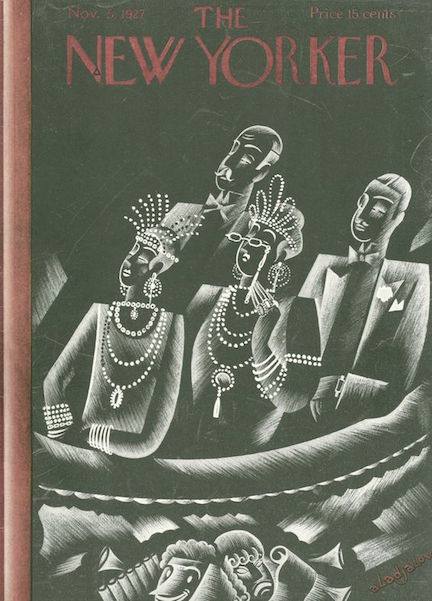

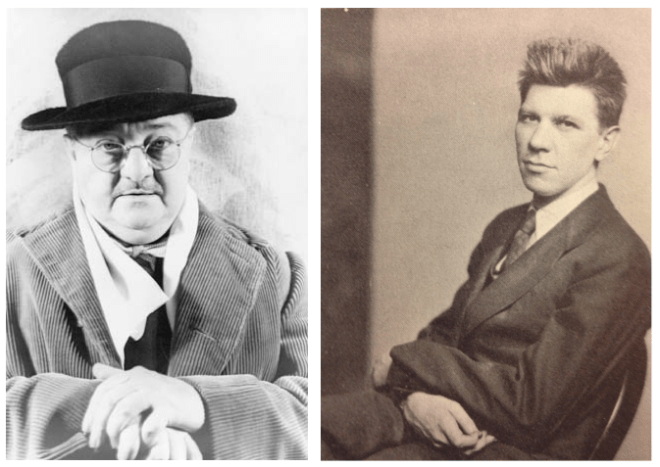

Like his good friend Charlie Chaplin, Ralph Barton wore a mask of a clown that hid a face of bitter anguish. Chaplin would cope, more or less. Barton would not.

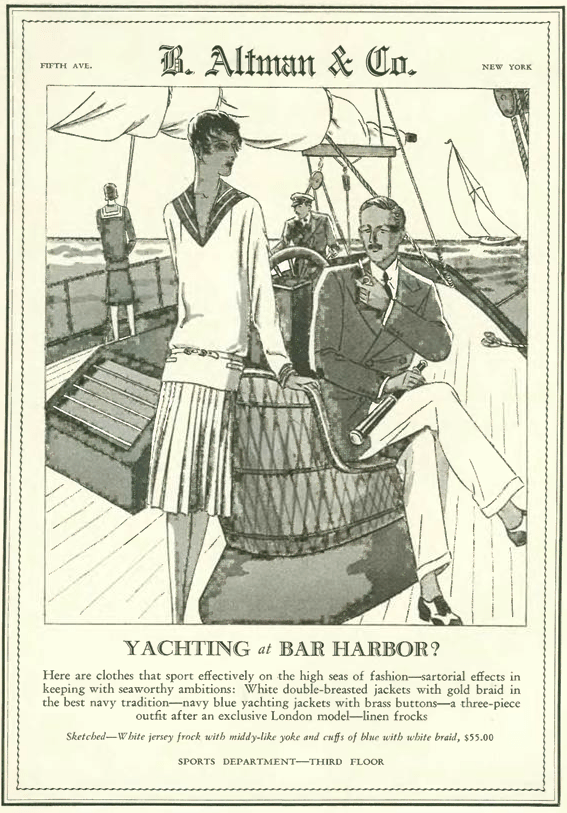

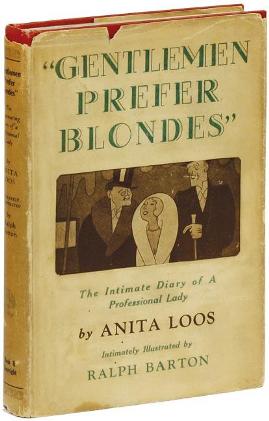

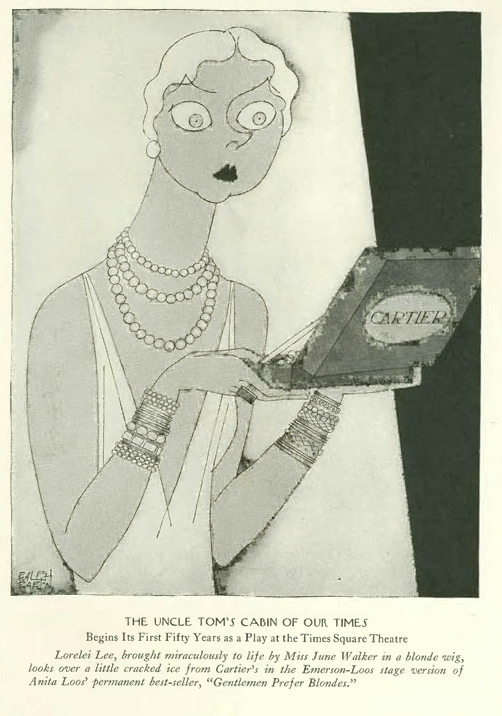

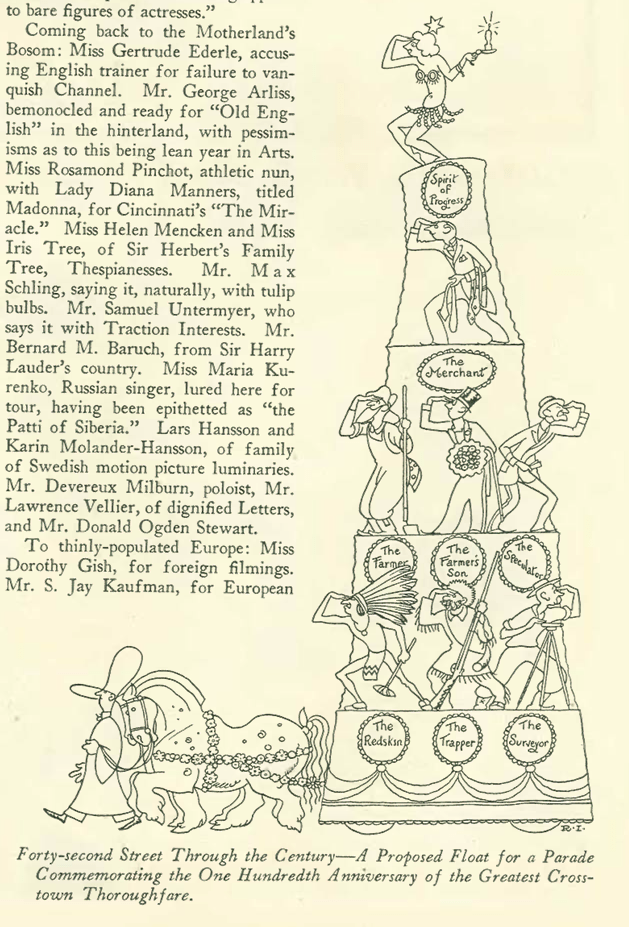

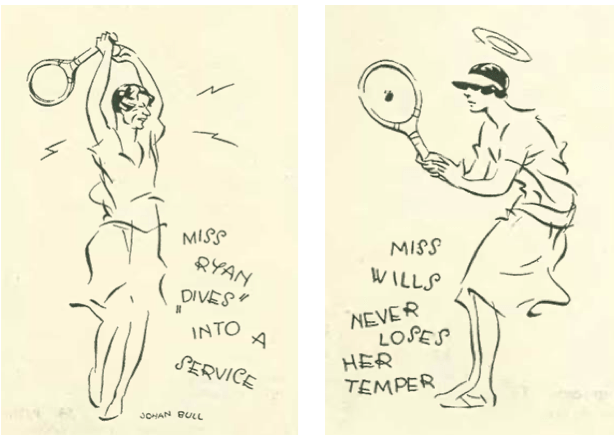

A member of the New Yorker gang from the very beginning, Barton served as the magazine’s advisory editor but more famously as a caricaturist of the Roaring Twenties, also contributing to the likes of Harper’s Bazaar, Collier’s, Vanity Fair and Judge. He also illustrated one of the most popular books of the Twenties, Anita Loos’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes:

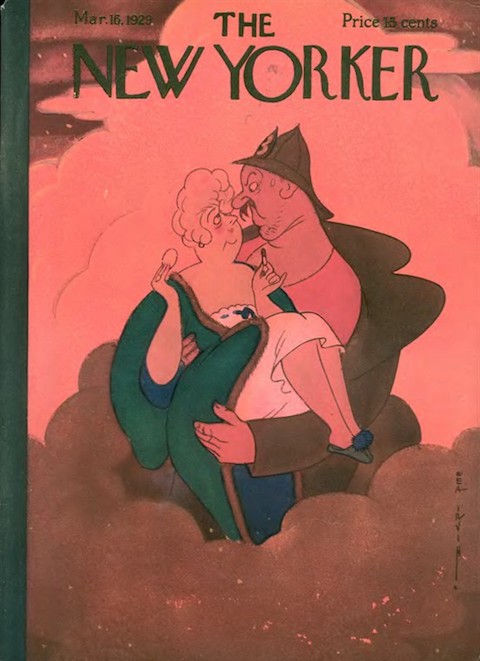

In 1929 Barton would publish a book of his own, God’s Country, which was reviewed in the March 16, 1929 edition of the New Yorker:

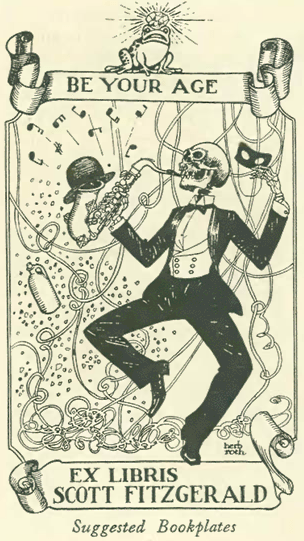

The same issue featured this advertisement from Knopf promoting God’s Country as the latest addition to its lovely Borzoi Books collection (and endorsed by composer and Barton friend George Gershwin)…

Some excerpts from the book…(click to enlarge)

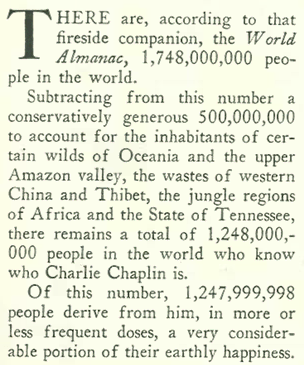

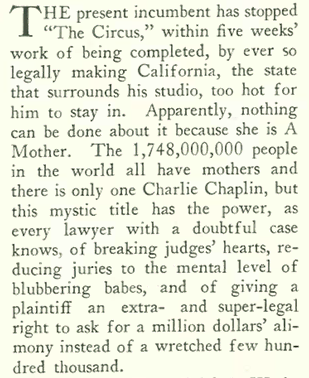

Barton was a longtime friend of Charlie Chaplin, even coming to the silent film star’s defense (in the pages of the July 23, 1927 New Yorker) when many Americans turned their backs on the comedian during a messy and much publicized divorce trial. In that New Yorker piece Barton concluded that France would be a better, more welcoming home to such an artist:

The manic-depressive Barton had his own problems in the love department, marrying four times in his short life, most famously to wife No. 3, stage and film actress Carlotta Monterey, who divorced Barton in 1926 and married playwright Eugene O’Neill in 1929. Although Barton would marry again, he would never recover from his loss of Monterey.

A little more than two years after publishing God’s Country—May 19, 1931—the 39-year-old Barton shot himself through the right temple in his East Midtown apartment. He referred to Carlotta Monterey in his suicide note, writing that he had lost the only woman he’d ever loved. He also wrote: “I have had few difficulties, many friends, great successes; I have gone from wife to wife and house to house, visited great countries of the world—but I am fed up with inventing devices to fill up twenty-four hours of the day.”

As the exuberance of the Jazz Age faded into the Depression, so did Barton’s reputation as a chronicler of that age. An abstract for the 1998 Library of Congress exhibition Caricature and Cartoon in Twentieth-Century America notes that “in a good week he (Barton) could make $1,500 (about $22,000 today) but a couple of years after his early death his caricature of George Gershwin sold for $5.”

The last caricature Barton ever drew was of his old friend, Charlie Chaplin.

Note: I took the title of this blog entry from a 1991 book on the life of Ralph Barton: The Last Dandy, Ralph Barton, American Artist, 1891-1931, by Bruce Keller.

Babbitt Babble

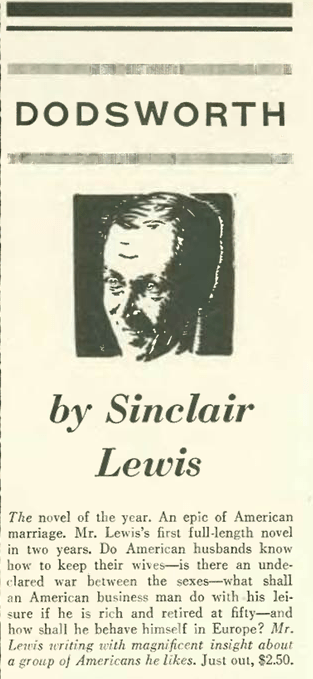

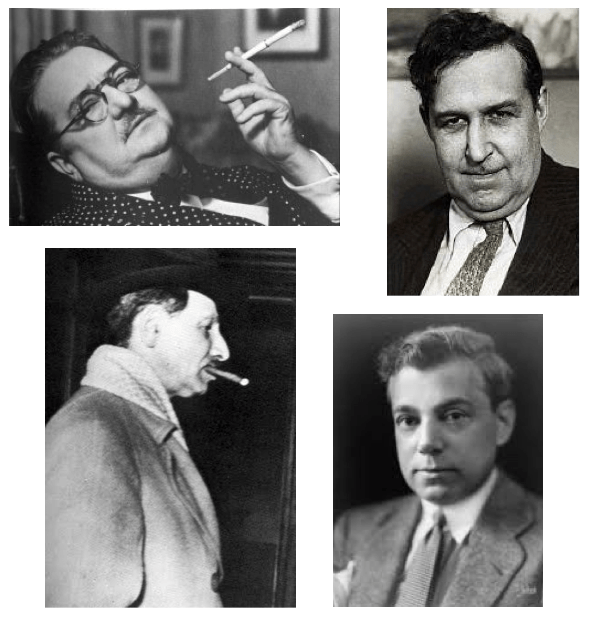

Preceding the review of Barton’s book in the March 16 New Yorker was this much less complimentary review of Sinclair Lewis’s latest effort, Dodsworth, a story in the tradition of Henry James about wealthy middle-class Americans on a grand tour of Europe.

The task of skewering Lewis and his book fell to Dorothy Parker, who would never mistake Lewis for Henry James: ““I can not, with the slightest sureness, tell you if it (Dodsworth) will sweep the country, like ‘Main Street,’ or bring forth yards of printed praise…My guess would be that it will not. Other guesses which I have made in the past half-year have been that Al Smith would carry New York state, that St. John Ervine would be a great dramatic critic for an American newspaper, and that I would have more than twenty-six dollars in the bank on March 1st. So you see my my confidence in my judgment is scarcely what it used to be.”

Parker took particular umbrage at Lewis’s use of the name of a character from another book as a descriptive term for his latest:

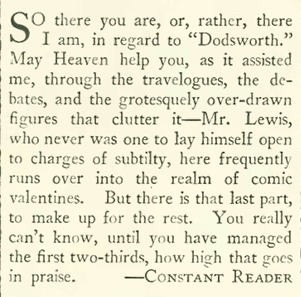

Parker concluded that if a reader could wade through the book’s cluttered language and “grotesquely over-drawn figures,” there was a conclusion that was perhaps worth pursuing…

…the New Yorker was never afraid to bite the hand that fed it (except Raoul Fleischmann’s, whose money saved the magazine from an early death), so even though its author was savaged on the opposite page, Dodsworth’s publisher Harcourt still sprung for an ad:

* * *

This Geometric Life

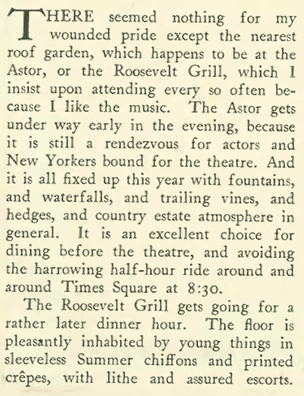

The author of the March 16, 1929 “Comment” (Leading item of “The Talk of the Town”) found the “geometric life” dictated by modern design took some getting used to. This entry was most likely written by E.B. White:

* * *

Mexican Firecracker

Mexican actress and emerging star Lupe Velez caught the eye, and ear, of the New Yorker in her latest film, Lady of the Pavements…

An ad in the same issue of the New Yorker touted the film’s appearance at Public Theaters, a chain owned by Paramount:

Well-known for her explosive screen presence, Velez was big star in the 1930s. Married to Tarzan actor Johnny Weissmuller from 1933 to 1939, her star began to fade at the end of the decade. She died of a drug overdose in 1944, just 36 years of age.

* * *

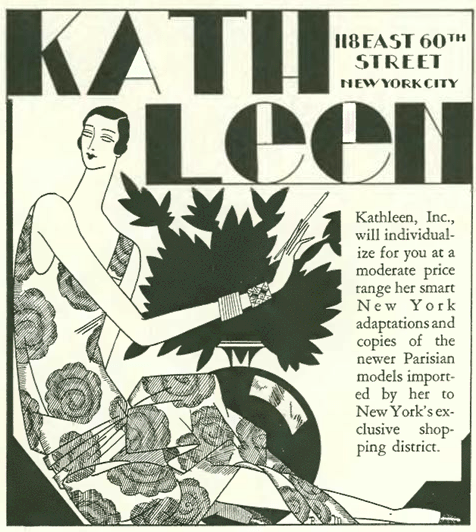

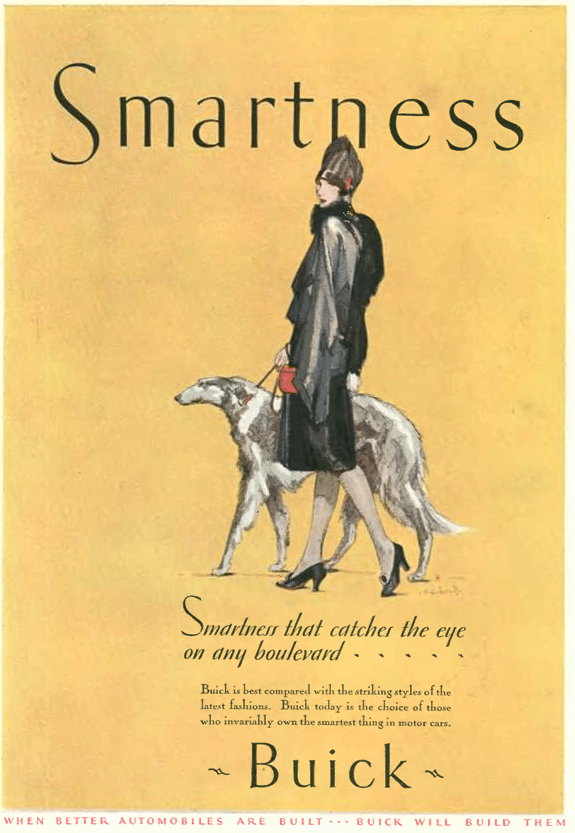

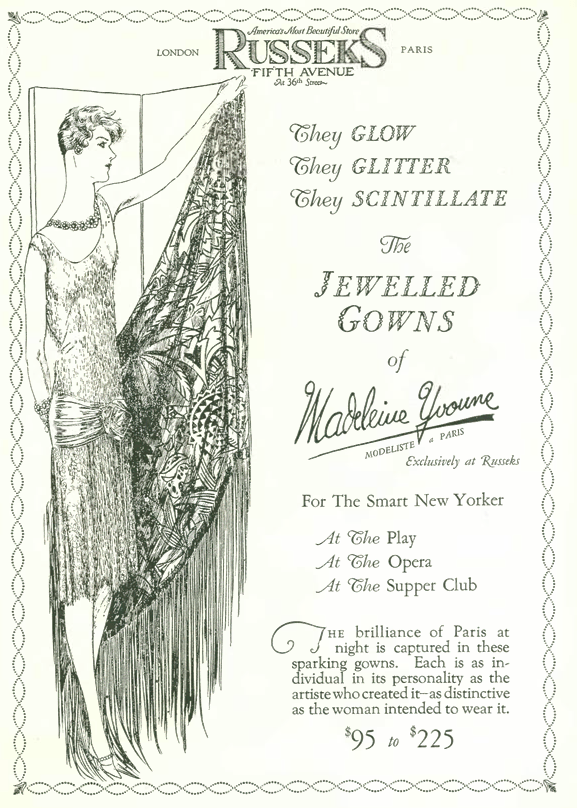

From Our Advertisers

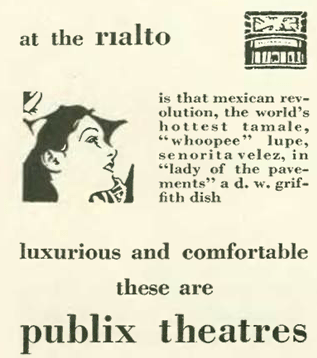

A few advertisements that caught my eye from the March 16 issue…one thing you notice is the emerging sophistication of advertising techniques, including this ad for Resilio Cravats that enticed by deliberating not showing the product…

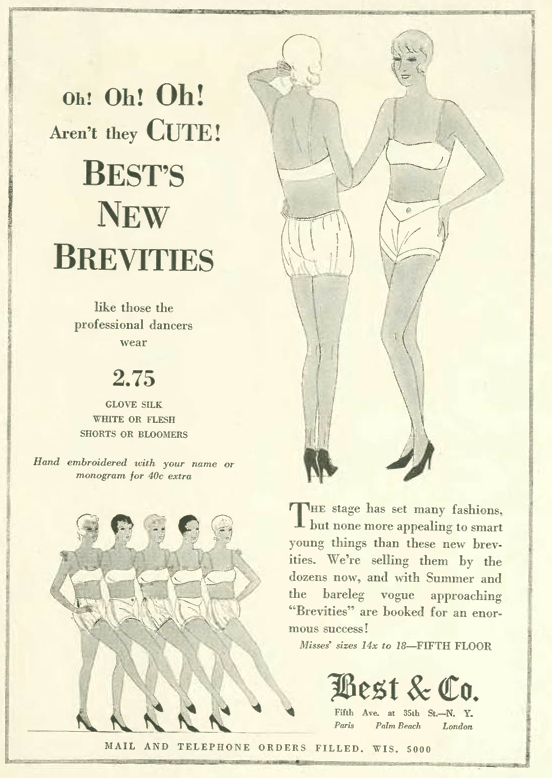

…and this ad that demonstrated Best & Co. was not shy at all to show women in their skivvies (or suggest that they could wear the same undergarments as a Follies performer)…

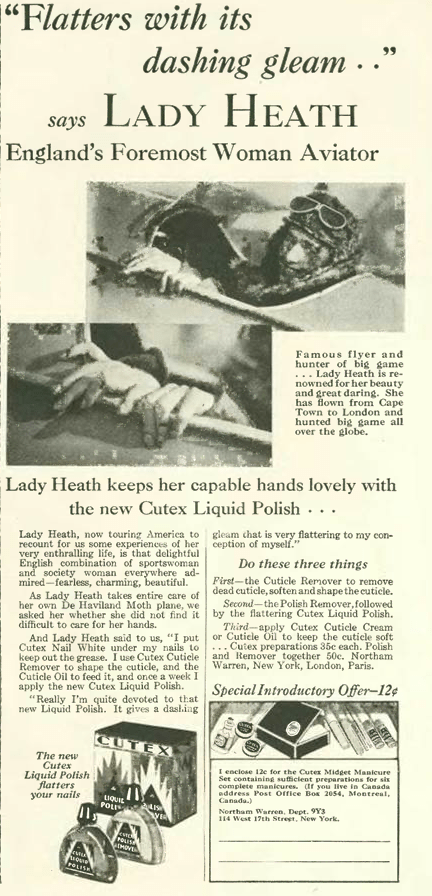

…and then we have this strange ad for Cutex nail polish, with an endorsement by Sophie Peirce-Evans, later known as Mary, Lady Heath, a well-know aviatrix (dubbed “Lady Icarus”) of the 1920s who shared headlines with Amelia Earhart for her high-flying derring-do. The close-up shot of the hands is priceless…

…and then we have another celebrity endorsement of a cigarette by a society figure—interior designer and social maven Elsie de Wolfe, who was also known as Lady Mendl…

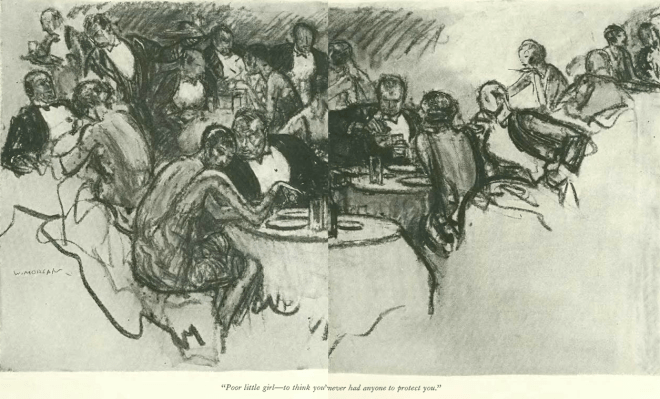

…and on to the cartoons…Peter Arno listened in on two young debutantes sizing up a dowager at a society gathering…

…while Garrett Price looked in on well-heeled visitors to the Metropolitan Museum of Art contemplating what appears to be the work of W.A. Dwiggins in the museum’s The Architect & the Industrial Arts exhibition…

Next Time: Queen of the Night Clubs…