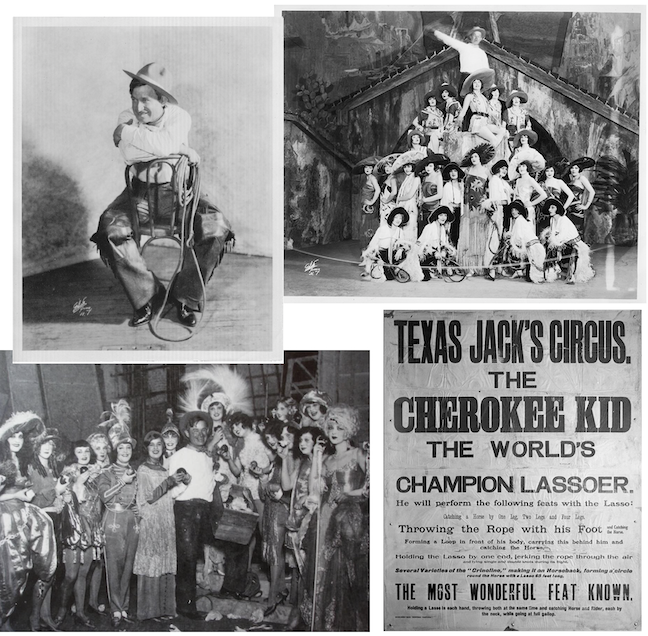

William Penn Adair Rogers, aka Will Rogers (1879–1935), was a man of many talents. Today he is mostly referred to as a humorist, but he was also an actor, a social and political commentator, a trick roper and a vaudeville performer. To Americans he was a national icon.

Rogers was also internationally famous, having traveled around the world three times and appearing in 71 films (50 of those silent). He also wrote more than 4,000 newspaper columns—nationally syndicated by The New York Times—that reached 40 million readers, and there were also magazine articles, radio broadcasts and personal appearances. He seemed to be everywhere.

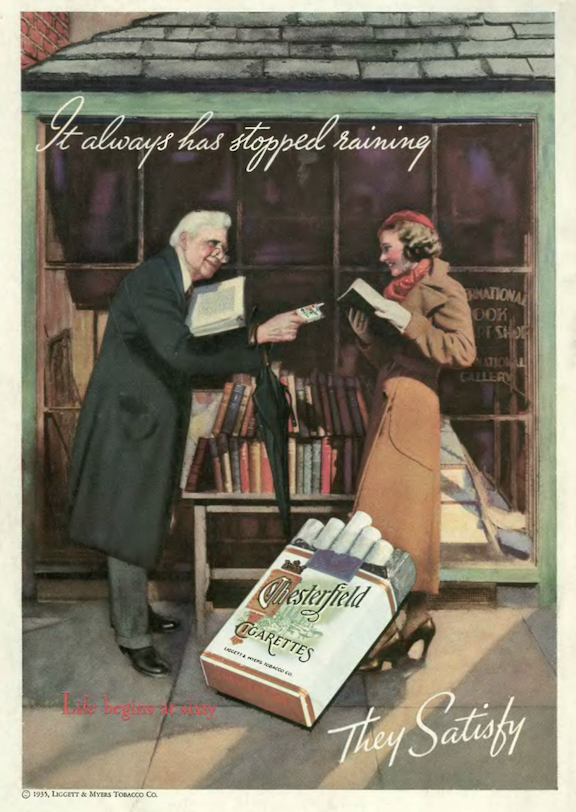

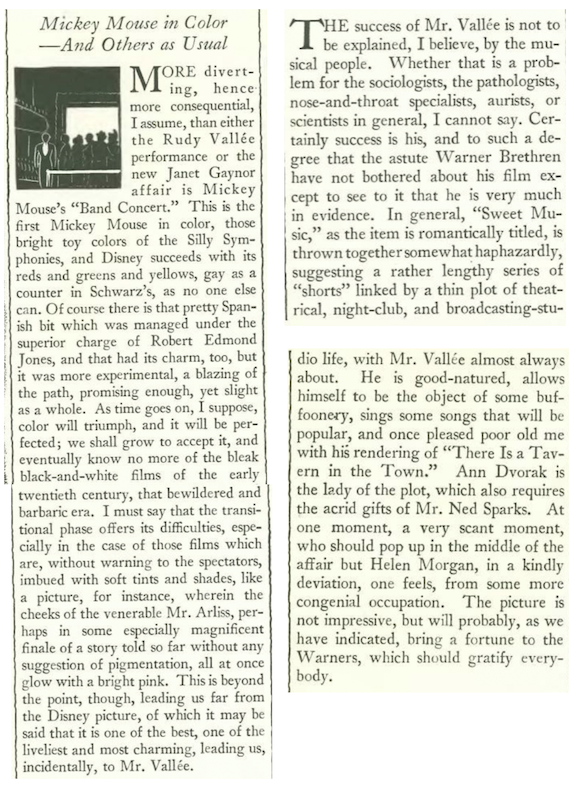

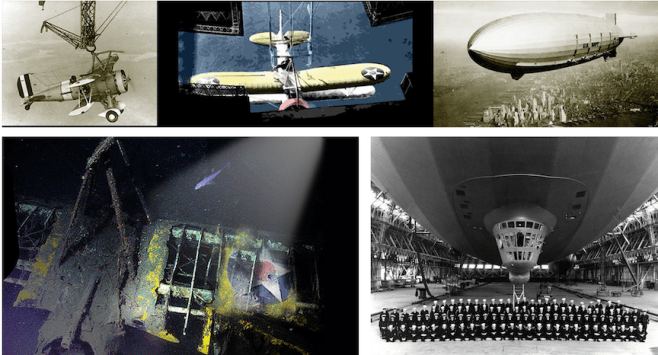

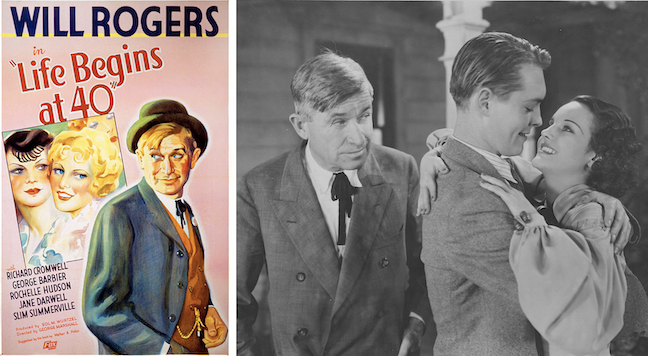

When John Mosher reviewed Rogers’ latest film, Life Begins At Forty, he found it to be one of Rogers’ best. It would also prove to be one of his last. On August 15, 1935, a small airplane carrying Rogers and aviator Wiley Post would crash on takeoff near Point Barrow, Alaska, claiming the lives of both men. Rogers would appear in three more films in 1935, the last two posthumously.

* * *

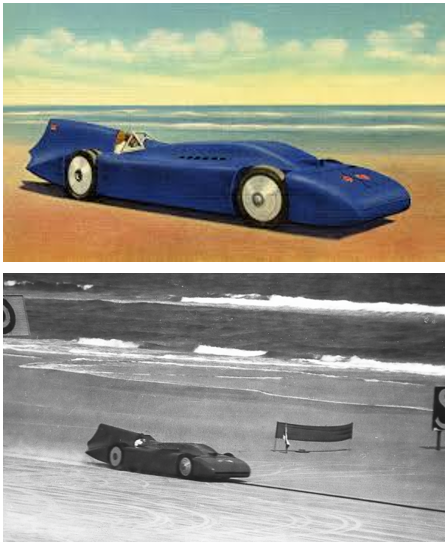

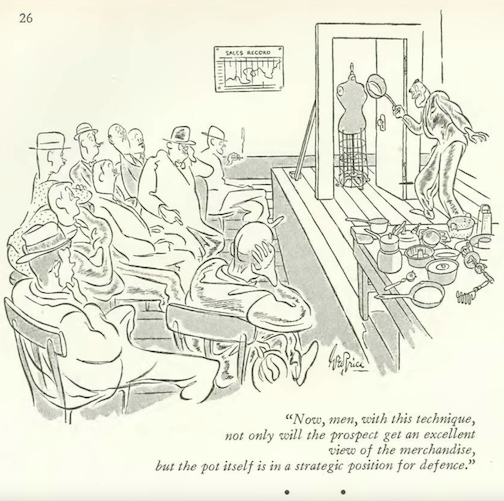

Not Toying Around

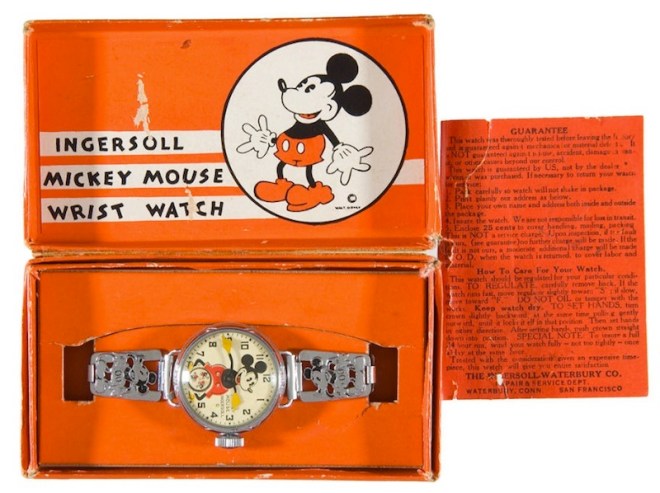

“The Talk of the Town” looked in on the serious business of toymakers, with 1935 being the year of streamlined tricycles, Buck Rogers disintegrator pistols, and, of course, Shirley Temple dolls.

* * *

Literary Spirits

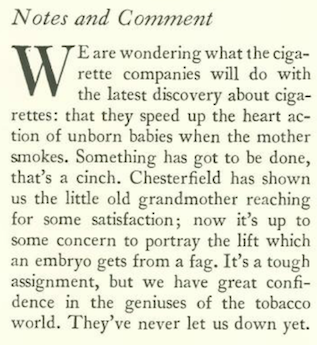

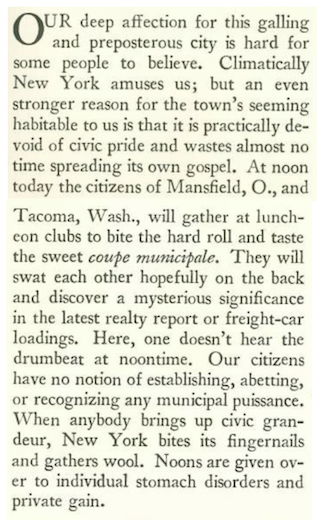

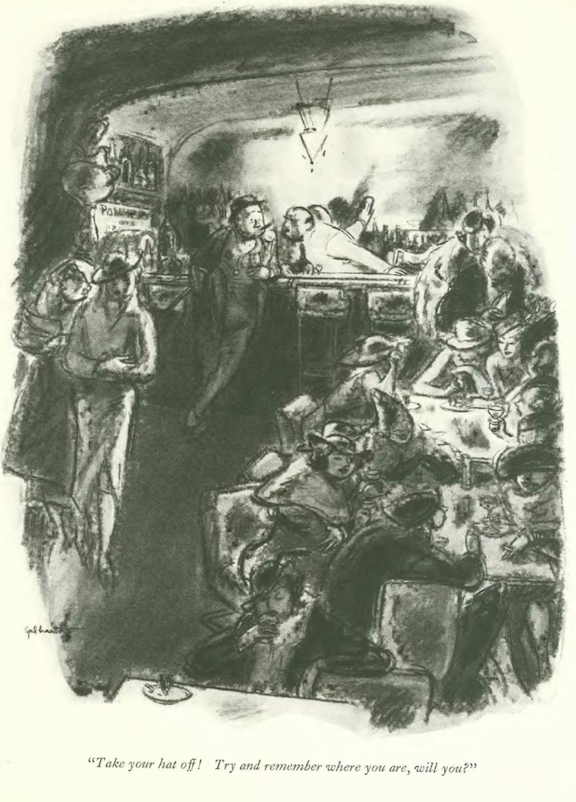

E.B. White welcomed the return of literary tea party, which thanks to the repeal of the 18th Amendment had been re-dubbed the “literary cocktail party.” He shared his thoughts in “Notes and Comment”…

* * *

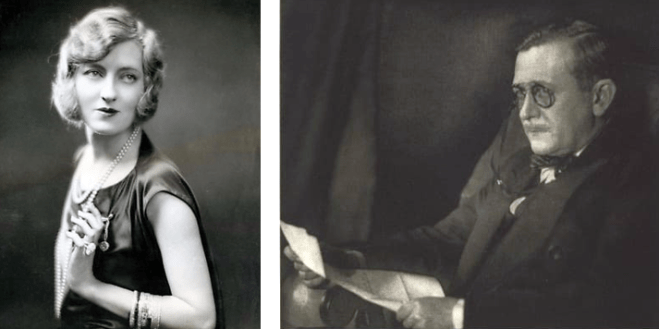

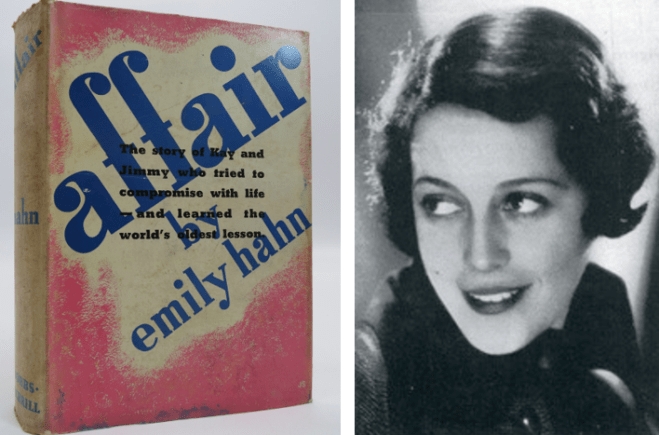

Proto Feminist

Emily Hahn was one of the more lively figures in The New Yorker’s stable of journalists and writers, leading an adventurous life that included a hike across Central Africa in the 1930s and getting into all kinds of trouble during the Japanese invasion of China. According to Roger Angell, Hahn was, “in truth, something rare: a woman deeply, almost domestically, at home in the world. Driven by curiosity and energy, she went there and did that, and then wrote about it without fuss.” It is no surprise that Hahn’s latest novel, Affair, didn’t shy away from topics like abortion. According to reviewer Clifton Fadiman, the novel’s “anonymous grayness” exposed the banality of love in the twentieth century.

If Hollywood is looking for a new biopic, Hahn would make a fascinating subject (Kristen Stewart would be perfect for the part). According to IMDB, there is an “Untitled Emily ‘Mickey’ Hahn Project”—a TV series—that has been in development since 2022, but so far nothing has come of it.

* * *

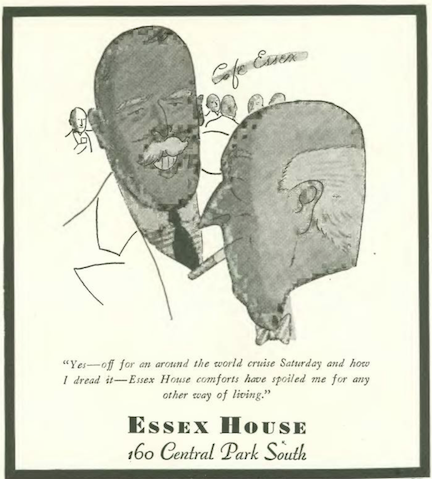

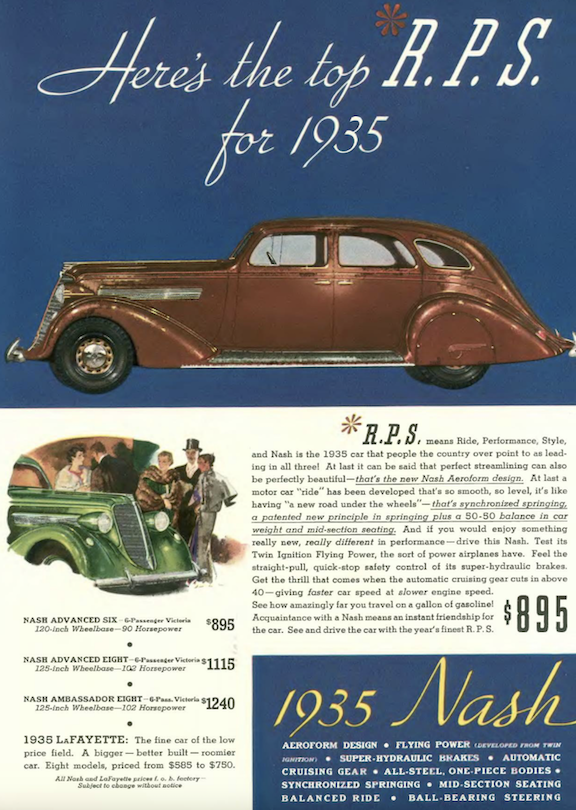

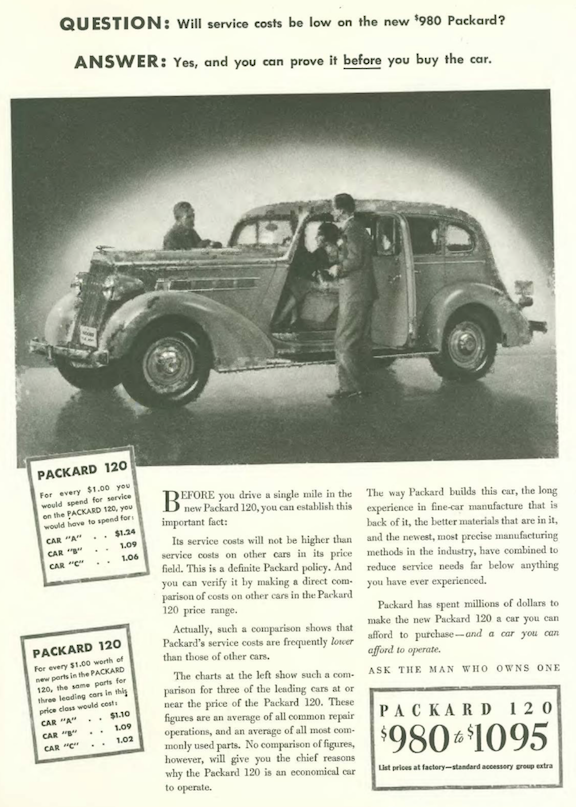

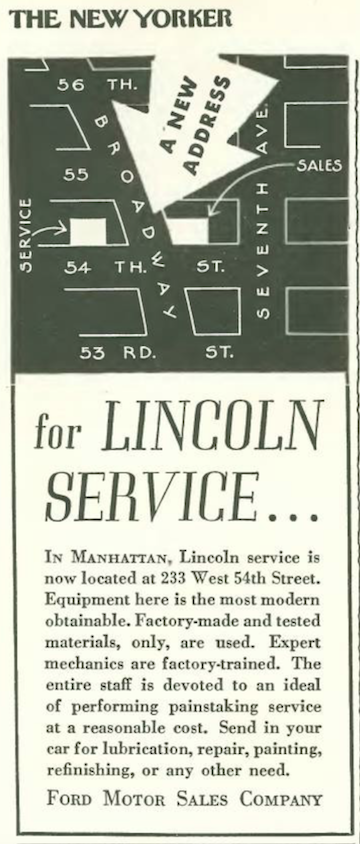

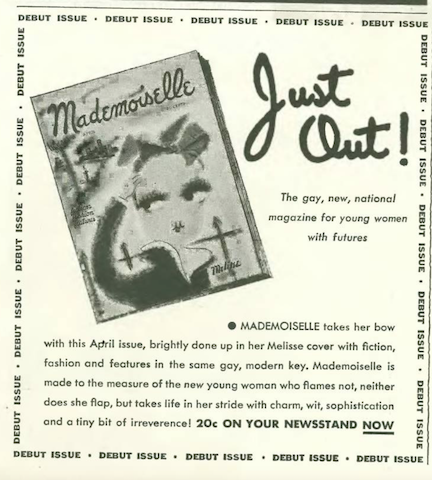

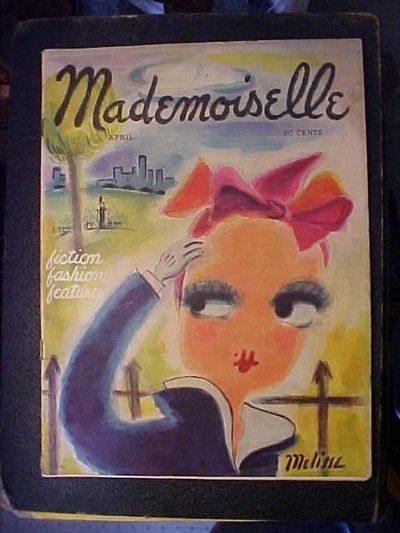

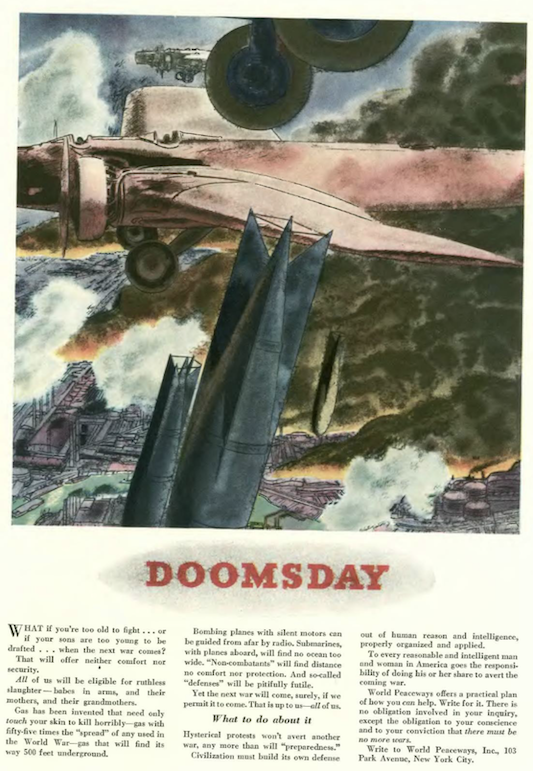

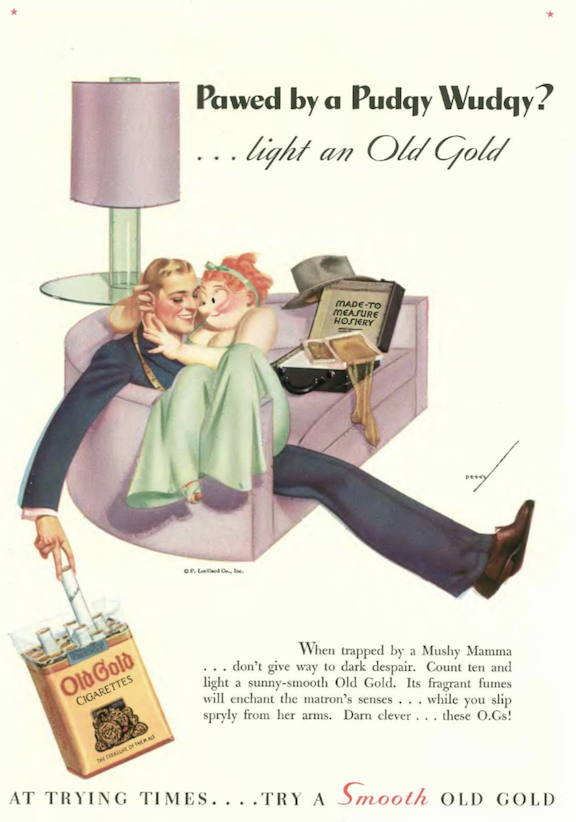

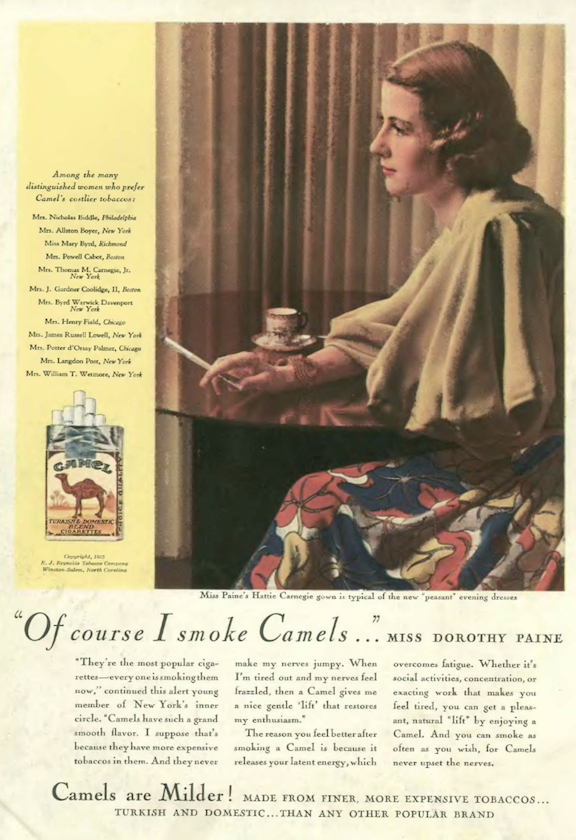

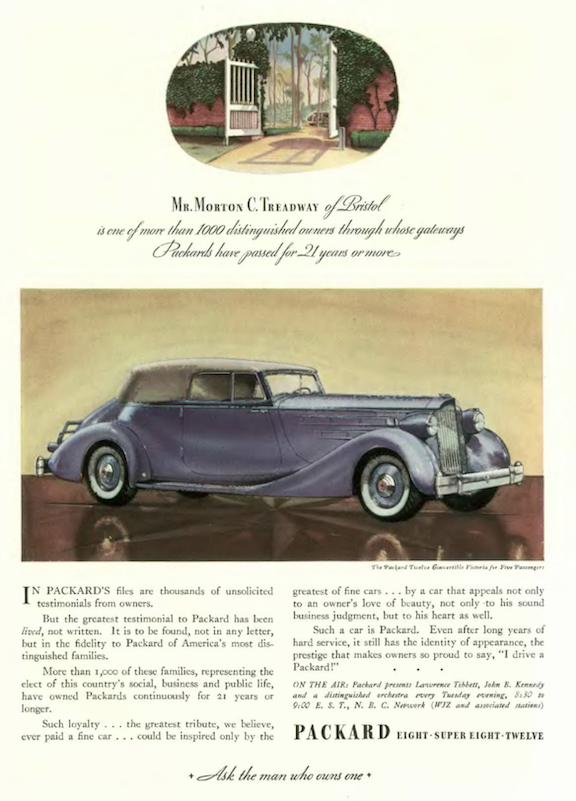

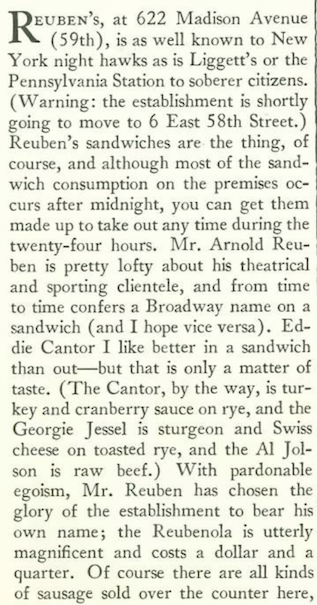

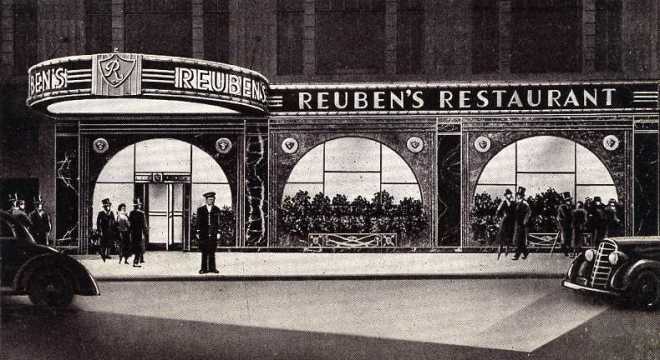

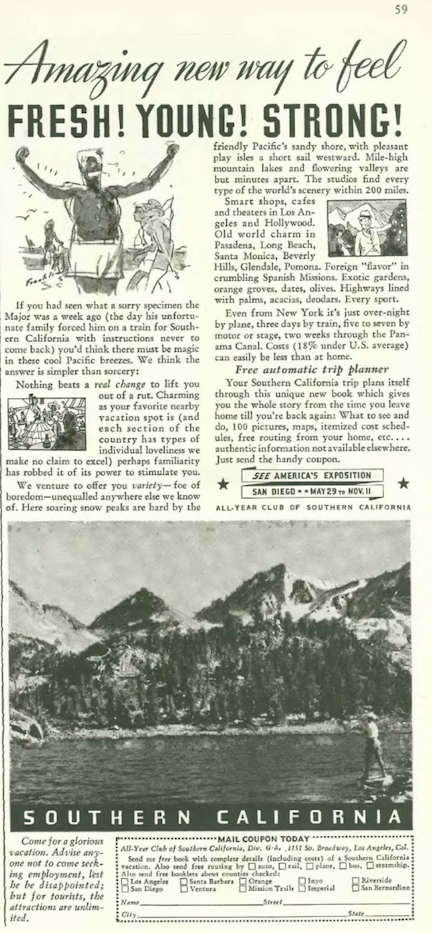

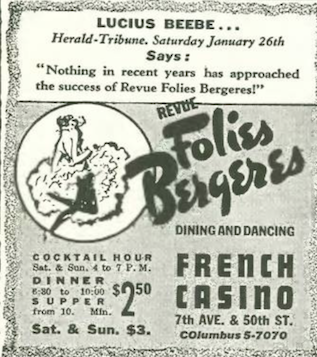

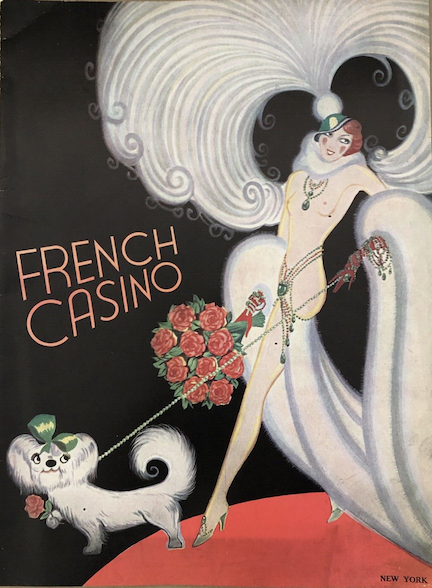

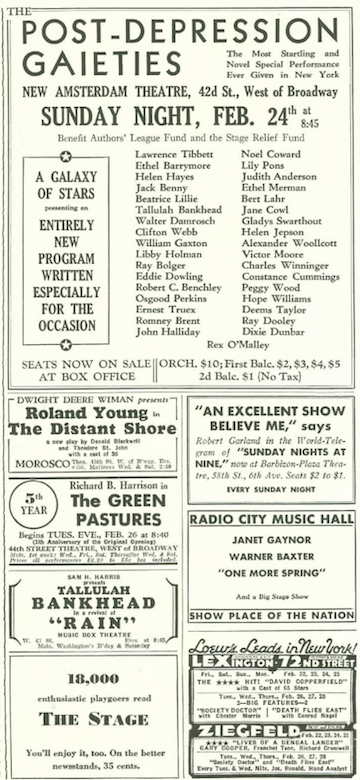

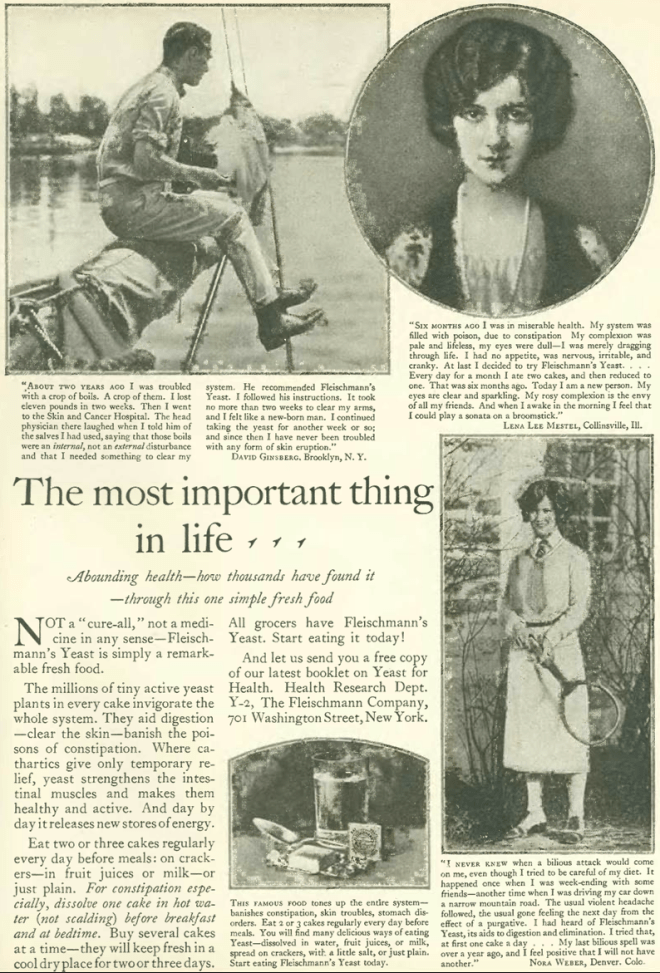

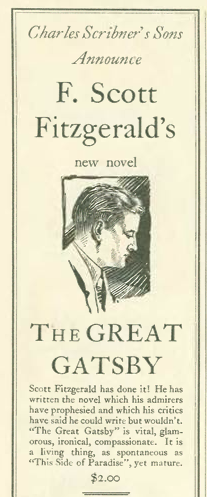

From Our Advertisers

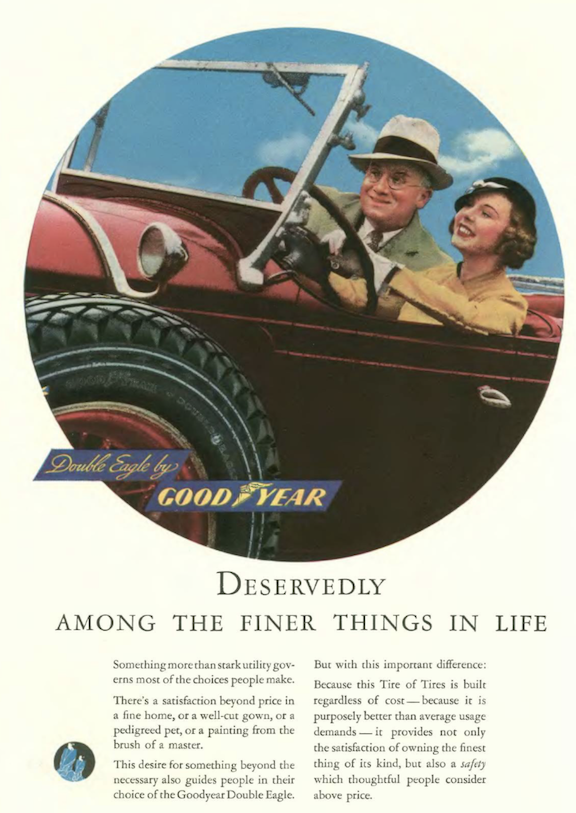

We begin with this advertisement from Goodyear, featuring what appears to be a father teaching his daughter how to drive, or in this case, fly, just like Chitty Chitty Bang Bang…

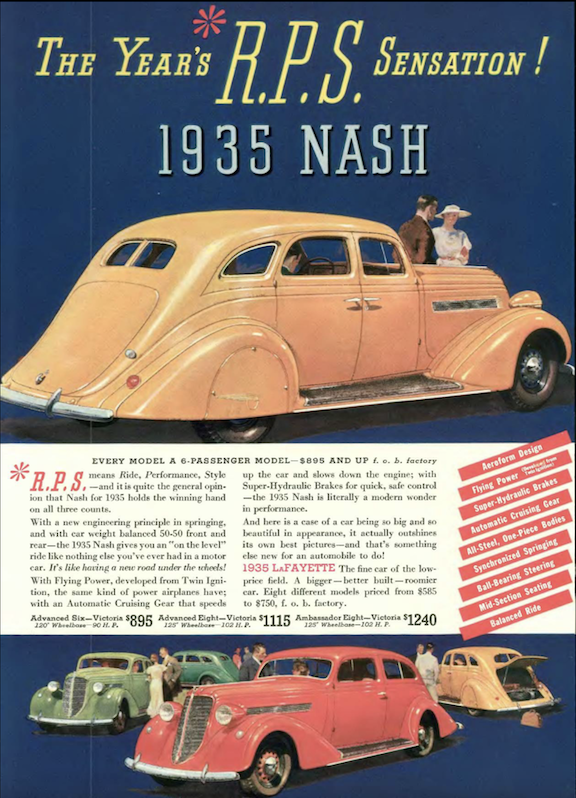

…and we stay airborne with the makers of the streamlined Nash, who claimed their automobile had “flying power”…

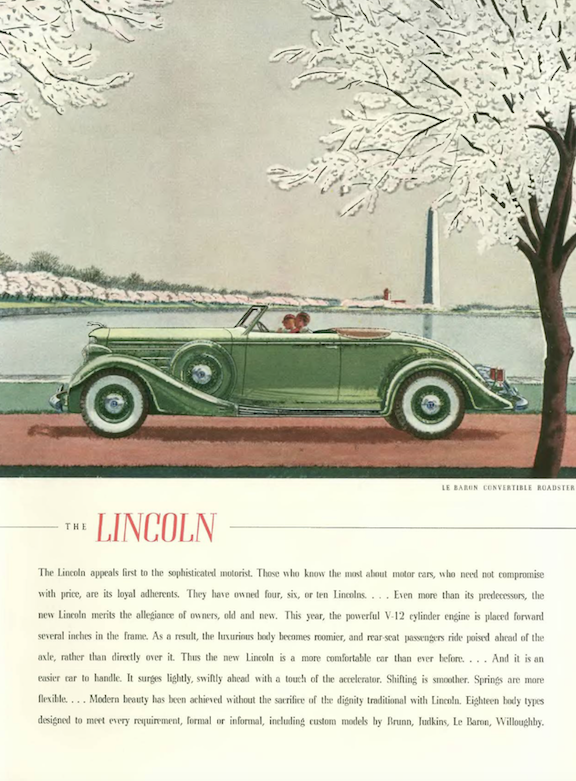

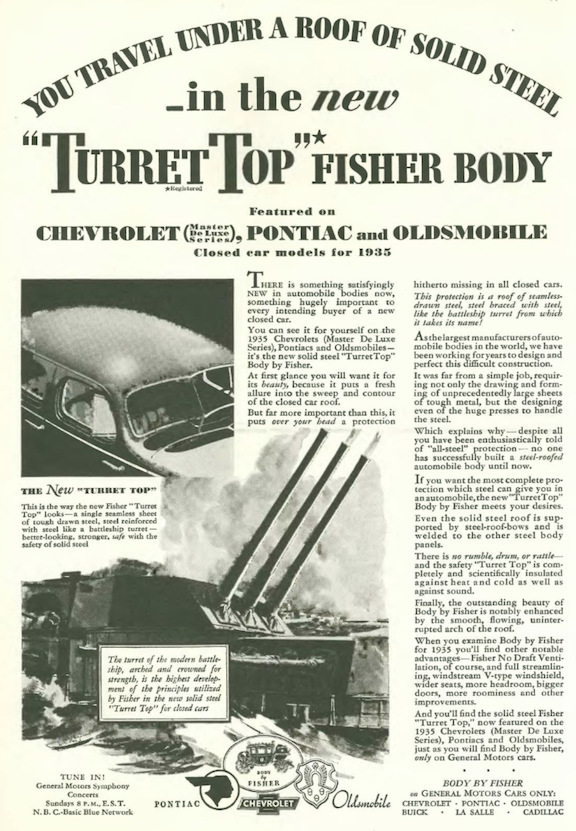

…and we return to earth with Cadillac’s budget model, the LaSalle, which featured “flashing performance”…

…by contrast, Pierce Arrow took a minimalist approach, gimmicks and splashy colors being reserved for the lower orders…

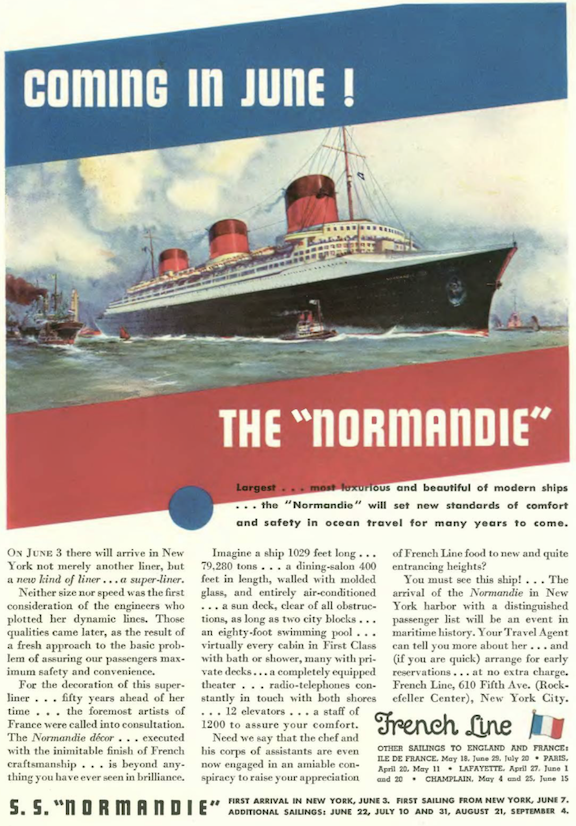

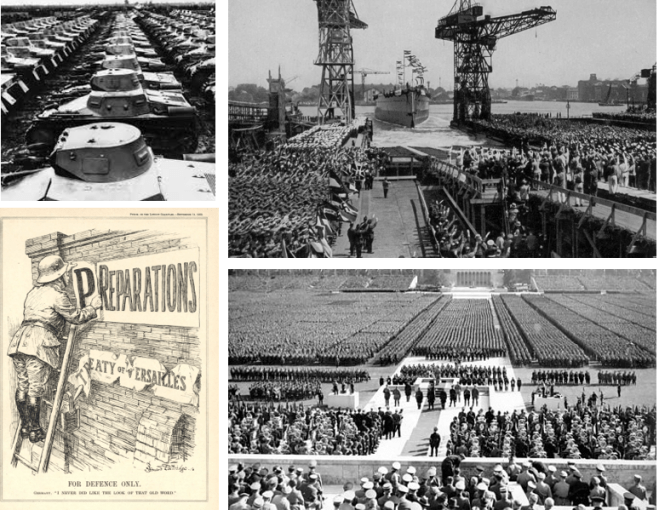

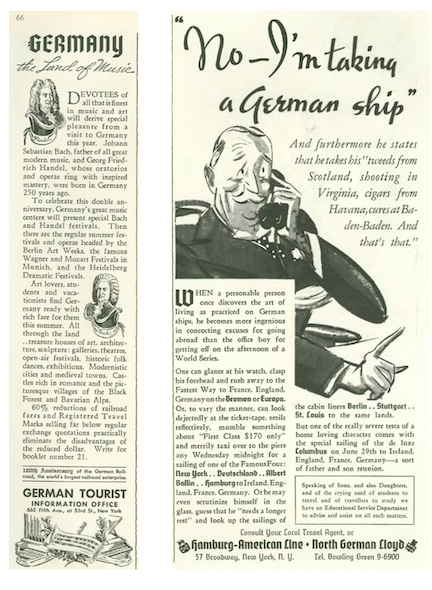

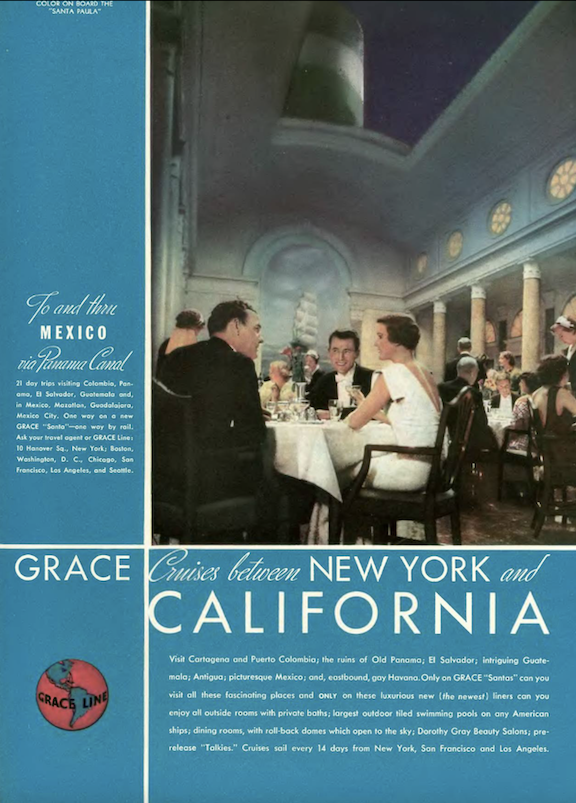

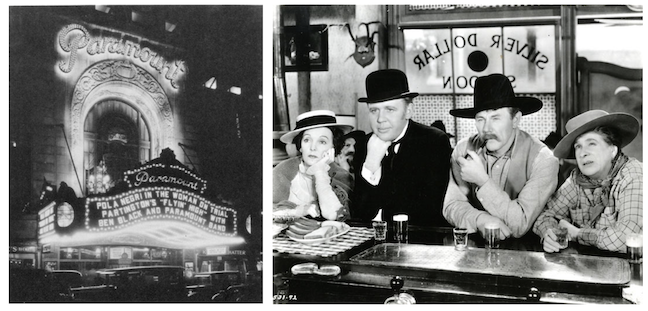

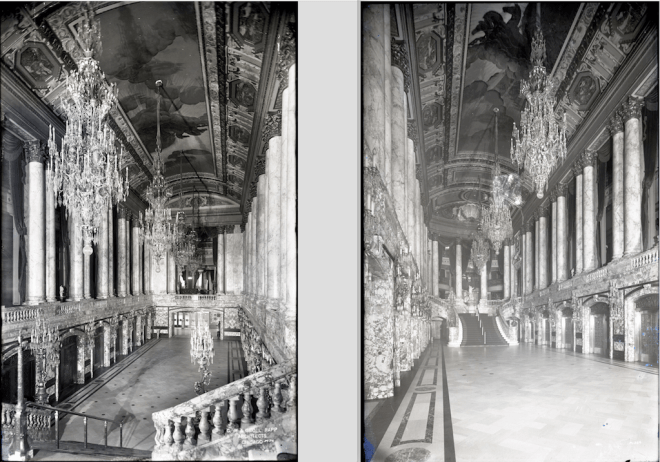

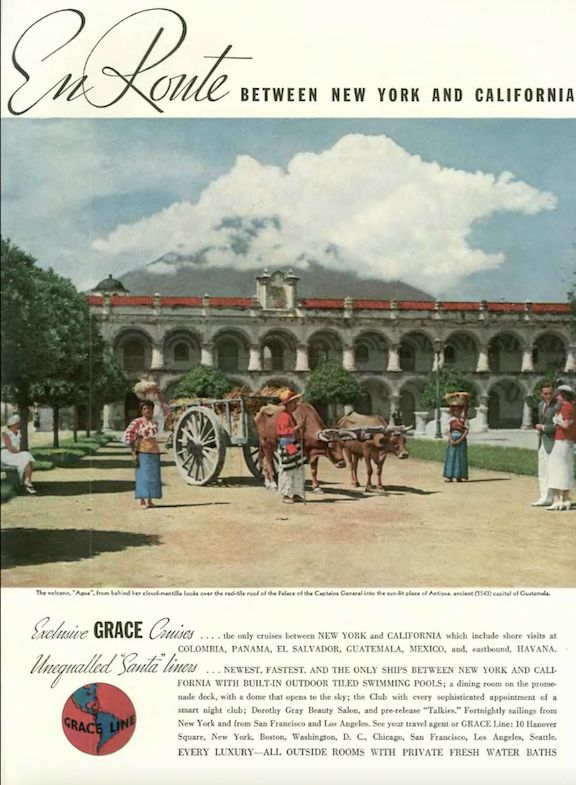

…one of the world’s most iconic ocean liners took to the sea with much fanfare in 1935. The SS Normandie was the largest and fastest passenger ship afloat; it remains the most powerful steam turbo-electric-propelled passenger ship ever built…

…if you happened to smoke Webster cigars, it could have been a sign that you were favored by the heavens…

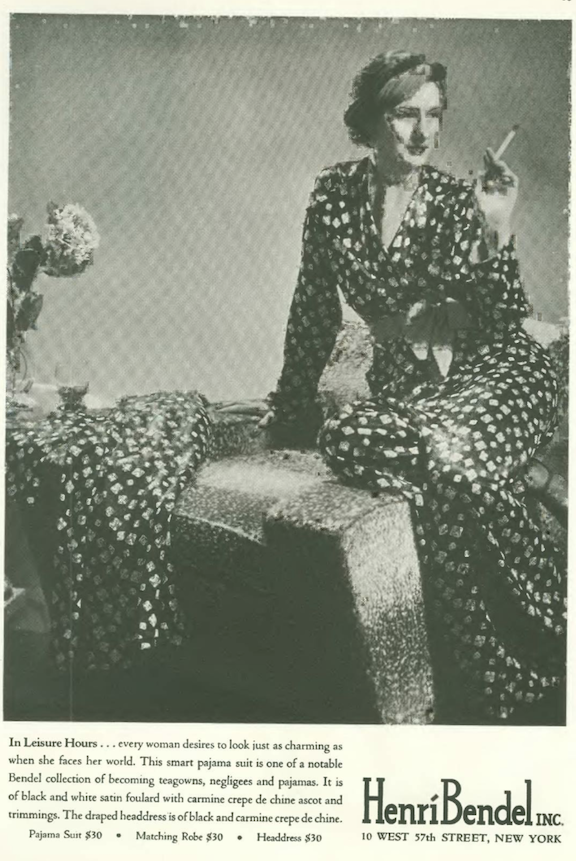

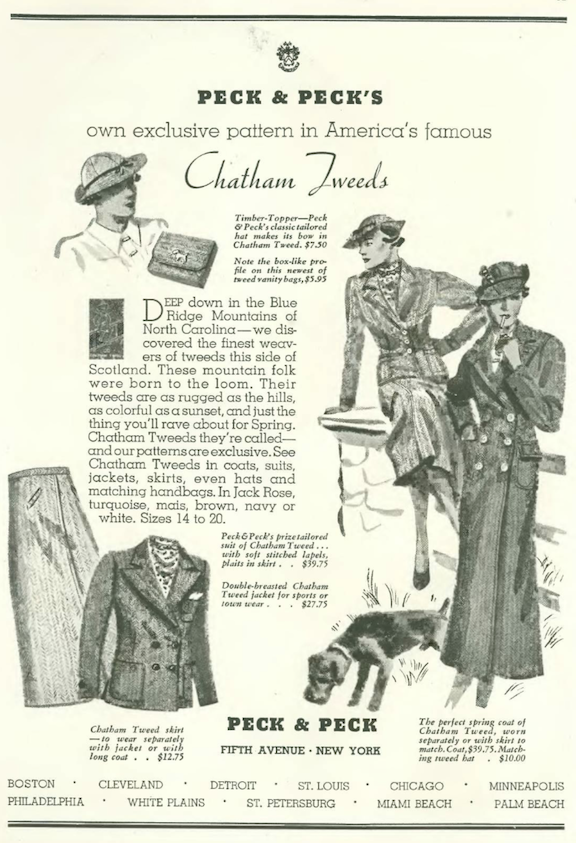

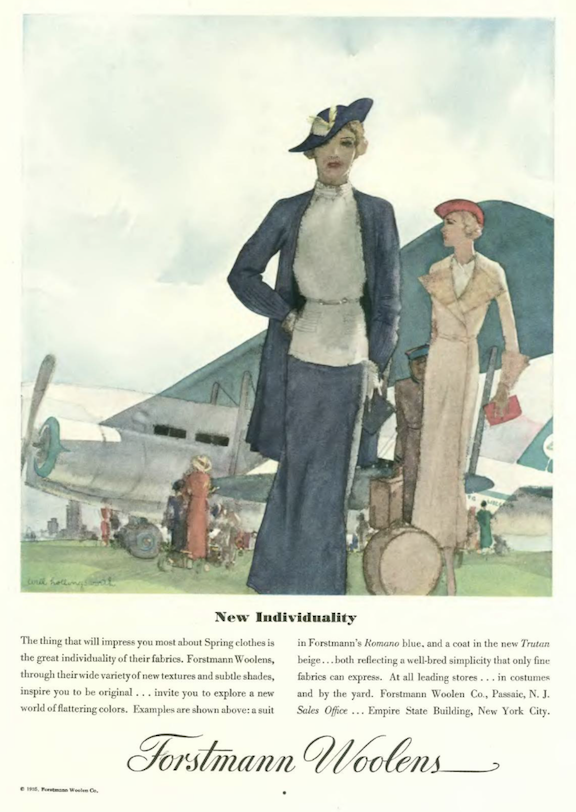

…the “20-year rule” in fashion suggests that trends have a tendency to re-emerge every two decades, and that seems to be the case here…

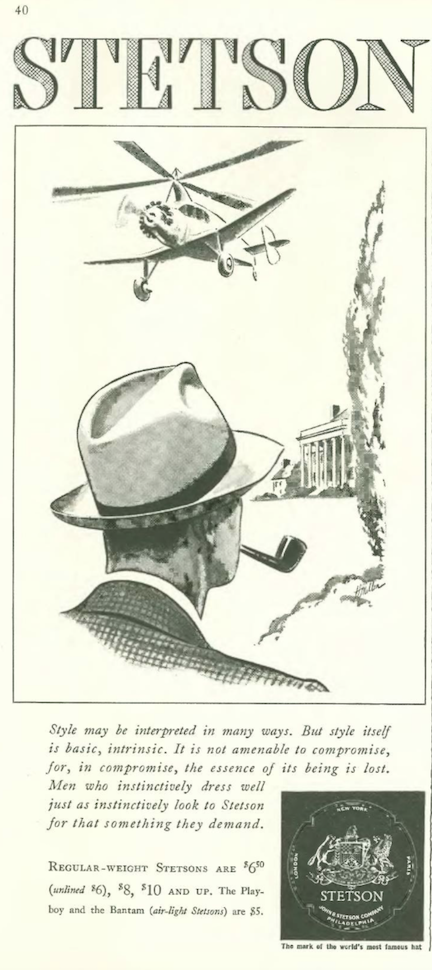

…this next ad tells us everything we need to know about the Stetson wearer: he is a wealthy country gentleman who values tradition but who is also a man of the future…from the 1920s to midcentury the autogyro was thought to be the answer to the long-dreamed of flying car…

…whoever coined the term “night cap” probably wasn’t thinking about cold cereal…

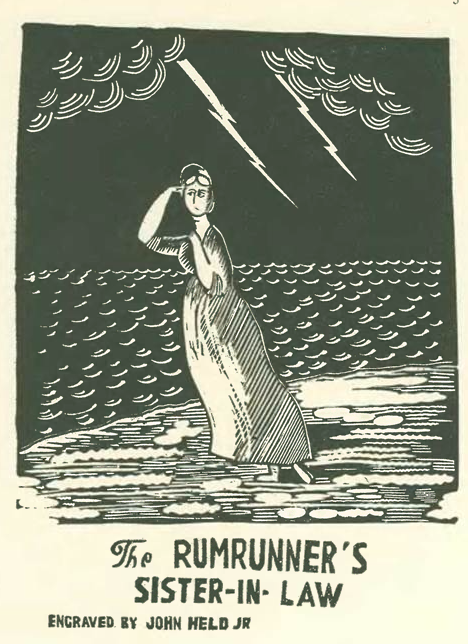

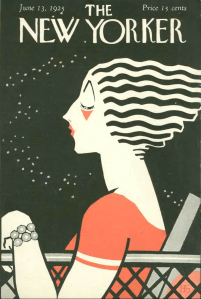

…although Harold Ross’s old high school friend, John Held Jr., contributed many woodcut-style cartoons and faux maps to The New Yorker from 1925 to 1932, Held was more famous for his shingle-bobbed flappers and their slick-haired boyfriends in puffy pants, a style more apparent in this ad for Peychaud’s Bitters (the original was a one-column ad, split here for clarity)…

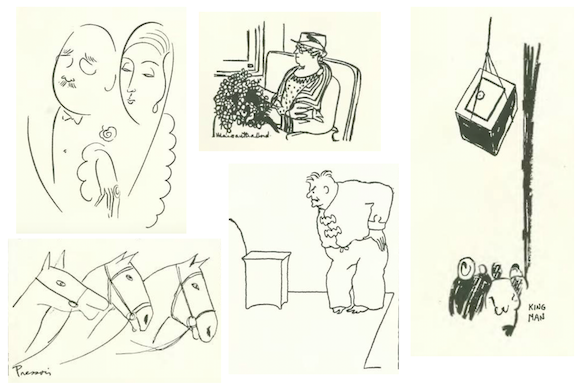

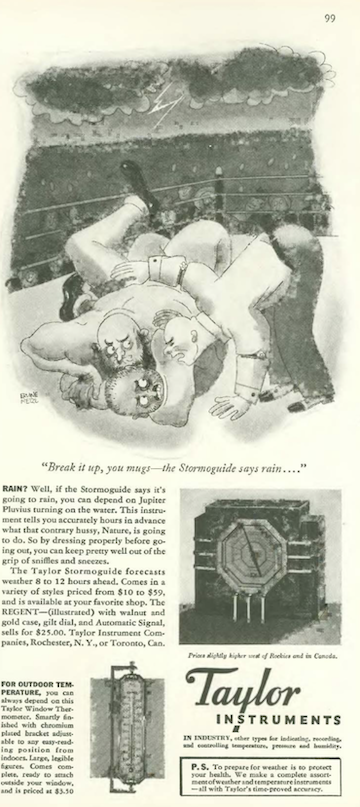

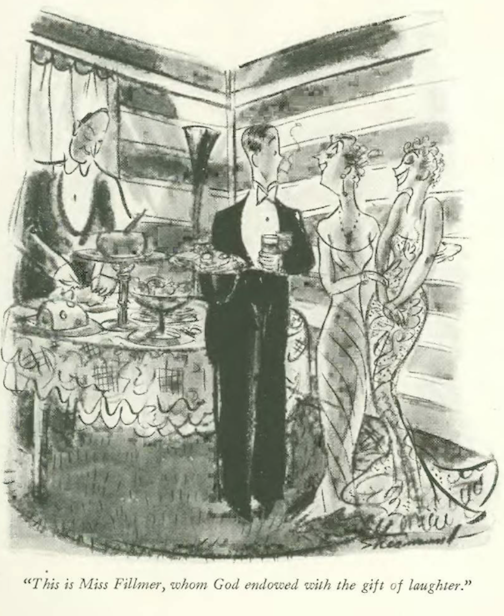

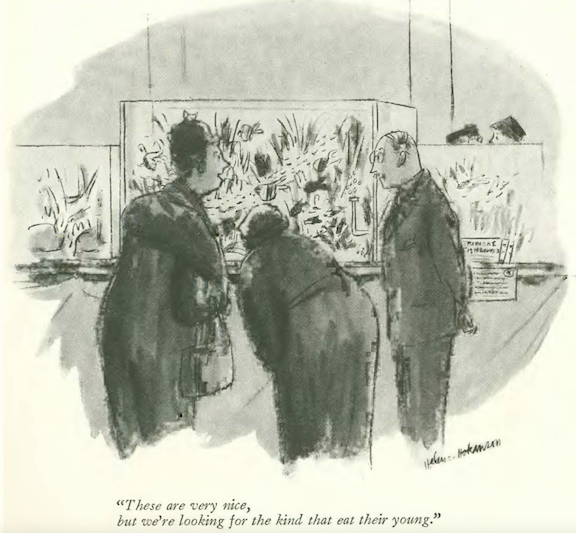

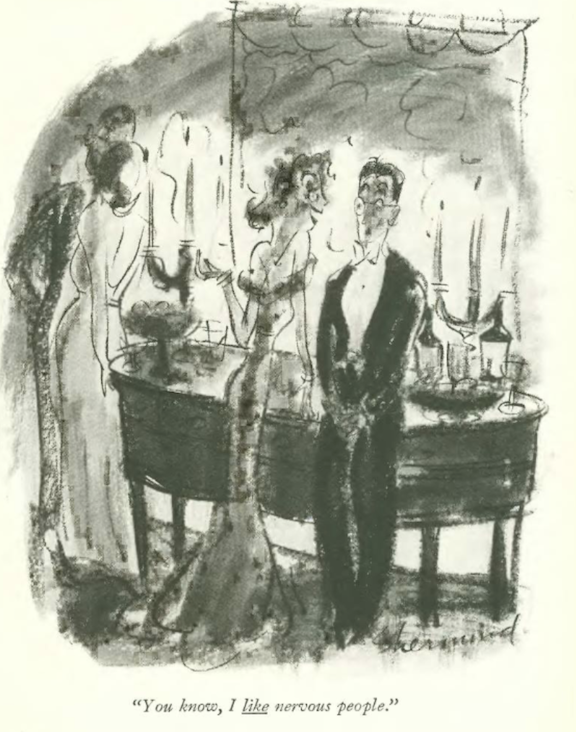

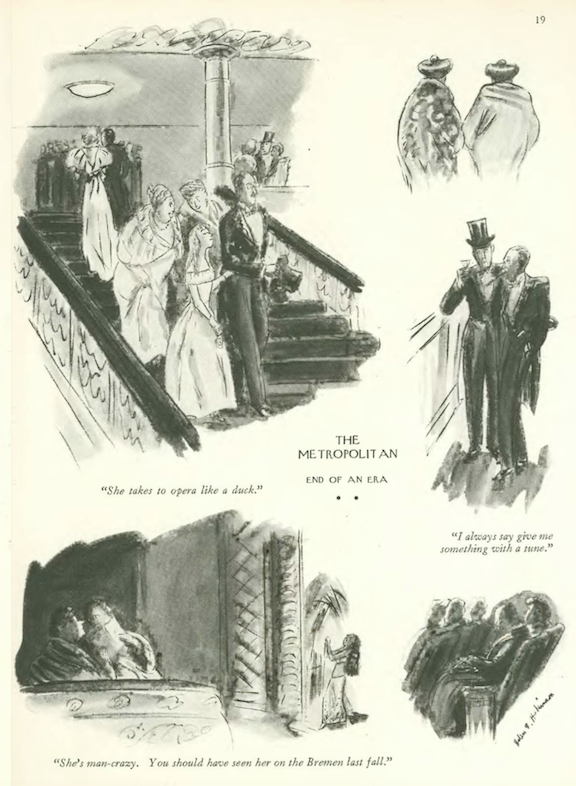

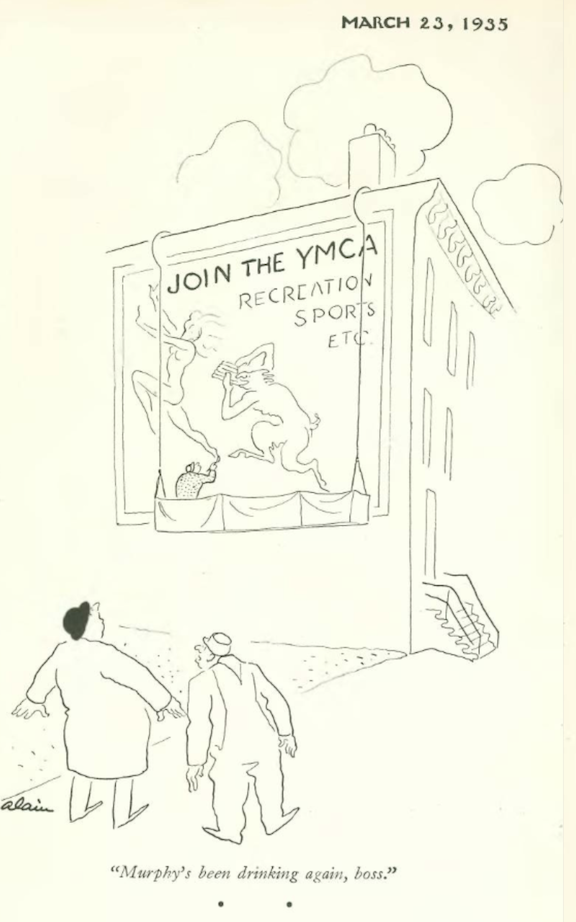

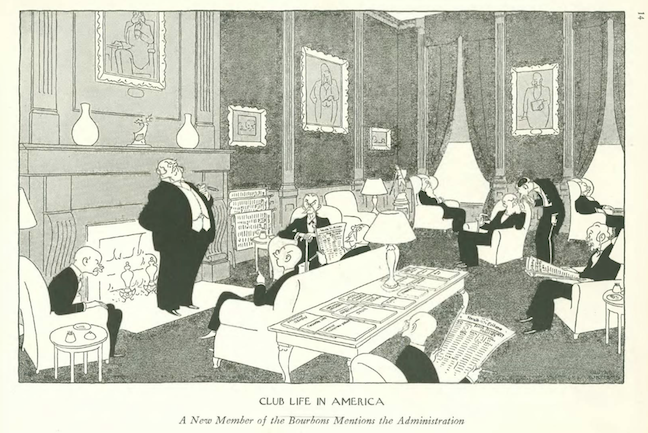

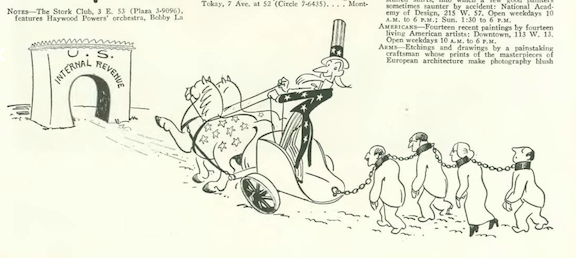

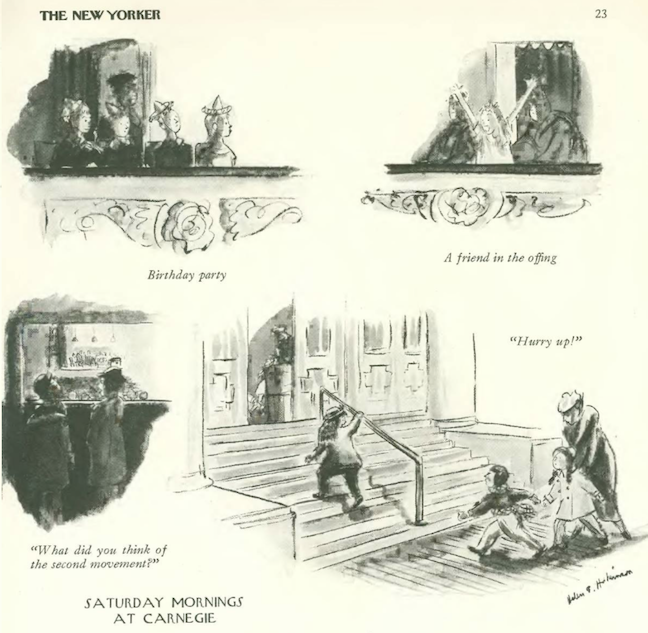

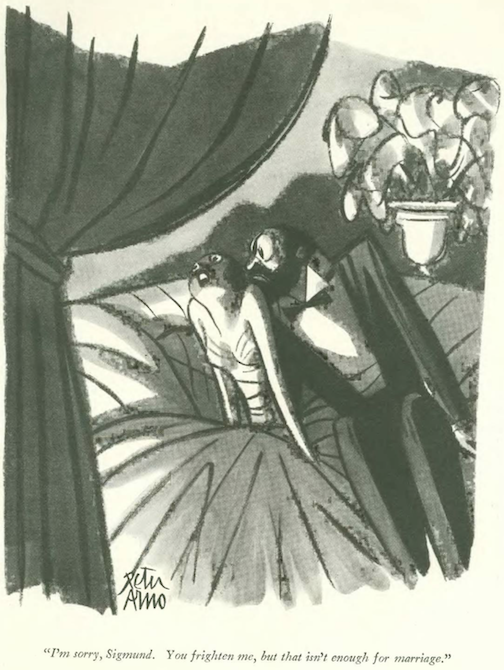

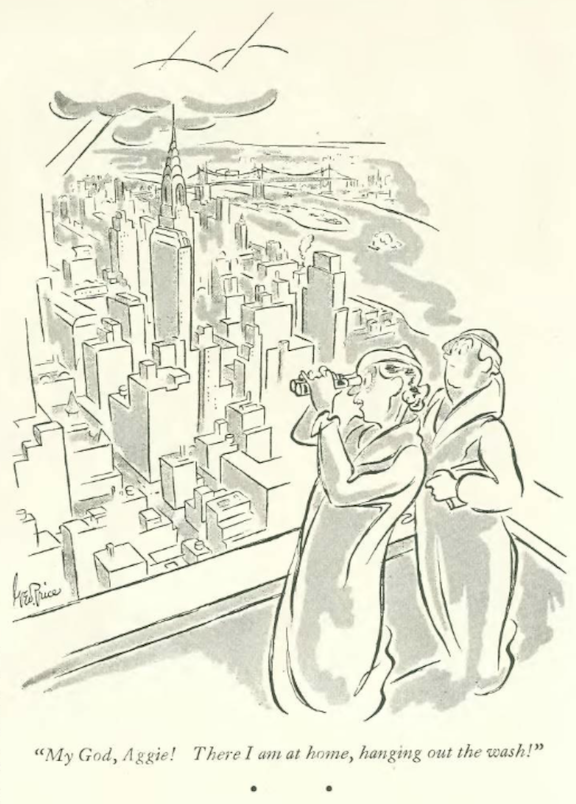

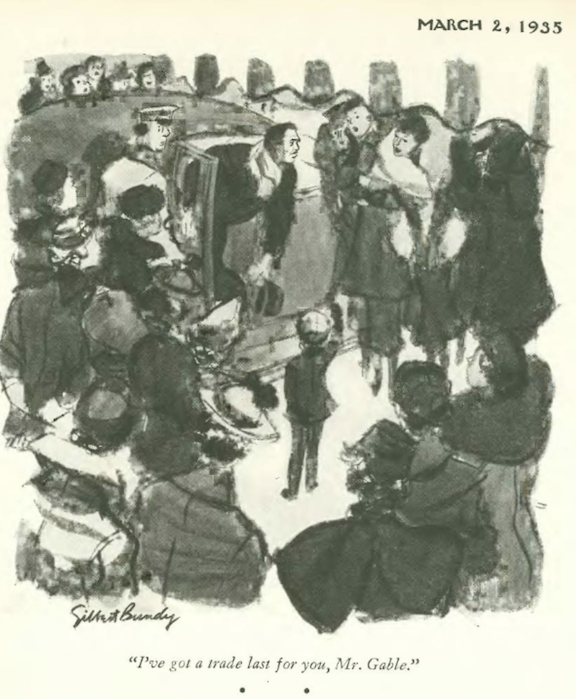

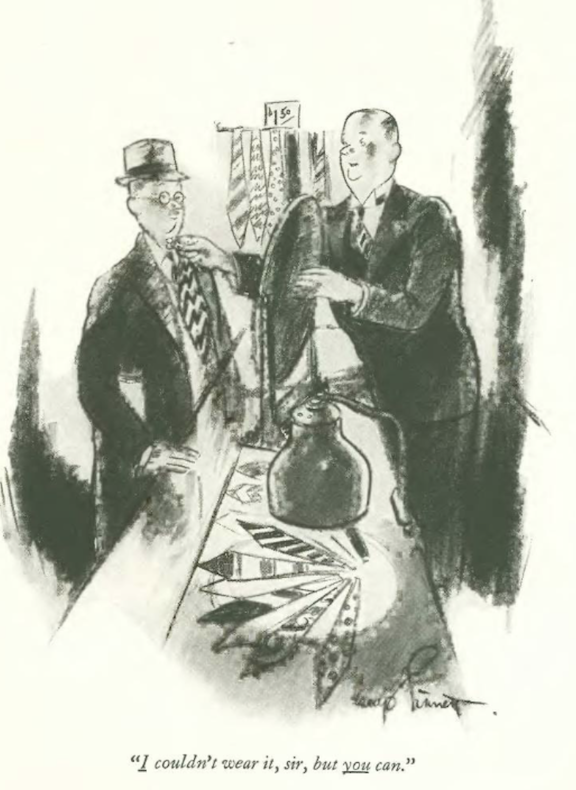

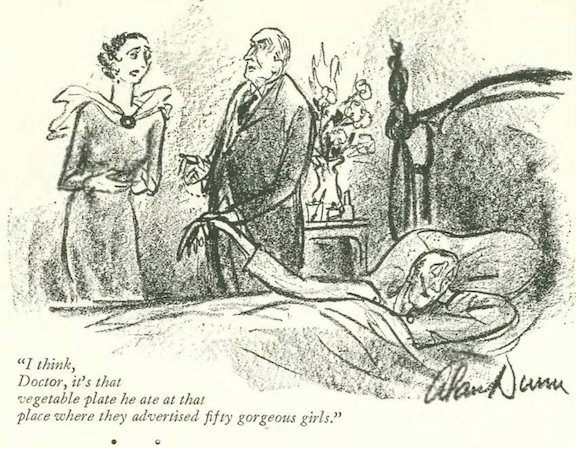

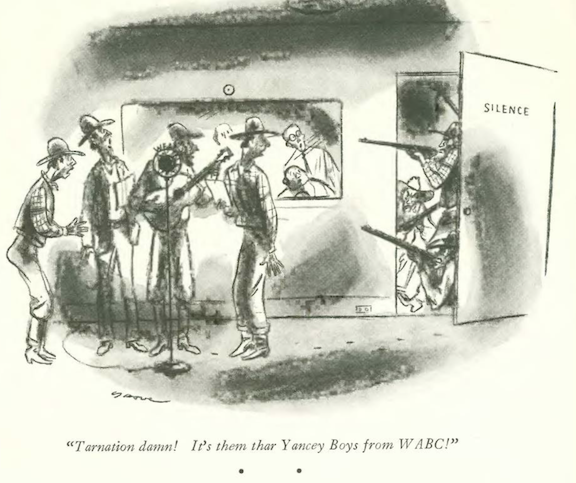

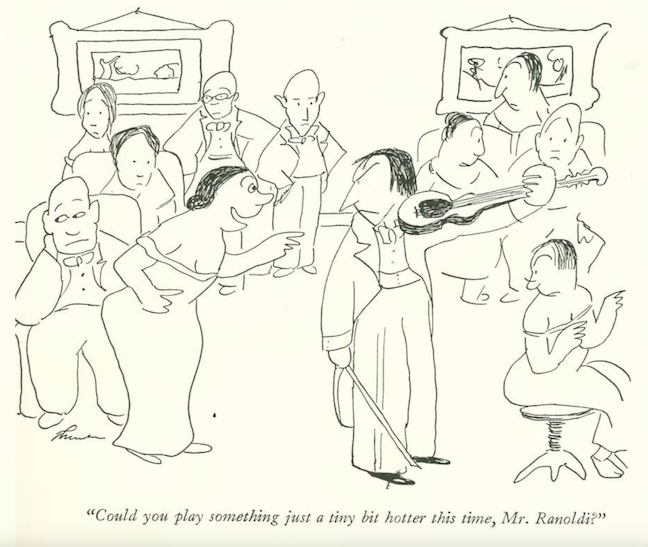

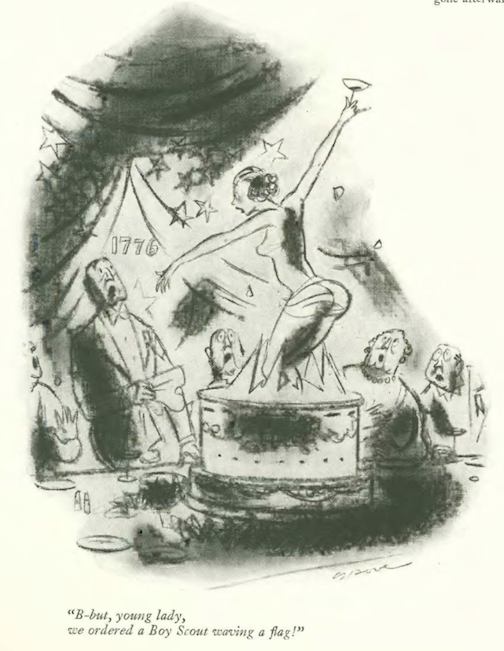

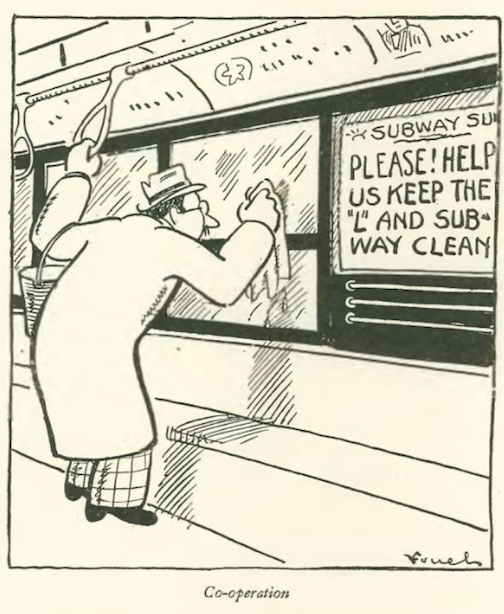

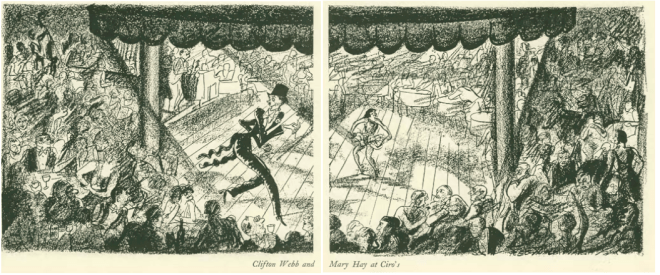

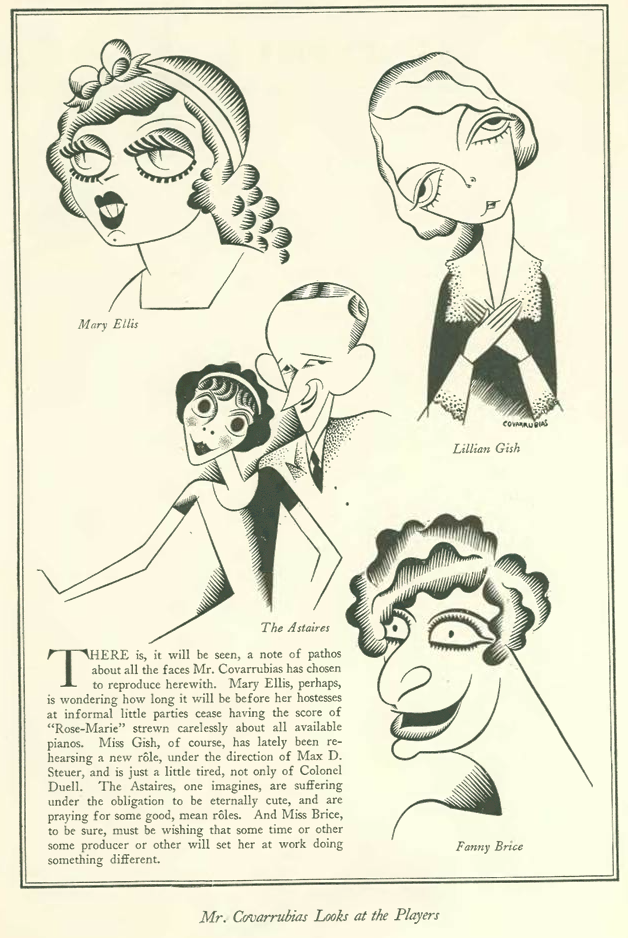

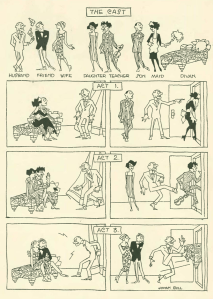

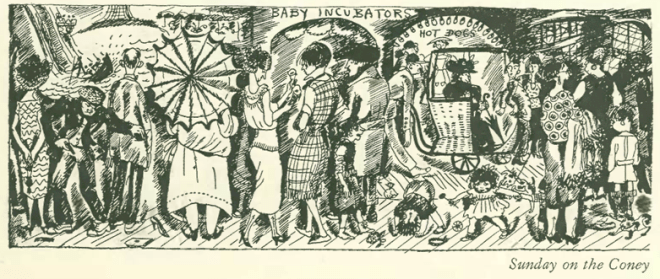

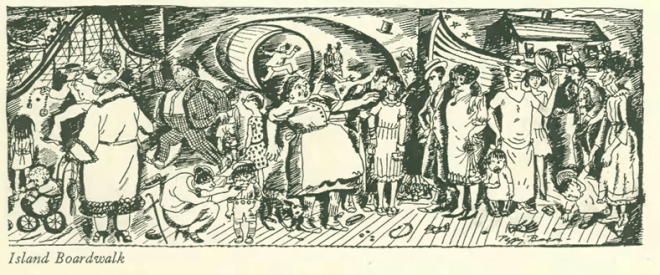

…Held provides a segue to our illustrators and cartoonists, beginning with a sampling of spot art from the April 13 issue…

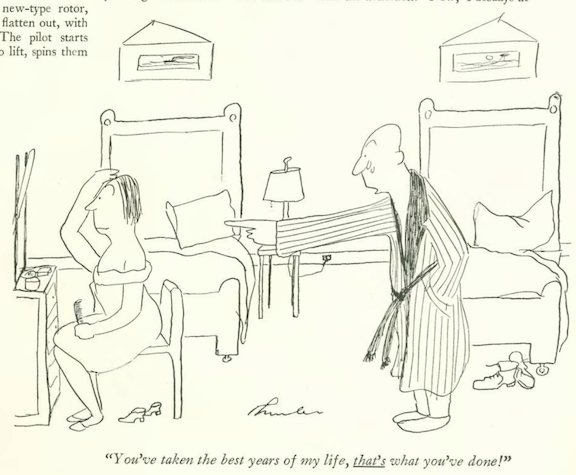

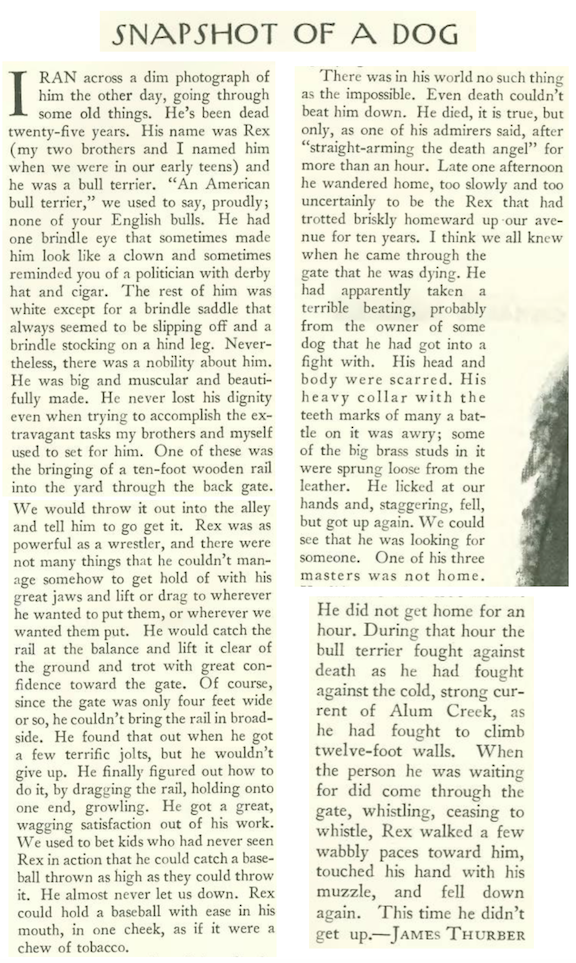

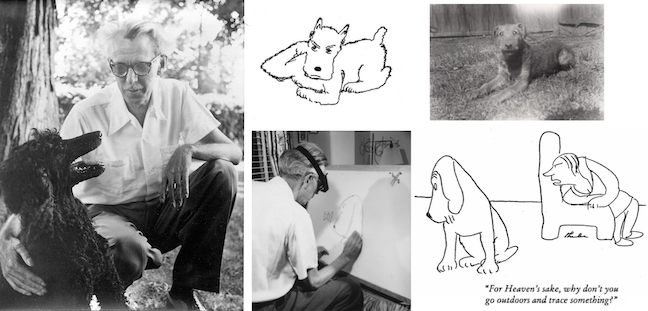

…James Thurber got things going on page 2…

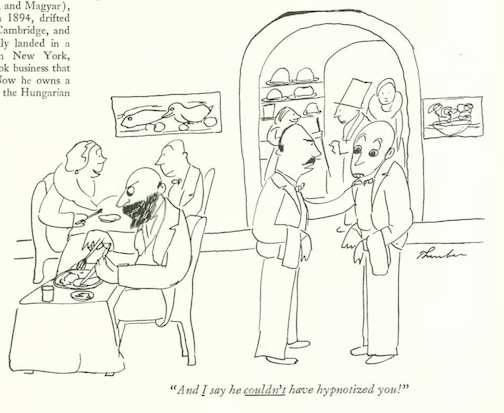

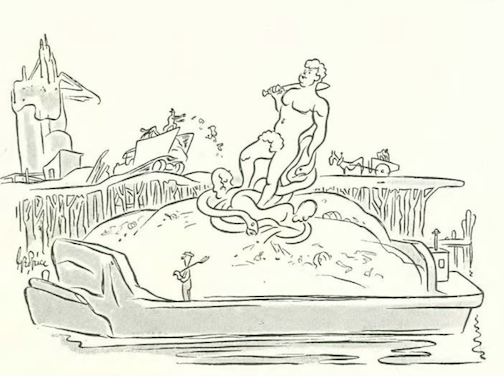

…and also contributed this observation of the hypnotic arts…

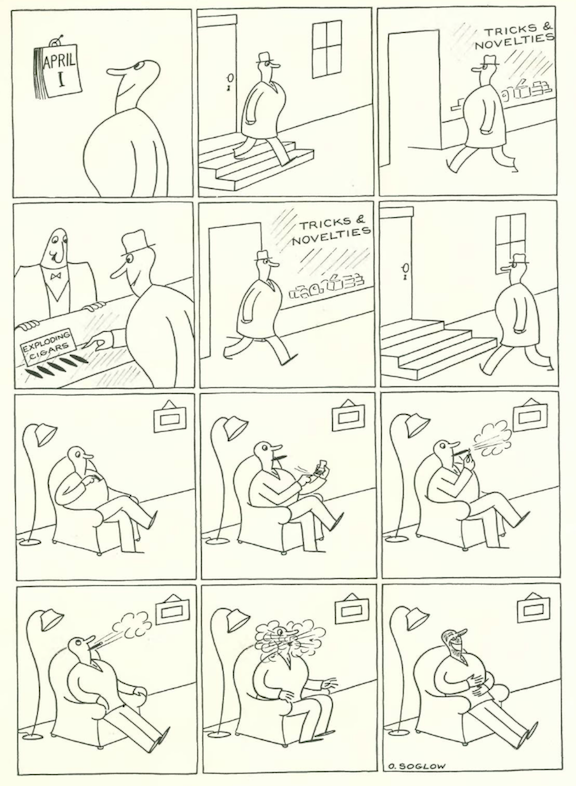

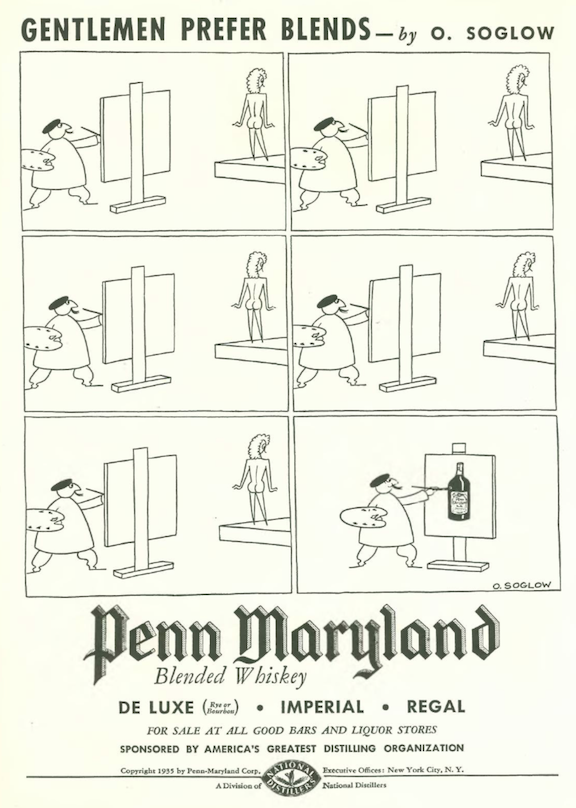

…Otto Soglow did some careful surveying (this originally appeared across two pages)…

…Alain looked in on some Vatican gossip…

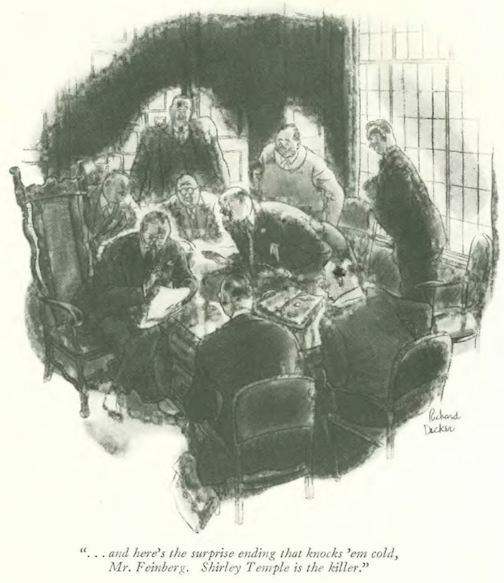

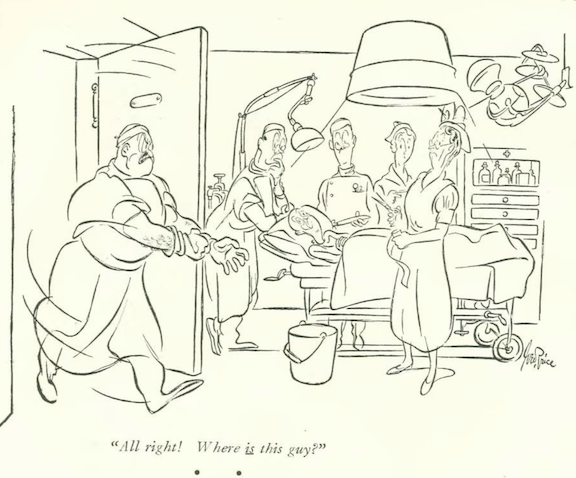

…Richard Decker pitched a Shirley Temple murder caper…

…Carl Rose gave us a sweet send-off…

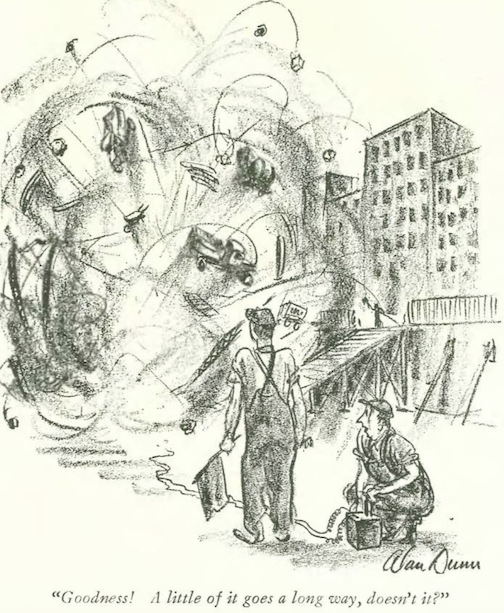

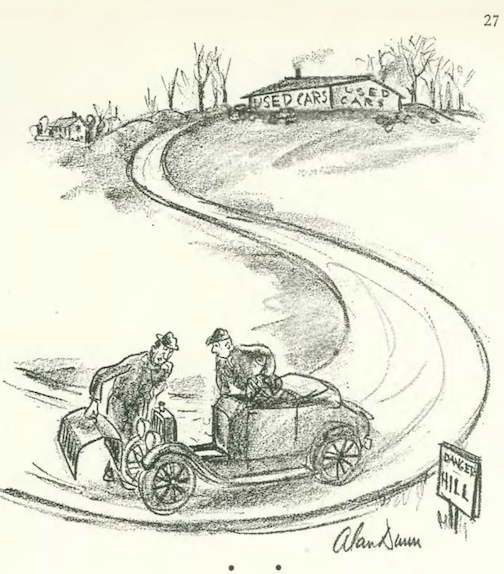

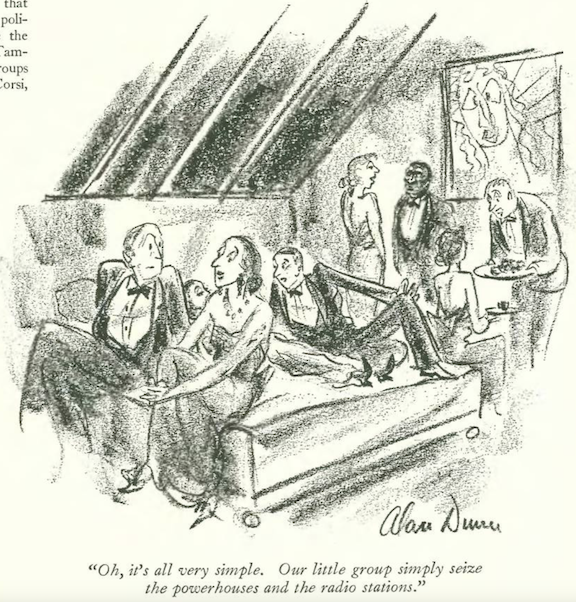

…and we close out with a big bang, courtesy of Alan Dunn…

Next Time: Terse Verse…