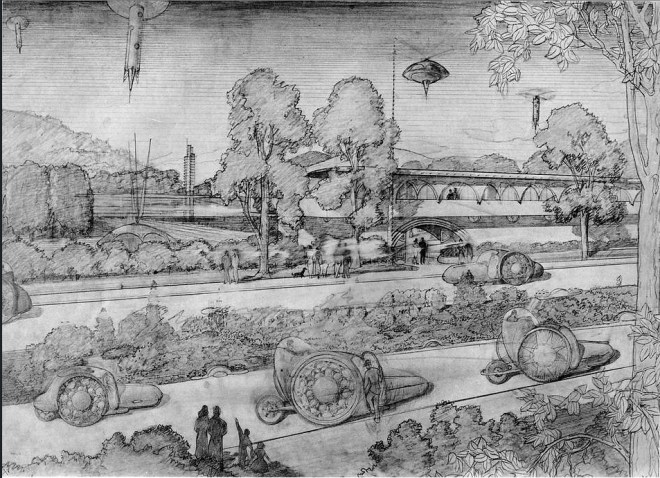

Above: Detail from Spanish architect David Romero's computer-generated model of Frank Lloyd Wright's Broadacre City, complete with an "aerotor" flying car.

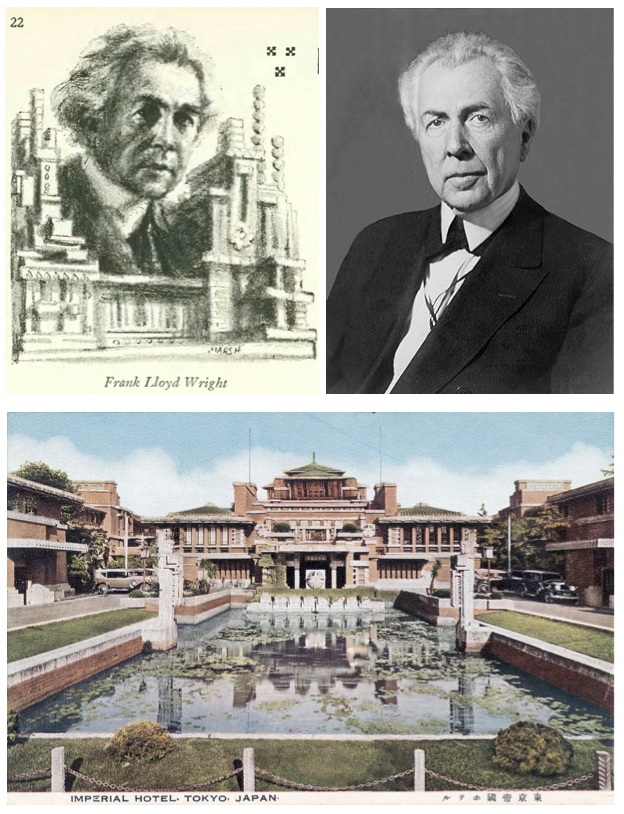

To be sure, architect Frank Lloyd Wright was a visionary, creating a uniquely American vernacular that influences architecture and design to this day. That might also true for his Broadacre City concept, which demonstrated how four square miles (10.3 km2) of countryside might be settled by 1,400 families. Wright unveiled this escape to the countryside in the middle of Manhattan.

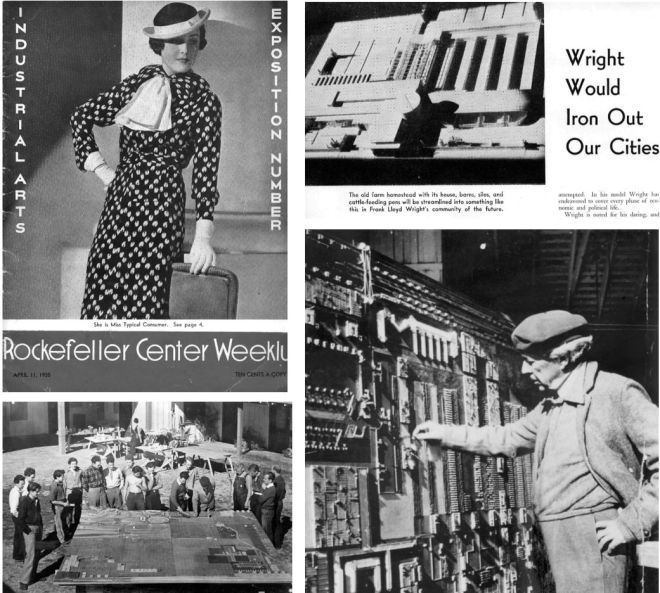

On April 15, 1935, the Industrial Arts Exposition opened at Rockefeller Center, and Wright (1867-1959) was front and center with his audacious proposal to resettle the entire population of the United States onto individual homesteads. Critic Lewis Mumford observed that Wright “carries the tradition of romantic isolation and reunion with the soil” by putting every American family on a minimum of five acres of land.

Wright first presented the idea of Broadacre City in his book The Disappearing City in 1932…

…note how the above drawing is reflected in one of Wright’s last designs, the Marin County Civic Center:

A detailed 12×12-foot scale model of Broadacre City—crafted by Wright’s student interns at Taliesin, was unveiled at the Industrial Arts Exposition:

For the most part Mumford reacted favorably to Wright’s vision, which is no surprise considering that Mumford derided the dehumanizing skyscrapers popping up all over his city (including Rockefeller Center).

Despite his patrician demeanor, Wright envisioned an egalitarian Broadacre City, with every family having access to cars, telephones and other appliances. Power would come from solar and electric energy, and any technological advances would be applied at a local level toward the common good.

What Mumford (and perhaps Wright) didn’t fully anticipate was the urban sprawl such a vision would help inspire, the suburban and exurban landscape that would lead to a car-dominated world of congested, multi-lane highways and housing developments that continue to encroach on our woodlands and wetlands. And we didn’t get those groovy aerotors either.

* * *

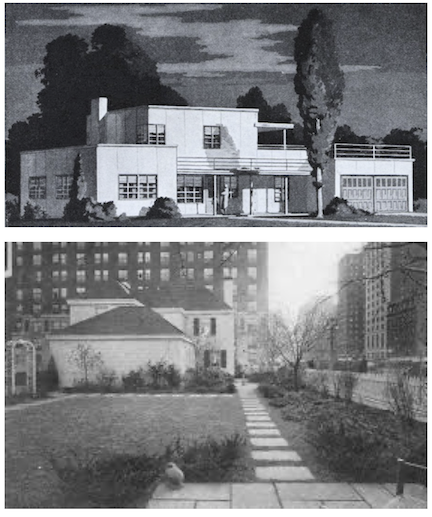

Little House on the Avenue

E.B. White, in his “Notes and Comment,” also offered some observations on housing trends, noting the manufactured “Motohome” displayed at Wanamaker’s as well as “America’s Little House,” plopped down at the corner of 39th and Park Avenue.

* * *

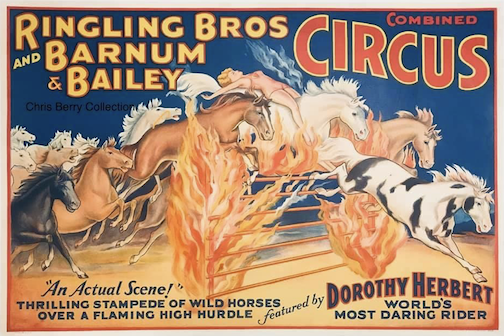

Horsing Around

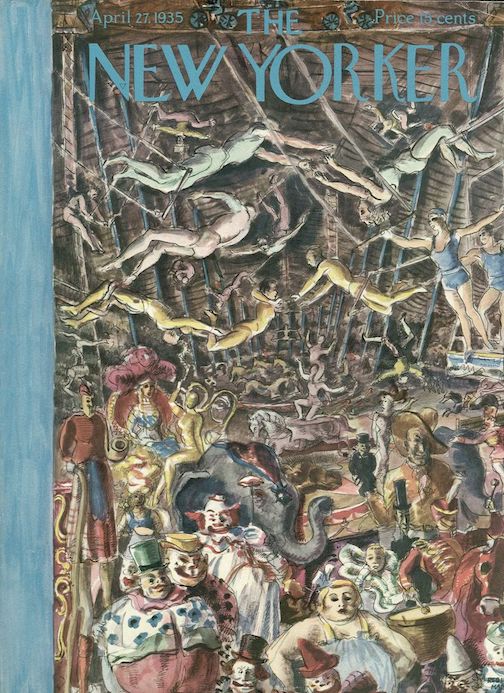

Although known for their nonchalance, New Yorkers could still find some enthusiasm when the circus came to town. “The Talk of the Town” looked in on the star of the circus, Dorothy Herbert (1910-1994), a trick rider with the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus.

* * *

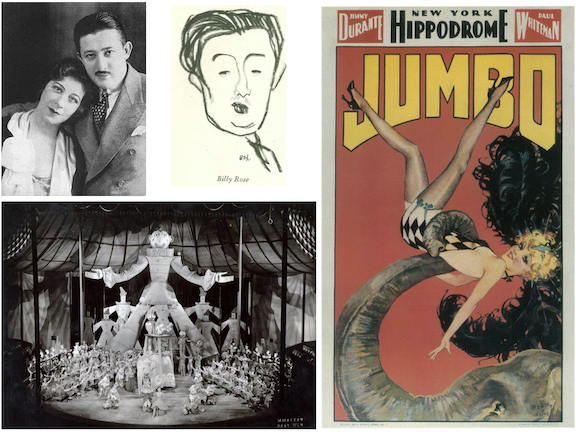

Don’t Call Him ‘Tiny’

He was known as “The Little Napoleon of Showmanship,” but there was nothing small about Billy Rose’s accomplishments as an impresario, theatrical showman, composer, lyricist and columnist. Here are excerpts from Alva Johnston’s profile:

* * *

On Guard

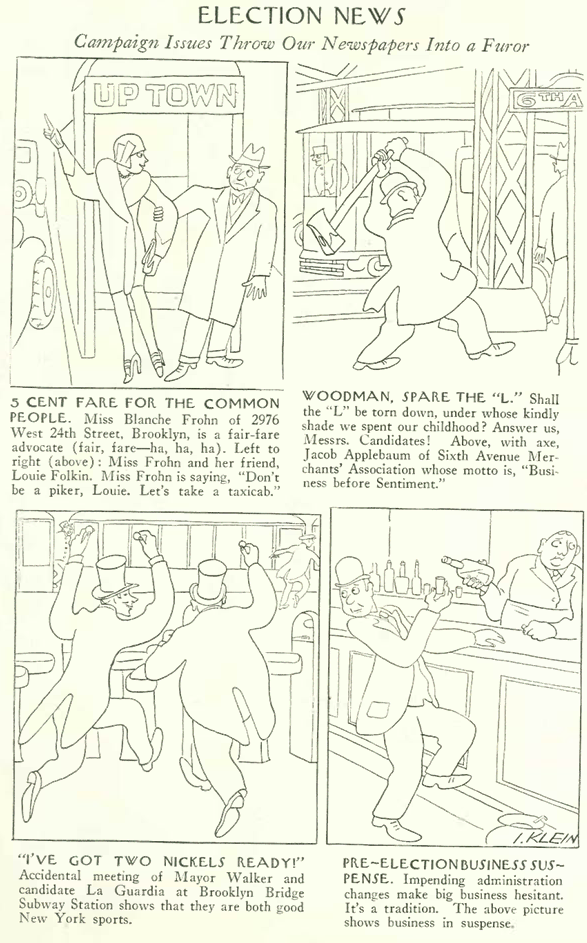

We shift gears and turn to more sobering events of the 1930s, namely the rise of fascism in Europe. In his column “Of All Things,” Howard Brubaker pondered the possibilities of fascism in his own country…

…meanwhile, Paris correspondent Janet Flanner was finding nothing funny about the uneasy calm among Parisians as war with Germany seemed likely.

Flanner also remarked on Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will). Flanner’s assessment of this “best recent European pageant” wryly underscored the horrors the film portends.

* * *

News From An Old Friend

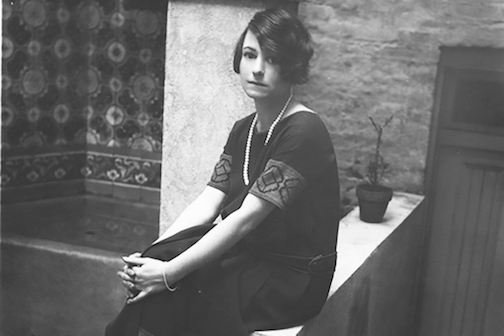

Longtime readers may recall one of my earliest entries on Queen Marie of Romania (1875-1938); the March 14, 1925 edition of The New Yorker (issue #4) found New Yorkers “agog” over her planned 1926 visit to the city. Her comings and goings were followed for a time (she also appeared in a Pond’s Cold Cream ad in the June 6, 1925 issue), but then she abruptly disappeared. Here she is again, courtesy of a glowing book review by Clifton Fadiman. An excerpt:

* * *

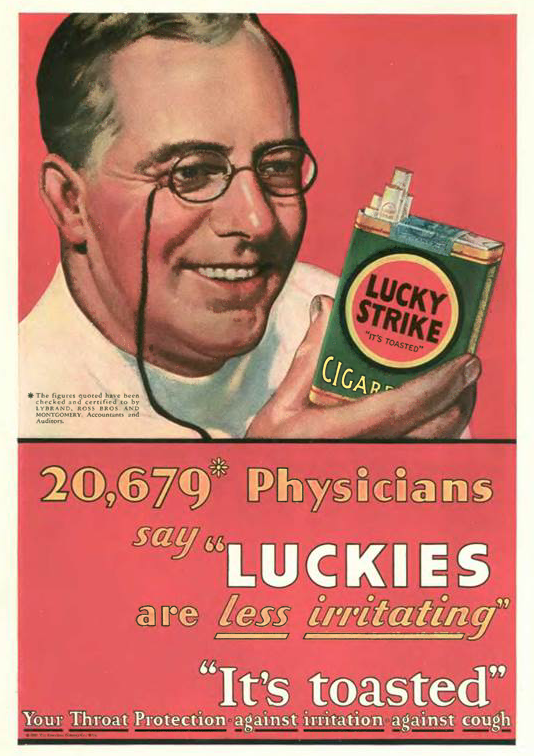

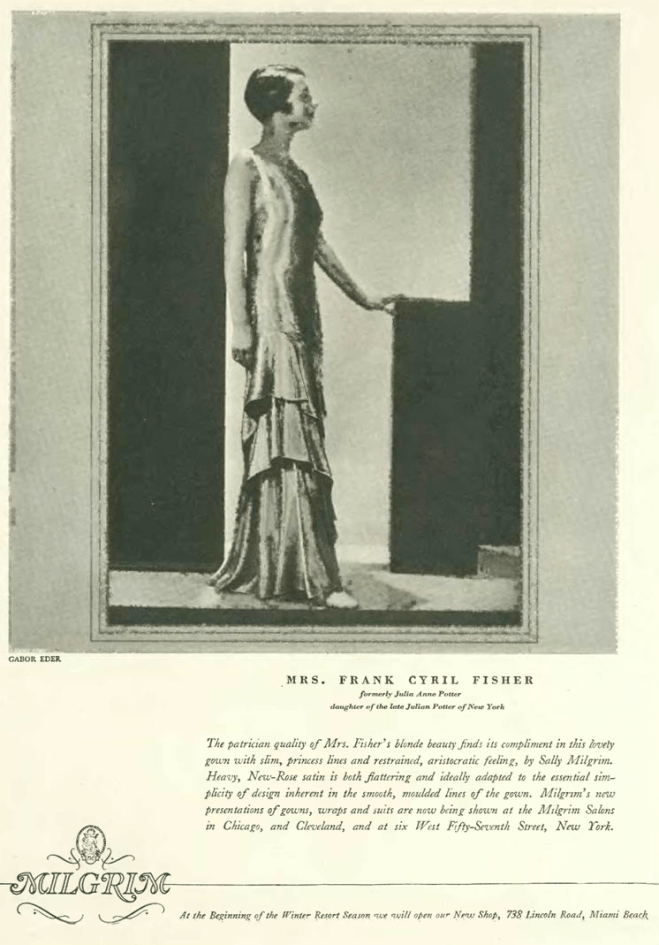

From Our Advertisers

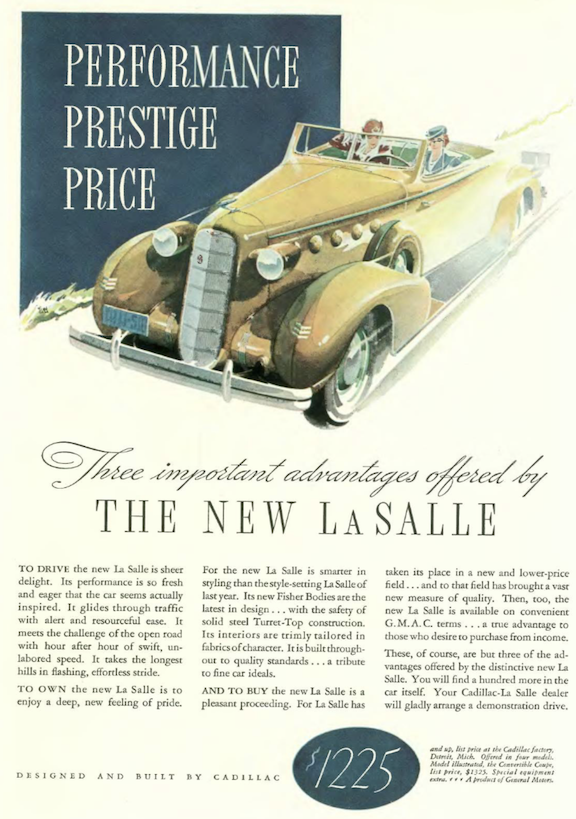

Although we’ve seen plenty of ads from prestige automakers such as Packard, it was clear that companies found their sweet spot in lower-priced models that still suggested “prestige”…here’s an example from Cadillac’s budget line LaSalle…

…for less than half the price of a LaSalle you could get behind the wheel of Hudson, its makers suggesting that prestige doesn’t preclude thrift…this ad seems to have been hastily produced–note the right side of ad, with just a slice of some toff squeezed next to the copy…

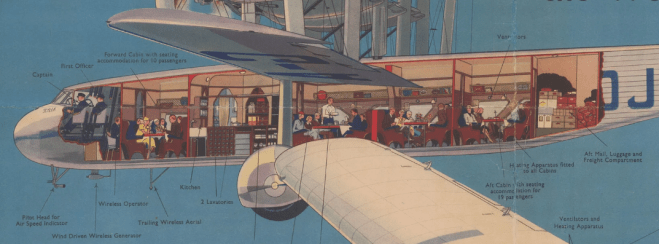

…this advertisement would only appeal to those who were among the tiny minority who could afford to fly…from 1924 to 1939 this early long-range airline served British Empire routes to South Africa, India, Australia and the Far East…

…for reference, detail below of a Scylla-class airliner used by Imperial Airways…

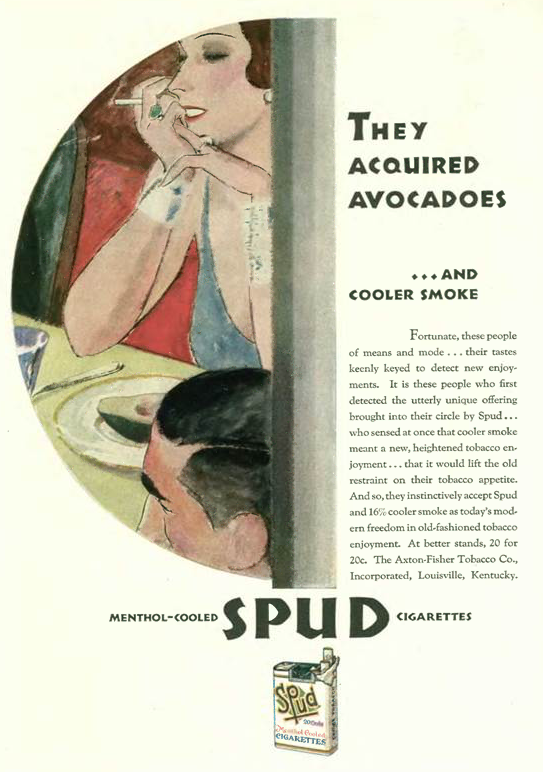

…and what would the back cover be without a photo of a stylish woman having a smoke?…

…a few advertisers referenced the circus in town to drum up business…

…and we segue to our cartoonists and illustrators, and this circus-themed spot from an illustrator signed “Geoffrey”…

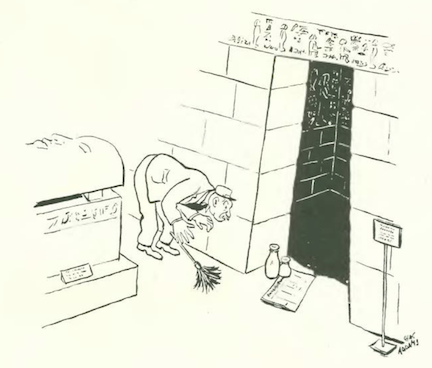

…a more familiar name is found at the bottom of page 4…namely Charles Addams…the milk order outside the tomb hints at things to come…

…Addams again, going from Bacchus to beige…

…George Price, and well, you know…

…Robert Day was aloft with a speculative builder…

…William Steig typecast his Small Fry…

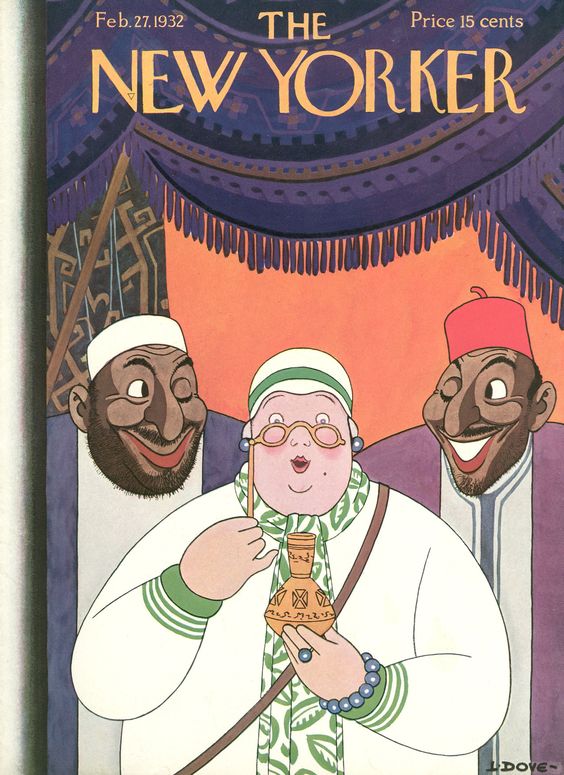

…Leonard Dove made a sudden exit…

…Gilbert Bundy found one old boy unaffected by spring fever…

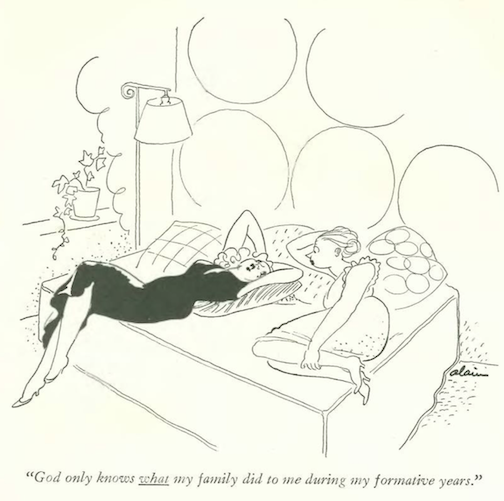

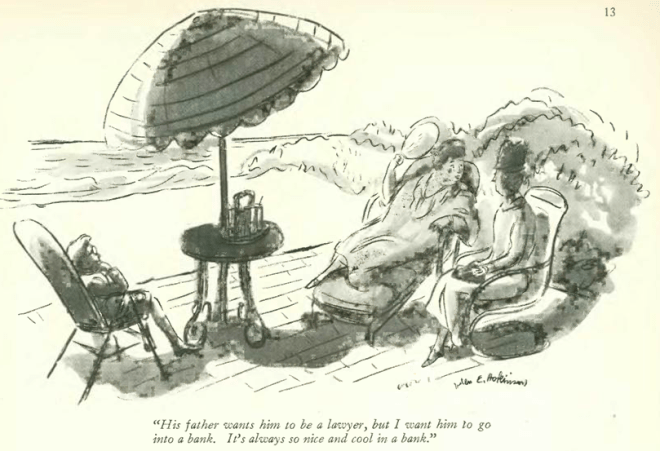

…Alain channeled Barbara Shermund to give us this gem…

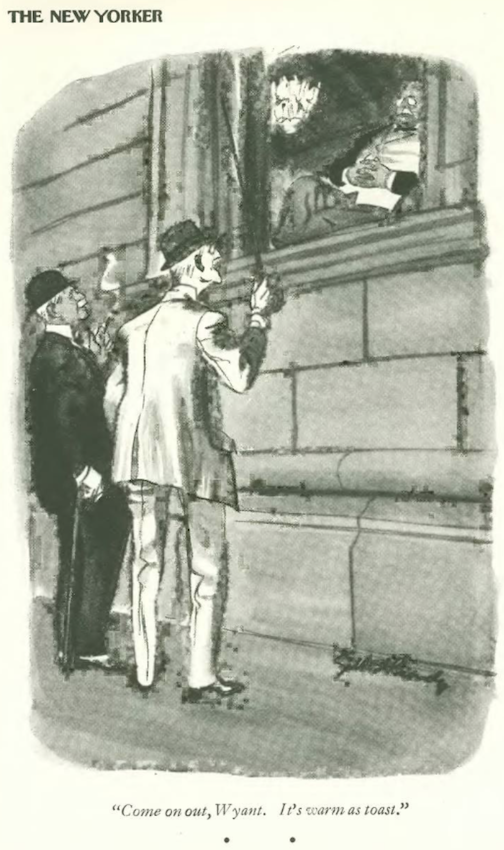

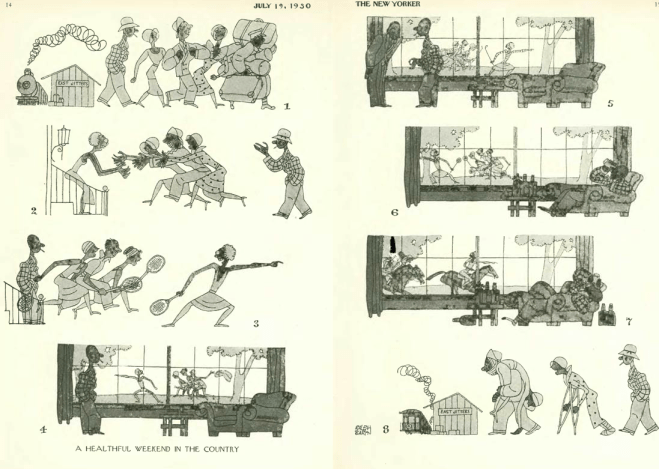

…and we close with a typical day in James Thurber’s world…

Next Time: The Royal Treatment…