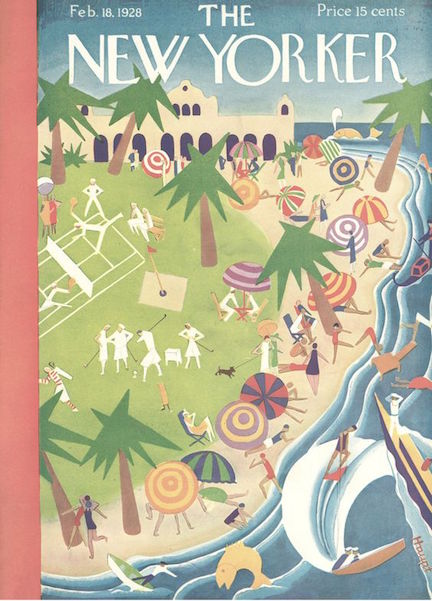

In 1928 Al Capone bought an estate on Miami’s Palm Island as a getaway from the hustle and bustle of Chicago gangster life. He was apparently basking in the Florida sun on Feb. 14, 1929 when four of his associates gunned down seven members of a rival Irish gang on Chicago’s North Side.

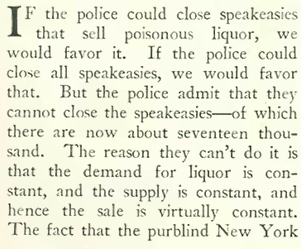

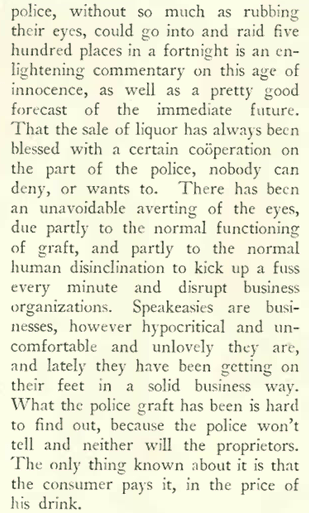

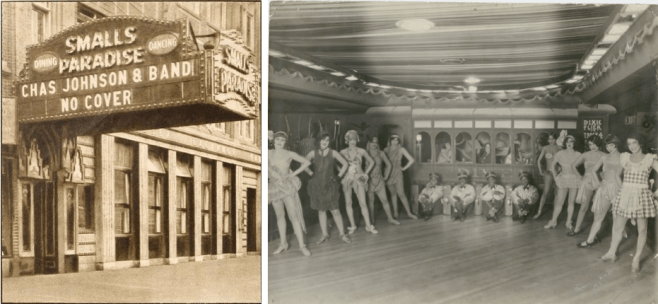

It is widely believed Capone ordered the killings, given that he dominated Chicago’s illegal bootlegging, gambling and prostitution trades and was known for his ruthless elimination of rivals. On the heels of the St. Valentine’s Day massacre, James Thurber contributed this item in the New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” describing a more mundane side of gangster life:

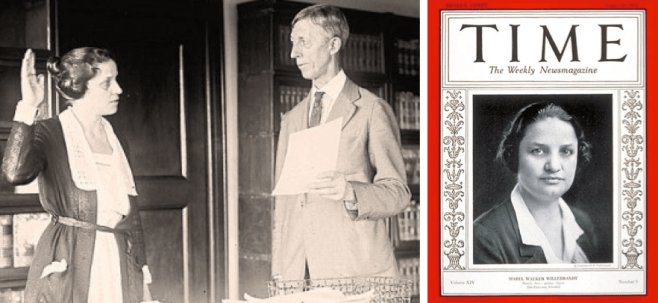

Shortly after Thurber’s article appeared in the March 2, 1929 New Yorker, Capone would be arrested in Chicago by FBI agents on a contempt of court charge and again in May 1929 on a weapons charge. The following March Capone would be referred to as “public enemy number one” by the Chicago Crime Commission, and a month later he would be arrested on vagrancy charges during a visit to Miami—the Florida governor wanted him out of the state. In 1932 Capone would be sent to Federal Prison for tax evasion.

When Capone finally returned to Palm Island in 1940, he was a very different man. When he entered the U.S. Penitentiary in Atlanta in 1932 he was found to be suffering from both syphilis and gonorrhea, and when he was released seven years later his mental capacities were severely diminished due to late-stage syphilis. In 1946 a physician concluded Capone had the mentality of a 12-year-old child. He died on Jan. 25, 1947, having just turned 48 years old.

Another mention of the St. Valentine’s Day massacre could be found in Howard Brubaker’s column “Of All Things”…

* * *

Pierre’s Hotel

Back in New York, patrons of famed chef Charles Pierre Casalasco were abuzz over his plans for a luxury high-rise hotel. Writing in “Talk of the Town,” Leonard Ware made these observations about Pierre’s big plans:

Ware recounts how Pierre went from humble busboy to renowned haute cuisine restaurateur:

* * *

Famed Bluestocking

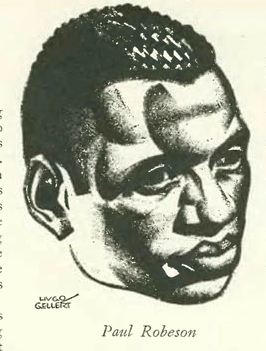

The New Yorker’s Paris correspondent, Janet Flanner, who wrote under the pen name Genêt, wrote under her own byline for the first time in a profile of the famed novelist Edith Wharton, featured in the March 2 issue. Although born a New Yorker, Wharton mostly lived in France after 1914. Below is a drawing of Wharton by Hugo Gellert that accompanied the profile, of which a few excerpts are included below:

* * *

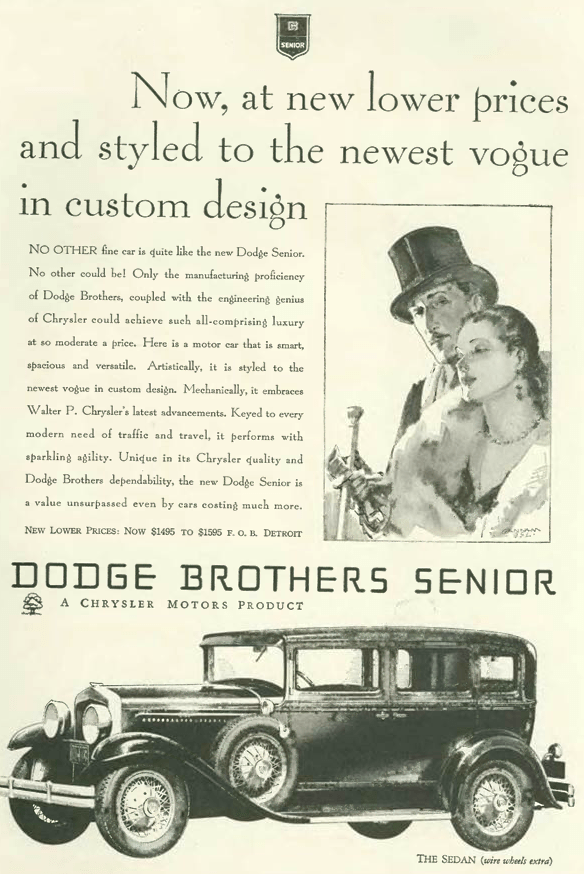

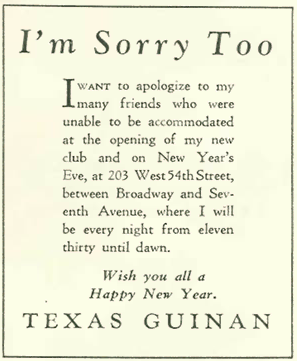

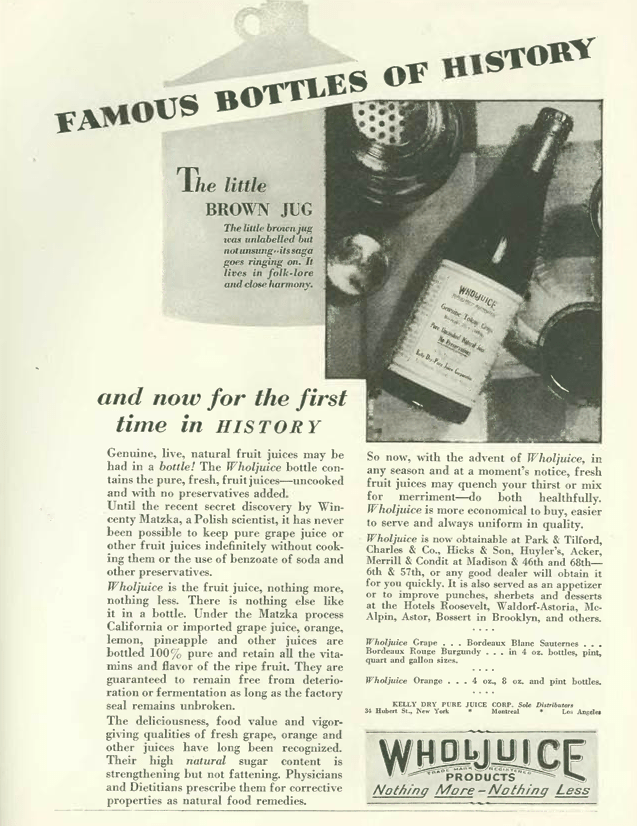

From Our Advertisers

Automobile manufacturers were keen to snob appeal even 90 years ago, as can be seen in this advertisement for Dodge cars—the company had been acquired the previous year by Walter Chrysler. Dodge cars were noted for dependability and value, but this ad suggested even blue bloods would find them appealing…

…Chrysler did however take a more direct aim at the top-hat set with a new model— Imperial—to compete with luxury carmakers such as Lincoln and Cadillac…

…just for kicks, this is what the Chrysler Imperial would look like just 30 years later…

…not to be left out, Cadillac placed its downscale luxury model next to Mont-Saint-Michel in this illustrated advertisement. The LaSalle was comparable in price to the Imperial (around $2,500 to $3000) while top-of-the-line Caddies were priced up to $7000…

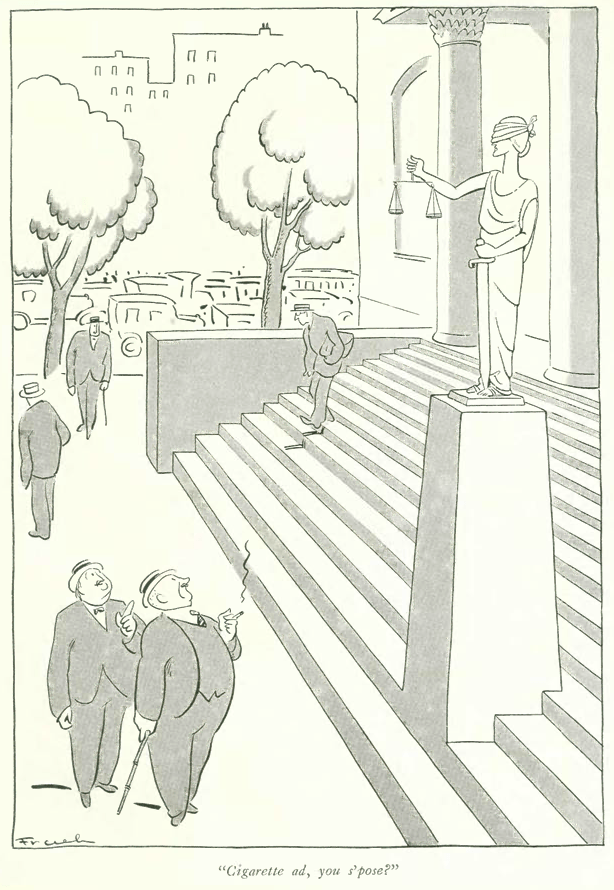

…and what do you put in your fine automobile to make it purr? Why gasoline mixed with tetraethyl lead, of course!

Speaking of mixing, I like this advertisement for Cliquot Club, whose manufacturers finally—and not so subtly—hint at how their product is to be enjoyed…

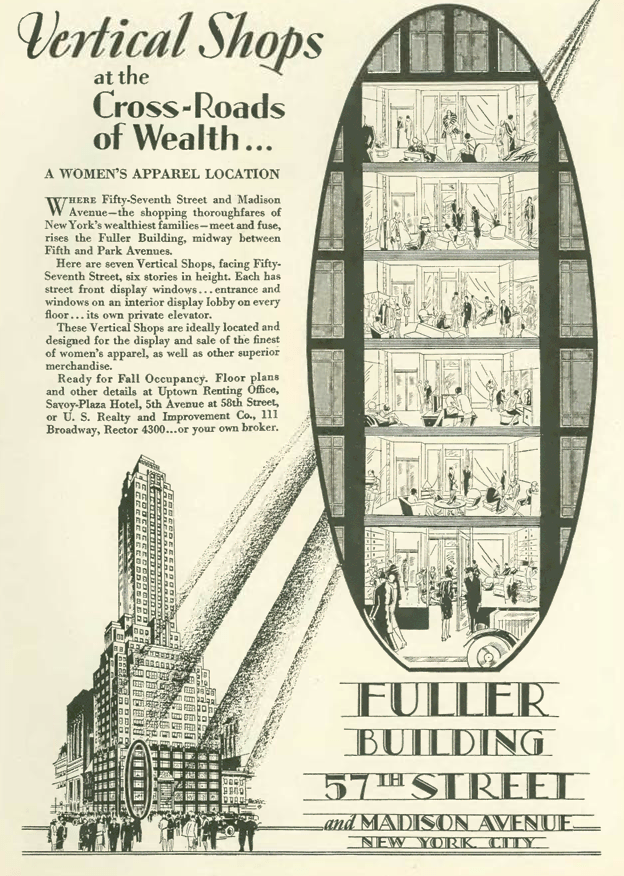

…and finally, this ad for the new Fuller Building, which touted gallery spaces for “superior merchandise” on its first six floors…

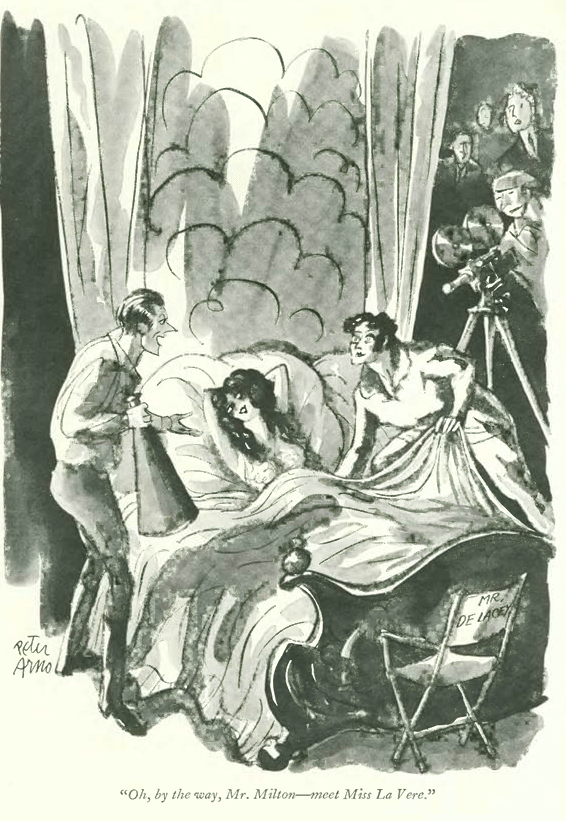

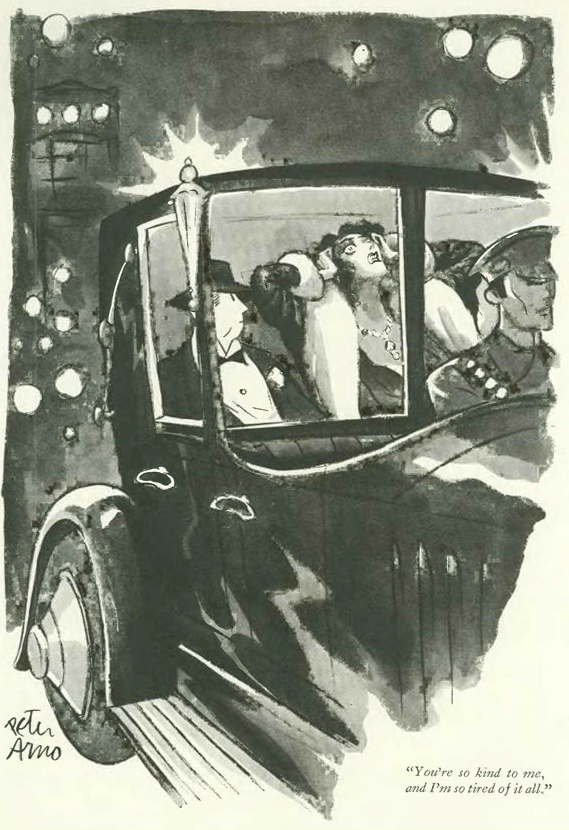

In the cartoon department, we have I. Klein’s take on recent activities associated with the inauguration of President Herbert Hoover…

…and Abe Birnbaum, who provided this sketch of Hoover for the opening pages…

…Otto Soglow’s manhole denizens looked for signs of spring…

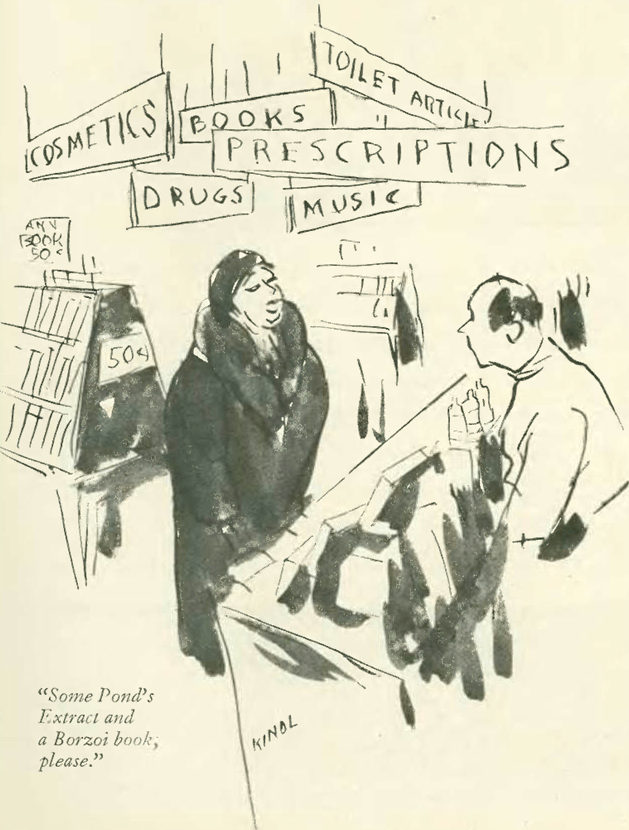

…and finally, a comment on the diversification of drugstore wares, by a cartoonist signed as “Kinol.” I’ve had no luck tracing this name, so if anyone has the scoop on this artist, please drop me a note!

Next Time…Sky-High Fitness…