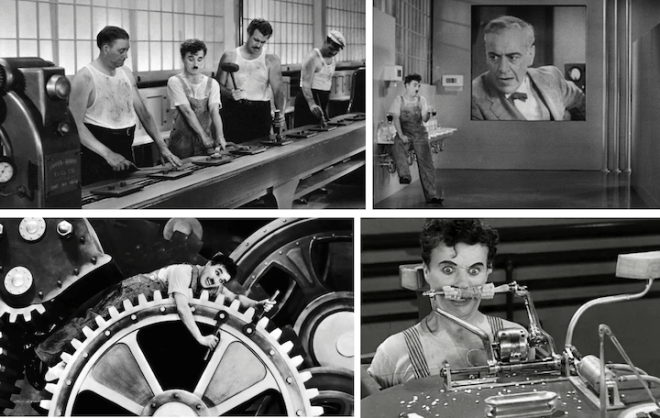

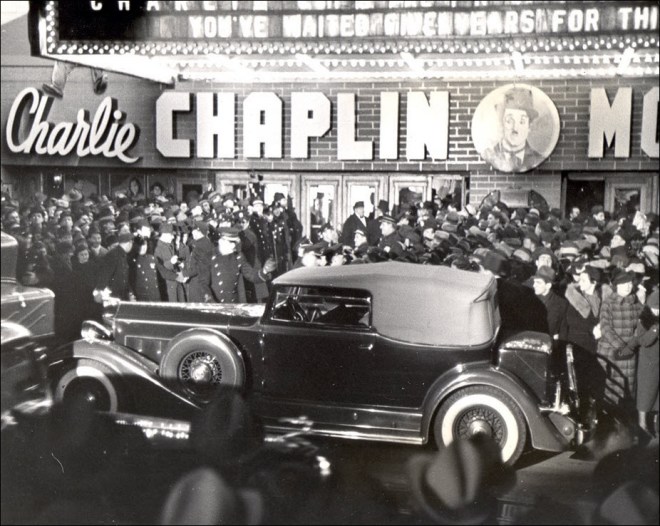

Above: A mechanic (Chester Conklin) gets caught up in his work with the help of the Tramp (Charlie Chaplin) in Modern Times. (festival-entrevues.com)

The film Modern Times was Charlie Chaplin’s last performance as “The Tramp” (or, “The Little Tramp”), a character he created more than twenty years earlier to represent a simple person’s struggle to survive in the modern world. That struggle was no more apparent than in Modern Times, a film in which the Tramp faced the dehumanizing industrial age in all its kooky complexity.

The film is notable for being Chaplin’s first picture to feature sound, and the first in which Chaplin’s voice is heard—singing Léo Daniderff’s comical song “Je cherche après Titine” (although Chaplin replaced the lyrics with gibberish). Modern Times was nevertheless filmed as a silent, with synchronized sound effects and a small amount of dialogue. Critic John Mosher appreciated the movie as being “of the old era,” not anticipating that it would become one of cinema’s most iconic and beloved films.

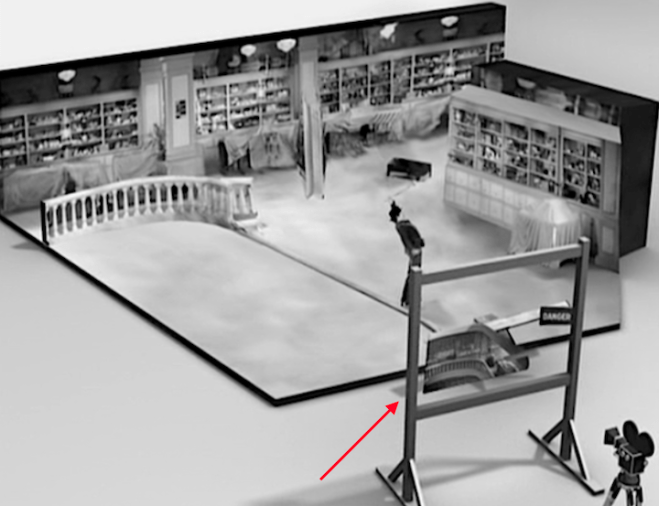

One of the film’s best stunts involved the blindfolded Tramp rollerskating on the fourth floor of an under-construction department store; Chaplin employed a matte painting, perfectly applied on a glass pane in front of a camera, to create the illusion of a sheer drop-off. Even as an illusion, Chaplin’s skating skills were remarkable.

The model below shows how the effect was achieved, filming next to a glass-mounted matte painting to create the illusion of a sheer drop off…

In his conclusion, Mosher found the film to be “secure in its rich, old-fashioned funniness.”

Chaplin gave a happy send-off to the Tramp, who at the end of earlier films walked down the road alone. Modern Times closed with the Tramp and the Gamin walking hand in hand, dreaming of a life together.

A final note: The website The Twin Geeks offers an excellent synopsis and analysis of Modern Times.

* * *

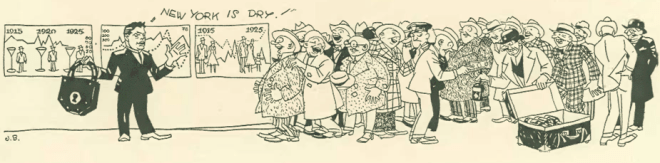

Bachelor King

In his “Notes and Comment,” E.B. White wrote about the ascension to the British throne by Edward VIII following the death of his father, George V. In this excerpt, White considered a question raised by the Daily News regarding the king’s plans to marry (a question answered a few months later when Edward announced his plan to wed American divorcee Wallis Simpson, which led to a constitutional crisis and Edward’s subsequent abdication).

* * *

By Any Other Name

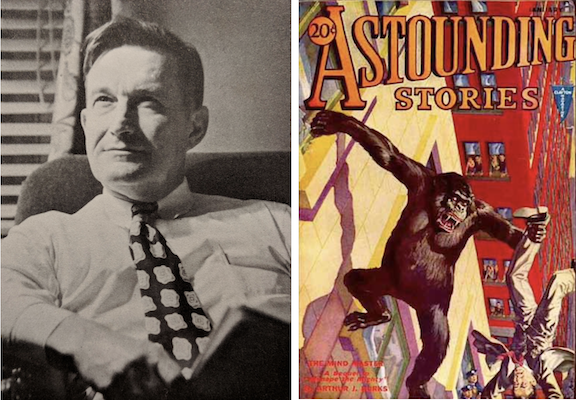

“The Talk of Town” featured a profile of Arthur J. Burks, a prolific writer of pulp fiction who published everything from detective stories to science fiction under a half-dozen pseudonyms. A brief excerpt:

* * *

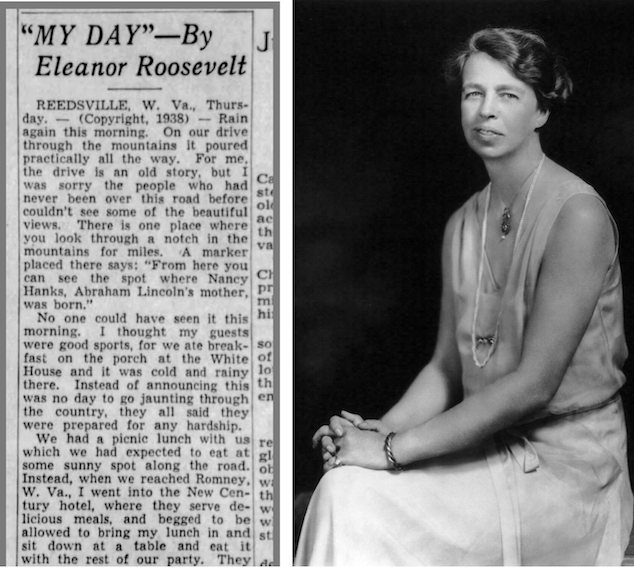

A Day in the Life

From 1935 to 1962 Eleanor Roosevelt published a daily syndicated newspaper column titled “My Day”—through the column millions of Americans learned her views on politics, society, and events of the day as well as details about her private and public life. James Thurber couldn’t resist writing a parody—here’s an excerpt:

* * *

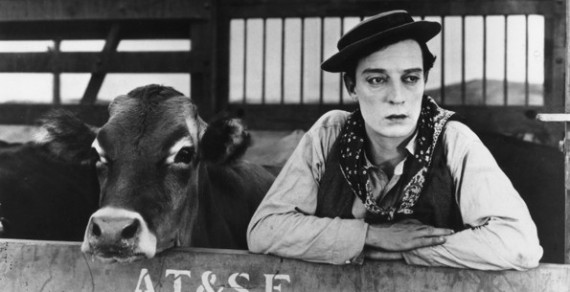

At the Movies

Besides Modern Times, there were other movies of note that were given rather scant attention in Mosher’s column, including the film adaptation of The Petrified Forest starring Humphrey Bogart, Bette Davis and Leslie Howard.

Robert E. Sherwood wrote the 1934 Broadway play of the same name, which was co-produced by Howard and featured both Howard and Bogart. When it was adapted to film, Howard insisted that Bogart appear in the movie, and it made Bogart a star (he remained grateful to Howard for the rest of his life).

Other cinema diversions included the musical Anything Goes, which included songs by Cole Porter; the comedy Soak the Rich, which featured a radical who falls in love with a rich man’s daughter; and a detective film, Muss ‘Em Up, with the usual movie gangsters.

* * *

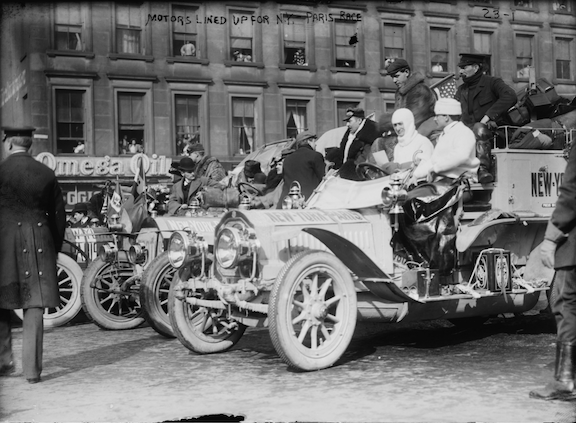

The Amazing Race

The New Yorker periodically featured “That Was New York,” which took a detailed look at significant events in the city’s history. In this installment, Donald Moffat recalled the 1908 New York to Paris automobile race, which commenced in Times Square on February 12 with six cars representing the U.S., France, Germany and Italy. It was an extraordinary event given that motorcars were a recent invention, and roads were nonexistent in many parts of the world. A brief excerpt:

* * *

Miscellany

Another regular feature in the early New Yorker was coverage of the New York Rangers, a team founded in 1926 by Tex Rickard after he completed construction of the third incarnation of Madison Square Garden. The Rangers were one of the Original Six NHL teams before the 1967 expansion, the others being the Boston Bruins, Chicago Blackhawks, Detroit Red Wings, Montreal Canadiens and Toronto Maple Leafs.

In this excerpt, the writer “K.B.” described the rough play against rival Detroit, which would win back-to-back Stanley Cups in 1936 and 1937.

* * *

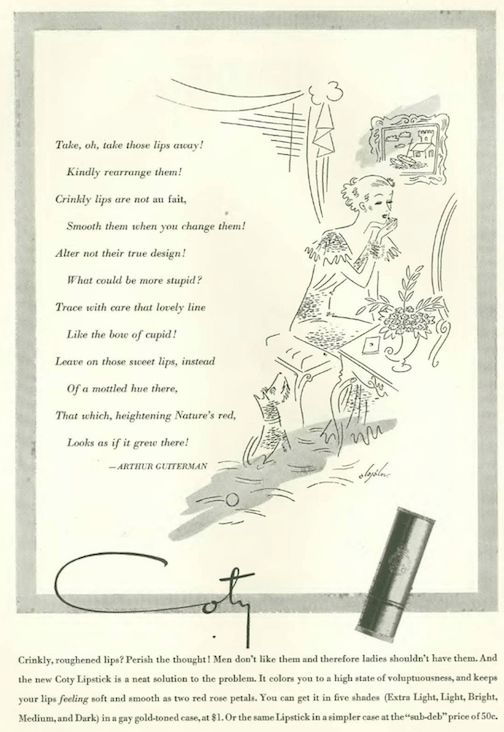

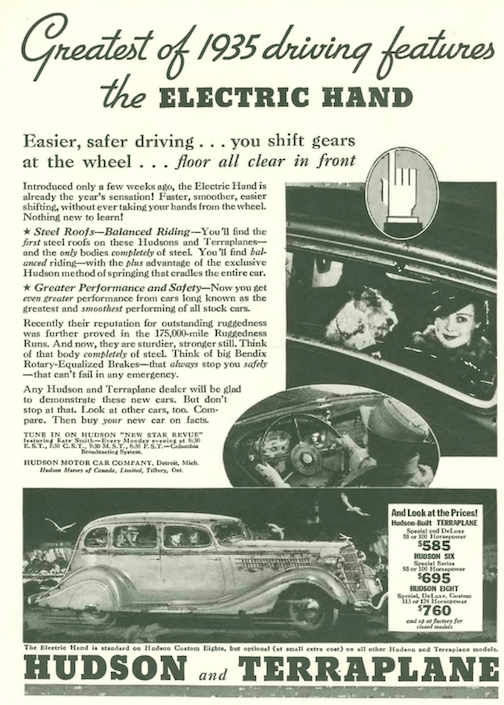

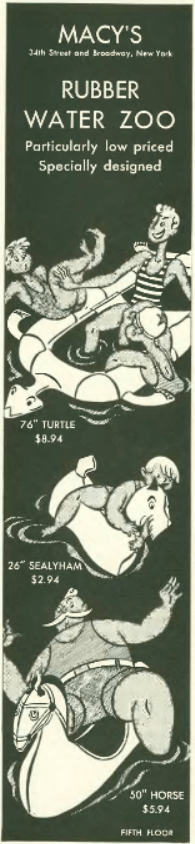

From Our Advertisers

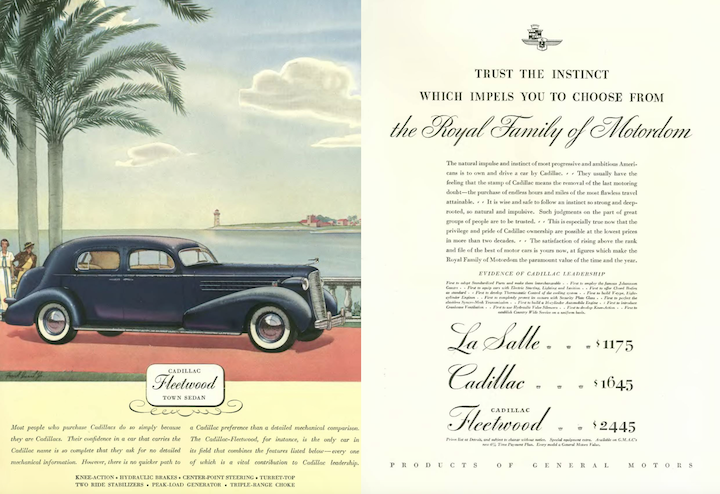

General Motors’ luxury car line offered three price points (and this lovely image) to weather the Depression years, ranging from the relatively affordable La Salle to the Cadillac Fleetwood…

…the Chrysler corporation took a different approach, deploying a very wordy full-page ad that referenced history (a Madame Curie analogy) and something called “Unseen Value” to move its line of autos…

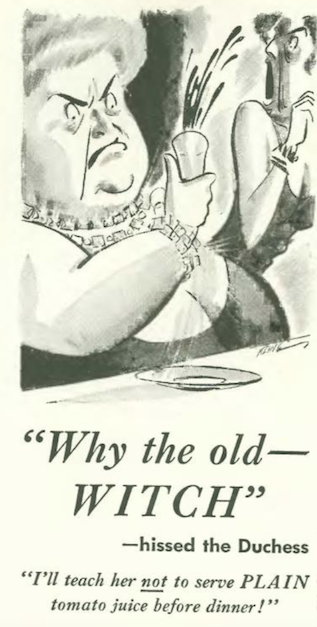

…the makers of College Inn Tomato Juice Cocktail brought back the “Duchess” with this shocking scene at the opera…

…recall last summer when College Inn featured the Duchess in a series of ads that illustrated her increasing fury over plain tomato juice…one wonders what sort of sadistic torment she had in mind for her hostess, “the old WITCH”…

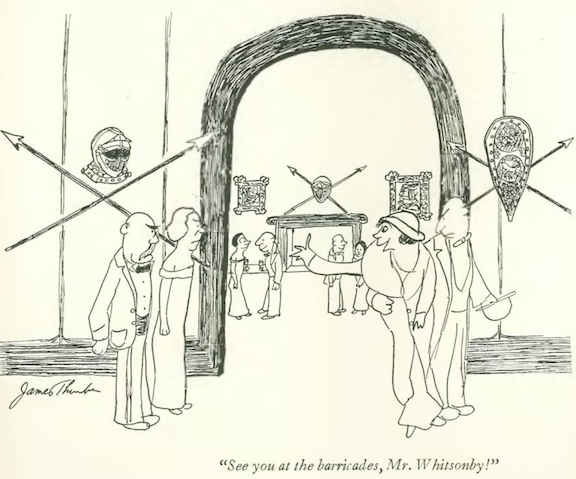

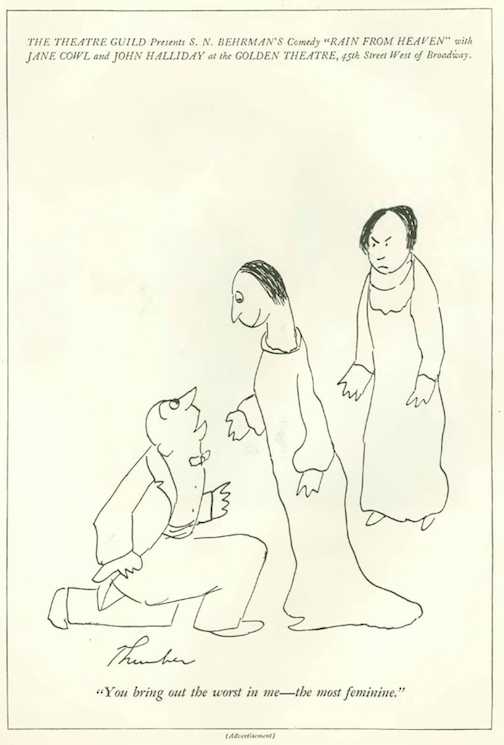

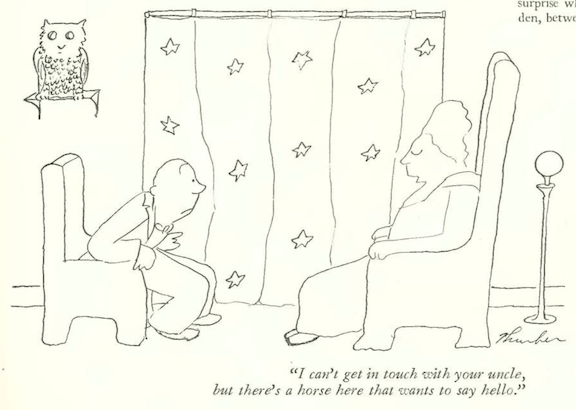

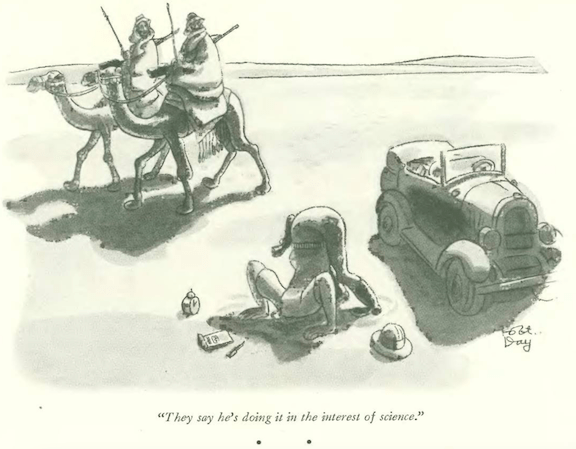

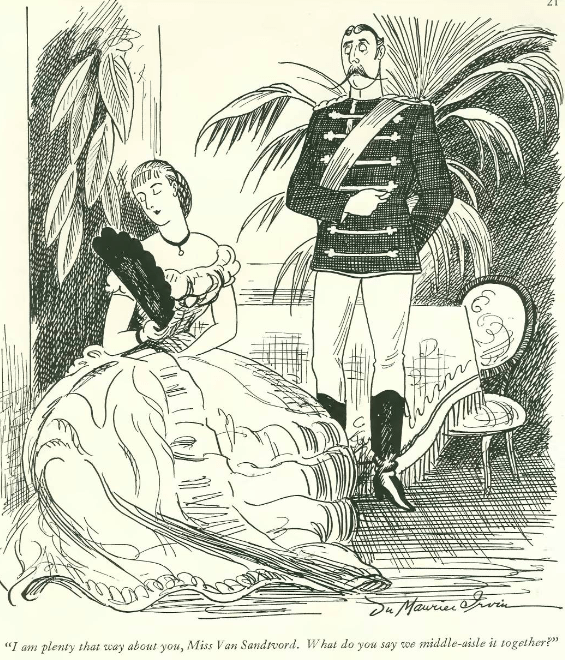

…on to our cartoonists, beginning with this spot by James Thurber…

…and Thurber again, with an unwanted call to solidarity…

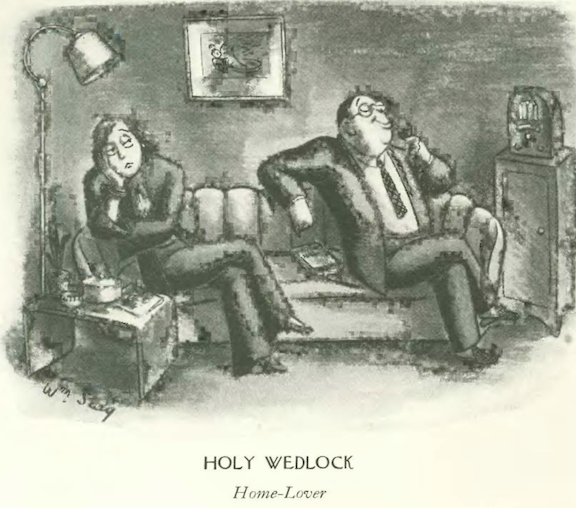

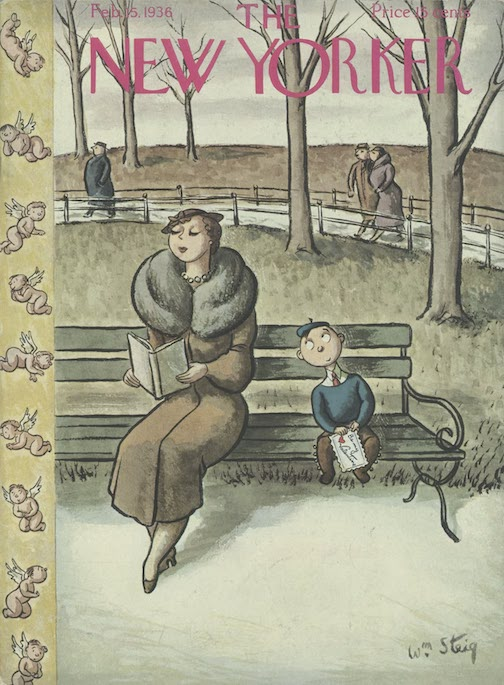

…William Steig explored marital bliss…

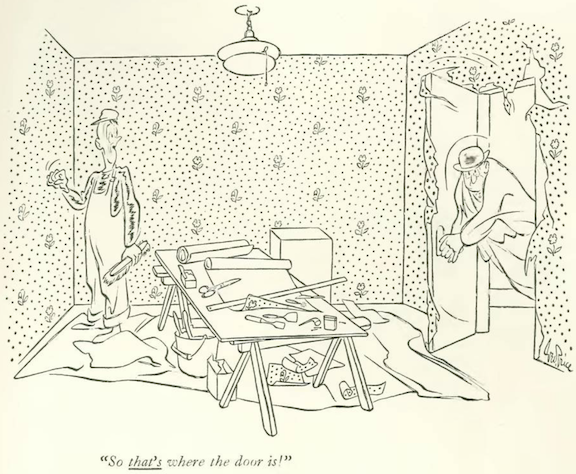

…George Price gave us a Three Stooges moment…

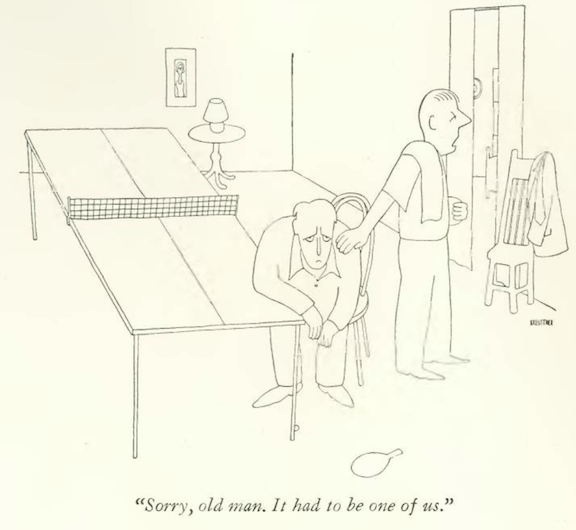

…I do not have the identity of this cartoonist…I will keep looking, but would love suggestions in the meantime…*update*…thanks to Frank Wilhoit for identifying the cartoonist below as John Kreuttner, also confirmed through Michael Maslin’s Ink Spill…

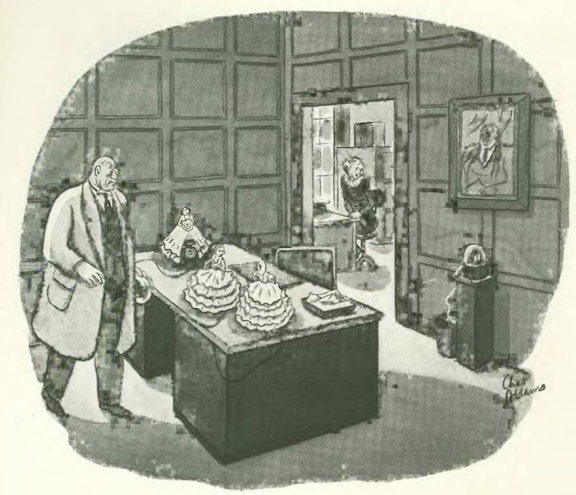

…Charles Addams added some frills to an executive suite…

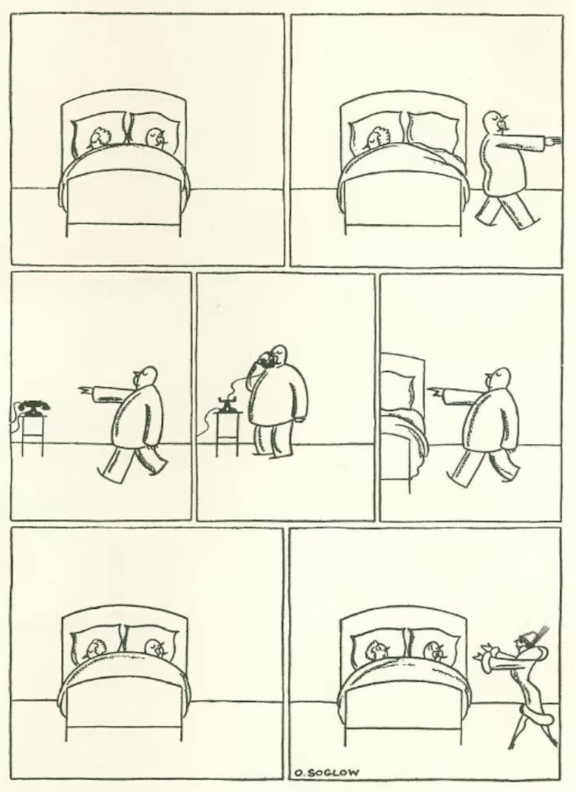

…Otto Soglow illustrated the hazards of sleepwalking…

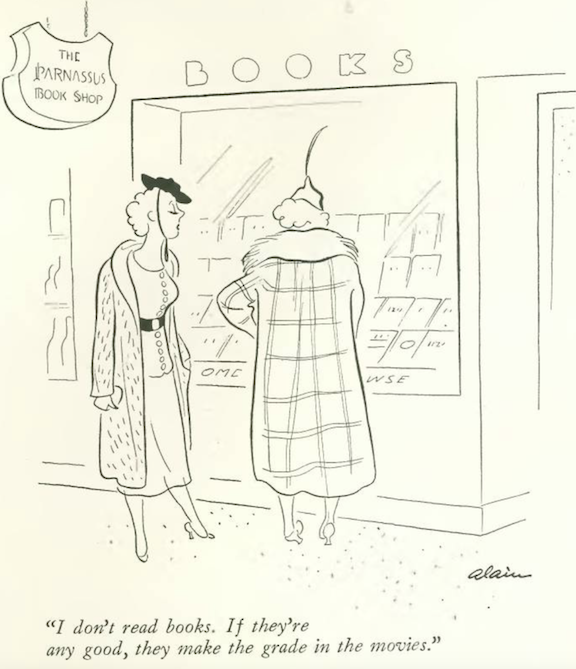

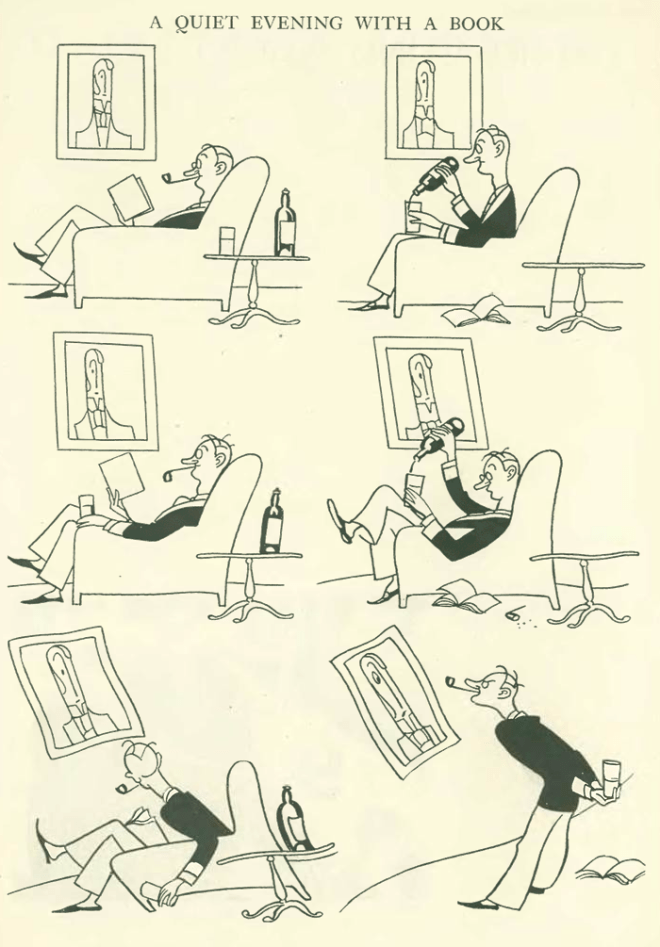

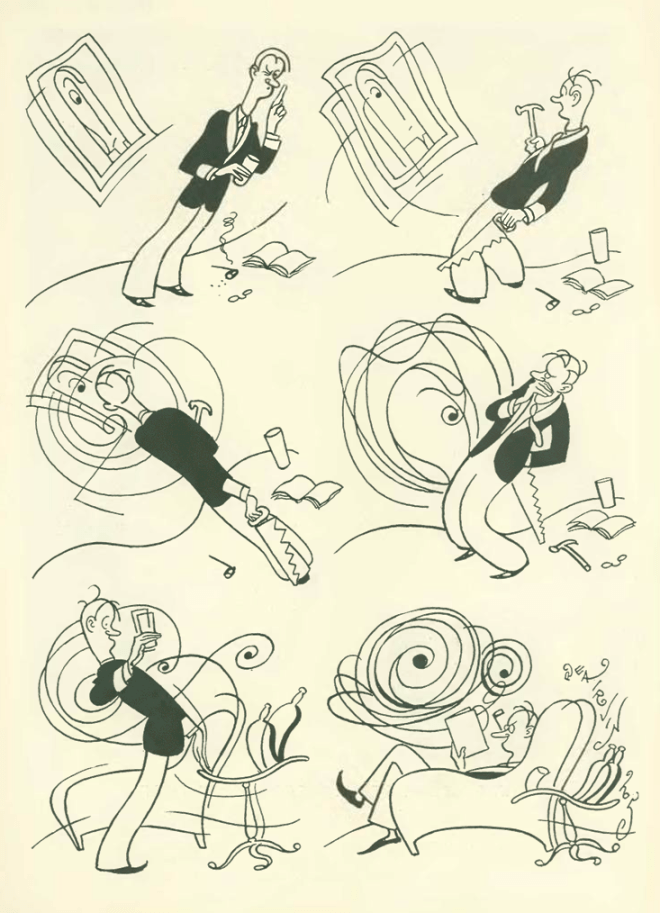

…Alain revealed a challenge to the publishing industry…

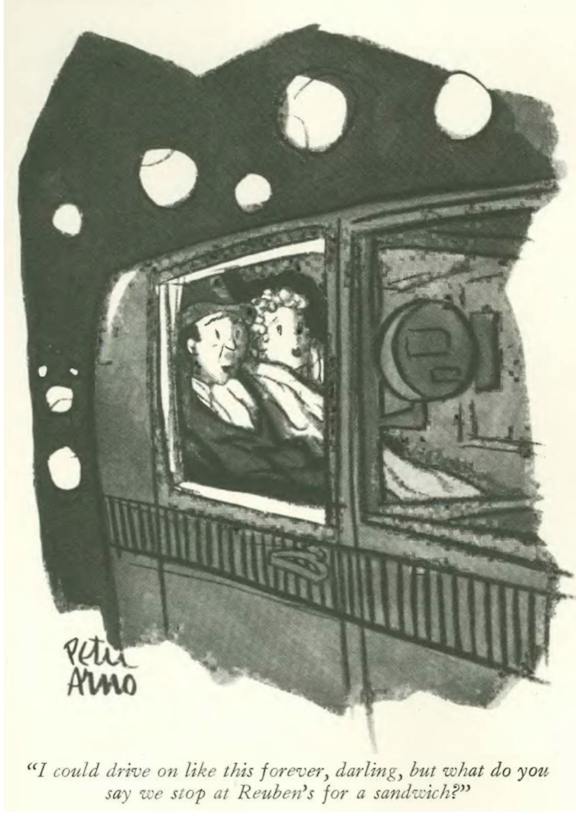

…Peter Arno possibly craved some sauerkraut and corned beef…

…William Crawford Galbraith was in familiar sugar daddy territory…

…Whitney Darrow Jr gave a nod to some homey surrealism…

…Barbara Shermund offered some well-weathered advice…

…and we close with Garrett Price, and a visitor more suited to Charles Addams…

Next Time: Comfort Food…