Above: A scene from Mary Pickford’s 1922 film Tess of the Storm Country. (Library of Congress)

In today’s celebrity-saturated culture it is difficult to find a parallel to silent film star Mary Pickford, who was dubbed Queen of the Movies more than a century ago. Indeed, during the 1910s and 1920s Pickford was regarded as the most famous woman in the world.

Pickford was also known as “America’s Sweet” for her portrayal of gutsy but tenderhearted heroines. In real life she was also a gutsy and shrewd businesswoman who co-founded United Artists in 1919 with Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and director D. W. Griffith. Commanding a salary only rivaled by Chaplin, her stardom only grew when she married Fairbanks in 1920, forming the first celebrity supercouple; together they ruled Hollywood from their Beverly Hills mansion, Pickfair (apparently staging dull affairs, per the “Profile” excerpt below).

The end of the silent era also put an end to Pickford’s stardom, as well as to her fairytale marriage to Fairbanks. Margaret Case Harriman’s profile of Pickford, simply titled “Sweetheart,” gave readers a glimpse into the decline of a silent superstar. Excerpts:

Harriman concluded her profile with some thoughts on Pickford’s future:

A note on the profile’s writer, Margaret Case Harriman (1904-1966), who doubtless sharpened her people-watching skills at the Hotel Algonquin (famed birthing ground of the New Yorker), which was owned by her father, Frank Case. Douglas Fairbanks was one of Case’s best friends, and Harriman knew both Fairbanks and Pickford well, since they often stayed at the hotel.

* * *

Master of Masters

The founder of perhaps the world’s most prestigious golf tournament was an amateur and a working lawyer by profession. When Bobby Jones (1902–1971) co-founded the Masters Tournament in 1934 with investment dealer Clifford Robert, it was called the Augusta National Invitation Tournament (it was Robert’s idea to call it The Masters, a name Jones thought immodest). Jones dominated top-level amateur competition from the early 1920s through 1930—the year he achieved a Grand Slam by winning golf ’s four major tournaments in the same year. However, by the 1934 Jones’s skills began to wane. The New Yorker had little to say about the first Masters (it wasn’t a big deal yet), other than Howard Brubaker making this observation in “Of All Things”…

* * *

From Our Advertisers

Wanna get away? This colorful advertisement beckoned New Yorker readers to take the next boat to sunny Bermuda…

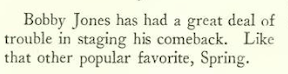

…while the Grace Line offered a southern cruise through the Panama Canal…

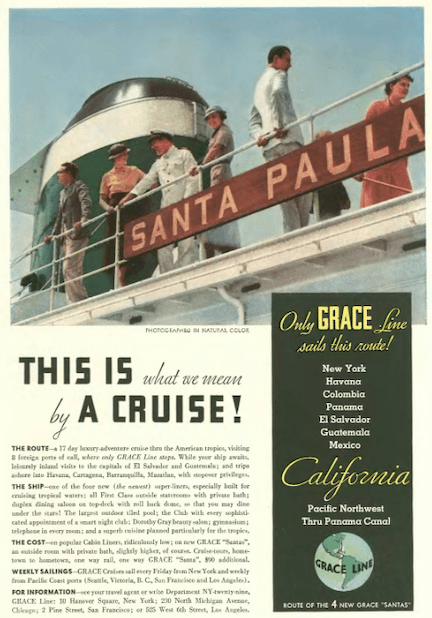

…but who needed to travel when you could enjoy a beer that was beloved the world over?…

…Mrs. Potter d’Orsay Palmer nee Maria Eugenia Martinez de Hoz was content to stay home in Chicago and smoke a few Camels, apparently…

…we’ve encountered her before—she appeared in a Ponds ad (below) in the Aug. 8, 1931 issue of the New Yorker, where we learned she was wife No. 2 of Potter d’Orsay Palmer, son of the wealthy family of Chicago Palmer House fame…they would divorce in 1937, and the playboy Potter would marry two more times before dying of a cerebral hemorrhage in May 1939—following a drunken brawl in Sarasota, Florida with a meat cutter called Kenneth Nosworthy. Maria Eugenia would remarry and return to her homeland of Argentina to raise a family…

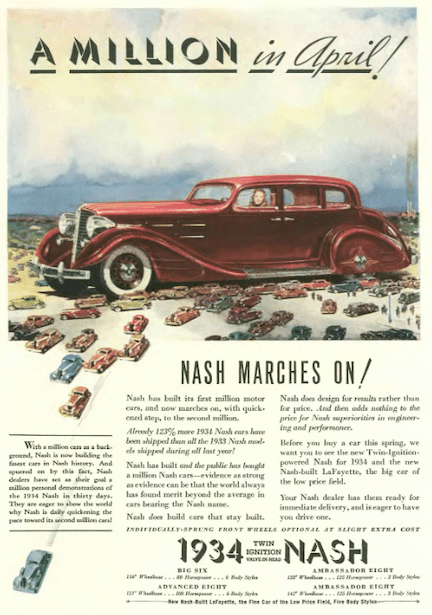

…this ad from Nash looks like a scene from Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, if she had a car to match, that is…

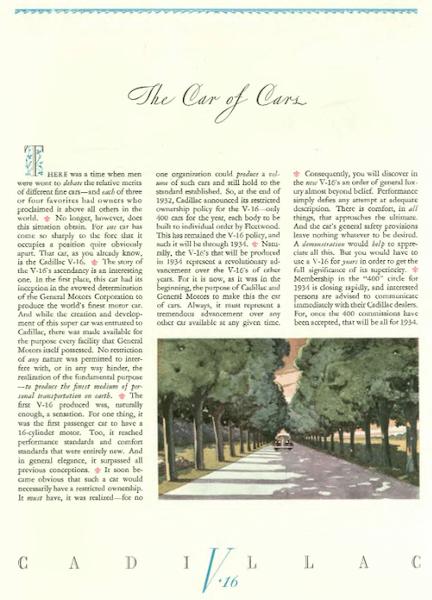

…the Cadillac V-16 was a truly massive automobile, but in contrast to the Nash ad, you can barely see the car as it approaches from the vanishing distance…

…E. Simms Campbell got in on the advertising game with this spot that features contrasting images of storm and calm…

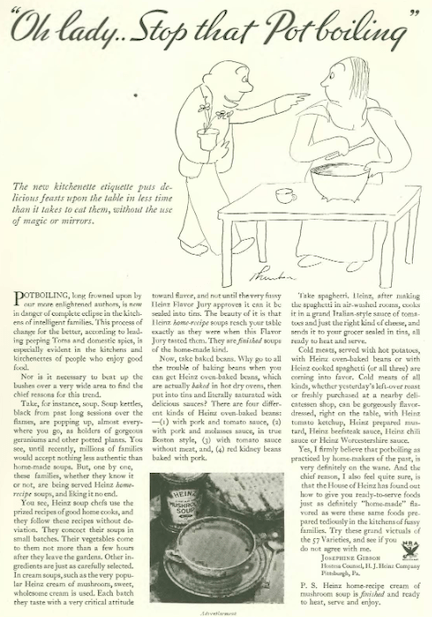

…James Thurber offered this cartoon on behalf of Heinz soups…

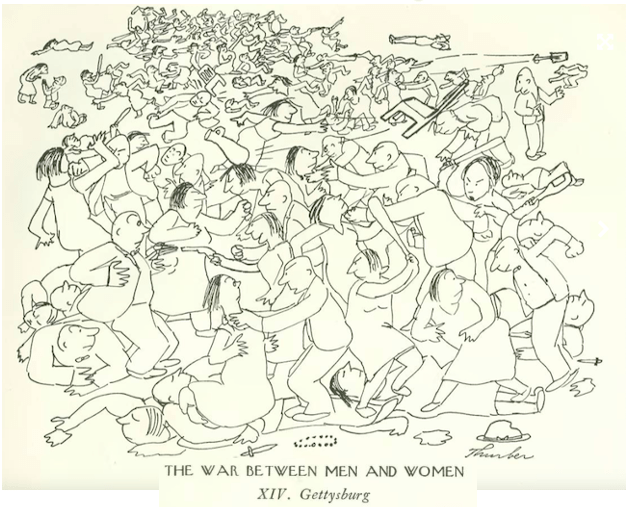

…and Thurber again, as we kick off the cartoons with the ongoing battle…

…Adolph Schus made a rare appearance in the New Yorker…according to Ink Spill, he also contributed a cartoon on March 19, 1938, and was editor of Pageant Magazine in 1945…

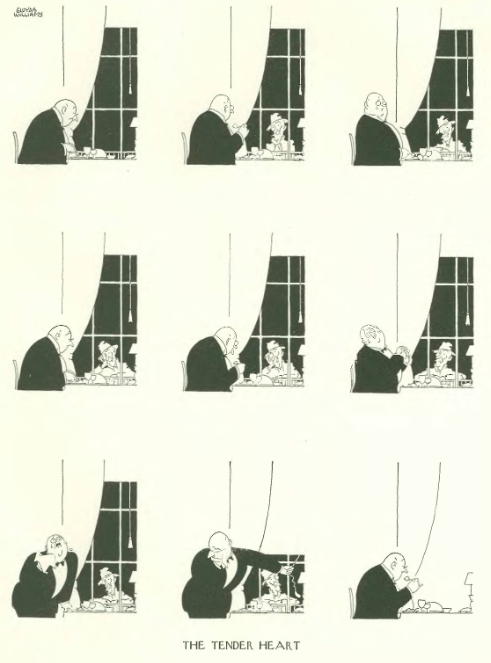

…Gluyas Williams looked in on the sorrows of moneyed classes…

…Helen Hokinson’s “girls” were in search of lunch, and propriety…

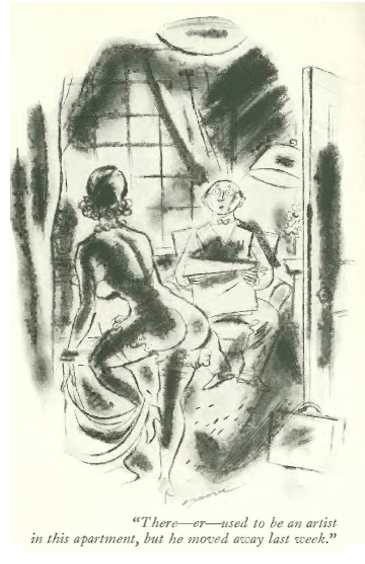

…and Leonard Dove gave us a renter surprised by something not included in his lease…

…on to April 14, 1934…

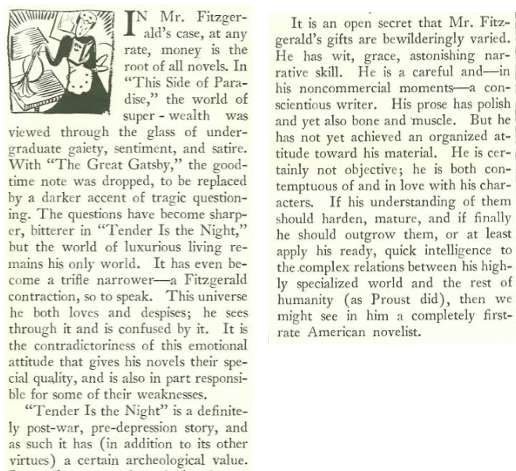

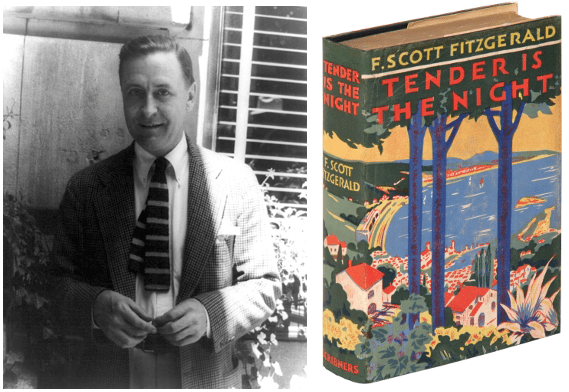

…and book reviewer Clifton Fadiman, who found F. Scott Fitzgerald’s literary gifts “bewilderingly varied”…

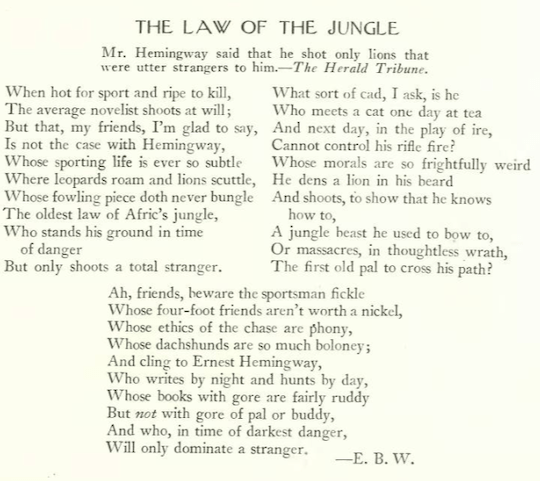

…speaking of F. Scott Fitzgerald, fellow author Ernest Hemingway defended Fitzgerald’s writing, arguing that criticism of his Jazz Age settings stemmed from superficial readings. One then wonders what Hemingway thought of E.B. White’s poetic “tribute” to his big game hunting excursions…

* * *

From History’s Ash Heap

Various reference sources cite “freak shows” as a normal part of American culture in the late 19th to the early 20th centuries, but I have to admit I saw exhibits at state fairs of half-ton humans and conjoined twins when I was a kid in the 1970s (not to mention things in jars at a carnival in St. Louis that should have been given a decent burial).

When Alva Johnston penned the first installment of a three-part profile series titled “Sideshow People,” such attractions could be found across the U.S. and Europe—Coney Island featured “Zip the Pinhead,” who was actually William Henry Johnson (1842–1926), one of six children born to former slaves living in New Jersey. His desperately poor parents agreed to allow P.T. Barnum to display him at a museum and at circus performances billed as a missing link, a “What-Is-It” supposedly caught in Africa.

* * *

Floating and Sinking

As much as New Yorker cartoonists (and E.B. White) liked to take pokes at Chrysler’s futuristic Airflow, there was much to be admired by the innovations the car represented. Unfortunately, the car’s design was too advanced for the buying public, and despite a big manufacturing and sales push by Chrysler the car was shelved by late 1936.

Writing for Time, Dan Neil noted the Airflow’s spectacularly bad timing. “Twenty years later, the car’s many design and engineering innovations — the aerodynamic singlet-style fuselage, steel-spaceframe construction, near 50-50 front-rear weight distribution and light weight—would have been celebrated. As it was, in 1934, the car’s dramatic streamliner styling antagonized Americans on some deep level, almost as if it were designed by Bolsheviks.”

* * *

More From Our Advertisers

Maybe the buying public wasn’t ready for a car with a sloping hood and embedded headlights, but the folks at Cadillac were eager to unveil concepts for the new streamlined La Salle, which retained the familiar bullet headlights so as not to alarm consumers too much…

…and here’s a lovely image from Goodyear…I assume this woman is merely resting in a rumble seat, since this pose would not be possible above 25 mph…

…full-bleed color ads were coming into their own, as demonstrated by this stylish entry from the purveyors of silk garments…

…on the other hand, our well-heeled friends at Ponds stuck with the tried and true copy-heavy approach…here they offer the flawless features of Anne Gould (1913–1962), granddaughter of Gilded Age robber baron Jay Gould…

…R.J. Reynolds continued their campaign to convince us that Camels bring success to the average Joe and the champion athlete…

…the makers of Old Gold opted for the super creepy approach, asking entertainer Jimmy Durante to shove a pack of smokes into the face of what appears to be a teenager…

…here’s another ad from World Peaceways, reminding us of the futility of war…

…speaking of futility, you could visit the USSR, which doubtless took great pains to steer tourists away from mass starvation in Ukraine and mass executions of Stalin’s many “enemies”…

…while folks in the USSR were worshiping Lenin and Stalin, Americans were rightly transfixed by the miracle of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes…a producer of industrial and advertising films, Castle Films would become a subsidiary of Universal and would go on to make a line of science-fiction and horror films including The Wolf Man, The Mummy, and Creature from the Black Lagoon.

…on to our cartoons, Alain took on the recent MoMA exhibition of “Machine Art”…

…and speaking of machine art, George Price was to latest cartoonist to take a crack at the Airflow…

…James Thurber offered this bit of spot art for the opening pages…

…and returned to a somber scene on the battlefield of the sexes…

Next Time: Model Citizens…