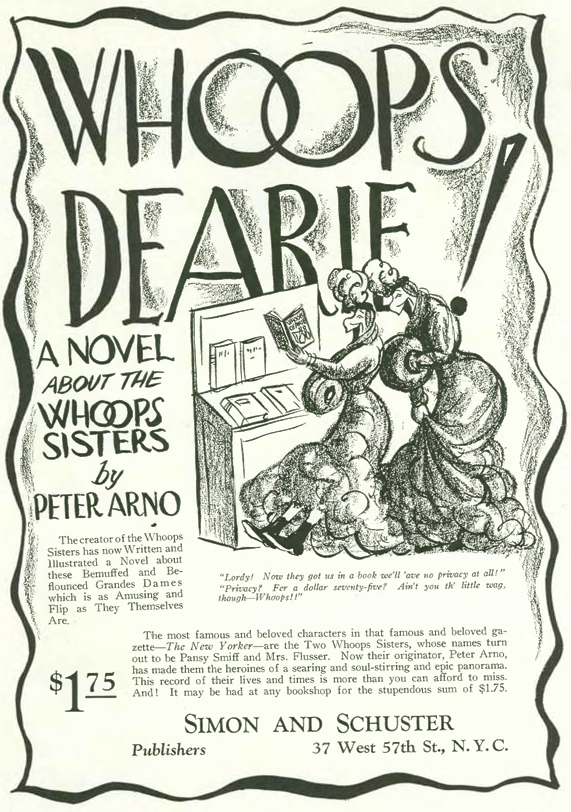

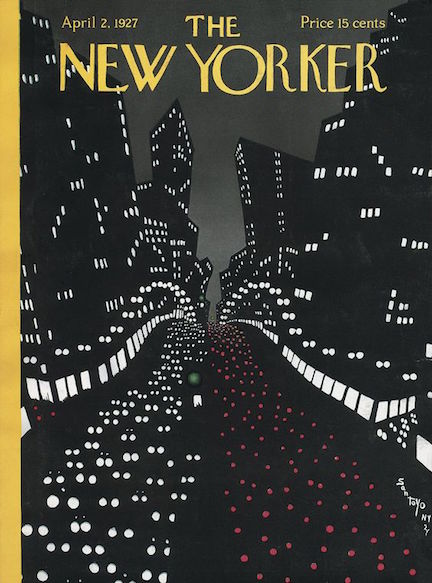

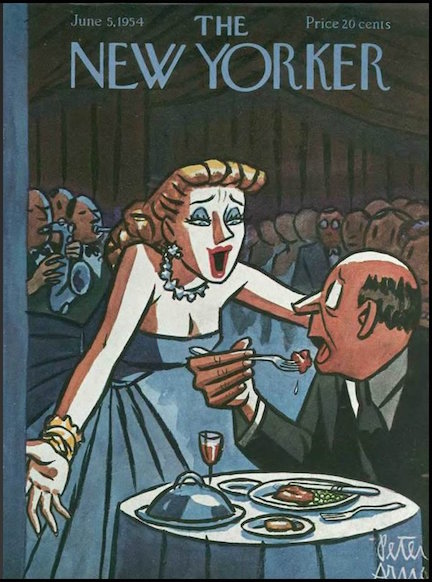

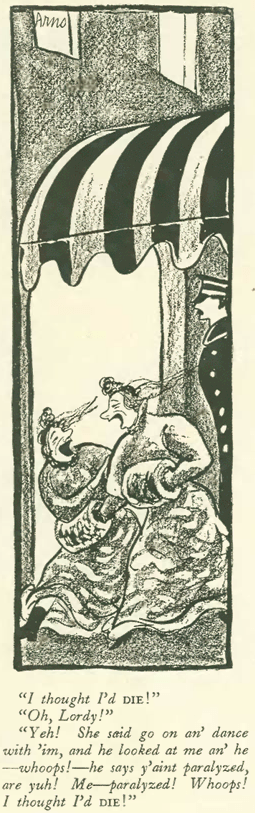

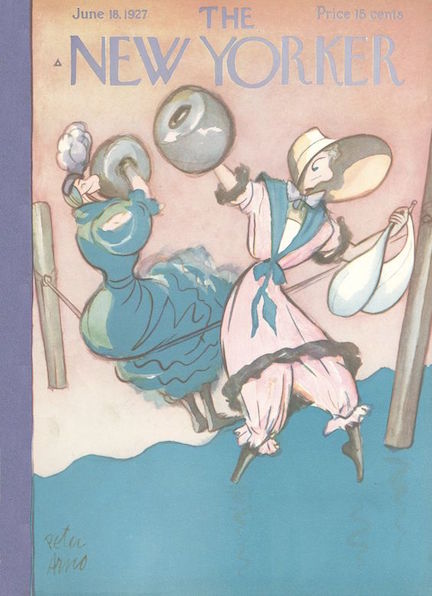

The New Yorker welcomed spring with a cover featuring Peter Arno’s popular Whoops Sisters testing the waters at the beach…

…and so was The New Yorker, on the south shores of Brooklyn to check out attractions old and new at Coney Island, paying a visit on an “off-day” to check out attractions ranging from incubating babies to the mechanical horse-race at the old Steeplechase:

Of course not everything was as dazzling as Luna Park at night. Like any carnival, Coney Island had its share of barkers announcing everything from games of “chance” to freak shows and a wax museum that depicted–among other grisly sights–the murder of Albert Snyder by his wife, Ruth Snyder, and her lover, Judd Gray, and the subsequent execution of the notorious pair.

Charles Lindbergh, feted with his own wax image at Coney Island, was beginning to appear on the verge of a meltdown thanks to the relentless attention he was getting in the aftermath of his historic flight:

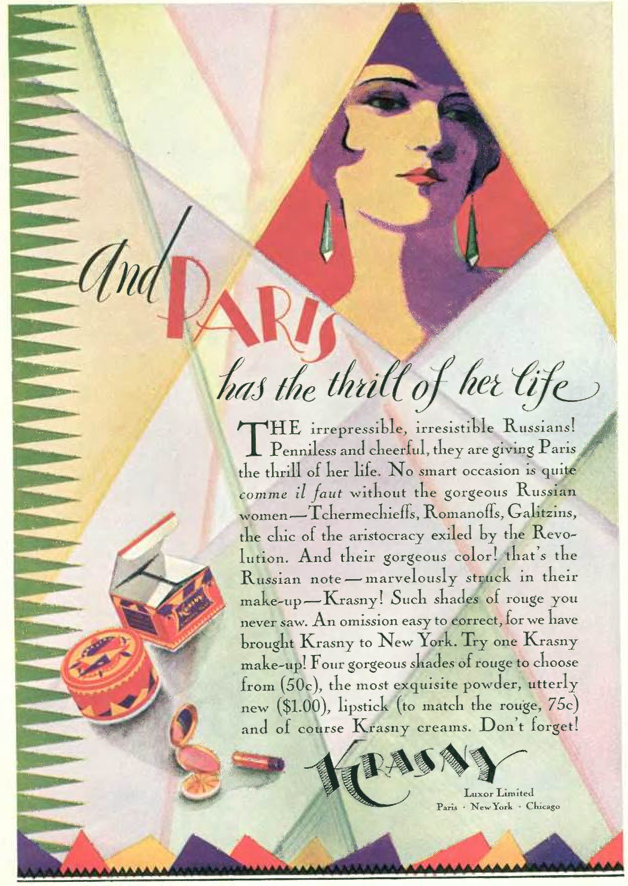

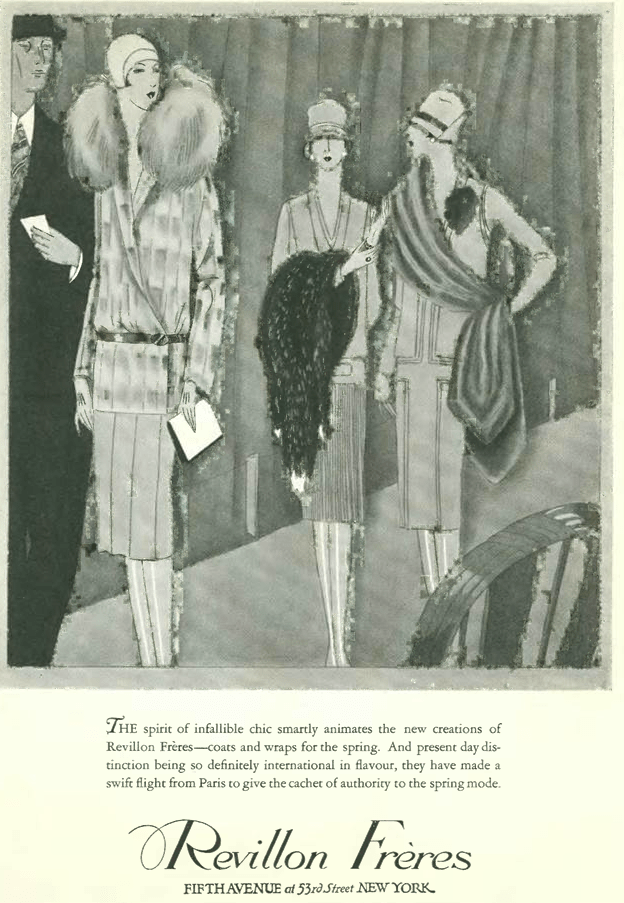

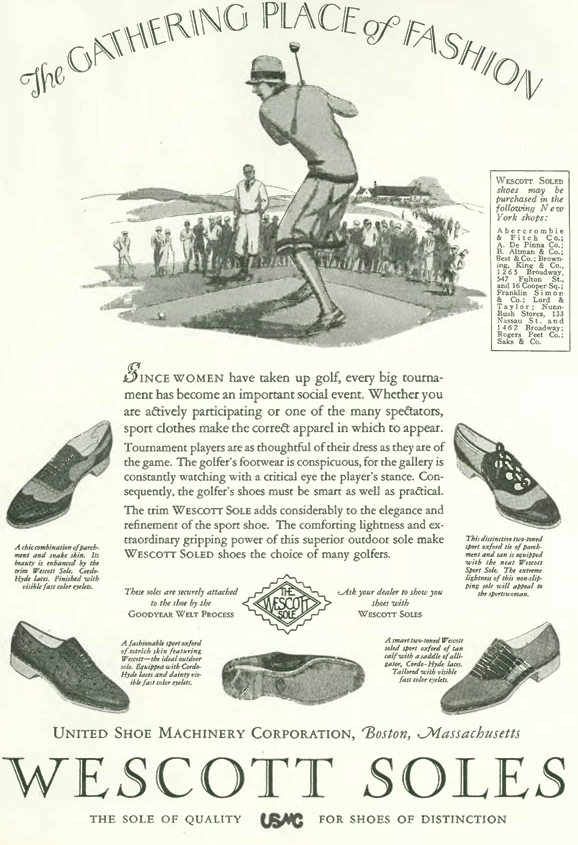

Lois Long also seemed at her wit’s end, abruptly announcing to readers that her nightlife column, “Tables for Two,” would go on hiatus for the summer. No doubt this was a relief to Long, who seemed to be growing weary of the nightclub scene and was doing double duty as fashion writer (“On and Off the Avenue”) for The New Yorker:

And perhaps there was another reason Long was taking a break–she would marry fellow New Yorker contributor and cartoonist Peter Arno on Aug. 13, 1927.

* * *

Always poised to take a poke at the newspaper media, The New Yorker had some fun with the New York Times’ attempt to reproduce an early wirephoto of Clarence Chamberlin, the second man to pilot a fixed-wing aircraft across the Atlantic from New York to Europe, while carrying the first transatlantic passenger, Charles Levine. The original photo apparently showed Chamberlain and Levine being greeted by the mayor of Kottbus, Germany:

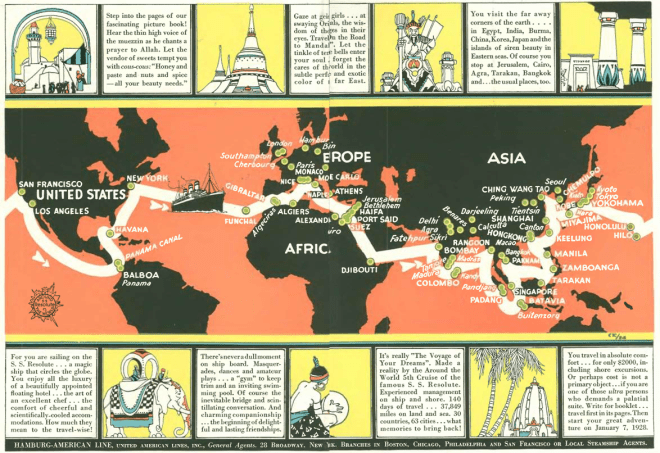

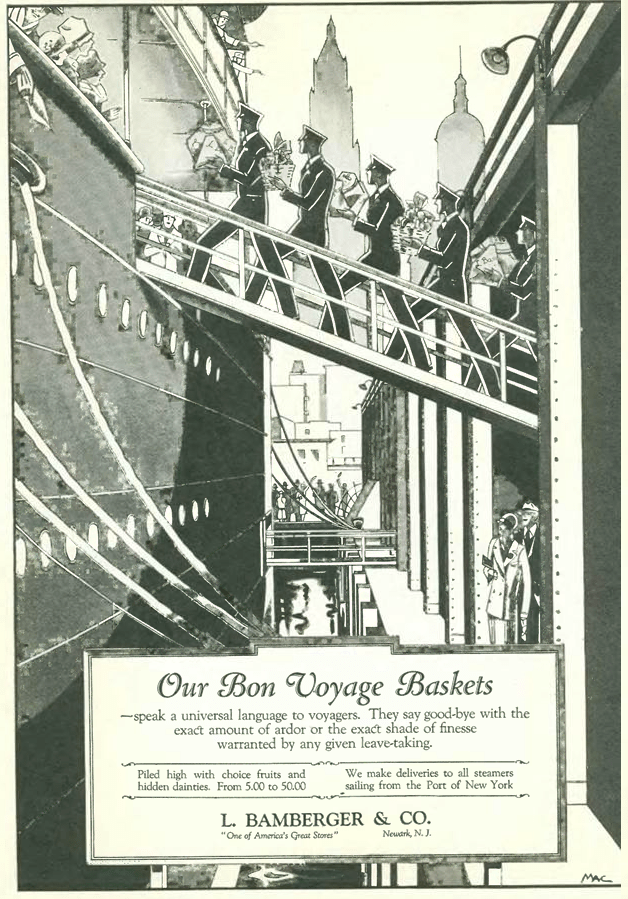

Charles Levine took a plane to Europe, but most still had to settle for the more leisurely pace of a steamship. Below is a two-page advertisement featured in the center of the June 18 issue for an around the world excursion on the Hamburg-American Line (click to enlarge):

And finally, this advertisement in the back pages for Old Gold cigarettes, which claimed to be “coughless”….

The artist for these Old Gold ads was Clare Briggs, an early American comic strip artist who rose to fame in 1904 with his strip A. Piker Clerk. Growing up in Lincoln, Nebraska gave Briggs the material he needed to depict Midwestern Americana, a style that would influence later cartoonists such as Frank King (Gasoline Alley).

Next Time: Île-de-France…