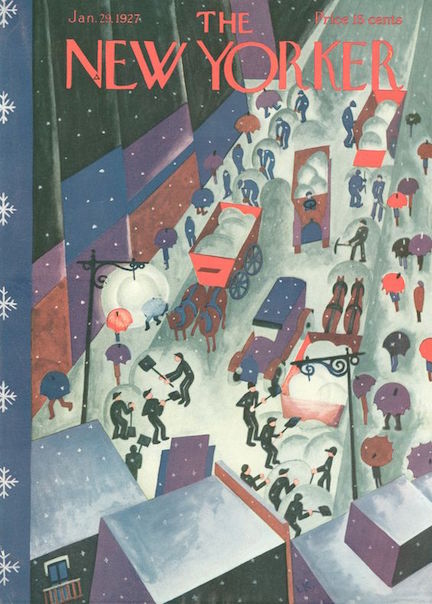

The New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” editors were always in search of something to amuse, and in the Jan. 29, 1927 issue they found it in one Maurine Watkins, who wrote the Broadway hit musical Chicago (yes, THAT one) while still enrolled in her drama class at Yale:

Watkins transformed a brief career as a Chicago Tribune crime reporter into her Broadway success, thanks to her fondness for writing about murderers:

Chicago opened on Broadway in late December 1926 at the Sam Harris Theatre, where it ran for 172 performances. Watkins wrote the play as “homework” for her Yale drama class:

It didn’t take long for Hollywood to come calling, with Cecil B. DeMille producing a silent film version (directed by Frank Urson) in 1927.

Watkins would go on to write about twenty plays, moving on to Hollywood to write screenplays including the 1936 comedy Libeled Lady. She left Hollywood in the 1940s to be close to her parents in Florida. A lifelong Christian, Watkins spent much of her fortune funding the study of Greek and the Bible at some twenty universities, including Princeton. Following her death in 1969, her estate sold the rights to Chicago to famed choreographer and director Bob Fosse. Fosse would go on to develop Chicago: A Musical Vaudeville in 1975, which was revived in 1997 and turned into an Academy Award-winning film in 2002.

* * *

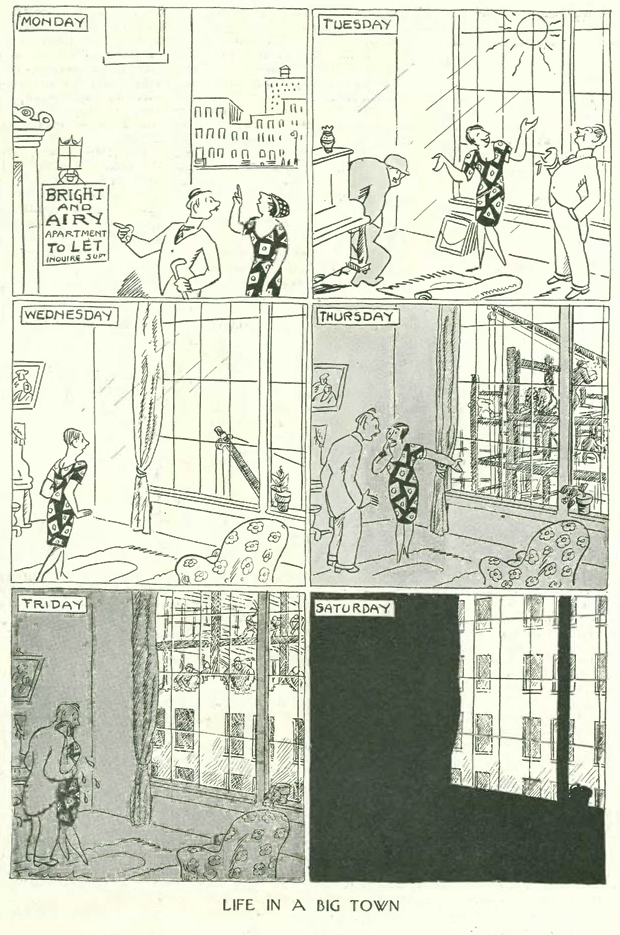

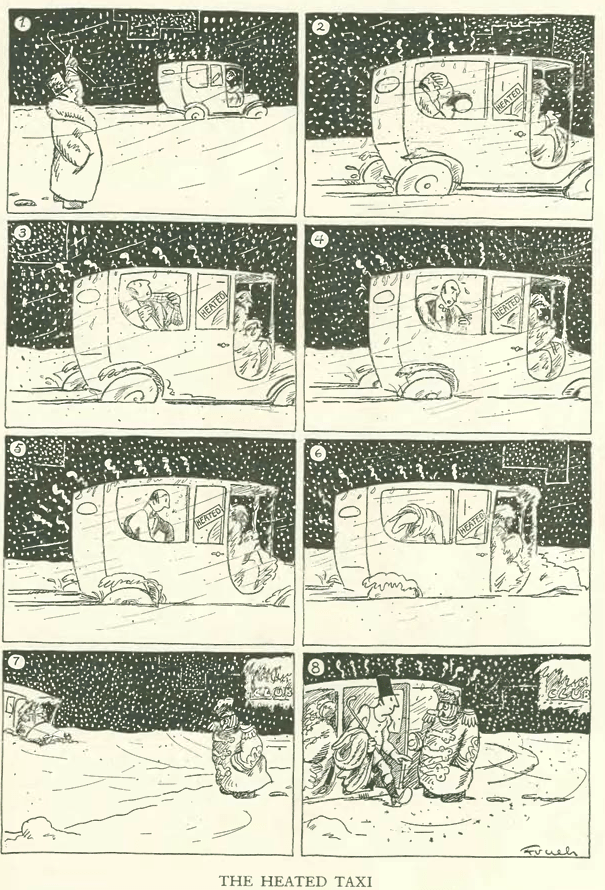

Winter doldrums had set into city, which was digging out of the latest snowstorm and leaving the “Talk” editors pining for spring.

So it was unwelcome news that the green lawns along Cottage Row were to become the latest casualties of the booming city:

According to the excellent blog Daytonian in Manhattan, around 1848 William Rhinelander filled the 7th Avenue block between 12th and 13th Streets with eleven three-story homes above “English basements.” The simple residences were intended for middle-class families and sat more than twenty feet back from the street, providing grassy lawns and garden space. During summer weather each floor had a deep veranda that provided shade and caught cooling breezes.

As it turned out, the green lawns won a brief reprieve: By the time developers got around to building an apartment on the site, the Depression hit and left Cottage Row standing for another ten years. It was demolished in 1937, replaced not by an apartment building but rather by a gas station and used car lot, which were replaced in 1964 by the Joseph Curran Building (now the Lenox Hill Healthplex):

* * *

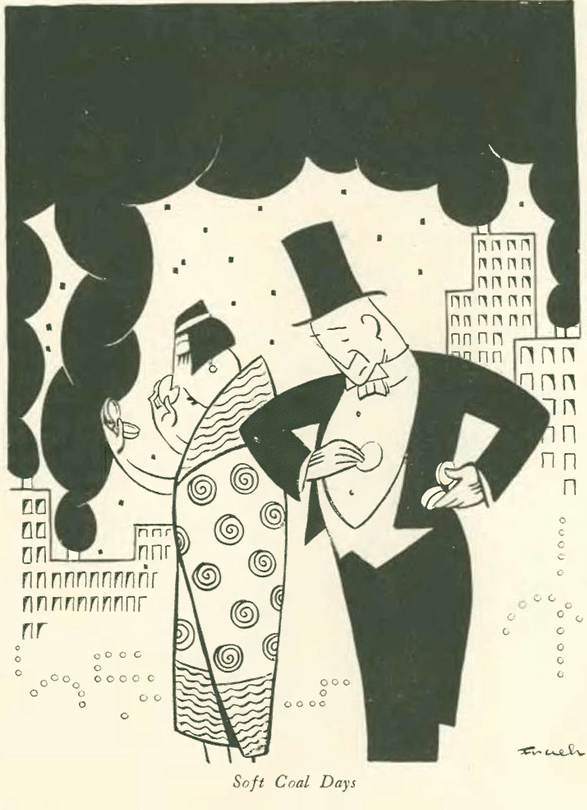

The winter drear was further compounded by the sooty smog that lingered over the city, fed by so many coal-fired furnaces. The “Talk” editors noted:

To read more about “soft coal days,” see my previous post, “A Fine Mess.”

* * *

Columnist Lois Long (“Tables for Two”) was contemplating dance lessons to learn the “Black Bottom,” the dance craze that supplanted “The Charleston” in 1926.

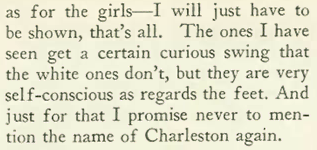

Apparently the dance called for special shoes, per this advertisement from the same issue:

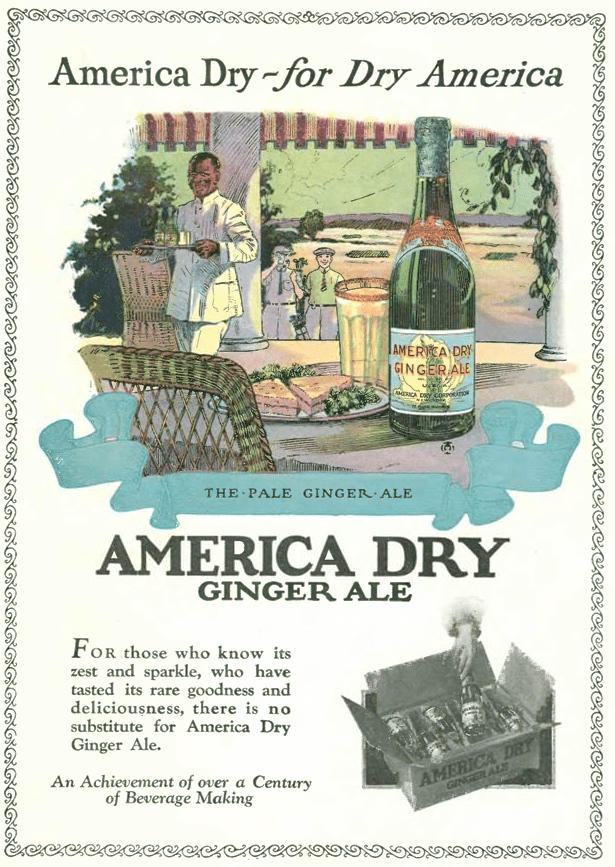

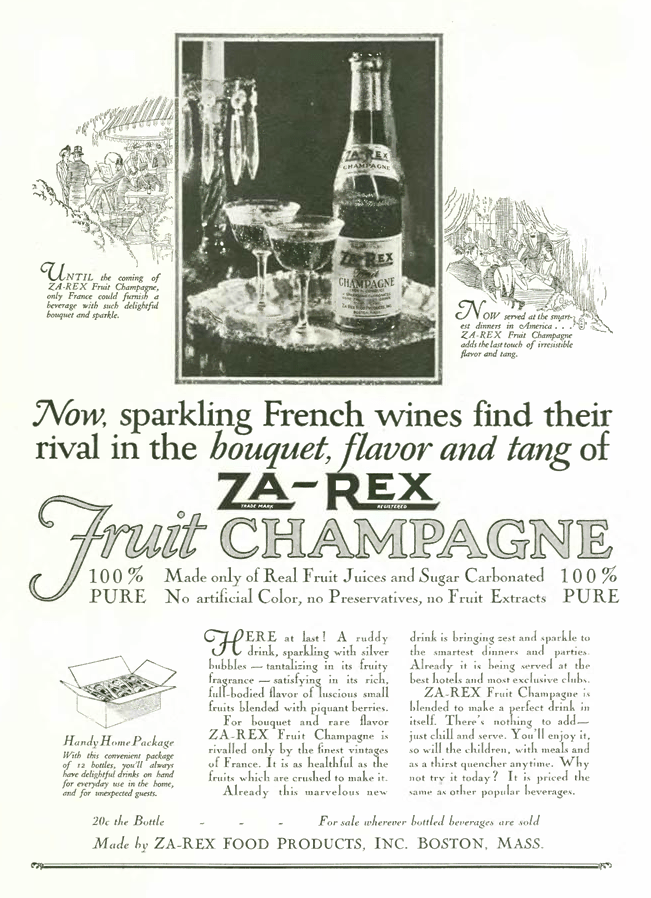

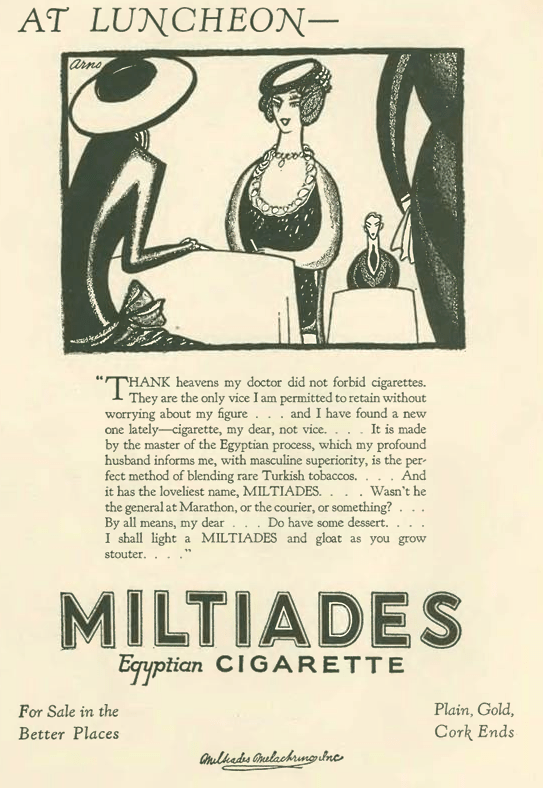

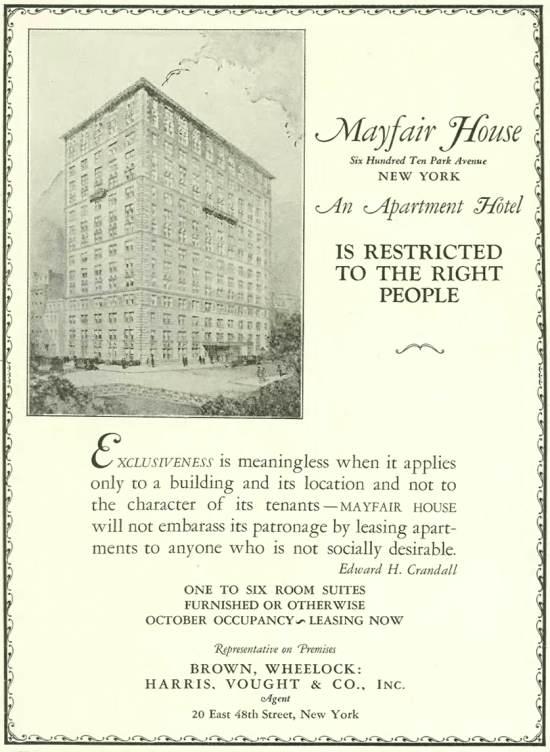

Up to now I’ve been posting images of often lavish ads featured mostly in the first sections of the magazine and on the front and back inside covers, but there were other, less expensive (and less artful) ads sprinkled in the back pages of the magazine, a tradition that continues to this day:

Next Time: Spring Fever…