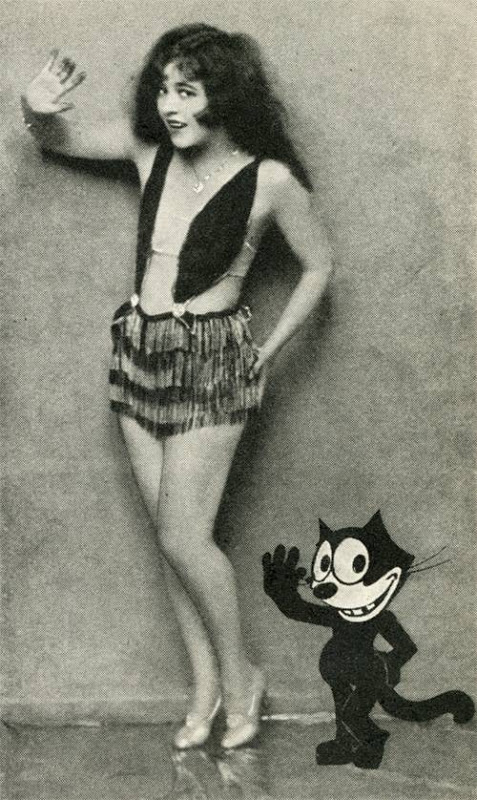

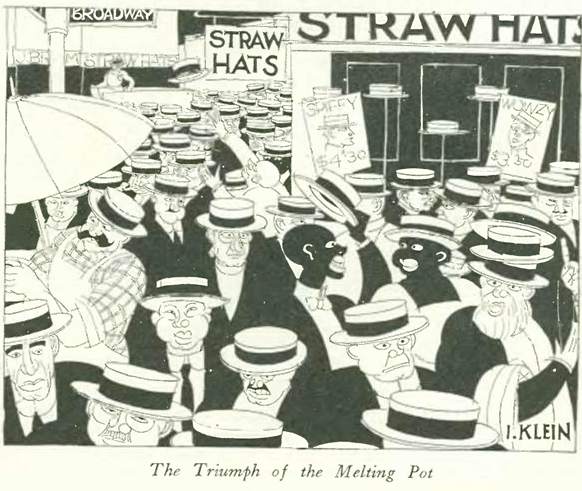

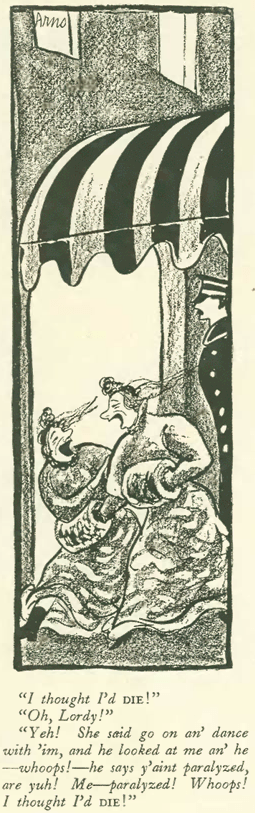

Here’s the full illustration by Isadore Klein that was cut off above, because it’s worth a look:

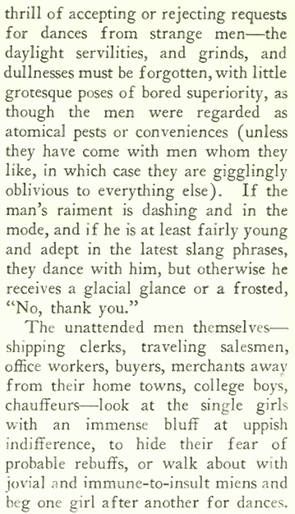

Later in the article Markey laid into the men in charge of the studios:

Markey also leveled scorn at the media, and gullible audiences, for supporting this tawdry spectacle:

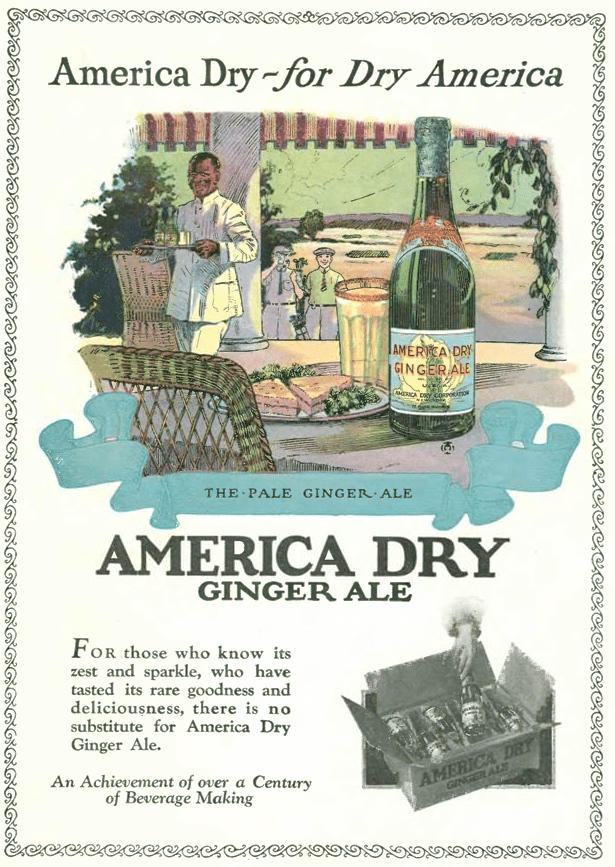

Motion Picture magazine and others of this ilk were the US magazines of the 1920s:

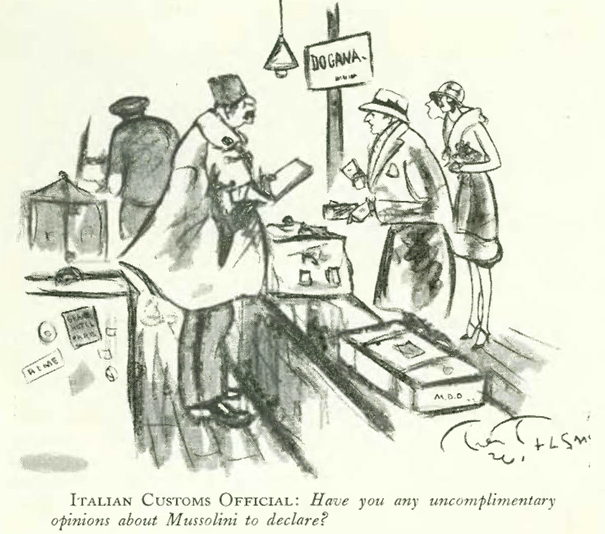

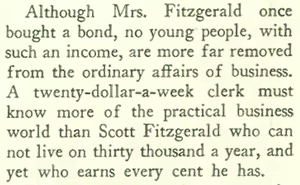

And finally, a couple of bits for my “They Didn’t Know What Was Coming” department. Generally people were having too good of a time in the Roaring Twenties to take this fascism thing very seriously. From the section “Of All Things:”

And from “The Talk of the Town” section, a cartoon by W.P. Trent:

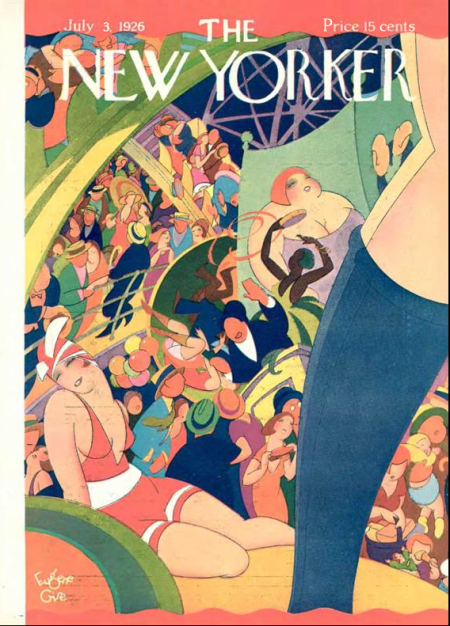

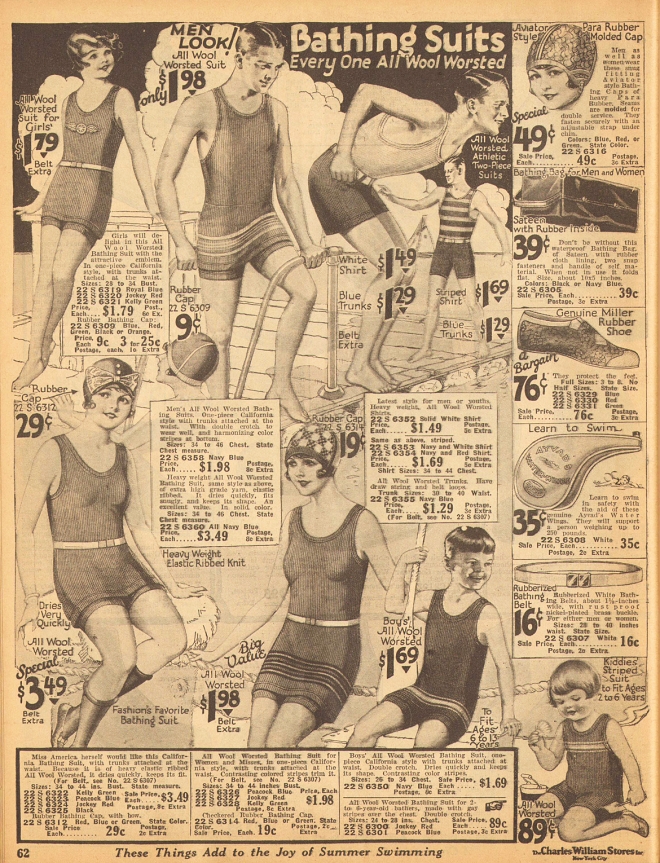

Next Time: The Good Old Summertime…